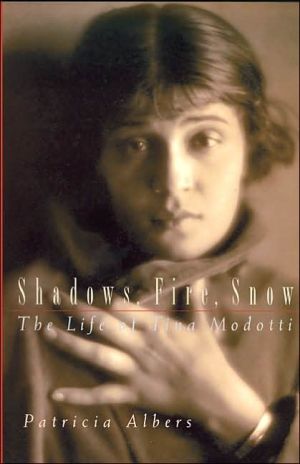

Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti

Ten years of research and the discovery of long-forgotten letters and photos enabled Patricia Albers to bring new recognition to this talented, intelligent, and independent photographer whose life embodied the cultural and political values of many artists of the post-World War I generation.

Search in google:

55 b/w photographsTen years of research and the discovery of long-forgotten letters and photos enabled Patricia Albers to bring new recognition to this talented, intelligent, and independent photographer whose life embodied the cultural and political values of many artists of the post-World War I generation. Author Biography:Patricia Albers is a writer and independent curator who has also worked as a museum administrator. In 1996 she organized the exhibition Dear Vocio:Photographs by Tina Modotti. And in 2000 she curated Tina Modotti and the Mexican Renaissance, which traveled in Europe.Gail JaitlinTina Modotti is perhaps best known as the lover and model of photographer Edward Weston, but she was also an actress, model, and political activist. An accomplished photographer in her own right, Modotti was responsible for a number of striking and well-regarded photographs, although she worked in this field for only 7 of her 43 years. Figuring out exactly who Modotti was, or who she pictured herself to be, is the aim of Patricia Albers's new biography, Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti. Born in Italy in 1896, Modotti endured a childhood of poverty and displacement. Moving from town to town while her father looked for work, Tina dropped out of school at age 11 to go to work in a silk mill. She finally joined her father in San Francisco when she was 17 (he brought over his children and wife one or two at a time, as he could afford to), but her early experiences helped inform her later political sensibilities and her photographs of Mexican workers. In San Francisco, she worked for a short time as a seamstress before becoming involved with local Italian-language drama troupes. She was a fixture in San Francisco's circle of Italian bohemians and artists and soon became well known as an actress and artist's model. A dark-haired beauty with full lips and smoky eyes, Tina had no difficulty meeting men. Her first true love was Roubaix de l'Abrie Richie (Robo, for short), a debonair charmer who dabbled in painting and writing, and with whom she moved to Los Angeles (where she had a brief career as a silent film actress) and then to Mexico City. Her second love was Edward Weston, the photographer, for whom she modeled in L.A. and with whom she took up residence in Mexico City after Robo's tragic early death from smallpox. It was not until she was 27 that Modotti started taking photographs, and even then it was in the long, dark shadow of Weston. A well-known photographer by then, Weston was interested in breaking with previous formal tradition and exploring composition and light. He and Modotti set up a studio together, where they took portraits for money while pursuing their more artistic interests. In the 1920s, Mexico City was an exciting place to be. The revolution had just ended, and a cultural revolution was taking place. The new minister of education was distributing freshly printed volumes of the works of Homer and Tolstoy to the masses; muralists had been hired to paint enormous public paintings of traditional Mexican subjects. As Albers writes, "Intellectuals who had once looked to Europe for cultural revelation now turned their backs upon the old continent, embracing instead the genius of peasants and indigenous peoples.... [Lured by] vibrancy and ferment, anticipating inspiration, and titillated by skirmishes between marauding guerilla bands...foreign pilgrims...board[ed] trains and boats bound for Mexico." It was against this backdrop that Modotti started her career in photography. At first experimenting only with still lifes (especially flowers), Modotti was eventually able to purchase a Graflex camera, which allowed her to dispense with a tripod and take to the streets. Her most vibrant pictures are those of Mexican workers and peasants. It was here that she found her true voice and was able to break away from Weston's influence. Her political beliefs, which informed so much of her photography, were ultimately to blame for cutting short her professional career (and perhaps her life). She became a Communist upon first moving to Mexico, in part because of the political fervor among her social milieu but also as a response to fascism and Mussolini, who she believed was destroying her precious homeland. After her relationship with Weston ended, Modotti became involved with Jose Mella, a Cuban revolutionary who was assassinated as he walked down the street with Modotti. Harassed by officials and suspected of spying, she was eventually deported to Berlin in 1930 and spent a peripatetic decade traveling around Europe as a revolutionary. Although she took some more pictures, she never found another subject that intrigued her as much as the Mexican people; eventually, she gave photography up entirely. When she died in Mexico at the age of 43, it was under mysterious circumstances. She'd been back in the country less than a year. In this evocative portrait, Patricia Albers does a wonderful job invoking the sights, sounds, and smells of life in the bohemian circle of Mexico City circa 1925, when the very air seemed infused with the excitement and ardor that surrounded activists and artists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. But Modotti remains the primary focus of the book, and a fascinating subject she is. To her credit, Albers focuses on Modotti's artistic endeavors as well as on her romantic involvements, which is not an easy task. The artist's romantic life threatened always to overshadow her photography, and the one source of insight into Modotti's mind, her personal journal, was burned, along with many of her letters. Albers's portrait is, then, a welcome introduction to a woman who has remained too long in the shadows. --Gail Jaitin

Shadows, Fire, Snow\ The Life of Tina Modotti \ \ By Patricia Albers \ University of California Press\ Copyright © 2002 Patricia Albers\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 9780520235144 \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Friuli and Austria (1896-1913)\ \ \ By nine o'clock, Mexico City's Artes Street lies bathed in moonlight and nearly silent. Even a commotion of departures from the shabby little apartment house at number 46 is dying down. It is January 5, 1942, the eve of the Day of the Magi, one last flurry of holiday-making before the onset of what looks to be another hardscrabble and dreary year.\ All evening, the war has been on the lips of party guests, who hold forth in German-, Italian-, and Castilian-accented Spanish. Mostly seasoned European Communists exiled by fascism, they exhale streams of words with their long gray curls of cigarette smoke. Caught between rasping laughter and the low moan of the phonograph, voices wrangle over the fate of Hitler's armies, ensnared by the Russian winter, and the tactics of the United States, scrambling to defend its Pacific outposts after Pearl Harbor. In one corner, several women thresh out final preparations for the next afternoon's fiesta where Spanish refugee children will squeal with delight at homemade toys, gifts from the Magi. As the bubbly party babble eases,departing guests pull the door shut with a spate of hasta mañanas.\ Lights dim in the small flat, modernist and arty, as befits the home of a weaver and a former Bauhaus architect. Four guests, intimate friends, settle in with their hosts for a cozy chat. One couple is Spanish, a distinguished-looking former general and a genial relief worker. The others are Italian. The man, a paunchy, bull-necked sometime journalist from Trieste, dominates the conversation, but his tiny, less voluble companion, María, is easily the more arresting presence.\ María had been one of the legendary beauties of her time. Set under quizzically arching brows, her luminescent velvety brown eyes are still stunning. Her teeth, however, are yellowed from years of smoking. Her skin appears mottled and parchmenty, and her mouth is drawn.