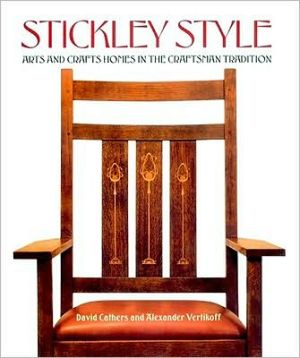

Stickley Style: Arts and Crafts Homes in the Craftsman Tradition

Beginning in the very first year of the twentieth century, Gustav Stickley made furniture that is prized almost a hundred years later for its honesty, simplicity, and usefulness. As a designer and manufacturer who emphasized careful workmanship, respect for natural materials, and simple lines, Stickley had a profound impact on the look of American homes. Today, Arts and Crafts design — synonymous with Stickley to many people — has become an American passion.\ Elegantly designed and lushly...

Search in google:

Beginning in the very first year of the twentieth century, Gustav Stickley made furniture that is prized almost a hundred years later for its honesty, simplicity, and usefulness. As a designer and manufacturer who emphasized careful workmanship, respect for natural materials, and simple lines, Stickley had a profound impact on the look of American homes. Today, Arts and Crafts design — synonymous with Stickley to many people — has become an American passion.Elegantly designed and lushly photographed, Stickley Style is the first major publication to explore in full photographic color the central role Stickley played in the development of Arts and Crafts design. Author David Cathers invites us into the world of this influential furniture maker and provides us with an insider's tour of some of the country's most important Stickley collections and interiors. Here, imbued with pure and simple lines, are the comfortable Morris chairs, the upright settles, the solid oak chests, the hammered metalwork, and the delicate textiles that have come to epitomize Stickley's style.But Stickley was more than a furniture maker — he was a one-man phenomenon: book and magazine publisher, proponent of a simple and natural lifestyle, and de facto leader of the Arts and Crafts movement in America. Calling the composite of his ideas and activities "the craftsmanship of life," he used the word Craftsman to refer to his houses, his furniture, and his magazine.Stickley Style captures the excitement and revolutionary zeal of these ideas and this era, a time when Victorian fussiness was being abandoned in the search for a modern way to live. The book opens with avivid description of the Craftsman idea and describes Stickley's vision of ways to make a house conducive to a life of beauty and contentment. Cathers then goes on to show us the collections in a series of stunning Arts and Crafts homes, including Stickley's own family home in New Jersey. Finally, for those who want to furnish their own homes with appropriate reproductions, an extensive catalogue presents everything from Stickley tables and sideboards to tall case clocks and metal door latches. Throughout, specially commissioned photographs by Alexander Vertikoff show the overall harmony that will make the Stickley style as much a favorite for the new century as it was for the last.USA Today - Ann PrichardThis book is an excellent viewing and source book, providing photographic entree to some of the country's finest Stickley collections. A new book on Stickley's work and philosophy is sure to make a perfect gift for his fans.

