Sweet Honey, Bitter Lemons: Travels in Sicily on a Vespa

Replete with authentic Siclian recipes culled directly from the out of the way island stoves and cafe kitchens that cook them, Sweet Honey, Bitter Lemons presents a travelogue for seasoned travelers, and lovers of all things Italian.\ At the age of twenty-six Matthew Fort first visited the island of Sicily. He and his brother arrived in 1973 expecting sun, sea and good food, but they were totally unprepared for the lifelong effect of this most extraordinary place.\ Thirty years later and a...

Search in google:

Replete with authentic Siclian recipes culled directly from the out of the way island stoves and cafe kitchens that cook them, Sweet Honey, Bitter Lemons presents a travelogue for seasoned travelers, and lovers of all things Italian. At the age of twenty-six Matthew Fort first visited the island of Sicily. He and his brother arrived in 1973 expecting sun, sea and good food, but they were totally unprepared for the lifelong effect of this most extraordinary place. Thirty years later and a bit wiser—but no less hungry—Matthew finally returns. Travelling around the island on his scooter, Monica, he samples exquisite antipasti in rundown villages and delicate pastries in towns tumbling down vertical hillsides, and goes fishing for anchovies underneath a sky scattered with stars. Once again this enigmatic island casts its spell as Matthew rediscovers its beauty, the intensity of its flavors, and finds himself digging into the darkness of Sicily’s past as well as some mysteries of his own. Sheila Kasperek - Library Journal A food writer for the Guardian and a judge on the BBC Two (UK) show Great British Menu, Fort adds yet another travelog to the "visit Italy and bask in its gustatory delights" genre made popular by Frances Mayes's Under the Tuscan Sun. Fort explores the food, people, and culture of Sicily, often with comparisons to his experiences on the Italian mainland. As is typical with this genre, the author considers the history of the food he eats and the local way of life as well as the role of community and family in the meals and regional dishes. The narrative is accompanied by numerous recipes (using metric measurements), many of which contain ingredients that may be difficult to obtain outside of Italy. This book partners well with Fort's earlier Eating Up Italy, in which he covers the Italian mainland in a similar manner. There is a sufficient number of books in this genre, making Fort's latest useful only in its exclusive focus on Sicily.

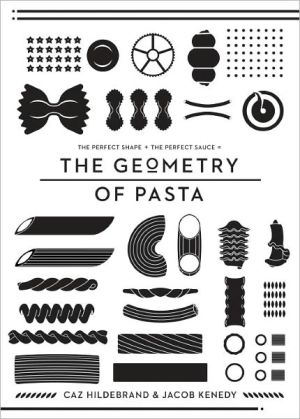

CHAPTER ONE\ Time Present and Time Past\ Marsala\ In 1973 Tom and I had travelled in breezy innocence, with easy optimism and careless curiosity, stopping where we felt inclined. The one introduction we had been given was addressed to Manfred Whitaker, who lived in the Villa Ingham just outside Marsala. Instructions as to how we could find him were hazy in the extreme. Indeed, there was something slightly makeshift about the introduction itself, but we felt that we had better call in out of courtesy, if nothing else, and so we did.\ Manfred turned out to be a stocky, energetic figure, and vigorously, if not rampantly, homosexual. When he saw two strapping lads getting out of their hire car he evidently thought that Christmas had come, a point on which we had to disabuse him rapidly. With the foreplay out of the way, he became the most delightful, charming and obliging of hosts, learned, funny, acerbic and individual. Sadly, I kept no record of his views or our conversations, but I can still sense the mercurial force of his personality, his endless kindness and high good humour.\ I remember being told, probably by Manfred himself, that the Villa Ingham had been built, and its extensive gardens laid out, by a member of the wealthy Ingham family for the delight of his mistress. It didn’t look like my idea of a love nest. It remained in my memory as a large, sober-looking building with an apparently endless sequence of crepuscular rooms, full of shadows and cool air and an accumulation of heavy-gravity, dark-shaded, plumply stuffed Victorian furniture, books, portraits of distinguished ancestors and a random and eccentric cluster of objects, which included a standard lamp made from a stuffed anaconda rearing to its full height. There was Manfred’s throne-like lavatory and the plumbing that had a will of its own. It didn’t strike me as being a grand house, but it did have a certain seriousness about it, a seriousness which Manfred belied.