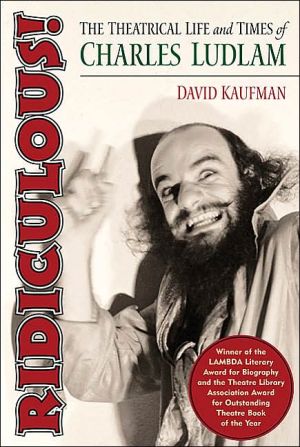

Ridiculous!: The Theatrical Life and Times of Charles Ludlam

(Applause Books). From his first unscripted appearance on an Off-Broadway stage in the revolutionary 1960s to the frontpage news of his death from AIDS in 1987 at age 44, Charles Ludlam embodied and helped to engender the upheavals of his time. The astonishing life and legacy of this force to be reckoned with are at last revealed in RIDICULOUS! , a literary biography of an American comic genius. After founding the Ridiculous Theatrical Company in 1967, Ludlam sustained an ever-shifting troupe...

Search in google:

This is a paperbound reprint of a 2002 book. A former theater critic for the New York Daily News, Kaufman has been covering theater in New York for some 20 years, and is a long-time contributor to The Nation, the Village Voice, and The New York Times. Here he gives an account of the life of Charles Ludlam (1946-1987), a prominent figure in the theater avant-garde, a pioneer of drag performance, and founder of The Ridiculous Theatrical Company (1967), whose work has influenced such performers as Bette Midler and the original cast of Saturday Night Live. Kaufman spent some ten years researching the book and interviewing key people in Ludlam's life and career. Illustrated with b&w photos. Annotation ©2004 Book News, Inc., Portland, ORNew York Times - Mel GussowMr. Ludlam and company are often larger—and funnier—than life. As entertainers, they have brightened more evenings with their jocularity and their iconoclasm than any other theatrical troupe of their longevity.

