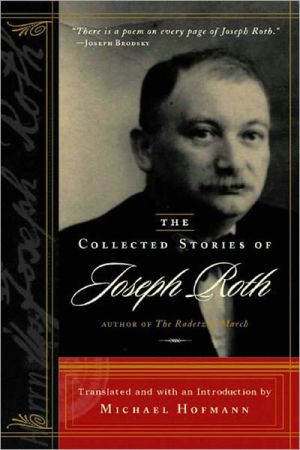

The Collected Stories of Joseph Roth

The Collected Stories, in its variety and force, is the essential introduction to the fiction of Joseph Roth.\ Appearing in English for the first time, The Collected Stories of Joseph Roth includes seventeen novellas and stories that echo the intensity and achievement of his greatest novel, The Radetzky March. Spanning the entire range of Roth's brief life (1894-1939) and showcasing the breadth of his literary powers, this collection features many stories just recently discovered. Roth's...

Search in google:

Roth's novellas and short stories will rank with Chekhov's and Kafka's as among the greatest of modern literature.Nadine GordimerThe totality of Joseph Roth's work is no less than a tragedie humaine achieved in the techniques of modern fiction.

Chapter One \ \ \ THE HONORS STUDENT\ (1916)\ Anton, the son of the postman Andreas Wanzl, was the oddest child you ever saw. His thin, pale little face, with its sharply etched features, emphasized by a grave beak of a nose, was surmounted by an extremely sparse tuft of white blond hair. A lofty brow lorded it over a practically nonexistent pair of eyebrows, below which two pale blue deepset eyes peered earnestly and precociously into the world. A certain stubbornness showed in the narrow, bloodless lips, clamped tight. A fine, regular chin brought the ensemble to an unexpectedly imposing finale. The head was perched on a scrawny neck; the whole body was thin and frail. Altogether incongruous on such a frame were the powerful red hands that looked as though they had been glued on at the delicate wrists. Anton Wanzl was always neatly dressed and in clean clothes. Not a speck of dust on his jacket, no hole, however tiny, in his stockings, no mark or scar on his smooth, pallid little face. Anton Wanzl rarely played, he never got into fights, and he never stole red apples from the neighbor's garden. All Anton Wanzl did was study. He studied from morning till late at night. His textbooks and exercise books were nicely wrapped in crinkly white greaseproof paper, all bearing his name on the cover, written in an oddly small, pleasing hand for a child. His glowing reports, ceremonially folded, were kept in a large brick red envelope next to the album of specially beautiful stamps, for which Anton was even more envied than for his reports.\ Anton Wanzl was the quietest boy in the whole town. Atschool, he sat still, with his arms crossed in the approved fashion, always keeping his precocious little eyes fixed on the teacher's mouth. He was top of the class, naturally. He was always held up to the others as an example; never was there any red ink in his books, with the exception of the mighty A that regularly graced all his work. Anton gave calm, factual answers, he was always there, always prepared, never sick. He sat on his bench at school as though nailed there. The most disagreeable thing for him were the breaks. Then everyone was made to go outside while the classroom was aired, and only the monitor stayed behind. Anton went out in the yard, hugged the wall fearfully, and didn't dare to take a single step, afraid he might get knocked to the ground by one of the noisy, rowdy boys. When the bell rang for resumption of class, Anton breathed a huge sigh of relief. Calmly, headmasterlike, he strode along behind the surging rabble of boys, calmly he took his place beside his bench, didn't say a word to anyone, stood there bolt upright, and sat down mechanically only once the teacher had given the command.\ Anton Wanzl was not a happy child. He was consumed by a burning ambition. An iron desire to shine, to outdo all his comrades, almost destroyed his puny constitution. To begin with, Anton had only one end in mind. He wanted to be a monitor. At that time, this post was occupied by someone else, obviously not such an outstanding pupil, merely the oldest boy in the class, whose venerable years had sufficed to make him, in the eyes of the master, trustworthy. The monitor was a sort of stand-in for the master. He had to watch over his peers, "take the names" of boys who misbehaved and pass them to the master. He was, further, responsible for the state of the blackboard, for the presence of damp sponge and sharp chalk, and he collected the money for exercise books, inkwells, and repairs to cracked plaster and broken windowpanes. Such an office was vastly impressive to little Anton. He spent sleepless nights brooding determined, vengeful plans; he plotted endlessly how he might bring down the monitor and take over the position himself. One day he thought he had found a way.\ The monitor had a weakness for colored pens and pencils, for canaries, doves, and little cakes. Such presents were acceptable bribes, and the giver could go on to make as much noise as he pleased. This was where Anton could take a hand. He never brought presents himself. But there was another boy, who also didn't pay tribute. Since the monitor couldn't denounce Anton because he was above suspicion, this other little boy, poor fellow, was the daily victim of his monitorial denunciations. Anton saw a wonderful opportunity. No one would guess that he wanted to be monitor. So, if he took the poor, beaten boy under his wing, and informed the teacher of the shameful venality of the young tyrant, that could only be termed just, fair, and courageous. And there would be no other candidate for the monitor's post than—Anton. So, one day, he plucked up courage and denounced the monitor. The boy was immediately stripped of his post, given a few blows with the cane, and Anton Wanzl was solemnly appointed in his place. He had made it.\ Anton Wanzl loved sitting on the raised dais at the front. It was such a blissful feeling to look down on the classroom from a dignified height, to wave his pencil self-importantly, to issue warnings in some cases and to play God in others, writing down the names of the oblivious noisemakers, thus delivering them to a condign punishment, knowing in advance the form an implacable fate would take. One was taken into the master's confidence, permitted to carry exercise books, could appear important, enjoyed the awe of one's peers. But Anton Wanzl's ambition was not satisfied. He always had a fresh goal in mind. And it was toward this that he set himself to work as hard as he could.