\ He died in 1977 and the house passed to his nephew, William Richards, and his wife Val, who greeted me as I buzzed up the drive in time for lunch. William was a lawyer, successful, jovial, kindly and generous. The Villa Ingham was now a family holiday home, he said. They had thought of selling it at first; it needed so much attention, and Marsala wasn’t exactly convenient. And then they decided they couldn’t. The family loved it too much. Their children came and went, and other family members, too. And yes, they had done a good deal to the house, attended to the plumbing for one thing, and sorted out the kitchen, and turned the water tank above the house into a swimming pool.\ I wandered around the rooms and couldn’t tell what had changed over the intervening years. The furniture seemed the same, the books, the steadfast pictures, the clutter of knick-knacks, and, oh yes, there was the anaconda standard lamp. More than that, the spirit of the place was still the same, that curious combination of the serious and the fantastical, of Victorian worthiness and pagan hedonism, one room leading to the next and to the next and to the next – like some Borgesian metaphysical structure, the crepuscular cool made more crepuscular and cooler in contrast to the brilliantly lit landscape below, where olive and orange trees had been planted in neat rectangular plantations. I didn’t remember the paintings in the manner of Rex Whistler on the high ceiling in the sitting room, and, indeed, it turned out they had been painted by a young friend of the family only a few years earlier, but even they had been absorbed into the patina of the house so that they looked as if they had always been there.\ The garden, too, retained its rambling charm. It had seemed deliciously dilapidated to me 33 years earlier. It did so now. Paths, strewn with withered leaves that crackled explosively underfoot, wove their way between trees and shrubs of luxurious splendour, to crumbling flights of steps leading to another sun and shadow dappled level. Scents rose up where the hot sun struck the shrubs, peppery, pungent, spicy, herbal; thyme, rosemary, clove, aniseed.\ Here was a statue of some antique dryad lurking at the end of a gravel cul-de-sac, peering from a bower of acanthus leaves. Here was a stone trough with lily pads and reflections. Here was a water tank without any water, a line of curious majolica miniature obelisks the colour of the sky ranged along the top of one side. A scuttling in the bushes reminded me of the peacocks that had nested in the trees all those years ago.\ ‘The peacocks are still here,’ said William. ‘There are only two left now, both males. We introduced a couple of females a few years ago in the hope they might breed, but we found them dead a few days later. It seems that the males didn’t appreciate them very much.’ I wondered what might have happened if Adam had taken a similar attitude to Eve in the Garden of Eden.\ The sense of timelessness, of social continuum, carried over into lunch. There were other friends and members of the family staying, too, just as there had been in Manfred’s time, and we sat outside at a table big enough to seat 20 under an awning, shaded from the hot sun. There were only nine of us, but conversation, erudite, funny, discursive, generous, never flagged for a moment. We talked about food and TV chefs in disrespectful terms that Manfred would have approved of, and George Borrow, and the problems of photographing food, and the group of Surrey pensioners who came to pick the olives every year, and Manfred’s idiosyncrasies, and the changes at the Villa Ingham. If I wasn’t quite same figure who had sat in this same place all those years ago, nevertheless there was enough of my young self left to catch the sweet echo of the past.\ We ate panelle, Sicilian fritters made from chickpea flour, bought in the market that morning, and olives from the Richards’ olive trees, and then salami and prosciutto and salad and bread and cheese and fruit, and finished with a granita made from oranges that grew on the estate. There was nothing fancy about any of it, except its quality, the exactness and clarity of flavours. ‘What else did you want?’ I thought, as I sank another glass of chilled rosato, crisp and fresh as ice melt. Not much. Nothing in fact.\ Revisiting the past can be a tricky business. Too often it seems shrunken or down at heel or at odds with the mellowness of memory, but in this case I could feel no difference between past and present. Even Manfred seemed to be about the place, even if I couldn’t quite see him.