\ As always, she has groomed herself carefully and rather severely. Parted in the middle and pulled to the sides of a low forehead, her dark hair, dulled with gray, is twisted back into a complicated chignon. She wears no jewelry. Dressed in a black suit and white blouse, impeccably tailored, if slightly frayed, she might be mistaken—at a distance—for a soulful Mexican abuelita, a grandmother perpetually in mourning. Yet she is only forty-five years old.\ Warm and attentive to her companions, she talks and smiles, but the sacred fire that once danced inside her has been squelched. Instead, says a poet friend, so muffled is María, that thinking of her is like "trying to scoop up a handful of mist." Her hush is less an estrangement from the living, however, than strained attention to the low clamoring of the dead. María has loved many who have not survived the savagery of the century. Submerged deeply within her memory are their faces and stories, too complex and painful to discuss. In years gone by, she was eager to talk out important issues. Now she feels less North American, more Latin, more austere.\ Chitchat bounces from Soviet general Simeone Tomoshenko to anti-tank trenches to Dimitri Shostakovich's Quintet op. 57. Pleading a late-night editorial meeting, the journalist takes his leave. Someone begins fantasizing about a postwar journey to Madrid, Genoa, and María's hometown of Udine, Italy. There would be feasts of panettone and Chianti, and she would roam the old streets for the first time in twenty-nine years.\ Feeling fatigued and queasy—perhaps from the heavy meal and the wine—María departs after midnight. She is accompanied to the street by a neighbor who stuck his head into the gathering on his way upstairs. As they step onto the pavement and walk two long blocks to Ramón Guzmán Street, María feels a night chill wrapping itself around her. On the busy thoroughfare, an outstretched arm easily stops a cab, whose fare she automatically bargains down from two pesos to one. Stepping up on the running board, she then nestles her wispy body into a corner of the ample backseat.\ "Hasta luego," she murmurs.\ "Hasta luego."\ According to her habit, María gives the driver the name of the General Hospital, a landmark across the street from her apartment. The vehicle rumbles over the uneven pavement of central Mexico City, the light of a full moon quivering and darting among its lugubrious buildings. During the window-rattling ten-minute ride, the only sound from the backseat is a bout of wheezing. After the driver pulls up in front of the hospital, he swivels to collect the fare, only to discover his passenger slumped over. Dashing into the admitting room after she barely responds to his questions, he is instructed to rush her to the Green Cross emergency facility. María's last flickering perceptions are of darkness, solitude, and drift. By the time the cab reaches the hospital, she sprawls lifeless across the smooth cold leather.\ Though many knew her as María Ruíz or María Jiménez, the woman's true name was Tina Modotti. Never a flamboyant personality, she was nonetheless pursued, even after death, by a glaring spotlight of publicity and controversy. Her burial, in a fifth-class tomb, drew many of the grand old warriors of international communism. Meanwhile, Mexico City's modern art gallery readied a retrospective of her photographs, and journalists dredged up yellowing scandal sheets shrieking of romance, violence, deceit, and Tina Modotti. In the obituaries, old rumors mingled with new: Tina died drunk, she had a heart attack, or she was eliminated because she knew too much. "The dramatic circumstances surrounding [her death] measured up to those of her agitated, subterranean and adventurous life," typed one eager reporter. "Bees, shadows, fire, snow," intoned Chilean poet Pablo Neruda in his elegy, "silence and foam combining with steel and wire and pollen...."\ Fittingly, Tina Modotti died en route. Though she reveled in being of a place, a people, a profession, all proved slippery to her touch. No sooner did she plant one foot on firm ground than the earth eroded under the other, leaving her geographically and emotionally homeless. Acknowledging a "tragic conflict between life which continually changes and form which fixes it immutable," she responded by improvising, with all the grace she could muster, a series of remarkable lives.\ In the first, the one that seemed her destiny, Tina Modotti was the flesh and blood of impoverished Italian workers. Not yet two years old when political and economic turbulence cast her family from its homeland, Tina would grow up to cling tenaciously to her Italianness, all the more precious because precarious. Her early childhood was spent in Austria, and when she finally learned Italian, at age nine, she spoke with a faint German accent. Often labeled the "tempestuous Italian" or "bellissima italiana," Tina was barely familiar with the country. Her Italy was no more than one provincial town. "Of Italy," she once wrote, "[I know] only Udine...."\ Tina Modotti's hometown is the capital of the northeasternmost Italian region, officially named Friuli-Venezia Giulia but usually called simply Friuli. Fabled cities lie within easy range—Venice and the mottled neo-classical seaport of Trieste—but Tina's is a modest bourg set on a yawning plain of maize fields, vineyards, and orchards. From the pine-bristling slopes of the Carnic Alps, to the north, a lush carpet of wild hawthorn, clover, and shaggy grasses tumbles down Friuli's village-dotted valleys, running out at the sand-rimmed sea. Drab in winter, then suddenly sodden with alpine runoff, the region turns dazzlingly verdant in spring.\ Friuli might have been nothing more than a bucolic agricultural hinterland had it not the misfortune of a strategic location at the head of the Adriatic. As chaotic as its name implies, Friuli-Venezia Giulia has a history that abounds in annexations, invasions, sieges, and overswarming armies. In ancient times, the Romans imposed a sprawling port city at Aquileia; during the Dark Ages, Central Europe's landlocked suzerains made Friuli's mountain passes their bloodied corridors to the sea. For nearly four centuries, Venetians chiseled the winged lion of San Marco on public buildings as a seal of ownership, never quite secure from raiding Turks. It was ultimately Napoléon who, in 1797, quickstepped in to wrest the territory from Venice, then trade it to the detested Austrians, thus earning for himself an enduring role as a buffoon in Udinese street theater. In 1866, the region was partitioned, with Udine swept into the new nation of Italy. Flush with the patriotism of the risorgimento, the town doted no less upon its legacies of raisin-studded Slovenian pastries, plumed Tyrolean hats, and Venetian-style carnevale.\ By the late 1860s, when it enjoyed a respite from military turmoil, Udine was a conservative textile manufacturing center of nearly 37,000 inhabitants. On Sunday afternoons, townspeople took the air in its charming central piazza, graced with a candy-striped loggia, and wended their way up its castello-crested hill. Udine's prevailing atmosphere was unostentatious and countrified. Errant cobbled or dusty streets strung together the once-medieval burgs of Poscolle, Grazzano, and Cussignacco, behind whose animated commercial districts clotted narrow, shuttered houses. They bore their years gracefully, faded frescoes appearing out of patchy umber, sienna, or saffron facades, and window ledges bright with coquettish tumbles of geraniums. Here and there, stone walls hid neat rows of tomato, pepper, onion, and radicchio, and church bells steadily chimed out the hours of the day. With its gentle light, utterly unlike the hard glint of southern Italy, Udine was cluttered with pleasant corners tempting one to while away the afternoon. Some lingered in its market square cafés, others on footbridges arching canals sputtering with trout. Unlike the grand waterways of Venice, these were narrow, prosaic streams whose reflections danced across the facades of overhanging houses. To their embankments, womenfolk eternally lugged big stiff-handled baskets of laundry, bending low at scrubbing and rinsing as tongues wagged with gossip.