RIDICULOUS!\ THE THEATRICAL LIFE AND TIMES OF CHARLES LUDLAM \ \ By DAVID KAUFMAN \ APPLAUSE THEATRE & CINEMA BOOKS\ Copyright © 2002 David Kaufman\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 1557835888 \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ SUBURBAN REBEL \ Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made.\ - Immanuel Kant\ I feel appreciated, although I don't think anyone can ever love me enough.\ - Charles Ludlam\ "If Jack Kerouac had to live around here, no wonder he went 'on the road'," Charles Ludlam told his younger brother, Donald, about their Long Island home in Greenlawn, New York. Charles's acerbic allusion to Kerouac had far more resonance than he intended. Like that literary pioneer of the previous generation, Ludlam would always remain close to his suburban home and to his mother, no matter where he roamed or how far he believed he and his art had left them behind.\ Ludlam and Long Island grew up together, part of the suburban experiment that swept across America in the sprawling boom following World War II. The potato fields of Nassau and Suffolk Counties were converted into plots where small-frame houses sprouted like mushrooms; garages became mandatory to accommodate the cars that were suddenly requirements for domestic life. Long before shopping malls became as familiar an American phenomenon as television, commercial-strip shopping centers began cropping up alongthe roads that connected these new communities to the larger highways leading to New York City and the rest of the country. People who had grown up cramped in cities suddenly had the opportunity to establish themselves in places that promised them roots and the freedom to move, as well as a newfound security. The fact that the Ludlams, like millions of others in suburban households, customarily left both their house and car unlocked recalls a time when risk seemed to have been removed from domestic life. Sociologists and other commentators would come to renounce the sentimental deceptions of suburban life as perpetrated by 1950s TV fare like "Father Knows Best" and the "Donna Reed Show"; but the ideals represented by those shows reflected real desires for community, safety, and normality in a world everyone knew could be blasted into atoms at any moment.\ Within this environment of heightened and self-conscious conformity, Charles Ludlam was viewed as an oddball by his peers. In terms of the cultural rebel Ludlam would become, it seems telling that Robert Mapplethorpe-the bad-boy photographer who also upended cultural values later in life-was born in Floral Park in 1946, only three years after Ludlam was born in the same community. As absolutely distinct as their artistic paths would prove to be, Ludlam and Mapplethorpe both grew up to be gay "outlaws" with a particular penchant for standing sexual mores on end.\ No matter how far he would depart from the all-American suburban standards that circumscribed his formative years, Ludlam kept coming home all his life. Always the dutiful son, he frequently made time in his increasingly hectic schedule to return to Long Island for the holidays, as well as for the birthdays, weddings, graduations, and funerals that tend to summon adult children home. His mother claimed that Ludlam never failed to spend Christmas with the family, and he missed only the occasional Thanksgiving dinner when he was touring or otherwise engaged. Though he kept from his parents certain aspects of his life as he became a prominent figure in New York's gay subculture, Ludlam remained close to his mother Marjorie, whose indomitable strength, feisty spirit, and assertive manner he inherited. His relationship with his father, however, would always be problematic, even if Ludlam incorporated Joseph's sense of irony and volatile wit in his own approach to life. Charles Ludlam, master of the mercurial and ephemeral stage, first learned about performance within the dramatic construct of his own family.\ * * *\ Marjorie Ludlam was the youngest of five surviving children. She was born in East Northport, Long Island, in 1913. Her father, Louis Braun, came at the age of fourteen to the United States from Baden-Baden-a popular resort town in the Schwarzwald or Black Forest region of southern Germany-to become a Lutheran minister at a seminary in Georgia. He quickly dropped out of school and became a gardener instead. Marjorie's mother, Bridget Lynch, was an Irish immigrant distantly related to the Bourne family of the Singer sewing dynasty. They sponsored her move to the States in the mid-1890s, when she was about twenty, to become a governess for their children. Bridget shuttled with the Bournes between their posh apartment in the Dakota on the Upper West Side of Manhattan to their mansion in White Plains, as well as to Oakdale, Long Island, where they had yet another estate, which later became La Salle Academy. It was here that Bridget met Louis the resident gardener, and by the turn of the century, they were married.\ Louis and Bridget moved to Brooklyn to raise a family of their own. He opened a landscaping business called Braun's Greenhouses in Flatbush, on Canarsie Avenue, across from Holy Cross Cemetery. By the time Marjorie was born, Louis had sold the Brooklyn operation and opened a larger chain of greenhouses out on Long Island, in Greenlawn. According to Marjorie, when Louis died of throat cancer in 1921, "Mother destroyed everything in a fit of passion. She tore up her marriage certificate and every picture of Father." With a maternal grandmother who acted out her rage in so highly charged a fashion, it would appear as if Charles inherited his knack for the theatrical from his mother's side of the family.\ Bridget sold the greenhouse business only to die a year after Louis, of complications from multiple sclerosis, forcing the Braun brood to fend for themselves. The eldest sister, Florence, was already working as a bookkeeper at a lumberyard in Huntington, and May, the next oldest, was employed as a teller at the National City Bank in Manhattan. Charles and Louis, the middle siblings, eventually went to live with Bridget's brother in Brookline, Massachusetts, where they became, respectively, a florist and a factory worker. While her sisters were at work, the nine-year-old Marjorie was frequently left home alone, and thrust into a premature adulthood. By the middle of the Depression, she was attending Drake's Business College in New York and taking odd jobs to supplement her siblings' income.\ The girl had grit and strength from an early age. When Bridget's health was deteriorating, an officer from the National City Bank made a house call, ostensibly to pay her respects to her employee's mother, but more likely to confirm the validity of May's extended leave of absence. It was Marjorie who gave the visitor tea. When she was thanked for the beverage, the ten-year-old hostess sassily replied, "You don't know anything! You should be thanking me for my hospitality instead of for the tea."\ Charles Ludlam's father, Joseph William Ludlam, was born in 1900 in Long Island's Oyster Bay, with solid Yankee roots he liked to boast about: Joseph's father Charles, also from Oyster Bay, claimed to be a descendent from a passenger on the Mayflower. His mother, Louise McKee, was a Catholic from Syosset. Since a rebellion against the Catholic Church and all that it stood for figured prominently in Charles Ludlam's later life and work, it's intriguing to note that both sets of his grandparents had crossed over the dictates of their respective faiths. His Protestant grandfathers had each married a Catholic a century ago, when it was highly unusual-if not exactly daring-to do so.