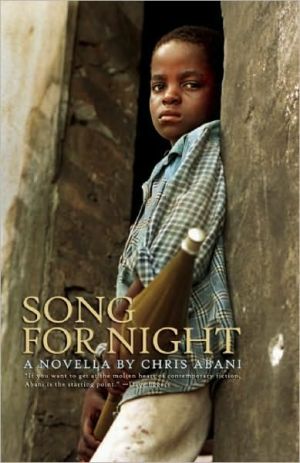

Song for Night

"Not since Jerzy Kosinski’s The Painted Bird or Agota Kristof’s Notebook Trilogy has there been such a harrowing novel about what it’s like to be a young person in a war. That Chris Abani is able to find humanity, mercy, and even, yes, forgiveness, amid such devastation is something of a miracle.”—Rebecca Brown, author of The End of Youth\ "The moment you enter these pages, you step into a beautiful and terrifying dream. You are in the hands of a master, a literary shaman. Abani casts his...

Search in google:

Abani's new novella furthers his tremendous success in becoming today's most acclaimed young AfricanThe New York Times - Maud CaseyIn a famous introduction to Isaac Babel's Collected Stories, Lionel Trilling used the phrase "lyric joy" to describe Babel's talent for transforming the unimaginably ugly violence of war into something sublime through prose just as fierce and precise. In the novella Song for Night, Chris Abani, the author of GraceLand, which won the PEN/Hemingway Award in 2005, achieves a similar kind of lyric joy in his moving story of a 15-year-old West African orphan with the unlikely name of My Luck.