Gustav Stickley and the Craftsmanship of Live\ Gustav Stickley loved music, especially opera. He was stirred by the beauty of gardens and came to relish working in the soil. He cherished his wife and children, even though the demands of his career often kept them apart. In later life, opening his blue tin of Edgeworth tobacco and filling his corncob pipe, he delighted in telling vivid tales to enraptured grandchildren. But his greatest passion was wood. As his grandson Gustav Stickley III recalled, "He would caress a piece of wood. As burly and as big as he was...when he touched a piece of wood it was like a caress...Even as a boy I could see this". A maker of furniture and decorative household objects and later also a publisher, Stickley (1858-1942) became a central figure of the American Arts and Crafts movement that flourished at the beginning of the twentieth century Members of the movement, which arose in England, were distressed by the era's spreading industrialization and criticized factory goods cheaply produced and superficially decorated with garish machine-made ornament that often masked flimsy construction and inferior wood. To them, the new manufacturing system treated workers as little more than machines themselves. The movement bravely sought to remedy these ills by reviving the handicrafts of earlier times, stressing the value of good workmanship, simple design, and the life-enhancing pleasures of honest hand labor.\ In the United States Stickley gathered together many of the movement's shared beliefs and called them the "Craftsman idea." He advocated his version of the Arts and Crafts philosophy in his influential Craftsman magazine beginning in 1901, and in his Craftsman Workshops he produced moderately priced furnishings consistent with its principles and sold them widely. Through his publications and his products, Stickley brought Arts and Crafts ideals into people's daily lives, giving the movement meaning for a large national audience. This has proved to be his unique and lasting achievement.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From the Introduction: Gustav Stickley and the Craftmanship of Life\ THE CRAFTSMAN IDEA\ This was an era of great ferment in the decorative arts, and Stickley felt its irresistible pull. In 1898 he established his own firm, the Gustave Stickley Company (he later dropped the e from his first name), which for the first two years continued to produce revivalist furniture. Stickley had a factory payroll to meet and a family to support, and these responsibilities apparently took priority, he was not yet able to act on the ideas forming in his mind. At the same time he began to experiment with Arts and Crafts design in his shop.\ In the summer of 1900 Stickley introduced his first Arts and Crafts furniture to the trade at the Grand Rapids Furniture Exposition. Some of these early designs seem to have been inspired by Charles Rohlfs, the innovative Arts and Crafts furniture designer and maker whose workshop turned our intricately derailed and often exotic pieces expressing his unique and highly personal aesthetic. Other Stickley designs exhibited at this show suggested his awareness of contemporary European trends written about regularly in the international art journals. Stickley's offerings "met with instant favor," reported the trade magazine Furniture Journal, but his firm apparently made only one significant sale at this show. George Clingman, manager of the Tobey Company, a large Chicago retailer, ordered more than eight hundred pieces of Stickley's new furniture and arranged to market it exclusively under the Tobey name. Within a year the dealings between the two men ended in mutual disaffection, but Stickley's career as an Arts and Crafts furniture maker had begun.\ By 1901 Stickley's designs had grown more confident and had taken on the robust, structural quality that would characterize Craftsman furniture from then on. That same year, with a staff of writers and editors, he began publication of The Craftsman, a monthly magazine intended to publicize his furniture and spread Arts and Crafts ideals. The first issue, in October 1901, was devoted to William Morris, the second to John Ruskin, and the third to medieval guilds (for a time Stickley publicly referred to his firm as a guild).\ Stickley's Craftsman idea, as he defined it in his 1901 catalogue, arose from established Arts and Crafts principles: "...the ideals of honesty of materials, solidity of construction, utility, adaptability to place, and aesthetic effect..." These handicraft-based precepts emphasized plain, functional form, good workmanship, decorative structure, and a respect for natural materials. Stickley applied his newly awakened beliefs to the furniture made in his workshops and, within a few years, to interior design, metalwork, textiles, and the design and construction of houses.