\ Among the washerwomen at the old moat near Gemona Gate was Tina Modotti's paternal grandmother, the only grandparent the girl ever knew. A flinty, rather shriveled matron by the age of thirty, her hair stuck into a tight knot, Domenica Bertoni Saltarini Modotti was, more often than not, heavy with child. One scarcely noticed, however, for she rustled about in layered Friulian peasant dress—an aproned ankle-length dirndl, fringed capelet, and head scarf tied low behind the neck—fashioned from dark patterned fabrics.\ Like Tina's parentage on all sides, the Bertonis had been entrenched in Friuli for as long as anyone could remember. Born in the mill town of Molin Nuovo, Domenica had managed to snare for herself a fine Udinese husband. The widower Domenico Saltarini Modotti, a parishioner at the Church of Redentore, knew how to read and write, and, more consequentially, owned a small acreage just outside town. As a Friulian peasant, he would have been hardworking, frugal, and undemonstrative by temperament, judicious in his words and actions.\ Domenico's dual loyalties to Italy and Friuli were mirrored by his composite surname. The Italianized plural of Modotto, Modotti was a name common enough that the family distinguished itself by retaining the Friulian appellation Saltarini. The reference was probably to ancestors once inhabiting the hamlet of Salt or employed as forest guards, saltarîn in the Friulian language. Both Domenico and Domenica had been subjects of Austrian emperor Francis Joseph I and now owed allegiance to Italy's king, but their deeper identification lay close to home. Between themselves, they spoke Friulian—very like Switzerland's Romansh—and this regional language, less lyrical and more raucous than Italian, would be Tina Modotti's native tongue.\ With her marriage, Domenica had inherited three children, and from the union with Domenico issued Giuseppe, Francesco, Vittorio Emanuele, Anna, Pietro, Lucia, Angelo, and Andreas Leonardo. As the new generation came of age, the future boded ill, owing to Italy's plunge into severe and prolonged economic depression. The girls set to work on dowries, and the boys, a slapdash education under their belts, briefly took up scythes in their father's fields. But one small tract of land could never be stretched to support the Saltarini Modotti progeny. Andreas Leonardo departed for Gorizia, Giuseppe and Francesco apprenticed as mechanics, and Pietro became a pork butcher.\ Curly-haired, with bright, hard eyes and a soup-strainer mustache, Giuseppe Modotti was a quick-witted, easygoing young man, who showed himself to be thoroughly modern by discarding the name Saltarini. Passionate about opera and endowed with what his daughter Tina described as "a pleasant, jolly voice," he was given to intemperate outbursts of aria. Rarely did he appear without a newspaper, which he could read fluently, though he never felt confident enough to claim that he could write. At twenty, Giuseppe was declared unfit for military service because of severe phlebitis; at twenty-four, he hied himself to the bustling Mediterranean port of Genoa to search for work.\ Larger and more industrialized than Udine, the city opened Giuseppe's eyes to the disjointed welter of disparate factions that was Italian radicalism. One set of quarrels opposed Mikhail Bakunin's anarchist followers—romantic, antireformist, and bent on mangling the bourgeoisie with acts of violence—to adherents of "scientific socialism, loosely based on the tenets of Engels and Marx. From two years in Genoa, Giuseppe carried home a newly sophisticated political awareness, which he channeled to his brothers, some of whom enrolled with him in the nascent Italian Socialist party.\ Agitating for universal male suffrage, Socialists endeavored to coalesce the visceral hostility of Italy's masses into political activism. Giuseppe's circle took a moderate anarcho-syndicalist line, militating for shorter working hours, holidays off, and safer conditions in the mills, but its overarching concern was with advancing class consciousness and the knowledge that the masses were the creators of society's wealth. In the absence of working-class solidarity, Socialists fumed, there was no hope that Udinese laborers could pull off a decent strike, for "the capitalists would be chuckling under their mustaches because they knew they could easily find other workers...."\ Back in Udine, a stint as an orphanage handyman brought Giuseppe to Via Tomadini and twenty-six-year-old Assunta Rosa Catterina Mondini, who lived around the corner. Of the youthful Assunta, we know that she was short and lovely to behold, with narrow, lively eyes and waves of mahogany brown hair. A serious and composed woman, she was also a great talker, who may have made it her business to become acquainted with the good-looking mechanic.\ The Mondinis constituted a veritable guild of clothiers. Assunta's maternal grandmother had been a silk embroiderer. The girl's mother, Adelaide Zuliani, a dressmaker, married Giuseppe Mondini, a hatmaker, and their brood of nine counted several garment makers, three hatmakers, and a cobbler. Needles flying over lengths of linen or silk, Assunta and her sisters expertly whipped out piecework in the small apartment where they all lived on top of one another. Rarely finding enough employment to absorb their industriousness, the Mondinis made ends meet one month at a time. Yet, money or no, to be a Mondini woman, or, like Tina, the daughter of a Mondini, was to be impeccably dressed and to sew like an angel.\ The family inhabited the upper floor of an undistinguished two-story house on Via Pracchiuso. Renters rather than owners, the Mondinis nonetheless felt deeply at home in their neighborhood, called San Valentino, after its tiny church. Fate seemed to confirm their belonging with the birth of Assunta's brother Valentino, on February 14, and Assunta's own birthday on November 25, Saint Catherine's Day, feted since the Middle Ages on the neighborhood green. By the time Giuseppe came courting, however, marriage and emigration were plucking apart the Mondini clan.\ In the spring of 1892, Assunta discovered she was pregnant. The news did not unduly shock or shame her family, for Assunta's eldest brother had been born out of wedlock. A month later, however, his parents had hastened to tie the knot, ostensibly because of the stigma attached to the misbegotten child. Identification papers, even school lists, would otherwise carry the mention "child of unknown father," and epithets on the street were considerably less polite.\ Halfway through Assunta's pregnancy, the Mondinis were stunned by the deaths, probably from infectious disease, of their patriarch, Giuseppe Mondini, and, the very next day, of Assunta's sister Leonzia. With two fewer breadwinners, soon another mouth to feed, and a heightening economic crisis, the family's tattered Via Pracchiuso remains—old Adelaide, three adult children, and a niece—faced a bleak future.\ In her eighth month, Assunta resolved, or at least ameliorated, the situation by marrying Giuseppe Modotti in the grand Basilica delle Grazie. The bride, in mourning, would have had a kind word and gracious smile for each of her guests, while the groom masked with bonhomie his chagrin at being married by a priest. The church was hand in glove with the possessing classes, yet Catholicism permeated Udinese culture, and, Socialist that he was, Giuseppe was also an eminently pragmatic man.\ Unfortunately, we are not privy to relatives' gossip about why Assunta and Giuseppe Modotti chose to plight their troth, nor do we have a single wedding picture to scrutinize. What kept the couple hesitating about marriage, one wonders, until the last weeks before the birth? Did the union have its basis in emotional trauma and obligation? Was theirs, at bottom, a vital relationship invested with passionate love, or was the pair ceding to what seemed an inevitability for burdened, uneducated, struggling folk?