Song for Night\ a novella \ \ By Chris Abani \ Akashic Books\ Copyright © 2006 Chris Abani\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-1-933354-31-6 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Silence Is a Steady Hand, Palm Flat \ What you hear is not my voice.\ I have not spoken in three years: not since I left boot camp. It has been three years of a senseless war, and though the reasons for it are clear, and though we will continue to fight until we are ordered to stop-and probably for a while after that-none of us can remember the hate that led us here. We are simply fighting to survive the war. It is a strange place to be at fifteen, bereft of hope and very nearly of your humanity. But that is where I am nonetheless. I joined up at twelve. We all wanted to join then: to fight. There was a clear enemy, and having lost loved ones to them, we all wanted revenge.\ If you are anything like Ijeoma you will say that I sound too old for my age. She always said that: said, because although her name in Igbo means Good Life, she died young, a year ago, aged fourteen, her wiry frame torn apart by an explosion. Since she couldn't speak either, it might be misleading to say she said, but we have developed a crude way of said talking, a sort of sign language that we have become fluent in. For instance, silence is a steady hand, palm flat, facing down. The wordsilencio, which we also like, involves the same sign with the addition of wiggling fingers, and though this seems like a playful touch, it actually means a deeper silence, or danger, and as in any language, context is everything. Our form of speech is nothing like the kind of sign language my deaf cousin studied in a special school before the war. But it serves us well. Our job is too intense for idle chatter.\ I am part of a platoon of mine diffusers. Our job is to clear roads and access routes of mines. Though it sounds simple, our job is complicated because the term access routes could be anything from a bush track to a swath cut through a rice paddy. Our equipment is basic: rifles to protect against enemy troops, wide-blade machetes for clearing brush and digging up the mines, and crucifixes, scapulars, and other religious paraphernalia to keep us safe.\ We were not chosen for our manual dexterity or because of our advanced intelligence, though most of us are very intelligent. We were chosen simply because we were small, slight even, and looked like we wouldn't grow much in the nutrition-lacking environment of a battlefield. We were chosen because our light weight would protect us from setting off the deadly mines even when we stepped on them. Well, they were right about the former, even now at fifteen I can pass for an average twelve-year-old. But they were so wrong about the latter. Even guinea fowl set off the mines. But they must have known: that is why they imposed the silence. I finger the scar on my throat that marks the cut that ended my days of speech.\ There is a lot to be said for silence, especially when it comes to you young. The interiority of the head, which is a misnomer-misnomer being one of those words silence brings you-but there is something about the mind's interiority no less that opens up your view of the world. It is a curious place to live and makes you deep beyond your years and familiar with death. But that is what this war has done. I am not a genius, though I would like to be, I am just better versed at the interior monologue that is really the measure of age, of the passage of time. Why do I say this? Because when we say the passage of time we mean awareness of the passage of time, and when we say old, we really mean experienced. I know all this because my job requires me to concentrate on every second of my life as though it were the last. Of course if you are hearing any of this at all it's because you have gained access to my head. You would also know then that my inner-speech is not in English, because there is something atavistic about war that rejects all but the primal language of the genes to comprehend it, so you are in fact hearing my thoughts in Igbo. But we shan't waste time on trying to figure all that out because as I said before, time here is precious and not to be wasted on peculiarities, only on what is essential.\ I have become separated from my unit. I don't know for how long since I have only just regained consciousness. I am having no luck finding them yet, which is ironic given that my mother named me My Luck. But as Grandfather said, one should never stop searching for the thing we desire most. And right now, finding my unit is what I desire most. We were all together, when one of us, Nebuchadnezzar I think it was, stepped on a mine. We all ducked when we heard it arming-that ominous clicking that sounds like the mechanism of a child's toy. The rule of thumb is that if you hear the explosion, you survived the blast. Like lightning and thunder. I heard the click and I heard the explosion even though I was lifted into the air. But the aftershock can do that. Drop you a few feet from where you began. When I came to, everyone was gone. They must have thought I was dead and so set off without me: that is annoying and not just because I have been left but because protocol demands that we count the dead and tally the wounded after each explosion or sweep. Stupid fools. Wait until I catch up with them, I will chew them out; protocol is all that's kept us alive. Counting is not just a way to keep track of numbers, ours and the enemy's, but also a way to make sure the dead are really dead. In training they told us to maximize opportunities such as these to up our kill ratio; for which we would be rewarded with extra food and money we can't spend. I like to pretend that I do it to ease the suffering of the mutilated but still undead foes, that my bullet to their brain or knife across their throat is mercy; but the truth is, deep down somewhere I enjoy it, revel in it almost. Not without cause of course: they did kill my mother in front of me, but still, it is for me, not her, this feeling, these acts. The downside of silence is that it makes self-delusion hard. I rub my eyes and spit dirt from my mouth along with a silent curse aimed at my absent comrades. If they'd checked they would have noticed that I wasn't dead.