\ I woke to the smell of the sea, a soup of sharp iodine, seaweed, salt, marine life, sunlight, wind. Marsala is defined by the sea. The sea sits on three sides of it. From the sea came the Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Spaniards, British, Americans, each of the peoples that made and marked it, the fish and trade that fed it. Across the sea went the wine that gave Marsala its last great, rich incarnation a hundred and fifty years ago.\ In 1773 John Woodhouse came to Marsala from Liverpool looking for ingredients for soap. He found the fortified local hooch instead, and decided marsala was the very thing to become smart society’s tipple of choice. The business was given a shot in the arm when Admiral Horatio Nelson ordered several pipes of the stuff for his sailors after the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Over the following century colossal fortunes were made out of the wine. The English connection flourished as the Woodhouse family embraced the Inghams and the Whitakers, the ‘Princes under the Volcano’ as the marsala families were known. Sicilian families, too, joined in the fun, one family in particular, the Florios, becoming the richest and grandest of them all. Each went on to make marked contributions to the cultural life of the island and to the gaiety of nations in general (during Prohibition in America, marsala was classified as a medicinal tonic, and sold as such).\ And then the eminence of marsala began to decline as the founding families sold out to the big commercial battalions; the wine became debased as corners were cut, quality sacrificed to price, and industrial production methods took their toll. As Harry Morley, a determined traveller and devoted classicist, had written as early as 1926: ‘The only good thing you can say about Marsala is that it goes well with gorgonzola. At best it is a poor substitute for sherry or madeira, without any real character of its own.’ The consequences were inevitable. People stopped drinking marsala. Ah, marsala, they said, fine for cooking, but for sipping? And they reached for their glasses of chardonnay.\ The long seafront of the town was lined with the husks of the great bagli, walled, fortified compounds, where the marsala had once been made and stored, and from which it had been shipped across the globe — monuments now to the fall of the great marsala families. Most were derelict, dumping grounds or storage depots for building materials and the like. Dust and plastic bags and bits of paper and dead leaves blew about the courtyards. The three-storey Whitaker baglio had been one of the greatest, with its shaded, arcaded ground floor, Corinthian pillars above, and elegant, shuttered windows on the top floor. Now the golden stucco was fading, stonework crumbling. The shutters sagged on their hinges and the Corinthian pillars held up – what? A vanished history? Not quite.\ Life was beginning to stir in the some of the bagli once more. Marsala was staging a comeback. Its renaissance had begun when a talented winemaker, Marco de Bortoli, decided that redemption lay in quality not quantity, and set about re-creating the wine to new standards. The Buffa family, with one or two others, had joined him, and, little by little, marsala’s reputation was improving. What was it Edward Lear had written?\ He sits in a beautiful parlour\ With hundreds of books on the wall;\ He drinks a great deal of Marsala,\ But never gets tipsy at all.\ Lear can never have come across the Buffa marsala, that’s all I can say.\ As I said goodbye to Domenico Buffa, a stiff wind stirred up the dust in the courtyard of the baglio. Sharp waves flicked the scrubby coastline on to which the building faced, and against the hulls of leisure craft in the marina, against the jetties, against the hulls of the fishing boats – smaller, multicoloured inshore boats; larger, grubbier, more purposeful deep-water boats with names like Turridu, Carmelo and Pinturicchio — moored within the long sheltering arm of the mole that formed the harbour wall.\ I found their harvest in the compact, cruciform fish market just by the Porta Garibaldi, the gate through which Garibaldi entered the town in May 1860 to begin his conquest of the island and start the process that led, with extraordinary rapidity, to the unification of Italy within two years. The Porta Garibaldi was not always the Porta Garibaldi. It had formerly been the Porta di Mare, but history has always marched through and over Marsala. It had been Lilybeaum to the Carthaginians and Marsa Ali, the Port of Allah, to the Saracens. The gate had been built to mimic a Roman triumphal arch. The eagle on it was the emblem of Spanish royalty, from the time when Sicily was part of the Spanish Empire. But the fish and the fishermen have always been there.