\ Given Tina's dismissive attitude toward marriage and the tumult of her relationships with men, it would also be fascinating to know more than we do about the emotional texture and tone of her parents' thirty years of connubial life (interrupted for half that time by Giuseppe's fortune-seeking in the United States). The marriage no doubt saw few stormy scenes but was shot through with strains and misapprehensions. Implicit in her children's frequent references to Assunta as "a saint" and "our blessed mother" may be the thought of Giuseppe's distraction or infidelities. The notion that the relationship was disturbed is borne out by the observation that the couple's six children who reached adulthood lacked the capacity for long-term, stable, intimate bonds. Instead, their affective lives were confused sagas of brief happiness, dashed hopes, squabbles, separations, and divorces.\ Whatever disenchantment the Modottis' marriage held, it was leavened by mutual devotion to their offspring. Tina spoke affectionately of her father, although the two were not well acquainted until the last years of his life, for Giuseppe was inevitably toiling or chasing down another dreary factory job somewhere. But she admired his entrepreneurial spirit and the gutsy way he labeled himself, as circumstances dictated, mechanic, machinist, mechanical engineer, bicycle repairman, inventor, marble cutter, or photographer. He was, she boasted, "a true fighter, an untiring worker," and he never grew sour or taciturn, instead remaining "younger in spirit than [his own sons]—how much I [admire] him always!" She inherited his resourcefulness, his faculty for hard work, and his undying faith in the millennium.\ An old soul, stoic, sweet, and indomitable, Assunta played a larger role in the lives of her children, whom she cosseted and cared for as best she could. Her possibilities constricted from childhood by lack of education and the dreary lot of poor friulane (including those married to Socialists, who typically recognized no specific oppression of women), Assunta displayed inextinguishable selflessness and serenity. Having witnessed her mother's considerable suffering, Tina felt unwavering tenderness toward her. One side of Tina, more pronounced as she grew older, was the very image of Assunta.\ The Modottis' firstborn, Mercedes Margherita, would arrive four weeks after the wedding, and their second, Ernesto Renato (sometimes called Carlo), twenty-two months later. Both births took place in the Mondini home, Giuseppe having disregarded convention by moving in with his bride's kin, rather than the other way around. Picked from neither branch of the family tree, the babies' names were perhaps of their father's invention.\ With the baby born on August 16, 1896, Assunta put her foot down. The newborn's namesakes, all Mondinis, were Assunta herself (the mother), Adelaide (the grandmother), and Luigia (a maternal aunt). The first name also brought to notice the child's Catholic heritage and her birthday's near miss of the August 15 Festival of Our Lady of the Assumption, Assunta in Italian. Probably following the Friulian custom of altering offsprings' names to confound malevolent spirits who would do them harm, the baby's parents used the diminutive, Assuntina, then simply Tina.\ It was five months before they proceeded to christen her. A sweeping glance around the drafty basilica's baptismal font on January 27, 1897, would have revealed, besides more Modottis and Mondinis than anyone could keep straight, a barber named Antonio Bianchi—the baby's godfather—and her two sponsors. One was Assunta's sister Lucia, whom Giuseppe grandiosely listed on the baptismal act as his daughter's governess, and the other a shoemaker named Demetrio Canal. A well-known figure in the history of Udinese radicalism, Canal no doubt had to be coaxed into his role, since he routinely lambasted Catholicism—"that religion"—for its oppression of the working masses.\ Canal was a moving spirit of the Via Cicogna circle, a Socialist fellowship that Giuseppe Modotti attended on Thursday evenings. The group discussed the meanings of radicalism, devised and carried out militant actions, and, briefly, published a weekly called L'Operaio. The paper took to task Udinese bakery owners for forcing youngsters to toil through the night, then deliver bread at dawn, and silk tycoons for levying fines on young workers who paused to rest. For Giuseppe, the struggle against local oligarchs, who wielded power as their God-given right, was no armchair gambit. His three children could look forward to only the briefest of childhoods, with perhaps a year or two of schooling, before wading into decades of dreary factory grind. Marriage to a steady, hardworking man seemed his daughters' brightest hope.\ That spring, Udine plunged into turbulent social unrest fueled by the free-floating anger of jobless workers and hungry peasants pried from the land. Factory employees improvised a round of strikes, repressed with increasing violence. For acts of solidarity with a spinners' walkout, potentially crippling to the vital textile industry, the Via Cicogna circle was banned.\ Under scrutiny by Udinese police and probably unemployed, Giuseppe Modotti bid farewell to the family and joined a rowdy, ragtag caravan of Italian job seekers bound for the southern Austrian province of Carinthia. His train heaved itself over the Alps to the cow town of St. Ruprecht where it disgorged its load of brawn for forests and factories. In a cycle of economic recovery, Carinthia was reaping the benefit of new rail links to convert itself into a regional supplier of heavy construction materials. Employment generally lasted as long as the mild season, and, by November, with winter closing in about the village, most Italians had returned home. Hired for an indoor job, Giuseppe, in contrast, convened the entire family in St. Ruprecht. Then fifteen months old, Tina would call Austria home for the next seven-and-a-half years.\ Tidy and picturesque, St. Ruprecht nestled among low mountains, a kilometer or two from a popular villa-lined lake resort. Sprawling rail yards delimited the hamlet's northern boundary; massive stone-and-wood edifices petered out in pastures to the south. The only thoroughfare sliced the little settlement in half, then continued on to nearby Klagenfurt, the prosperous burgher town of which the village was a workers' ghetto.\ The Modottis were assigned to a dormitory, called Building No. 74, hard by the railroad tracks. Their lodgings provided lumpy straw mattresses, a primitive kitchen without running water, and only a fireplace for heat. Biting cold filtered in around windows and doors, and soot scooted into every cranny. In the evenings, the intermittent, earsplitting roar and screech of trains would drown out distant bursts of beery shouting. Intended for seventy people but meagerly inhabited in winter, their abode would be invaded come spring by a stream of Slovenian and Italian new arrivals as St. Ruprecht's population swelled to three thousand.\ Giuseppe's mechanical skills earned him a good job as a maintenance man for steam-powered equipment at the crate, beam, and building materials mill of magnate Friedrich Brodnig. Meanwhile, Assunta—one eye trailing the trio of little Modottis—knuckled down to housekeeping and piecework for someone such as Anna Pagura, the Italian who sold clothing from her home on the Klagenfurt road.\ Just as the family established itself, tragedy struck. Seized by high fever and convulsions, three-year-old Ernesto suddenly expired, the causes of death listed as tuberculosis and meningoencephalitis (possibly linked to drinking unpasteurized milk). This older brother may have quickly faded from Tina's memory, and even Ernesto's parents had scant opportunity to express their grief, for, by May, Assunta was in the morning-sickness phase of another pregnancy, and Giuseppe was hospitalized for unknown reasons in Budapest, where he was doubtless attending a union meeting for Italian migrant workers.\ Baptized Valentina Maddalena (but called Gioconda), the baby was born after the Modottis had quit St. Ruprecht for the misty hamlet of Ferlach, two hours to the south by creaking horse-drawn carriage. Secluded by the wide Drau River valley and walls of jagged peaks, Ferlach lay under an oppressive winter silence, pierced from time to time by volleys of church bells, ice chunks crashing from the roofs, and the crack of its famous hand-built rifles. The family took rooms in a building shadowed by the church, where Mercedes learned the German Christmas carols she remembered her entire life. As spring stirred, she and little Tina streaked through boggy meadows glorious with wildflowers, their boisterous laughter met with terrifying sternness from leathery-faced, loden-hatted burghers. Italian loggers arrived en masse, and, in the evenings, they kindled up small fires and cooked their polenta outdoors.