\ Joseph's father ran a livery stable in Oyster Bay until it burned down, after which he became a bartender and worked on highway construction-among other manual labor jobs he could secure over the years. Joseph was the first of four surviving children. His sister Anne grew up to work for the Long Island Lighting Co. His brother-yet another Charles, but nicknamed "Buster"-worked in a pharmacy. His sister Adeline, the youngest, became a legal secretary.\ By the time Joseph Ludlam met Marjorie Braun in 1940, he was already a middle-aged man working as a plasterer in the summers and as a truck maintenance man for an oil company in the winters. His first wife, Mary, had died two years before of kidney disease. Joseph was compelled to replace Mary as quickly as possible with someone who could help look after his adolescent son, also named Joseph.\ The twenty-six-year-old Marjorie was thirteen years younger than Joseph and still living in Greenlawn with her sisters when she met her husband-to-be. Her brother Louis had married by then, and he eventually opened a greenhouse in East Northport, which would long remain in the family. The prim and proper, lace-curtain Irish sisters Florence and May were slated to be spinsters.\ Marjorie had dated a number of men, but never cared for any in particular until she met Joseph. They were introduced by a neighbor of Marjorie's who worked for Joseph's supervisor at the oil company. Their first date consisted of a dinner at a German restaurant in Mineola. Joseph's looks appealed less to Marjorie than his good nature and his youthful manner, which seemed to defy his age. After a year's courtship, they were married in August of 1941, at St. Phillip Neri Church in Northport.\ With Joseph's adolescent son providing a ready-made family for the young bride, the Ludlams moved to a two-bedroom apartment above a drugstore in New Hyde Park, on the Jericho Turnpike. Shortly after Joseph left for work on the morning of April 12, 1943 -or sixteen months after they were married-the pregnant Marjorie went into labor. Since the Ludlams had no telephone, Marjorie alerted the owner of the drugstore downstairs, and he in turn notified a neighbor who called Joseph to fetch Marjorie and take her to the hospital. After eight hours of labor, Charles Braun Ludlam was born that night in the Floral Park Sanatorium, which later became a gas station.\ According to Marjorie, Joseph Ludlam was jealous of Charles from the moment he was born. Marjorie, for her part, poured most, if not all, of her love and considerable energies into raising Charles. Though Marjorie had already acted as a stepmother, she fell into a familiar pattern that often occurs when a husband and wife redefine themselves as a father and mother, creating a triangular relationship that hinges on their firstborn. In the process, she withdrew her affection from her husband, setting up a resentment of father towards son that became increasingly brutal over the years.\ Throughout Ludlam's life and career, his father would be severely disapproving of just about everything his son did, while his mother would support and nurture his efforts. In a three-page autobiographical sketch he wrote later in life, Ludlam described how his mother "used to cry in the dark, which I found very painful. Often I cried too, in sympathy with her." On a more positive note, Ludlam would recall with fondness the stuffed Panda bear ("bigger than myself") that his father gave him. Charles named him Oscar and took particular delight in the bell attached to one of his ears.\ Since Joseph Ludlam, Jr. was still living with his father and stepmother when his half brother was born, Charles's crib was stationed in his parents' bedroom. Joseph Jr. joined the armed services shortly thereafter; when he was discharged and returned to the apartment in New Hyde Park, Charles was only three, and Marjorie resented Joseph Jr.'s tendency to stay out late at night and sleep during the day. It became incumbent on her to take Charles out every morning to avoid disturbing the "retired soldier."\ Since the Jericho Turnpike was already a well-traveled thoroughfare at the time, Marjotie wouldn't let Charles out of the apartment alone before he went to kindergarten. Without any playmates, Charles invented one of his own, whom he called Willie. Between the ages of three and four, Charles frequently conferred aloud with Willie over how they should play, staging battles with toy soldiers and the like. Charles's attachment to Willie riled Joseph whenever he observed it, and eventually the stern father exploded, insisting that Marjorie forbid such fantasy-like behavior. If Willie was one of the first manifestations of Ludlam's highly charged imagination, it is extremely revealing that Joseph did what he could to suppress his son's creative nature even at this formative stage.\ Ludlam would later recount to Steven Samuels-manager of the Ridiculous for the last seven years of Ludlam's life, as well as the future editor of Ludlam's plays and prose-how one day, when he was around six or seven, his father caught him staring at himself in the mirror in what seemed to be an intensely self-admiring fashion. Joseph slapped him and said, "Don't you ever let me catch you looking at yourself in the mirror that way again!" Charles's relationship with his father was difficult from the start, with Joseph ever on guard to suppress any signs of unmanliness. Some years later, Ludlam was deeply hurt when he offered to help uproot a tree in the yard and Joseph replied, "It takes a real man to do this, and you'll never be one."\ Countering such harsh and dismissive treatment was the loving attention Charles received from his mother and his two maiden aunts. Florence and May doted on Charles, the child they had never had, who returned their affection in kind. In fact, with little disguised envy, Marjorie claimed that whenever the adult Charles was on tour, "He wrote more to my sister May than he did to me"-mostly picture postcards of the wish-you-were-here variety. May was also Charles's godmother.\ The unconditional love he received from his mother and her two sisters induced the future star of Off Broadway to crave and expect adoration from the world at large for the rest of his life. His father's constant rejection, on the other hand, produced a void that Ludlam would spend his life trying to fill-which was, perhaps, the most crucial driving force for his art.\ Eventually, Ludlam would bend gender rules in revolutionary ways, and the seeds for those future achievements were sown in New Hyde Park, with the three women for whom he could do no wrong and the one man for whom he could do no right. Re-seeking on a larger scale the approval of these four critical figures from his youth, the adult Ludlam would inevitably astonish the world with his brilliance.\ Though Ludlam would later claim he learned how to read from comic books, when Marjorie wasn't taking her young child for walks or on shopping expeditions, she read to him constantly. He obliged her with his curiosity and his omnivorous appetite for information. Before he went to kindergarten, Marjorie even regularly read dictionary entries to Charles.\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from RIDICULOUS! by DAVID KAUFMAN Copyright © 2002 by David Kaufman\ Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. \ \