\ "Honesty of materials." Stickley valued honesty, by which he meant two things. First, the purpose of a piece of furniture should be immediately apparent in its design. He believed, for instance, that a chair should be "first, last and all the time a chair, and not an imitation of a throne, nor an exhibit of snakes and dragons in a wild riot of mis-applied wood carving." Second, the designer and the artisan should appreciate the nature of their materials and create objects that honestly express that nature. For Stickley, like Frank Lloyd Wright, wood was not meant to be molded or bent into elaborate shapes or encased within thick layers of highly polished varnish that obscured its inborn beauty. It should be cut in straight lines to emphasize the dramatic patterns of its grain, its plain surfaces finished to enhance their natural colors and texture.\ "Solidity of construction." The careful construction of Craftsman furniture reproached the inferior factory wares of the day. As evidence of his furniture's substantial structure, Stickley created designs that made use of tenon-and-key joints, through-tenons pinned with visible dowels, double dovetails, and other forms of exposed joinery. These emphatic functional joints added visual interest to Stickley's pure, plain forms, while making clear exactly how everything was held together. Here was solid construction made visible, designed to be beautiful.\ "Utility." Stickley was an early advocate of what he described as utility. His sturdy, unadorned Craftsman furniture was durable and functional and intended for daily use. It was not designed to be admired solely for its beauty or the status it conferred on its owner.\ "Adaptability to place." The word adaptability appears in Stickley's writings again and again, and the idea of harmony was a leading theme of his work. Good taste for the Victorians had meant assembling and mixing a miscellany of exotic objects Stickley sought to replace this kaleidoscopic approach to design with a unified, harmonious whole: the organic, he believed, must replace the eclectic.\ "Aesthetic effect." Stickley always wanted his designs to be beautiful. Because he typically worked with plain forms, the aesthetic effects of his furniture relied on honesty, utility, harmony, and frankly revealed structure. The integrity of Craftsman furniture created beauty\ Proportion. The heart of Craftsman design, however, is Stickley's mastery of proportion, the relationship of the parts to the whole. The arms of a Craftsman chair, for instance, are placed to ensure the sitter's comfort and brace the frame, but they are also ac the right height and of the right depth, width, thickness, and shape to accord visually with all the other elements of the chair. Stickley adjusted such details with rigorous empirical experimentation on the workshop floor, not according to any prescribed formulas "[E]very model we produce," he wrote, "is studied and tested and modified until. The Craftsman finds it thoroughly satisfactory"\ Color. Stickley cared about color as well. Year after year he experimented with finishing methods that would enhance the natural color, grain, and texture of quartersawn American white oak, his favorite cabinet wood. He worked in matte browns, greens, and silver grays, applying wax or a thin coat of shellac to give the wood a soft, lustrous glow. To complement his furniture he created household objects of hand-worked copper or iron. The copper was given a rich warm brown patina, the iron a dull sheen that Stickley called "armor bright," and all the metalwork was hammered by hand to create irregular, light-catching surfaces that brought gleams of color into a room. He also made Craftsman curtains, wall hangings, and table runners with simple, subtly tinted patterns worked on loose-weave fabrics. With wood, metal, and textiles he recreated the colors and textures of nature and brought them into the home.\ Stickley's thinking quickly evolved, and he began to move away from the idealization of the handmade object that had become a widely accepted Arts and Crafts belief. He recognized that he could produce wares affordable to a middle-class market only by combining skilled hand craftsmanship with an enlightened harnessing of the power of machines, an idea advocated by The Craftsman as early as 1902. From the first, Stickley's Arts and Crafts furniture, with its straight lines and flat surfaces, had relied to some extent on machine processes, and his public embrace of the machine acknowledged the realities of Craftsman production. A year earlier Frank Lloyd Wright had argued this case in his famous lecture. "The Art and Craft of the Machine," and it seems likely that Wright's thoughts influenced Stickley Yet as he pragmatically accepted shifting Arts and Crafts ideologies and took advantage of improving machine technologies, the Craftsman idea remained a central theme in all that Stickley did.\ In time the Craftsman idea grew to include what Stickley defined as the craftsmanship of life — a moral dimension that he believed should guide the life and work of the individual, the family, the nation. His ideas about the simplification of design led to thoughts about the simplification of life and precepts for moral living. He spoke out against the materialism of his age in a way that continues to resonate today, he was a manufacturer with wares to sell, a capitalist in pursuit of profits, but he urged moderation. Such cautions later led to his eloquent essays on the need to protect the natural environment.