\ It was southern Austria's bicycling mania that put Giuseppe in Ferlach. Klagenfurt's Grundner & Lemisch bicycle works, renting space from a local arsenal, had engaged him as a mechanic, and family lore has it that he invented a lightweight bamboo mountain bike successfully manufactured by the firm. But something soured, and, some two years later, the Modottis resumed their vagrancy. Tina's third sister, Yolanda Luisa, was born in 1901 in St. Ruprecht's Building No. 105, and, in 1903, Assunta gave birth to Pasquale Benvenuto, called Ben, in Building No. 129.\ At four, Tina was chubby and hoydenish, with brown eyes and dark unruly hair. Dolled up with an intricate embroidered collar, she appears, in the only surviving photograph from her girlhood, most friendly with the camera. Just emerging as a self-aware person heedful of the outside world, Tina experienced a cultural identity subject to constant renegotiation. To Austrians, she was an Italian child, though she spoke scarcely a word of the language. At home, she made herself understood in Friulian, but on jaunts with her mother around the village, conversations were interlarded with Italian, German, and Slovenian. At primary school, Tina would discover that pupils were required to use German and not one word of other languages, on pain of punishment, a policy that so enraged the Slovenian community that it published a long tract of protest. Whatever else Tina's memory retained of the Austrian years, it absorbed foggy, troublesome impressions of nationality, cultural identity, and marginalization, issues that would stack up as significant in her life.\ Ethnicity took on other dimensions in the adult world, where discrimination and festering animosity were taken for granted. Austrian employers pitted the interests of one set of workers against another by locking out strikers and replacing them with newer, cheaper immigrants. Attempting to organize across ethnic lines, Giuseppe Modotti and his cohorts found music in words such as those spoken by a Triestine immigrant before three hundred construction workers at a Klagenfurt rally: "Your friends, your colleagues, are German and Slovenian workers. Your own compatriots, Italians with money, are totally indifferent to your well-being." One of Tina's earliest memories, told to her sister Yolanda, was of a similar gathering, a clamorous May Day parade through the streets of Klagenfurt, where she bounced along on Giuseppe's shoulders as he explained the significance of the hard-won holiday. The story has been singled out and emphasized by those who would make of Tina a working-class heroine, and, while true, it does have the ring of official biography.\ The year she turned nine, Tina's life was transformed by a chain of events beginning with a letter postmarked "Turtle Creek, Penn., U.S.," and signed by Giuseppe's brother Francesco. For thirteen years, Francesco had moved between Italy and the United States, but now he must have discerned particularly bright opportunity in the steel mills and mining zones of western Pennsylvania. Returning to Udine, where he deposited his family and settled his affairs, Giuseppe caught a train in the direction of Le Havre, France, to embark for New York and then join Francesco. At forty-two, Giuseppe would make a fresh start, summoning his offspring one by one as he amassed enough savings for their passages. Two months after his departure, the Modottis' last child, Giuseppe Pietro Maria, called Beppo, came into the world.\ The family had settled back into Udine's San Valentino district, renting a room or two in a house where the children had the run of a cobbled courtyard and its clutter of brooms, birdcages, potted plants, and stray cats. The siblings lived in frenzied expectation of tidings from Giuseppe, but letters rarely reached them, money almost never, and he sank from the little ones' memories. "For long periods of many months, we had no news of him, and he didn't send money because of lack of work," Tina remembered. "That meant that we practically lived on charity." Despite helping hands from the Modotti and Mondini clans, the family's fortunes deteriorated rapidly. In the little pool of light around a coal stove and a candle, they dined frugally on the eternal polenta of Friuli's poor, smothered with vegetables and cheese when times were good and thinned with extra water when they were bad. Afterward, chattering with cold, the children would pile into bed together, snuggling to keep warm.\ "In Udine," a friend paraphrased Tina's anecdote decades later, "there was a fine house, and, something strange, this man's daughter, an aristocrat's daughter, invited her for dinner and, later, Tina's mother told her to invite the girl back. 'But Mamma,' she wailed, 'we only eat polenta!'"\ Tina's dinner guest (polenta or no, Assunta insisted) was her classmate at the Dante Alighieri Elementary School, whose two long wings and train station-style clock seemed grandiose to nine-year-old eyes accustomed to a village schoolhouse. Assunta had enrolled Tina with the expectation that she would be assigned, at her age level, to the third grade. She failed the placement examination, however, and a note was made in her record: "does not know the Italian language." Humiliated, she was sent to the first grade along with her little sister Gioconda.\ The event made a profound impression upon Tina, installing in her an irrational and indelible self-image as intellectually inferior. A quarter century later, while offering a journalist a thumbnail sketch of her life, she zoomed in on this incident. "[S]he went to the educational establishment and was sent back to the lower grades," her interviewer reported; "in sum she considers herself untutored." Dogged by a sense that she was insufficiently bookish, Tina sporadically struggled to compensate by diligent reading and study. One friend (an artist) would describe Tina, in her late twenties, as "the most cultivated person," while another (a librarian) asserted that she was intelligent and sensitive but an out-and-out "mediocrity" in terms of erudition. Her formal education probably totaled four years. Later, overcome by feelings of inadequacy in the presence of literati, Tina would mask them with silence. In the remembering and telling of her youthful mortification, she seems to have nearly forgotten that, by spring, she was fluent in Italian and was promoted to the second grade with an almost perfect score of fifty-nine out of sixty. That Tina was resilient and quick-minded, no one doubted.\ For years, Tina had listened to uncounted tales of Udine, but now she drank in its sights, sounds, and smells for the first time, and she was smitten. A friend remembered the adult Tina speaking "of Udine with such fervor, such force, despite the fact that she had departed, I won't say in a stampede, but, well, the way so many Italians did, under very difficult circumstances...." But she left little testimony about her hometown. At best, we have intimations of childish amusements such as a school holiday declared so all could attend Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, its big top pitched at the end of Via Pracchiuso. Every November, for the Saint Catherine's Day Fair, Bläser's traveling Gigantic Cinema would roll onto the green at the other end of Via Pracchiuso, and, despite the family's dismal fortunes, the young Modottis must have found ways to be among goggling and shrieking audiences as Bläser's screens flickered with such epics as Ali Baba and Grandpa Chases the Cat for His Grandchildren. More memorable to Tina was an excursion to Venice, which flooded into her mind's eye years later as she read Theodore Dreiser's travel essays. "Think of these old stone steps," Dreiser had written, "white marble stained green, loved by the waters of the sea these hundreds of years...."