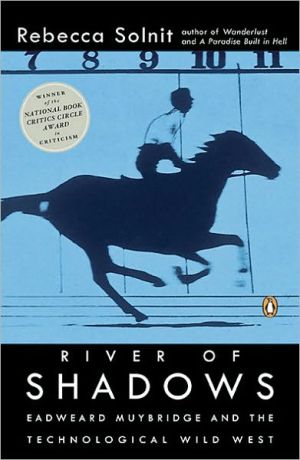

River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West

The world as we know it today began in California in the late 1800s, and Eadweard Muybridge had a lot to do with it. This striking assertion is at the heart of Rebecca Solnit’s new book, which weaves together biography, history, and fascinating insights into art and technology to create a boldly original portrait of America on the threshold of modernity. The story of Muybridge—who in 1872 succeeded in capturing high-speed motion photographically—becomes a lens for a larger story about the...

Search in google:

Writer Rebecca Solnit offers an elegantly written, insightful discussion of the 19th-century technological, artistic, and social transformation of time and space, told through the life of photographer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), whose fine photographs of the American West still astonish, and whose mastery for the first time of high-speed motion photography made movies possible. Annotation (c)2003 Book News, Inc., Portland, ORThe Village VoiceShadows could be a biography, but interspersed between the Muybridge sections is an argument about how capital transformed not only the American West, but the entire fabric of the modern world, from a place where place mattered to an environment without space or time. It is the measure of Solnit's graceful, thoughtful book that she finds in cinema a "breach in the wall between the past and the present" where machines and desires are reconciled.

The Annihilation of Time and Space * 1The Man with the Cloudy Skies * 25Lessons of the Golden Spike * 55Standing on the Brink * 75Lost River * 101A Day in the Life, Two Deaths, More Photographs * 125Skinning the City * 153Stopping Time * 177The Artist in Motion and at Rest * 207From the Center of the World to the Final Frontier * 239Chronology 261Notes 271Acknowledgments 295Photograph Credits 297Index 299

\ The Village VoiceShadows could be a biography, but interspersed between the Muybridge sections is an argument about how capital transformed not only the American West, but the entire fabric of the modern world, from a place where place mattered to an environment without space or time. It is the measure of Solnit's graceful, thoughtful book that she finds in cinema a "breach in the wall between the past and the present" where machines and desires are reconciled.\ \ \ \ \ The Los Angeles TimesRebecca Solnit's River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West is a perfect example of a subject waiting — in this case for almost a century and a half — for the appropriate writer to come along to unlock its concealed meaning and unexpected relevance. The subject is Eadweard Muybridge the photographer and Eadweard Muybridge the phenomenon, and together they have brought out in Solnit a book that is so spirited and free-ranging, so Western in its unfettered questing curiosity, that its genre is not easy to define. — Michael Frank\ \ \ The New York TimesThat's about all there is to the story, and lucky for us: because if Muybridge had had anything like an eventful life, Rebecca Solnit might have had to write something like a standard biography. Instead, we have this vastly more valuable book, River of Shadows, a brilliant essay on Muybridge and all he begat. It is, all at once and in no particular order, a brief summation of a man's life, a meditation on time, image and motion, a history of the American West as a fount of technological innovation and perceptual change, and a beautiful piece of prose. — Jim Lewis\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn the 1870s, at a racetrack built by railroad baron Leland Stanford, Eadweard Muybridge invented high-speed photography. With his camera, he cut time into fractions of a second and laid it out in slices. Never before had human eyes seen a trotting horse distinctly, and the photographs astounded horsemen and artists, especially when Muybridge set the film in motion and the horse reeled fluidly across the screen. Today it is difficult to understand the pictures' impact, but 2001 NBCC finalist Solnit (As Eve Said to the Serpent) vividly recreates the wonder that greeted those primitive movies. Although she points her lens at Muybridge, her true subject is the perceptual revolution of the 19th century when the railroad, the telegraph and the camera transformed the experience of space and time. English-born Muybridge launched his career in 1867 with scenes of Yosemite and San Francisco. He soon began the experiments with "instantaneous" photography that led to the famous motion studies. Except for its most dramatic moments-the murder of his wife's lover, a suit against Stanford-the photographer's life remains obscure. Insistent on writing a biography nonetheless, Solnit pads the book with an account of workers' strikes, an aside on Victorian geology and other irrelevant details. Left to speculate about Muybridge's inspirations, she attributes much to a head injury resulting from a stagecoach accident. Her claims about Stanford and Muybridge as the progenitors of Silicon Valley and Hollywood are equally unsubstantiated. If the book fails as biography, however, it succeeds as a critical essay on Muybridge's art and a reflection on the meaning of space and time. B&w photos. (Jan.) Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn 1872, Eadweard Muybridge was commissioned to photograph a trotting horse to settle a bet as to whether its four hooves could be off the ground at the same time. This seemingly trivial question sparked his interest in capturing animal locomotion-and led to his fathering modern motion picture technology. Depicting her subject as "a damaged man, an isolated one, and apparently one who suffered deeply," Solnit (Wanderlust) describes his work in lensing panoramic Western landscapes, his post as official photographer of the government's war against the Modoc Indians, and the influence of his "zoopraxiscope," a set of spinning images that simulated motion and laid the foundations of modern cinema. More than a biography, this is a social history of the 19th century, when innovations like photography, motion pictures, the telegraph, and the transcontinental railroad attempted to capture and conquer space and time. Although Solnit devotes much space to Muybridge's personal history, including his murdering his wife's lover, the narrative does not always bring Muybridge to life, nor does it always mesh comfortably with the larger social history. The writing is skillful and provocative but marred by too many digressions. A supplementary purchase on motion picture technology and photography for large public and academic libraries. [In June, Oxford University Press will publish Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Movement, an exhibition catalog.-Ed.]-Stephen Rees, Levittown Regional Lib., PA Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsGracefully written, thoroughly well-considered life of the 19th-century California immigrant whose strange experiments in photography yielded both Hollywood and Silicon Valley. \ That’s a tall claim, but Solnit (Wanderlust, 2000, etc.) defends it capably, if sometimes obliquely. In the way of many transplants to California, English-born Eadweard Muybridge (1830-94) reinvented himself a few times--changing his name, for example, from the slightly less exotic Edward James Muggeridge--before settling down in San Francisco in 1855. Within a few years, Solnit remarks, he "became a father, a murderer, and a widower, invented a clock, patented two photographic innovations, [and] achieved international renown as an artist and a scientist." He also attracted a sympathetic ally in railroad baron Leland Stanford (1824-93), who commissioned him to photograph a racehorse on the run to settle a bet as to whether a trotter ever has all four feet off the ground at the same time, thereby helping Muybridge become one of the most famous photographers of the day. One of many motion studies Muybridge conducted, the resulting sequence of photographs inspired other students of photography to press forward with the "zootropic" inventions that would soon thereafter yield the moving picture and thus Hollywood. Out of Stanford’s belief in bankrolling experimenters such as Muybridge, Solnit writes, came Stanford University, seedbed of Silicon Valley. Together, the entertainment and high-tech industries "changed the world . . . from a world of places and materials to a world of representations and information, a world of vastly greater reach and less solid grounding"--again, it seems, a perfectly California thing todo. Solnit does a fine job of placing Muybridge’s and Stanford’s contributions in the context of the other technological changes sweeping the world at the time, and of describing the role of photography in shaping late Victorians’ worldview and culture. She writes with considerable flair, her smart commentary illuminating the dozens of images that accompany her text.\ A welcome contribution to the literature of photography and of California.\ \ \