\ Stickley shared the Arts and Crafts belief in the moral influence of the built environment and emphasized the critical role the home and its furnishings played in shaping character. He thought that poorly made, poorly designed furniture was destructive of good taste, but this was its lesser evil. "Its moral effect," he insisted, "is still more perilous." When Stickley spoke of "the strong-fibered and sturdy oak" from which he built his furniture, he had more than furniture in mind. He was thinking, too, of the moral fiber of the American people.\ A SIMPLER LIFE\ Stickley's Craftsman enterprises achieved considerable success, and by 1902 his factory employed about two hundred workers. That year he completely remodeled much of the interior of a well-known Syracuse structure, the lavish Crouse Stables, and dubbed it the Craftsman Building. Here he had exhibit space for Craftsman wares as well as his business and editorial offices, a lecture hall, his design department, and, in an adjacent single-story building, his new metal workshop. In late 1905 he left this building and moved his offices to Manhattan, dividing his time between Syracuse and New York City.\ A few years later in the gentle, green hills of rural New Jersey he began building Craftsman Farms, an ambitious project meant to combine a crafts colony, a school, and a demonstration farm. He called it his Garden of Eden. Stickley's plans for the 650-acre site were never fully realized, but he lived there happily for several years with his wife, Eda, and their six children. In 1913 he leased a newly completed twelve-story Manhattan office tower and opened it as the Craftsman Building, which encompassed eight floors of retail space, two floors of offices, a floor for club rooms, a library, a lecture hall, and the Craftsman Restaurant at the top.\ Stickley's huge financial commitment to this multistory Arts and Crafts emporium was unluckily timed. The popularity of his Craftsman wares began to decline, and the qualities that had once made them so appealing — their frank composition, hand-wrought surface textures, and muted brown and green earth tones — now looked a little dated as popular taste shifted toward bright colors and formal design. His problems were compounded when war began in Europe in 1914 and the market for household goods waned. Caught between the high fixed costs of the Craftsman Building (its annual rent was $60,000) and failing retail sales, Stickley's firm was bankrupt by 1915. He published the last issue of The Craftsman in December 1916 and then closed down completely. In the years following the bankruptcy he worked briefly with his brothers Leopold, John George, and Albert as a vice president of their amalgamated manufacturing firm, Stickley Associated Cabinetmakers, and then tried unsuccessfully to start several business ventures of his own. In later life he made a few simple, Shaker-like chairs for members of his family, but his days as "The Craftsman" were over.\ Stickley died forgotten in 1942, his designs by then considered irrelevant and without worth. Yet a prediction he made during his Craftsman years has turned out to be true. "Oak furniture that shows plainly what it is, and in which the design and construction harmonize with the wood...will in time become valuable...[and] will be treasured as heirlooms in this country."\ Gustav Stickley's Craftsman idea — his personal, creative response to mainstream Arts and Crafts thinking — had found ever-widening expression in wood, metal, textiles, interior design, and complete homes that settled comfortably into their natural surroundings. In his Craftsman magazine, he had reached out to readers seeking a simpler, better way to live. Throughout his career the Craftsman idea continued to grow and branch out, its roots sunk deep into Stickley's fondness for music and harmony, his desire to live in nature, his idealization of home and family, his love of wood.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From STICKLEY STYLE: OUTSIDE — HOME MAKING\ Under Fragrant Bowers: Porches, Pergolas, and Terraces\ In the pages of The Craftsman, Stickley urged his readers to think of porches, pergolas, and terraces as informal outdoor rooms rather than mere passageways. These structures blurred the distinction between outside and inside and created new and liberating opportunities for family life. As outdoor rooms they put family members into bracing contact with light-filled nature and at the same time offered secluded, shaded settings for quiet relaxation. The wholesome pleasure of vigorous outdoor living was a constant Craftsman theme. The inhabitants of a bungalow or Arts and Crafts-style house were able to work, play, rest, and eat in the open air because these houses were planned to provide space for as much outdoor life as possible. Porches, pergolas, and terraces, reconsidered as living or dining rooms, increased the usable area of the houses and created sturdy settings for lively outdoor play. They had a contemplative aspect as well. Similar to a fireplace inglenook, these sheltered, softly lighted spaces were meant to be restorative retreats from the demands of daily life. They were domestic and withdrawn, protected by stone parapets, flower boxes, and luxuriant vines. The Craftsman declared that "there is a charm in...privacy." Pictured porches were often recessed to further enhance this enfolding sense of peace. Vines of all kinds climbed up porches and tumbled over pergolas, which each tied a house to the world outside. They created green and flowering corridors that led out of the house and into the garden, where members of the family refreshed themselves in the health-giving outdoors.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From CONTINUING THE CRAFTSMAN TRADITION: STICKLEY PURE AND SIMPLE\ The House of Mr. Stickley\ On Christmas Eve, 1901, a fire broke out in Gustav Stickley's Colonial Revival house in Syracuse, New York, where the family had lived for only about one year. Most of the interior was destroyed. The Stickleys were able to save some valuable furniture, silverware, and rugs, but everything else was lost. Looking over the burned-out shell Stickley decided to rebuild. His restoration left the classical details of the facade intact, but the inside was completely remodeled. Stickley had created the first Craftsman residential interior. A year later The Craftsman magazine published. "A Visit to the House of Mr. Stickley," describing this transformed interior and introducing readers to the defining Craftsman virtues of simplicity, informality, and harmony. The formal parlor had vanished, and the downstairs had been redesigned as a large space divided by post-and-panel partitions. The new interior was dominated by oak and chestnut fumed with a potent solution of ammonia, resulting in a warm, rich brown tint that soon became Stickley's trademark color. New floors were laid with chestnut boards of varying widths, walls were paneled with oak planks rising to a rough-textured plaster frieze, and ceilings were heavily beamed Seats and cabinets were now built in, and some of the original sash windows were replaced by casements organized into horizontal bands. Two fireplaces were remade of red brick with stone lintels, and at least one was faced with Grueby tile. These features would reappear in Craftsman houses to come. The Stickley family lived in this house for about eight more years, selling it, along with most of the furniture, when they moved to Craftsman Farms in New Jersey. But around 1919 Stickley's oldest daughter, Barbara, and her husband repurchased it and moved in with their five boisterous children. One day the following year the widowed Gustav, carrying his satchel, stopped by for a two-week visit and ended up taking over a third-floor bedroom, where he lived most of his remaining years. Much of what is known about Stickley's personal life comes from his grandchildren's memories. One indelible impression was his perpetually clean, bracing scent (a residue of the chemicals he used in his experiments to perfect new furniture finishes), which intermingled with the aromatic smoke of his pipe. Penniless in retirement, he cheerfully taught his grandchildren about music and botany and puttered in the family garden. Years later they came to understand the true nature of his legacy. "He was," one grandchild has written, "almost an evangelist in bringing new thoughts and new appreciation of things artistic and new social thinking. That is something that doesn't go bankrupt and he, as an inspiring person, never did go bankrupt." After Barbara's family moved on in the early 1950s, Stickley's house suffered neglect, although some of its original Craftsman furniture is preserved in private collections and museums. In the late 1990s local Arts and Crafts preservationists fought successfully to keep what remained of the house intact. It was subsequently bought by Alfred and Aminy Audi, the current owners of the L. & J. G. Stickley Company, who have stabilized the structure and plan eventually to resurrect this iconic Arts and Crafts site as a study center and museum.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From CONTINUING THE CRAFTSMAN TRADITION: STICKLEY PURE AND SIMPLE\ Kindred Spirits\ THE ALLURE OF THE BROTHERS L. & J. G. STICKLEY\ One day in 1978 Donald Davidoff walked into a New York gallery and saw a long, low oak-and-leather Prairie settle made by the L. & J. G Stickley Company. He had never heard the name Stickley before, but that evening he told his wife, Susan Tarlow, that Stickley was what they were going to collect — after they finished graduate school. In the beginning they bought some of Gustav Stickley's Craftsman pieces but found themselves drawn to the more eclectic and somewhat less austere furniture made by the rival firm established by his brothers Leopold and John George. They especially admired the sleek, sophisticated designs created by L. & J. G Stickley's designer Peter Hansen about 1910, when the firm was calling its Arts and Crafts furniture Handcraft. One of the couple's first Handcraft purchases was a rocking chair of honey-colored quartersawn oak that they still own. Another was a settle, listed the company's catalogue simply as "#220 Settle" but called "Prairie" today because of its dear debt to the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright. Other L. & J. G. Stickley pieces in the Davidoff-Tarlow home near Boston recall the Prairie style — the tall-back Handcraft dining room chairs and two Wright-influenced L. & J. G. Stickley armchairs — but many of the best do not. The double-door Handcraft armoire in the main bedroom is probably one of a kind. In the dining room are two rare early L. & J. G. Stickley pieces a massive china cabinet with long copper hinges and a cellarette (a small cabinet for wine bottles). The glass-and-copper Handcraft lanterns hanging above the dining room table were made for Leopold Stickley's house in Fayetteville, New York. During Gustav Stickley's Craftsman years, he and his brothers kept their businesses separate, a fact lamented at least once by the industry. On Christmas day 1906, "The Tattler" column, a regular feature in the trade magazine Furniture Journal, was devoted to Gustav Stickley and included this report on his brothers. "Charlie is still in Binghamton, the manager of the Stickley & Brandt Chair Company; Albert made an advantageous connection out of which the Stickley Brothers Company, of Grand Rapids, has grown, and four or five years ago Leopold and J. G. Stickley...launched out for themselves. It has always seemed a pity to me that these five brothers could not have combined their forces and worked together." According to family tradition, all the brothers were strong-willed and preferred to work independently, and ir was not until Gustav's bankruptcy that, for about three years, they finally banded together. Today Leopold and John George Stickley rest somewhat in the shadow of their older, more famous brother Bur the handsome, innovative L. & J. G. Stickley designs in the Davidoff-Tarlow collection show how accomplished their firm could be. In the serene interior of this Handcraft house, their work is seen at its best.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From CONTINUING THE CRAFTSMAN TRADITION: STICKLEY AND THEN SOME\ The First Collector\ ONE STICKLEY CHAIR LEADS TO A CLASSIC EXHIBITION\ On March 22, 1960, a Berkeley undergraduate named Robert Judson Clark excitedly sent his sister a postcard about a new find. "Guess what. I looked at my chair last night — at a new angle — and it's a signed GUSTAV STICKLEY...am I happy!" This chair — bought nor because of who had made it but just because Clark liked it — had cost him $5. While in college, Clark had begun researching the early-twentieth-century California architects Bernard Maybeck, Louis Christian Mullgardt, and Charles and Henry Greene. He tracked down turn-of-the-century books and periodicals and eventually found The Craftsman magazine, from which he learned what Stickley's furniture looked like and how it was marked. Soon after identifying Stickley's red decal underneath the seat of his new chair, he found a photograph of an identical chair in the January 1904 Craftsman. With that discovery he began collecting Arts and Crafts In 1972, when he was an assistant professor at Princeton University, Clark created the landmark exhibition The Arts and Crafts Movement in America 1876-1916 and edited its catalogue, both of which refocused attention on long-eclipsed Arts and Crafts furniture, ceramics, metalwork, lighting, textiles, and books. Some of the exhibited pieces were from Clark's own collection, and some still stand in his house near San Francisco (he is now professor emeritus) the Gustav Stickley chair, his original purchase, made about 1903, an L. & J. G. Stickley Morris chair, and a handsome storage chest from an oak bedroom suite made in 1910 by Jewett Johnson, a California manual arts teacher. Today, when collectors are so eager to seek out period Arts and Crafts objects and modern artisans work in the spirit of the movement, it is sometimes hard to realize that this revival is a relatively recent phenomenon. It may, in fact, have begun that day when a student handed $5 to a Pasadena antiques dealer and drove home with a mysterious chair.\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers\ From CONTINUING THE CRAFTSMAN TRADITION: STICKLEY AND THEN SOME\ One True Passion\ A STICKLEY RARITY, UNITED AT LAST\ About twenty years ago the newly married Ted Lytwyn and Cara Corbo set out to furnish a house. They decided to buy old furniture because it was affordable and sturdy, they liked the way it looked, and, besides, antiques auctions were so much fun. At one country auction they saw some Mission oak furniture and fell in love with it. From that moment they were no longer just a young couple decorating a home — they had become Arts and Crafts furniture collectors. Today Ted is the vice president of the Craftsman Farms Foundation, which manages Stickley's New Jersey home, and Cara is one of the foundation's legal advisers. Their house in suburban New Jersey is filled with Stickley and Roycroft furniture. Perhaps their rarest piece is a Stickley sideboard with open shelving on top, which they bought in two parts. They found the shelving in one dealer's shop and decided to buy it, even though they were not sure how they would use half a piece of furniture After a few years of determined looking, they came across the bottom part in another shop. The reuniting of the cop and bottom halves of this sideboard, made about 1902, is a story of perseverance and amazing luck against very long odds the sideboard is the only example of this Stickley design known to exist today. Cara and Ted are also avid collectors of Stickley and Roycroft metalwork and American art pottery. Their collection of rare ceramics focuses mostly on unorthodox, small-scale studio potters such as Theophilus Brouwer and William J. Walley. Walley was the archetypal, uncompromising Arts and Crafts potter who did everything by hand, he insisted that "there is more true art in a brick made and burnt by one man than there is in the best piece of molded pottery ever made." Walley was a truly passionate potter, just as Ted Lytwyn and Cara Corbo are truly passionate collectors. "Stake our your turf," Ted advises new collectors, "and go for it!"\ Compilation copyright © 1999 Archetype Press\ Text copyright © 1999 David Cathers

IntroductionGustav Stickley and the Craftsmanship of Life13Stickley StyleOutside - Home Making32"That Plainness Which Is Beauty": The Craftsman house34"Under Fragrant Bowers": Porches, pergolas, and terraces39"That Green Eden": The Craftsman garden40Inside - Craftsman Ideals42"Comfort and Beauty": Living rooms44"Centers of Hospitality and Good Cheer": Dining rooms and kitchens47"Complete and Satisfying": Walls and floors48"Simple, Strong, Comfortable": Craftsman furniture51"According to Principle": Metalwork and lamps52"Homespun Harmony": Fabrics, rugs, and needlework55Continuing the Craftsman TraditionStickley Pure and Simple58The House of Mr. Stickley: At Gustav Stickley's home in Syracuse. New York. a fire ignites the Craftsman idea61Stickley's Rustic Vision: Stickley builds the ultimate log cabin at Craftsman Farms in New Jersey68Family Matters: In Massachusetts, a great-granddaughter safeguards Stickley heirlooms79From the Pages of The Craftsman: A Craftsman house constructed from a Stickley plan enlivens a New York City suburb86How to Build a Bungalow: Ninety years later, a Harvey Ellis bungalow design is finally realized near Chicago90Kindred Spirits: Furniture by the brothers L. & J. G. Stickley fills a house outside Boston96Stickley by Serendipity: A Craftsman bedroom in northern California spurs a love of Stickley103A Good Eye for Stickley: Craftsman oak, metalwork, and lighting settle into a stone house near New York City109Hooked on Arts and Crafts: An Arts and Crafts guru disseminates the Stickley gospel115Stickley and Then Some122The First Collector: Robert Judson Clark of California relaunches the Arts and Crafts movement125An Unlikely Setting for Stickley: Stickley treasures complement the author's 1797 farmhouse in suburban New York128Comrades in Spirit, Rivals in Style: A master craftsman's own upstate New York home preserves the spirit of Elbert Hubbard's Roycroft134In the Land of "Free-Hand Architecture": A classic California bungalow showcases the state's exceptional Arts and Crafts achievements141Craftsmen of a Different Stripe: Indian blankets and photographs document a lost way of life153One True Passion: Two halves of a rare Stickley sideboard are reunited by determined collectors in suburban New Jersey156Meeting of the Minds: Then and now, a Greene and Greene landmark in Pasadena makes a perfect fit with Stickley160A Generous Welcome for Stickley: Craftsman ideas find a surprising home in a Texas Victorian171A Harmony of Opposites: Light and heavy, plain and fancy mix as Stickley might have liked179The Wright Kind of House: Spindled splendors by Stickley mirror Frank Lloyd Wright's own principles184Transatlantic Bungalow: A California bungalow pays homage to the international roots of Arts and Crafts191Stickley at HomeCatalogue200Suppliers218Credits219Sources and Further Reading220Index222

\ Ann PrichardThis book is an excellent viewing and source book, providing photographic entree to some of the country's finest Stickley collections. A new book on Stickley's work and philosophy is sure to make a perfect gift for his fans. \ — USA Today\ \ \ \ \ BooknewsText and vivid color photographs explore the central role furniture- maker Stickley played in the development of Arts and Crafts design. Cathers, a writer and lecturer on the Arts and Crafts movement, begins by describing the Craftsman idea and Stickley's vision, then provides an insider's tour of some of the country's most important collections and interiors<-->including Stickley's own home. An extensive catalogue is included for those who want to furnish their own homes with appropriate reproductions. Oversize: 11.25x9.25<">. Annotation c. Book News, Inc., Portland, OR (booknews.com)\ \