\ There were also casual visits to Pietro Modotti's photographic studio. In his early forties, Giuseppe's younger brother—a dynamo with piercing brown eyes and a mustache of the exuberant style favored by the Modotti brothers—had abandoned the butcher's trade and become one of Udine's preeminent photographers. Pietro championed crisp landscapes and architectural studies, although, for portraiture, he preferred what he termed the "intense soft focus," achieved by a method of candlelight photography, which he tirelessly promoted in photographic journals. Flattering and proficient, his sepia- and gold-toned portraits of men in fashionable otter-skin hats, women in off-the-shoulder gowns, and children stiff in summer linens adorned the town's finest overfurnished bourgeois parlors.\ It is hard to say what effect the existence of a photographer uncle had on Tina Modotti. At the Studio fotografico Modotti, Tina experienced a first pungent whiff of sodium hyposulfite up her nostrils and her first glance at a print magically "coming up." Besides making material contact with the métier, she might have observed the passion with which her uncle stopped short—pipe clenched between his teeth, jacket pockets sagging with tools—to expound upon the fine points of optics, lighting, or composition. Like radical politics, photography was part of the Modotti family repertoire and thus within Tina's mental range of possibility. In view of the financial support Pietro provided his brother's family, photography's strongest connection, in the child's mind, may have been to comfort and security such as she seemed unlikely ever to enjoy.\ In 1909, Pietro closed shop temporarily, traveling to Paris, where he learned the Lumière brothers' novel autochrome color process (which he later introduced in Italy) and to the United States for a reunion with his brothers Giuseppe, Francesco, and Angelo. With little to show for two years in the East, Giuseppe had struck out for San Francisco, which was rebuilding after its devastating 1906 earthquake and advertising excellent machinists' wages of $3.75 a day. However, a series of fortuities propelled him instead into opening a photography studio with a compatriot named Augustino Zante. Using skills (and perhaps venture capital) picked up from Pietro and Americanizing his name to Joseph, Giuseppe did business from a second-floor shop in the city's thriving Italian quarter. "MODOTTI JOSEPH & CO. (J. Modotti and A. Zante)," read his boldfaced advertisement in the 1908 City Directory. "Artistic photographers and all kinds of view work." But the district boasted a fraternity of photographers, and the affair failed within the year. Ever sanguine, Giuseppe offered his services as "machine shop, marble working, machinery made and repaired" and astutely listed a telephone number.\ In contrast to her husband, Assunta could only have been disheartened by their situation four years after his precipitous departure. Even with Mercedes on a factory production line, the family barely kept bodies and souls together. Tina, too, was obliged to drop out of school and take a series of odd jobs, culminating in stints at a silk-reeling mill, where she worked ten-hour days for a pittance.\ Udinese sweatshops were typically unembellished high-beamed wooden-floored cracker boxes, chilly or sweltering, according to the season. As a beginner, Tina was put to work scooping up silk cocoons that bobbed in basins of hot, foul-smelling water. Hers was the tedious task of peeling off their netlike coverings and groping, as it was phrased, for their filament ends. A few days on the job turned her hands swollen and raw, and her thumbs throbbed from rubbing against the strands of silk, so fine that they were nearly invisible, yet as durable as steel. With experience, she was promoted to a spot in the chain of steam-powered skein winders that twisted gossamer spun thread quickly and evenly into silk bricks. Arranged in long ranks, ten-, twelve-, or thirteen-year-old girls, pale and hollow-eyed, their pinned-back hair sprouting tendrils limp with perspiration, operated the machinery with such alacrity that arms and hands were a flying blur.\ At their backs paced the overseers, middle-aged men in ill-fitting suits who scrutinized the bricks for irregularities or breaks. If a worker's output was deficient, she had to answer a dreaded summons to the "big table," but if skeins were piling up lustrous and regular, silk reelers were sometimes allowed to sing as they toiled. At first pianissimo and barely audible over the whirring of machinery, the juvenile voices would soar into the popular "They Call Me Mimi" from La Bohème or "Ves dôi vôi che son dôs stelis," a Friulian love song they had all been humming since childhood. Tina was one of the rare Modottis unblessed with an enchanting voice, but she adored music and would have perceived how it lifted the workers above the stink of silk gum, chapped hands, aching feet, and dreariness.\ After six years, Giuseppe scraped up the cash to summon Mercedes to San Francisco as Tina graduated to a weaver's position, almost certainly at Domenico Raiser e Figlio's velvet, damask, and silk establishment near her home. It was more highly skilled labor, slightly more lucrative, but no less frazzling or unstable. As hands shifted and shunted at breakneck speeds, Tina's heart was absorbing and memorizing the wretchedness walled up in Udine's factories. Her own hardship transmuted into perceptiveness and sympathy, it would one day inform her photographs of underage Mexican workers, their wistful faces, coarse and shapeless garments, and resolute gaits.\ She would understand hunger as well, for the Modottis' diet had grown ever leaner. As an indigent student, Tina had been given free lunches—unvaryingly a chunk of white bread, some Emmental cheese, and a hunk of salami—but now she fended for herself at midday. Sometimes the family went dinnerless as well, which set six-year-old Beppo into jeremiads. Yolanda told this tale:\ \ \ Our fire and candles had gone out, as often happened. My mother and I were waiting for Tina, hugging each other to keep warm. We were sad and dejected because there was no light and nothing to eat. When there was food, I went to meet Tina, anxious to give her the good news....\ That night we finally heard the sound of her footsteps. She was running, an unusual occurrence since she was usually so tired that she walked slowly despite the chill.\ Opening the door, she cheerfully said: "Guess what I have brought you?" Approaching us, who could not see, she put a package on my mother's knees, saying, "Bread, cheese, salami! Enough to last until tomorrow!"\ "How did you get them?" asked my mother. Hesitant, but trying to present the fact as normal, she told us that she had never really liked the blue scarf that Aunt Maria had given her and that the factory girls, on the other hand, had admired so much that she had decided to raffle it off. Wasn't that a good idea?\ When I was older, I understood why my mother began to cry while Tina, crouched on her knees, repeated that she did not like the scarf. It was strange because she had shouted with joy when they gave it to her, and it was, in fact, the only item of quality in her scanty winter wardrobe. When I realized how brave the little liar was ... I admired her a great deal and felt a great respect for her.\ \ \ Tina was too modest to include the anecdote in her own repertoire except by aphorism. "Misery and hunger unite a family more than riches and comfort," she once told a companion.\ Her summons to America did not arrive until a year and a half after Mercedes's. To please Assunta, Tina took catechism lessons that spring at the Catholic Church of Saint Anthony, and, with Aunt Anna as her sponsor, was confirmed by the archbishop of Udine. At no time in her life did Tina evince religious faith, and, a few years later, she would declare outright that she had "[no] belief or religion." Taking a page from her father's book, she acquiesced to the sacramental ceremony, but precious few friends would ever be privy to the secret.\ On June 22, with a big send-off and many maternal admonitions, Tina departed Udine by rail for Mestre, Milan, and Genoa. On the eve of her seventeenth birthday, she must have been suffused by two mental images of herself in the world. One was her mother's outlook, by which everything had its beginning, ending, and meaning in the Mondini and Modotti clans, in campanilismo, that which lies within earshot of one's campanile. Family connections were bedrock; emigration, even if it lasted a lifetime, was by definition temporary. Such nineteenth-century notions held an appeal for Tina and would prompt her, at the startlingly young age of twenty-six, to avow that she had "always expressed the desire to be buried in Italy." Simultaneously, she was seduced by her father's joy in rolling with the punches and by his incessant reinvention of self. Leaving Udine overturned her presumed destiny as the daughter, granddaughter, and great-granddaughter of Friulians. The psychic voyage proved inseparable from the physical voyage and, from now on, her journeys would be frequent and almost always one-way.\ Tripping up the gangplank of the German steamship SS Moltke, Tina affected one of the dashing homemade ensembles of which Mondini women had the knack. On her head sat what she later realized was a "ridiculous" hat decorated with artificial flowers and fruit. Barely clearing five feet, soft-spoken, with big, watchful, shining eyes, Tina had a doll-like quality about her. The Moltke docked briefly at Naples, where more emigrants crowded aboard, over a thousand in all. As the ship weighed anchor, a shimmering Neapolitan skyline was to be Tina's last glimpse of Italy.\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from Shadows, Fire, Snow by Patricia Albers Copyright © 2002 by Patricia Albers. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

PrefacePt. ITina1Ch. 1Friuli and Austria (1896-1913)3Ch. 2San Francisco (1913-1918)22Pt. IIMadame de Richey43Ch. 3Lompoc and Los Angeles (1918-1921)45Ch. 4Los Angeles and Mexico City (1921-1922)67Ch. 5Mexico City and Los Angeles (1922-1923)90Pt. IIITinisima113Ch. 6Mexico City (1923-1924)115Ch. 7Mexico City (1925-1926)140Ch. 8Mexico City (1927-1928)164Ch. 9Mexico City (1928-1929)189Ch. 10Mexico City (1929-1930)213Pt. IV[Tov. Modotti]237Ch. 11Berlin and Moscow (1930-1932)239Ch. 12Moscow and Paris (1932-1935)261Pt. VMaria283Ch. 13Spain (1936-1939)285Ch. 14Mexico City (1939-1942)311Endnotes335Permissions361Index363

\ Gail JaitlinTina Modotti is perhaps best known as the lover and model of photographer Edward Weston, but she was also an actress, model, and political activist. An accomplished photographer in her own right, Modotti was responsible for a number of striking and well-regarded photographs, although she worked in this field for only 7 of her 43 years. Figuring out exactly who Modotti was, or who she pictured herself to be, is the aim of Patricia Albers's new biography, Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti. \ Born in Italy in 1896, Modotti endured a childhood of poverty and displacement. Moving from town to town while her father looked for work, Tina dropped out of school at age 11 to go to work in a silk mill. She finally joined her father in San Francisco when she was 17 he brought over his children and wife one or two at a time, as he could afford to, but her early experiences helped inform her later political sensibilities and her photographs of Mexican workers.\ In San Francisco, she worked for a short time as a seamstress before becoming involved with local Italian-language drama troupes. She was a fixture in San Francisco's circle of Italian bohemians and artists and soon became well known as an actress and artist's model. A dark-haired beauty with full lips and smoky eyes, Tina had no difficulty meeting men. Her first true love was Roubaix de l'Abrie Richie Robo, for short, a debonair charmer who dabbled in painting and writing, and with whom she moved to Los Angeles where she had a brief career as a silent film actress and then to Mexico City. Her second love was Edward Weston, the photographer, for whom she modeled in L.A. and with whom she took up residence in Mexico City after Robo's tragic early death from smallpox.\ It was not until she was 27 that Modotti started taking photographs, and even then it was in the long, dark shadow of Weston. A well-known photographer by then, Weston was interested in breaking with previous formal tradition and exploring composition and light. He and Modotti set up a studio together, where they took portraits for money while pursuing their more artistic interests.\ In the 1920s, Mexico City was an exciting place to be. The revolution had just ended, and a cultural revolution was taking place. The new minister of education was distributing freshly printed volumes of the works of Homer and Tolstoy to the masses; muralists had been hired to paint enormous public paintings of traditional Mexican subjects. As Albers writes, "Intellectuals who had once looked to Europe for cultural revelation now turned their backs upon the old continent, embracing instead the genius of peasants and indigenous peoples.... [Lured by] vibrancy and ferment, anticipating inspiration, and titillated by skirmishes between marauding guerilla bands...foreign pilgrims...board[ed] trains and boats bound for Mexico."\ It was against this backdrop that Modotti started her career in photography. At first experimenting only with still lifes especially flowers, Modotti was eventually able to purchase a Graflex camera, which allowed her to dispense with a tripod and take to the streets. Her most vibrant pictures are those of Mexican workers and peasants. It was here that she found her true voice and was able to break away from Weston's influence.\ Her political beliefs, which informed so much of her photography, were ultimately to blame for cutting short her professional career and perhaps her life. She became a Communist upon first moving to Mexico, in part because of the political fervor among her social milieu but also as a response to fascism and Mussolini, who she believed was destroying her precious homeland. After her relationship with Weston ended, Modotti became involved with Jose Mella, a Cuban revolutionary who was assassinated as he walked down the street with Modotti. Harassed by officials and suspected of spying, she was eventually deported to Berlin in 1930 and spent a peripatetic decade traveling around Europe as a revolutionary. Although she took some more pictures, she never found another subject that intrigued her as much as the Mexican people; eventually, she gave photography up entirely. When she died in Mexico at the age of 43, it was under mysterious circumstances. She'd been back in the country less than a year.\ In this evocative portrait, Patricia Albers does a wonderful job invoking the sights, sounds, and smells of life in the bohemian circle of Mexico City circa 1925, when the very air seemed infused with the excitement and ardor that surrounded activists and artists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. But Modotti remains the primary focus of the book, and a fascinating subject she is. To her credit, Albers focuses on Modotti's artistic endeavors as well as on her romantic involvements, which is not an easy task. The artist's romantic life threatened always to overshadow her photography, and the one source of insight into Modotti's mind, her personal journal, was burned, along with many of her letters. Albers's portrait is, then, a welcome introduction to a woman who has remained too long in the shadows.\ --Gail Jaitin\ \ \ \ \ \ Sarah ColemanIn Edward Weston's photographs of the Italian beauty Tina Modotti, the subject assumes various identities. An early series, circa 1921, is all soft-focus, shadowy romanticism, emphasizing the model's heavy eyelids and full mouth, with her slender fingers often reaching out to rest on her chin or shoulder. In sharp contrast is a mid-'20s series of nudes shot in bright daylight, with dark shadows slicing across Modotti's slim form while she suns herself on a patio. At around the same time, Weston made intense close-ups of Modotti's face that reveal both her sadness and her strength, endowing her with a kind of monumental grace.\ These shifts show how Weston evolved as a photographer, but they also demonstrate Modotti's endless ability to reinvent herself. As Patricia Albers writes in her new biography, Shadows, Fire, Snow, Modotti was a "shape-shifter," a woman who was, at different times, an actress, a photographer, a revolutionary and an international undercover agent. By the time she died, in 1942 at the age of 45, Modotti had packed several lifetimes into one short span. She once jokingly remarked that her profession was men, and given the number and intensity of her romances, perhaps it's not so surprising that she expired early.