\ The market may not have been as vigorous as it was once, to judge by the areas not occupied by stalls, but it still supported 15 or so fishmongers, three greengrocers and a salumeria where I could have bought bottarga and strattu, ultra concentrated tomato paste, pecorino and salted anchovies in great round tins. There were a couple of butchers, too, decked out with skinned sheep’s heads that peered with bloody melancholy from the display cabinets.\ It was spring – this was May – and the sloping display counters were crowded with cephalopods: octopuses in four sizes; tiny moscardini like dominoes; squid, flaccid and startlingly white; plump, speckled cuttlefish; and fish – whiting, hake, bream, anchovies, dogfish, gurnard, sea bass in all their shimmering, glittering, scaly glory. Above all, this was the season for pesce spada — swordfish – with the world’s smallest specimen on display, its bill pointing skywards; and for tuna. Each stall had its display, gunmetal skin, round surprised eye in head shaped like a howitzer shell, barrel torso slashed in half presenting a lambent, burgundy surface to the world. And in front six, seven, eight different cuts, ranging in colour from coral pink to a deep, purplish damask.\ According to Alan Davidson in his encyclopaedic classic Mediterranean Seafood, there are several members of the tuna family: bluefin – tonno; albacore —alalonga; little tuna— tonnetto; skipjack – tonnetto listato; and frigate mackerel – tombarello. Of these, the bluefin tuna, the largest, is the most highly prized.\ Traditionally these were taken at the mattanza, the annual ritual in which migrating tuna were herded into nets and then gaffed and slaughtered in a bloody frenzy, just off Favignana, one of the Egadi islands visible from Marsala. The ritual is as old as history. Aeschylus likened the slaughter of the Persians at the Battle of Salamis to the mattanza. Modern historians gave the same name to the ferocious Mafia war that raged between 1970 and 1983, which saw the Corleonesi families rise to control the island’s criminal activities.\ The old mattanza still went on, said Salvatore, a large, genial fishmonger with a shaven head and unshaven chin, but it was not what it once was. For all its picturesque brutality, it was, in fact, an environmentally sustainable way to catch fish. More tuna escaped than were taken, and, before more functional modern methods came along, the mattanza ensured a healthy supply of fish for each season. These days the future of the Mediterranean tuna is debated in the same lugubrious tones we use when considering North Sea cod. It is the appetite for this splendid fish in the rest of the world that is threatening its future. Not that there seemed to be any shortage in the market in Marsala.\ ‘This is good for ragù,’ explained Salvatore. ‘This for brasato, con cipolle e aceto. This you cook ai ferri, grilled. And this in padella al limone.’\ They all looked much the same to me.\ ‘And this?’ I asked, pointing at a piece of tuna the size and thickness of a steak, with thick, creamy seams of fat running between the stratas of purple flesh.\ ‘Ventresca,’ he said, and pointed to his ribs. I understood. It’s the tuna equivalent of belly of pork, the richest part of the fish. Later I ate a thick steak of ventresca a padella, roasted in a pan, in the Trattoria da Pippo; in a stubby backstreet, it was as functional an eatery as I have come across in some time. But the fish was immaculately cooked, crusted outside, its oily richness spreading over my mouth, its roof, sides, nooks, crannies, coating my tongue and throat – a fatness more extreme than mutton, pig or beef fat, but with a bit of beef and lamb about it. This was the true fatness of the sea, the fatness all the sea creatures on which the tuna had been feeding.\ The Via dei Mille runs from the Porta Garibaldi and the market down to the Piazza della Repubblica, the hub of the town. It was down this road that Garibaldi led his ragtag and bobtail thousand in 1860 at the beginning of the campaign that resulted in the unification of Italy.\ ‘Ma per me, Garibaldi non era un eroe – Garibaldi wasn’t a hero as far as I’m concerned,’ said my guide and mentor Nanni Cucchiara, a civilised and cultured man, lawyer and gourmet, with a round face shaded by a three-day stubble, wary, clever, dark eyes and unruly black hair. He was, by turns, perceptive, subtle, expressive and generous with his knowledge, but guarded with himself. It was as if he was always gauging what I had meant by what I said, or whether I had really meant what I said, or if there was some other layer of meaning to my words. Or it may have been he just had trouble understanding my Italian.\ ‘Garibaldi had always been a republican, but he sold out to the king and the interests of the north,’ Nanni said. He went on: ‘When he came to Sicily, Garibaldi acted like a dictator. He removed the old structures but did not replace them with anything better. Sicily became a lawless place as a result. It is interesting that the banditry and the Mafia, that have been so difficult for Sicily, only developed after the unification of Italy. Since then we have added Piedmontese exploitation and corruption to the exploitation and corruption of our own.’\ We were standing in the Piazza della Repubblica. The old centre of Marsala had a curious air to it, antique and pristine at the same time, having been scrupulously rebuilt after the Second World War. I was particularly taken with the ingenious system for keeping the main streets clean. Sunken culverts ran down the edge of the streets, tucked beneath an overhanging lip of pavement. Any rubbish at street level was brushed into these, hidden from sight and then flushed away at regular intervals.\ One side of the piazza was dominated by a handsome cathedral dedicated to St Thomas à Becket. Thomas à Becket? Not the English archbishop murdered by the thanes of Henry II? The very same. Marsala seemed an odd place for him to crop up, for I had always thought of him as a very British figure. On the opposite side of the piazza was the Caffetteria Grand’ Italia, a handsome place run with the cheery professionalism that seems commonplace in Italy. Service was sharp, leavened by free and easy banter with the regulars, and the flow of coffees, made to a uniform excellence that would be remarkable in Britain, crisp. The coffees were buttressed by cornetti con crema, gloriously crunchy-squidgy croissants stuffed with crème patissiere that would deposit a light fall of icing sugar down my front if I wasn’t careful. I was rarely careful enough. During the early morning, a steady stream of men and women on their way to work stopped in for a cup of dark espresso, a glass of water, a cornetto. One minute, two minutes, three minutes maximum, and they’d drunk, eaten, chatted and gone. But briskness and efficiency didn’t preclude civility.\ ‘But the relationship between the Mafia and Sicilians is very ambiguous, The Mafia is still “respected” in Sicily,’ said Nanni, as he sipped an espresso, picking up the thread of our earlier conversation.\ ‘Respect? What do you mean?’\ ‘It’s difficult to explain to anyone who isn’t Sicilian,’ he said. ‘It’s a kind of understanding, esteem.’\ ‘So will the Mafia ever disappear?’ I asked.\ ‘Everything disappears eventually,’ Nanni said. ‘The Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the Spanish. They all went. In the end.’ Bearing in mind the way the Mafia had assassinated Borsellino, ‘his sangfroid seemed remarkable.\ Out in the piazza groups of men moved in a stately quadrille, talking. It seemed curious that in a town so richly endowed with orologerie, watch and clock shops, time was treated as an illimitable resource. No one hurried. Everyone always seemed to have time for a coffee, a pastry, a chat, to exchange pleasantries, discuss politics, haggle over food. Time was spent with a lavishness that contrasted sharply with the way we treat it in Britain. We are, we claim, time poor. Asset rich, but time poor. We never have time to cook, to eat, for our children, for each other, for ourselves. Sicilians might not be asset rich, but they have all these other things.\ That evening Nanni took me to Il Gallo e l’Innamorata, a small restaurant with the lively informality of a bar and some very serious food.\ We started with antipasto: a little stack of neonati — tiny fish, fried crisp like tiny wisps of straws; an octopus salad, muscular and sweet; bruschetta of salty bottarga, dried tuna roe, a concentrate of marine life lightened and made fresh with bouncy tomatoes ‘from Pacchino’; fried fillets of sardine, the flesh firm and flaky, dusted with oregano; and moscardini — diminutive squid. Each dish was characterised by the luminous freshness of the ingredients, by the limpid quality of each flavour. I wiped up the smears of sauce with bread scattered with sesame seeds.\ ‘And now we must have tuna,’ said Nanni. ‘The tuna season starts in May and ends in June. You won’t find any fresh tuna after that. It’ll be frozen. It’s only worth eating when it’s fresh.’\ So we had busiati con ragu di tonno. The tuna in the sauce had melted into a rollicking tomato sauce. This was stiffened with a compound of pan grattato (dried breadcrumbs), olive oil and basil added in place of grated cheese. The precise use of the pan grattato, basil and oil was exactly the kind of small detail that makes a dish sing.\ The busiati – ‘This is the right pasta to have with tuna,’ said Nanni emphatically. ‘You might try a broad, flat pasta, like pappardelle, but this is better’ – looked very like the fileji I had come across in Calabria a few years before: slender coils made by twisting the soft dough around a metal core not unlike a knitting needle, which had been used for the same kinds of fish-based sauce. The busiati were longer than fileji, but the principle was exactly the same. Goethe recorded watching a family making pasta in exactly the same way during his trip to Sicily in 1786.\ ‘We get olive oil from the Greeks,’ explained Nanni, ‘bread from the Romans, sesame seeds, sorbets, rice and pastries from the Arabs, tomatoes and chocolate and our sweet tooth from the Spaniards.\ ‘We may take their food,’ he went on,‘but all the foreigners who come to govern Sicily end up by becoming Sicilians – Greeks, Romans, Arabs, French, Germans, Spanish. Even you English. There is something about this island.’\ In view of what we had already eaten, we decided to pass on the secondo piatto, and go straight to pudding. I was grateful for this consideration. I was beginning to learn that a Sicilian’s notion of portion control makes the average helping in Yorkshire seem like an offering from WeightWatchers.\ Pudding was cappidduzzu. ‘Or cassatedda as it is known in Trapani. Or raviola in Mazara del Vallo,’ explained Nanni. I said that didn’t explain anything, and just made matters very difficult for us foreigners. Cappidduzzu or cassatedda or raviola turned out to be golden-brown crunchy raviolo stuffed with sweetened sheep’s ricotta. It came with a white mound of almond ice cream complete with shards of almond.\ Replete and cheerful, we made our way back through the darkened, deserted streets. We paused at the top of the lane leading to my hotel. A stiff wind blew, sending the odd scrap of paper scurrying down the street. I would be leaving the next day. I thanked Nanni for his time and generosity. It had been his pleasure, he said.\ There was an affinity between Sicilians and the English, he went on. ‘We are both eccentric people,’ he said. ‘Eccentric in the original meaning of the word. We live away from the centre - ex centro to give the Latin origin. We are island peoples. We resist any centralising process that tries to make us all behave in the same way.’\ We shook hands and parted. I pondered on his observation. I wasn’t so sure I could see the similarities. Sicilians had murderous vendettas spanning decades. We had leylandii hedge feuds.\ Panelle\ You find panelle all over Sicily, although it’s claimed that they are native to Palermo. That might have been true once upon a time. Unquestionably they are a Moorish nibble, not unlike fatayer bi hummus from the Lebanon. There’s not really a secret authentic recipe. To be honest, this is an amalgam of several I was given.\ Makes about 20 panelle\ Salt • 500g chickpea flour • 2 tbsp chopped broad-leafed parsley • Freshly ground black pepper • Vegetable oil\ Bring 21 water to a gentle boil and lightly salt. Add the chickpea flour a little at a time, stirring to make sure the mixture is smooth. Always stir in the same direction. Add the chopped parsley and season with black pepper. Go on cooking until you have a smooth paste that begins to pull away from the sides of the pan. Turn out onto an oiled surface and smooth out until it’s about 0.5cm thick. Allow to cool. Cut into little rectangles. Heat vegetable oil in a pan and fry a few of the rectangles at a time until pale golden brown. Drain on a kitchen towel and eat while still warm.\ Granite d’arancia di Racalia\ A delightful refresher from that memorable lunch at the Villa Ingham, a.k.a. Racalia.\ Serves 6\ 150g granulated sugar • Juice of 8 freshly squeezed Tarocco oranges • Juice of I lemon\ Put 250ml water and the granulated sugar into a saucepan. Heat until the sugar has dissolved and then boil for at least a minute. Allow it to cool completely. Add the orange and lemon juices. Transfer the mixture into a plastic container and pop the container into a freezer. Leave for 2 hours, stirring with fork every 10-15 minutes. The granules should be fine, almost mushy by the end.\ Tonno con cipolle e aceto\ Serves 4\ 600g tuna • Olive oil • Flour seasoned with salt • 2 large onions • 1 tbsp sugar • 50ml red wine vinegar • 25g chopped mint\ Wash the tuna and cut into thickish slices, maybe 1cm thick. Pat dry. Heat the oil in a frying pan. Dip each tuna slice in the seasoned flour and fry quickly for 1-2 minutes on each side until they are golden-brown. Leave to drain on kitchen towel. Peel and slice the onions very finely. Fry in the same oil used to cook the tuna. Add a tablespoonful or so of water and cook over a very low heat for about an hour. Add the sugar and sprinkle the red wine vinegar and the mint. Leave to cook for a further couple of minutes. Place the tuna on a plate, pour the sweet and sour onion mixture over them and leave to cool for a few hours.\ Busiati con ragù di tonno\ Serves 4\ 1kg tuna • 1—2 garlic cloves • Dried oregano • Extra virgin olive oil • 1 onion • 3—4 very ripe tomatoes • 2 dsp strattu (very concentrated tomato purée) • 3 tbsp red wine • 1 dsp red wine vinegar • 1 clove • Salt and pepper • 600g busiati or pasta of a similar class (eg bucatini or maccheroncini)\ Wash and dry the tuna and cut into chunks. Peel and cut the garlic into slivers. Stick a sliver of garlic into each tuna chunk, along with a pinch of dried oregano. Put a dash of oil into a frying pan and fry the tuna until golden-brown all over. Drain on kitchen towel. Slice the onion thinly and peel, seed and chop the tomatoes. In another pan fry the onion in a little more oil until golden. Add strattu plus the wine and vinegar. Cook over a low heat for a minute or two. Add the tomatoes. Cook for 20 minutes over a low heat. Add the tuna chunks and the clove. Cook over a very low heat for an hour or so, until the sauce has become quite concentrated. Add salt and pepper according to your taste. Meanwhile, cook the pasta in boiling salted water until al dente. Serve it with the sauce.\ Cappidduzzu\ Makes about 25 cappidduzzu\ Olive oil • Ground cinnamon • Caster sugar\ Pastry: 750g flour • 30g caster sugar • 250ml white wine • 70g sugna (pig fat)\ Filling: 750g ricotta • 300g caster sugar • Grated rind of a lemon\ Sift the flour and sugar together. Make a well in the middle. Add enough of the wine to make a stiffish dough. Add the fat in small pieces, kneading it well into the dough. Knead for 15-20 minutes until you have a smooth, silky dough, stretching it out and folding it over to incorporate as much air as possible. Place the dough in a bowl, cover with a kitchen towel and let it rest in a cool place for an hour or two.\ Pass the ricotta through a sieve. Beat in the sugar. Pass it through a sieve again. Stir in the lemon peel.\ Roll out the dough into a very thin sheet. Cut out circles approximately 8cm across. Plop a 1½ dsp of the ricotta mixture on one side of each circle, and fold the dough over into halfmoons, wetting the edges and pressing them together to get a complete seal.\ Heat the olive oil until very hot. Fry each cappidduzzu until golden-brown. Drain on kitchen towel. Sprinkle with a little ground cinnamon and caster sugar. Serve warm.\ Carmelo & Giovanni Pomella, Macelleria degli Fratelli Pomella, Corleone\ SWEET HONEY, BITTER LEMONS. Copyright © 2008 by Matthew Fort. All rights reserved. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

\ Library JournalA food writer for the Guardian and a judge on the BBC Two (UK) show Great British Menu, Fort adds yet another travelog to the "visit Italy and bask in its gustatory delights" genre made popular by Frances Mayes's Under the Tuscan Sun. Fort explores the food, people, and culture of Sicily, often with comparisons to his experiences on the Italian mainland. As is typical with this genre, the author considers the history of the food he eats and the local way of life as well as the role of community and family in the meals and regional dishes. The narrative is accompanied by numerous recipes (using metric measurements), many of which contain ingredients that may be difficult to obtain outside of Italy. This book partners well with Fort's earlier Eating Up Italy, in which he covers the Italian mainland in a similar manner. There is a sufficient number of books in this genre, making Fort's latest useful only in its exclusive focus on Sicily.\ —Sheila Kasperek\ \ \