\ The first thing I do is search for Nebu's body. That's the way it is laid out in the manual (although of course none of us has ever seen the manual but Major Essien drummed it into us and we know it by heart): first locate and account for friendly casualties, then hostiles; in that order-friend, then foe. The funny thing is, though I search, I can't find Nebu's body. There are no other bodies either, which means the enemy hasn't been around.\ Let me explain something, which on the surface might sound illogical but isn't. We all lay land mines, the rebels and the federal troops, us and the enemy, but we do it in such a hurry that no one bothers to map these land mine sites, no one remembers where they are. That and the fact that territory shifts between us faster than sand tracking a desert, ground daily gained and lost, makes it hard to keep up. Given that the mine diffusers and scouts are always the advance guards, it is easy to see how minefields are often places where we intersect. In this case however it seems like there was no enemy, that Nebu simply got careless; or unlucky.\ My first instinct is always survival so I abandon the search as quickly as I can and get out of the open. I debate whether to head for the river, fifty yards to my left, or the tree cover, seventy yards or so to my right. I choose the river. Rivers are the best way to keep close to habitation as well as the fastest means of travel. I hug the banks in the shadows and carefully observe any developments, of which I must confess there are very little. So far I haven't met anybody and I haven't found any traces of my unit. It is not good to be alone in a war for long. It radically decreases your chances of survival.\ But my grandfather always said, "Why put the ocean into a coconut?"\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Song for Night by Chris Abani Copyright © 2006 by Chris Abani. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ Louise BernardThe beauty of the work lies in My Luck's haunting narration, an "inner-speech" that fittingly is one of pained detachment. His calm meditation on his role in the war, his acknowledgment of his guilt and shame—a fraught combination of choice and imposition as he fights, at first, under the rule of a brutal commander and in revenge for his parents' slaughter—is filtered through a voice that, strangely enough, is nonexistent. My Luck, like his fellow rebels, has been silenced. The platoon is mute, their vocal cords severed so that wounded screams do not interfere with the precise operation of diffusing and reclaiming the mines. Instead, the group communicates through a simple system of signs, a tender, indeed touching way of reaching out to one another… In a war where "territory shifts" between the rebels and their enemy "faster than sand tracking a desert, ground daily gained and lost," My Luck somehow holds tight to the need to feel compassion, to exercise some form of ethical stability in a world gone mad.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Maud CaseyIn a famous introduction to Isaac Babel's Collected Stories, Lionel Trilling used the phrase "lyric joy" to describe Babel's talent for transforming the unimaginably ugly violence of war into something sublime through prose just as fierce and precise. In the novella Song for Night, Chris Abani, the author of GraceLand, which won the PEN/Hemingway Award in 2005, achieves a similar kind of lyric joy in his moving story of a 15-year-old West African orphan with the unlikely name of My Luck.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn his latest novella, Abani renders the inner voice of mute 15-year-old My Luck, the boy leader of a platoon of mine sweepers in an unnamed war-torn African country. When he was 12, the then volunteer rebel had his vocal cords severed (the rest of his team received the same treatment), "so that we wouldn't scare each other with our death screams." At the opening of the novella, My Luck awakens after an explosion to find that he has been separated from his unit. During his journey to find his platoon, he reflects on the events of his violent life. Abani is unafraid to evoke My Luck's dark side, and though My Luck's experience with killing is "a singular joy that is perhaps rivaled only by an orgasm," his stock-taking also touches on guilt at witnessing his mother's murder, ambivalence about his imam father and tenderness for Ijeoma, a girl in his platoon killed by a mine. Initially, the present-tense narration is at odds with My Luck's inclination toward memory and reflection, but the story becomes more immersive and dreamlike (and, strangely, lucid) over the course of My Luck's quest. Abani finds in his narrator a seed of hope amid the bleak, nihilistic terrain. (Sept.)\ Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information\ \ \ \ \ KLIATT\ - KLIATT Review\ The nightmare of war in West Africa is vividly told in flashbacks through the eyes of My Luck, a 15-year-old boy separated from his platoon after a mine explosion. He wanders the countryside, confused and hungry. For My Luck, the last few years have been full of upheaval. Both of his parents are dead, and he even killed his own uncle after the man moved in with his mother. Once he joins the military, My Luck becomes part of a special platoon trained to safely defuse mines. These young people become best friends, though after their training their vocal cords are cut, and they must communicate in a crude sign language. My Luck explains that one of the reasons for the operation is that if a platoon member has an accident with a mine, the others won't be frightened by the death screams. They move from village to village, sometimes committing terrible acts against innocents. My Luck carves crosses on his arm to commemorate his fallen friends as well as the people he has killed. In spite of the brutality of war, he finds love with Ijeoma, one of the other soldiers. She comforts him when his platoon leader, nicknamed John Wayne, forces him to rape a woman. The two support each other, and after she is killed, he feels lost and sad. My Luck's journey is full of dreams, memories, and musings about life and death. At certain points, readers will wonder which events are real and which are dreams, as the narrative blends these moments together seamlessly. The graphic scenes of violence make this book more suitable for older readers who are interested in stories of war. Age Range: Ages 15 to adult. REVIEWER: Olivia Durant (Vol. 42, No. 1)\ \