\ At this point, writing a new biography of Modotti represents a tough brief. Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary by Margaret Hooks was called "definitive" in the New York Times Book Review in 1993, and the same year saw the publication of Mildred Constantine's Tina Modotti: A Fragile Life. Albers herself is in competition with a 1991 Italian biography just published in its first English translation, Pino Cacucci's more modestly titled Tina Modotti: A Life. Granted, she's a fascinating subject, but does the world need any more biographies of Modotti?\ Albers thinks so, and she has a reason: a cache of previously hidden letters and photographs handed over to her by a cousin of Modotti's first lover, the extravagantly named Roubaix de l'Abrie Richey (Robo to his friends). Following a trail from these letters, Albers does uncover some new information -- for example, that Robo and Modotti faked their marriage. While this isn't exactly stop-the-presses stuff, it does throw light on the ways Modotti stage-managed her image. The book also features some of the lost photographs from the cache, including some early snapshots that make revealing counterpoints to Weston's beautiful but stagy images.\ "I put too much art in my life," Modotti once wrote to Weston. "Consequently I have not much left to give to art." Her affair with him and her growth as a photographer make for fascinating reading, but the most dramatic phase of her life began when, in the spring of 1929, she fell in love with the charismatic Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella. She was at his side later that year when he was brutally assassinated, and shortly thereafter she was plunged into a Kafkaesque nightmare when she was framed for his murder. She never fully recovered, and her later stint as a Communist apparatchik in Moscow led to conspiracy theories about her own death 13 years later.\ Albers writes sensitively of Modotti's grief and of the years in Moscow, where her "temperament and strength of purpose" made her "manifestly gifted for covert work." Unfortunately, though, a determination to trump all previous accounts of her subject's life sometimes leads Albers to become bogged down in details. Most readers, for example, will probably feel that they didn't need to know the name of every single Communist sympathizer who passed through Modotti's Mexico City apartment in 1927. They might have been better served by more analysis of Modotti's photographs -- her delicate, abstract studies of wilting roses, her portrayals of Mexican peasants and her didactic still lifes of hammers, sickles and bullets.\ Still, Albers has provided an authoritative portrait of a complex individual -- a portrait that, like a Weston photograph, gives equal weight to shadows and highlights. Her extensive study does justice both to Weston's images and to the Modotti of Pablo Neruda's elegy, which tells of a woman for whom "bees, shadows, fire,/snow, silence and foam combining/with steel and wire and/pollen ... make up your firm/and delicate being." -- Salon\ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyArt historians have called Tina Modotti (1896-1942) "the best-known unknown photographer of the 20th century." She also acted in silent films in Hollywood, went to Mexico with Edward Weston in 1922, was a nurse in Spain's Civil War and a prominent Communist, antifascist and internationalist. Partner to equally extraordinary men, friend to the most creative minds of her generation, she died alone in a taxi cab at the age of 46. Shadows, Fire, Snow is her first truly satisfying biography. Patricia Albers has built upon Mildred Constantine's Tina Modotti: A Fragile Life and Margaret Hooks's Tina Modotti: Photographer and Revolutionary, but hers is a more deftly researched book that takes greater risks. In tightly written passages--almost too dense at times--she beautifully evokes pivotal scenes in Modotti's artistic and political development, revealing her generosity of spirit and the passionate commitment to her ideals that kept her moving from country to country and eventually drove her to give up her art. This is a biography divided by place--Italy, Austria, Hollywood, Mexico City, Berlin, Moscow, Madrid--and about a woman who longed to be rooted to a place, but who couldn't allow herself to settle down. Albers's understanding of this contradiction provides the narrative tension that makes this biography such riveting reading (and great film material). Throughout Modotti's short life, she counted among her friends and co-workers Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, American writer John Dos Passos and Russian revolutionary and feminist Alexandra Kollontai, among many others. Modotti's photographs were often documentary in nature, what Carleton Beals called seeking the "perfect snapshot." Albers's rendition of Modotti's life goes a long way toward allowing us to understand this extraordinary woman.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalLooking beyond Modotti's liaisons and life as a photographer in Mexico, Albers takes her subject off the pedestal created by Edward Weston's ethereal photographs. In this accessible work--the first comprehensive biography--Albers sees the very human Modotti as a passionate artist, inexhaustible political organizer, and modern woman set on finding fulfillment. (LJ 4/15/99) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Helen YglesiasIt is impossible to write the life of Tina Modotti and not face the full impact of questions raised by the violence and tragedy of the major struggles of our century—between those who tried to establish economically just societies, those who fought for the status quo and the innocents in between...Patricia Albers makes her way within these terrible alternatives with sympathy for her subject and a free display of all the information she has garnered, delivering a valuable document of what is known about an important woman's life.\ —The Women's Review of Books\ \ \ \ \ Ted Loos...[Attempts] to make sense of the colorful traces she left behind...[Gives] Modotti her due, both in art and in life.\ — The New York Times Book Review\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA finely detailed portrait, full of shadows and highlights, of the mysterious woman who was actress, well-regarded photographer, Communist secret agent and compassionate humanitarian. An earlier biography of Tina Modotti (Tina Modotti: A Life, p. 189) did little more than roll the credits on the story of a beautiful Italian immigrant to San Francisco who became a pioneer in documenting the lives of Mexican workers and farmers with her Graflex camera. Art historian Albers has meticulously researched Modotti's life, from a poverty-stricken childhood in northern Italy, to a glamorous turn in Hollywood, and after moving to Mexico, a growing commitment to photography under the tutelage of her lover, photographer Edward Weston. After Weston returned to California, Modotti was introduced to Communism by artist Xavier Guerrero, and she joined the party. Although her reputation as a photographer was growing, so was her reputation as Communist agitator, and by early 1930, she was deported from Mexico, with Mussolini's blackshirts also on her trail for antifascist activity. She landed in Moscow, working for Red Aid, an international relief organization, but also a cover for assignments delivering money and messages to party members throughout Europe. In Moscow she began an 11-year sexual and political liaison with the notorious Vittorio Vidali, the source of many not always accurate stories of Modotti's later life. Dispatched to the Spanish Civil War together, they never returned to Moscow, but instead found their way back to Mexico (with false papers). Modotti died somewhat mysteriously there in 1942, ending a life marked with tragedy and scandal, but also one dedicated first to art and thento humanity. The title of the book is from a poem written for Modotti's memorial service by Pablo Neruda. An absorbing, if occasionally overwrought story (Modotti seemed to produce that effect in her admirers) of both Tina Modotti and the tumultuous times she lived in. (60 b&w photos, not seen)\ \