AcknowledgementsVIntroduction: A Lifetime to ExplainIX1Suburban Rebel12The Whole World His Stage193Flaming Creatures474Glitter and Be Gay635With the Force from My Emerald Eye916A Well-Made Play1137In the Forbidden City1538The Ultimate Masochism1859Caprice Itself22310A Talent Like This26711Secret Lives31712Ridiculous Diva35113One for the Ages38314Every Day a Little Death41315Toodle-oo, Marguerite!445Notes463Index475

\ Mel GussowMr. Ludlam and company are often larger—and funnier—than life. As entertainers, they have brightened more evenings with their jocularity and their iconoclasm than any other theatrical troupe of their longevity. \ — New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Frank RichCharles Ludlam's imagination unfurls as if by magic to fill up the tiny house on Sheridan Square and fold everyone on both sides of the footlights into its generous embrace. \ — New York Times\ \ \ NelsenLaurence Olivier? Bah. Gielgud, Scofield, Brando and the rest of the so-called elite bag? Twaddle. The most versatile actor in the Western world is a man named Charles Ludlam. \ — New York Daily News\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyFounder of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company and winner of theater awards and accolades, playwright/actor/director Ludlam epitomized off-Broadway theater with all its edginess, verve and camp. Ludlam, who died from AIDS in 1987 at age 44, founded his company at 23, was profiled in the New Yorker at 33 and wrote scores of plays before his death. The acting pioneer careened like a juggernaut through the theater world, invoking adoration, acclaim and ire. Openly gay before it was acceptable, Ludlam remained a contradiction: his plays addressed sexual taboos, and Ludlam himself often acted in drag; yet while touring in San Francisco, his dismissive comments about the gay community raised protests, and he kept his illness secret until his death. With devotion, depth and dishiness, critic Kaufman has turned a 1989 Interview article into a decade-long love affair with his subject. The resultant chronology of Ludlam's life from humble Long Island birth to premature death reads like backstage gossip. Fanatically detailed-with over 150 interviews with Ludlam's friends, family, lovers and colleagues; excerpts from his plays, letters and journals; and commentary from critics-the book portrays not merely the man but his era, explicating Ludlam as more than a product of the 1960s' revolutionary sexuality, politics and art: a shaper of attitudes and ideas sexual, theatrical and artistic. Kaufman's assiduously researched work is at times heavy going, but will surely hold theatergoers' interest. Photos. (Nov.) Forecast: The dearth of information on the iconic Ludlam, author interviews, bookstore readings and promotions and interviews in major gay publications should make this popular among theater aficionados as well as gay history buffs. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn 1967, Ludlam founded the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, famous for its over-the-top productions filled with gender-bending roles, sex, and drug use. Drawing on more than ten years of research (including interviews with Ridiculous stalwarts and Ludlam's cohorts and ex-lovers), Kaufman, a veteran New York theater journalist, describes this influential playwright and actor's flamboyant life and work in riveting fashion. Ludlam's odd, strict, Catholic household and childhood, the creation and success of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, and his death from AIDS in 1987 are all well rendered. Some of the best portions feature engrossing letters that Ludlam wrote to intimates, balanced by their own comments about him. Kaufman's book complements several other existing works on Ludlam and his company, including Rick Roemer's Charles Ludlam and the Ridiculous Theatrical Company: Critical Analyses of 29 Plays and Ludlam and Steven Samuels's Ridiculous Theatre: Scourge of Human Folly; The Essays and Opinions of Charles Ludlam. Highly recommended for theater and communications libraries.-David M. Lisa, Wayne P.L., NJ Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \