The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition

In this masterful work of historical scholarship, Zeev Sternhell, an internationally renowned Israeli political scientist and historian, presents a controversial new view of the fall of democracy and the rise of radical nationalism in the twentieth century. Sternhell locates their origins in the eighteenth century with the advent of the Anti-Enlightenment, far earlier than most historians.\ \ The thinkers belonging to the Anti-Enlightenment (a movement originally identified by...

Search in google:

In this masterful work of historical scholarship, Zeev Sternhell, an internationally renowned Israeli political scientist and historian, presents a controversial new view of the fall of democracy and the rise of radical nationalism in the twentieth century. Sternhell locates their origins in the eighteenth century with the advent of the Anti-Enlightenment, far earlier than most historians. The thinkers belonging to the Anti-Enlightenment (a movement originally identified by Friederich Nietzsche) represent a perspective that is antirational and that rejects the principles of natural law and the rights of man. Sternhell asserts that the Anti-Enlightenment was a development separate from the Enlightenment and sees the two traditions as evolving parallel to one another over time. He contends that J. G. Herder and Edmund Burke are among the real founders of the Anti-Enlightenment and shows how that school undermined the very foundations of modern liberalism, finally contributing to the development of fascism that culminated in the European catastrophes of the twentieth century.

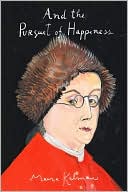

The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition\ \ By ZEEV STERNHELL \ Yale University Press\ Copyright © 2010 Yale University\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-300-13554-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ The Clash of Traditions \ In order to embrace in all its fullness and complexity the significance of the campaign against the English and French Enlightenments for the world of our time, one has to begin by going back to the late seventeenth century. The triumph of the moderns in the famous Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, which began in 1687, just when England was preparing the Glorious Revolution, was the first success of the Enlightenment. The second victory of the new values was the establishment of the new English regime.\ Both intellectually and politically, the whole significance of the Glorious Revolution was expressed in Locke's Two Treatises. At a time when England was changing its regime rapidly and without resistance or bloodshed, France, at the end of the reign of Louis XIV, was only able to embark on a long and difficult intellectual battle. This tremendous difference between the situation in the two countries left a lasting imprint on the French Enlightenment, and from the end of the eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century people spoke of a conflict of civilizations. In the political and social context that existed in France throughout the eighteenth century, the awareness of theinjustices and malpractices of the situation at the time, the struggle against authoritarianism, the struggle for liberty and for the right of people to free themselves from the shackles of the past, took the form of a violent cultural and ideological campaign.\ The rejection of what existed gave rise to an unprecedented upsurge of historical thinking: never had the world of the future been debated so intensively. People thought about the past but did not bow down to its authority, or to that of the present; and if they did not bow down to the present, it was because they were convinced they had the right and the capacity to mold the future. "We are now got at the origin of Man, and at the origin of his rights. As to the manner in which the world has been governed from that day to this, it is no farther any concern of ours than to make a proper use of the errors or the improvements which the history of it presents," wrote Thomas Paine in his famous refutation of Burke's Reflections. "Those who lived an hundred or a thousand years ago, were the moderns, as we are now. They had their ancients, and those ancients had others, and we shall also be ancients in our turn.... The fact is, that portions of antiquity, by proving everything, establish nothing. It is authority against authority all the way, till we come to the divine origin of the rights of man at the creation."\ Contrary to an idea promoted by the first enemies of the Enlightenment, which the nineteenth century did not fail to adopt, the age of Voltaire, Gibbon, and Hume was the real beginning of modern historiography. Historiography only became possible with the beginnings of criticism, and criticism is only possible when one affirms one's autonomy. Historiography only becomes a form of intellectual activity when one ceases to look for the divine will in history and entrusts oneself to the power of reasoning in order to understand the past and prepare for the future.\ Criticism of the existing political order, but also criticism of morals, religion, law, and history, from the point of view of reason is the distinctive feature of the Enlightenment. Kant knew this, and Cassirer and Husserl made a point of praising reason at a critical juncture in the history of their age. A comprehensive critique of what exists marks the entrance to rationalist modernity. It was in the last years of the seventeenth century that modernity began to appear as a radical break with the past (antiquity), and above all with its accepted models. With the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, there was an extraordinary, almost unprecedented break that sanctioned the rebellion, innovation, and criticism associated with the idea of modernity. The controversy that arose at the turn of the eighteenth century was the last in a long series of reflections on the antiqui and the moderni whose beginnings went back to Cassiodorus, historian of Theodore the Great, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. From the twelfth century to the eighteenth, the debate on modernity never stopped. This was because the idea of modernity, as Jürgen Habermas has shown, reappears each time people in Europe are conscious of beginning a new period: "The modern world is distinguished from the old by the fact that it opens itself to the future, the epochal new beginning is rendered constant with each moment that gives birth to the new." The school of Chartres, with Bernard of Chartres and John of Salisbury, put forward the idea that the ancients were "giants" and the modern "dwarfs" stood on their shoulders, but, thanks to their position, the modern "dwarfs" saw farther than the ancients. In the sixteenth century, there were two clearly opposing sides to the debate: with Rabelais, Giordano Bruno, Jean Bodin, and Francis Bacon at the beginning of the following century, the moderns were no longer afraid to assert their superiority.\ On the other side was the camp of the ancients. In a fine chapter in his Essays, rightly called "Of Custom and Not Easily Changing an Accepted Law," Montaigne, after giving the great names of antiquity from Socrates and Plato to Octavian and Cato, declared, "I have a great aversion to novelty, whatever its appearance, and in this I am right, for I have seen the harmful results it can have.... Even the best pretext for modernity is very dangerous: adeo nihil motum ex antiquo probabile est."\ In the mid-seventeenth century, Blaise Pascal adopted a compromise position in what seems to have been a last attempt to save whatever could be saved of the authority of the ancients. This difficult balance became hard to maintain, however, as an increasing number of Europeans came to the conclusion that the masterworks of Pierre Corneille, Jean Racine, and Molière, Nicolas Poussin, Charles Le Brun, and Claude Perrault were something quite different from an imitation of the great writers of ancient times. In many ways, the age of Louis XIV was not inferior to the age of Augustus. On January 27, 1687, at the Académie française, Charles Perrault recited a famous poem on the age of Louis the Great, which he compared advantageously to antiquity. The celebrated Quarrel raged on until it ended, a quarter of a century later, with Fénélon's Lettre à l'Académie. In 1715, on the eve of his death, Fénélon put an end to what he called "the dispute" and even "the civil war of the Académie": "I do not exalt the Ancients as models without imperfection: I do not wish to take from anyone the hope of overcoming them. I hope, on the contrary, to see the Moderns victorious through the study of the very Ancients they will have overcome." Indeed, in its underlying implications, the "Letter to the Academy" has a far more modern and progressive character than the counterrevolutionary pamphlets of the end of the century. Far from blindly worshipping the genius of antiquity, Fénélon did not hesitate to praise his contemporaries fulsomely: "One must admit that there are few excellent writers among the Ancients, while among the Moderns there are some, whose works are precious." Not only does the archbishop of Cambrai not fail to point out the weaknesses and faults of the ancients, particularly in philosophy, he notes the cultural and historical difficulties the modern reader has in studying the work of the ancients. He thus asserts not only the right to innovate but also a continuous forward movement, based on the progress of the human spirit and the independence of each generation. Moreover, Fénélon has a very rationalist and modern sense of the superiority of his age, "which has only just emerged from barbarism." A few pages earlier, he said that the Franks of Clovis's time were "a fierce band of wanderers, and if one can perceive a ray of politeness coming to birth in Charlemagne's empire ... the immediate fall of his house plunged Europe once again into a terrible barbarism. Saint Louis was a prodigy of reason and virtue in an age of iron. We have only just emerged from this long night."\ That was how Enlightened modernity gained respectability and the idea of linear progress came to be accepted. The present was conceived as infinitely superior to the immediate past and did not have any complexes concerning the greatness of antiquity. Already the superiority of the present began to be clearly asserted. The cult of the Middle Ages that appeared at the beginning of the eighteenth century with Vico and at the end of the century with Herder, and was much developed by the early Romantics, was in no way a type of return to faith or the rediscovery of a brilliant lost civilization, but solely a revolt against the Enlightenment. The fact that this veneration of a vanished world began with Vico and Herder is not surprising. In some ways, the Augustinian Fénélon, author of the famous Démonstration de l'existence de Dieu (Demonstration of the Existence of God), writing at the turn of the eighteenth century, was closer to the great "pagans" of the French Enlightenment than to their enemies, Vico, Johann Georg Hamann, Herder, Burke, and de Maistre, pillars of the faith and the established church.\ The Letter also has another interesting aspect. Its author hoped that the Académie "would get us a treatise on history." Fénélon considered history a key discipline, an incomparable tool "that uncovers origins, and explains how peoples passed from one form of government to another." But in order to write history, he said, one needed good historians. A good historian would devote himself particularly to "depicting the main characters and discovering the causes of events." He would show objectivity, a critical sense, curiosity, would not be blinded by patriotism, would present the facts without taking sides, and would not be swayed by the prevailing opinion ("he would follow his tastes without taking account of those of the public").\ A good historian would not be guilty of anachronism and would not be guided by the discovery of innumerable "small facts": one should leave "this superstitious exactitude to compilers." He would not be "a dry, sad writer of chronicles," who could only produce "a history chopped up in small pieces, so to speak, without any living thread of narrative." Against this, a historian worthy of the name would reconstruct "the exact form of government and the details of the manners and customs of the nation whose history he is writing, in each period." This is where one must show exactitude: in depicting periods, systems of government, ways of thinking, and social structures, for-this is certainly what Fénélon meant, and it was a lesson that was learned by Voltaire -"each nation has very different customs from those of the neighboring peoples. Each people often changes its own customs." Here is also the origin of the famous discoveries usually ascribed to Herder. Fénélon considered a good historian to be like a good painter: "The principal perfection of a history lies in its order and arrangement. In order to achieve this exemplary order, the historian must embrace and possess the whole of his history. He must see it in its entirety, as though at a single glance. He must be able to look at it from every angle until he finds his true viewpoint. He must demonstrate its unity, and draw from a single source, so to speak, the principal events that depend on it." A demanding reader, Fénélon ended with a concise but concentrated critique of the great historians of antiquity: Herodotus, Xenophon, Polybius, Thucydides, Sallust, Tacitus, all of whom, he said, had their faults, often major faults. It only remained for the reader to draw his own conclusions: the world moves ahead, and the future belongs to the moderns.\ The scientific and intellectual revolution that took place in the seventeenth century, which ensured the victory of the moderns and whose last stage happened in these years of "crisis of the European consciousness," to use Paul Hazard's felicitous expression, gave birth to an unusual intuition in the history of our civilization: the idea and already the conviction that people have the right to build a world different from the one they have inherited. In this way, history lost its function of guardianship. If, as Fénélon thought, the world had only just emerged from barbarism, it could not possibly seek its norms of conduct in the long night from which it had just emerged. As a result, an extraordinary reservoir of intellectual and then political energy was released. Each generation now felt itself free to engage not only in the discovery of the physical universe but also in that of history, of anthropology, of new political and social structures. The individual felt himself to be master of his existence, equal to the most powerful, capable of forging for himself a world that his ancestors could not even dream of. He began by drawing up accounts and speculating on the reasons for the misfortunes that overtook him. This was the famous question that bursts forth at the beginning of the first chapter of the Social Contract, the hundred pages of the Second Discourse where Rousseau considered the origins of civil society, and in so doing produced an extraordinary essay of philosophical anthropology without God. Rousseau, the thinker most hated by the enemies of the Enlightenment, created a history of the origins of humanity that destroyed the religious conception of life. He was the one who eradicated revelation from the life of men, and in the very beginnings of capitalism raised the flag of revolt against social injustices. According to him, the origin of evil was to be found not in human nature but in social structures, and property was the source of the evils in eighteenth-century bourgeois society, where there was no liberty, and inequality prevailed. Contrary to a commonly accepted idea, Rousseau was not a pessimist: if he cannot be counted among the theoreticians of progress, he nevertheless regarded man as master of his destiny. For the people of the Enlightenment, evil resided not in man but in social conditions, ignorance, superstition, and poverty.\ Alain Renaut has brilliantly demonstrated that Rousseau was the first person to have expressed the idea that human liberty reveals itself through man's capacity to free himself from nature, and hence through an absence of definition or essence. One may recall the Sartrian metaphor of the paper cutter as it appears in one of the most famous texts in twentieth-century thought: Existentialism Is a Humanism. In this celebrated lecture, given in 1946, Sartre described the main difference between a human condition and a thing-like condition. He reproached theology and traditional philosophy as having conceived of man as being created on the model of a manufactured object, and of God, correspondingly, as being a kind of skilled craftsman. In this conception of the world, there is no room for human liberty, as man is a prisoner of his nature, of a certain finality or model, which he can no more escape than a paper cutter can. An authentic humanism, on the other hand, is characterized by the idea that "there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being that exists before it can be defined, and that that being is man." Without Sartre being in any way aware of it, said Renaut, putting his finger in this way on a fundamental but little-known and ill-understood aspect of eighteenth-century thought, this phenomenological or existentialist conception of humanism, far from breaking away from the philosophy of the Enlightenment, was entirely in keeping with Kant's and Fichte's ideas on the humanity of man as historicity. These ideas were largely derived from Rousseau.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Anti-Enlightenment Tradition by ZEEV STERNHELL Copyright © 2010 by Yale University. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Introduction 11 The Clash of Traditions 402 The Foundations of a Different Modernity 933 The Revolt against Reason and Natural Rights 1414 The Political Culture of Prejudice 1875 The Law of Inequality and the War on Democracy 2236 The Intellectual Foundations of Nationalism 2747 The Crisis of Civilization, Relativism, and the Death of Universal Values at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century 3158 The Anti-Enlightenment of the Cold War 372Epilogue 422Notes 445Index 516