\ He was not by any means a fawner. He kept a veneer of dignity, each one of his little actions was carefully considered, he liked to pay little acts of courtesy to the teachers, but never obsequiously, helping them into their coats, say, but always with a stern expression on his face. Each one of his flatteries was unobtrusive and had something of the character of an official act.\ At home, he was called "Tonerl" and was a figure of some standing. His father was the typical small town postman, half public official, half private secretary, in on all kinds of family secrets, a little bit dignified, a little bit submissive, a little bit proud, and a little bit wanting a tip. He had the typical stooped walk of the postman; he scuffed his feet, he was small and thin like a little tailor, his cap was slightly too big for him and his trousers slightly too long, but all in all he was a "decent fellow," and enjoyed the good opinion of his superiors and the citizens of the town.\ But to his one and only son, Herr Wanzl accorded a degree of respect that he otherwise felt only for the mayor and the Director of the Postal Service. Yes, Herr Wanzl would often think to himself on his Sunday afternoons off: the Director is the Director. But think of what my Anton might one day become! Mayor, secondary school headmaster, alderman, and—at this point Herr Wanzl took a huge leap of faith and imagination—perhaps even Minister? When he expressed such thoughts to his wife, she would dab her eyes with the corners of her blue apron, sigh, and go, "Ah. Ah." For Frau Margarethe Wanzl had an enormous respect for husband and son, and if she set a postman above all others, what could she do with a minister?\ Little Anton paid his parents back for their loving care by being mightily obedient. Admittedly, it wasn't that difficult for him because, as his parents didn't give many orders, Anton didn't have much obeying to do. But just as it was his ambition to be an outstanding pupil, so he desired to be thought of as a "good son." When his mother sang his praises to the assembled neighborhood women on the egg yellow wooden bench outside the door in summer, Anton could feel his heart burst with pride, as he sat out in the hen coop with a book. He took care that his expression remained quite impassive, buried in his book, as though he didn't hear a word of their women's talk. For Anton Wanzl was a diplomat to his fingertips. He was too calculating to be good.\ No, Anton Wanzl was not good. He lacked love, he lacked heart. He did only what he thought was clever and sensible. He gave no love and asked for none. He never needed any affection, any tenderness; he wasn't given to feeling sorry for himself, he never cried. Anton Wanzl didn't even have tears. A good boy wasn't allowed to cry.\ And so Anton Wanzl grew older. Or rather: he grew. Because Anton had never been young.\ Nor did Anton Wanzl change when he was at the Gymnasium. He only became still more careful. He continued to be the scholarship boy, the model pupil, industrious, well behaved, and virtuous, he was equally good at all subjects, he had no so-called favorites because there was nothing in him that was to do with affect or taste anyway. He declaimed Schiller's ballads with verve and pathos, took part in various school productions, and spoke sagely and precociously about love—though he was careful never to fall in love himself, and with girls played the boring role of confidant and pedagogue. But he was an excellent dancer, a sought-after partner at dances and hops, his manners and his boots were exquisitely lacquered; both his trousers and bearing were nicely starched, and his shirt front supplied the purity that was lacking in his character. He always helped his peers, not because he wanted to but because he was afraid he might one day need something from them. He continued to help his teachers into their coats, was always discreetly available when needed, and, in spite of his sickly appearance, was never ill.\ After sailing through his final exams, and the usual round of congratulations and good wishes, the embraces and kisses from his parents, Anton Wanzl paused to think about the direction his future studies should take. Theology! That would have been perfect for him, with his pallid sanctimoniousness. But then again—theology! How easily one might come a cropper there! So, not that. He didn't like his fellow humans enough to be a doctor. He wouldn't have minded becoming a lawyer, especially a prosecutor—but law was vulgar and unidealistic. Philosophy was idealistic. And especially literature. Even if, as people said, there was "nothing you could do with it." But if one went about it the right way, surely it was possible to make one's fortune and one's name. And going about things the right way—that was Anton's specialty.\ So Anton became a student. The world had never seen such a "proper" student. Anton Wanzl didn't smoke, didn't drink, didn't brawl. Of course, he had to belong to a fraternity, that was deeply ingrained in his nature. He needed to have peers whom he could put in the shade, he needed to shine, have a position, hold forth. And even if the other members of the fraternity laughed openly at Anton, called him a lag and a stay-at-home, they were actually rather intimidated by the young person who was only just beginning his studies but already displayed such astonishing learning.\ Anton won respect from the professors as well. That he was clever, they could tell at a glance. He was moreover an extremely useful reference work, a walking encyclopedia; he knew all the books, authors, publication dates, bookshops, he knew all the latest improved editions, he was an indefatigable browser and bookworm. But he also had a sharp logical gift; he was a bit of a drudge. Yet the trait of his that the professors most welcomed was a truly delicious natural gift. He was able to nod for hours on end without getting tired. He was always in agreement. Never did he contradict a professor. And so it came about that Anton Wanzl was a significant presence in seminars and lectures. He was always agreeable, always quiet and conscientious, he tracked down the most obscure tomes, wrote out notes and announcements of lecture dates. And he also continued to hold coats: he was a Swiss guard to the professors, a doorman, an accompanist, and a page-turner.\ There was only one field in which Anton Wanzl had yet to make a showing, and that was love. He didn't need love. But then again, when he turned it over quietly in his mind, he was forced to agree that only the possession of a woman would assure him of the completest respect of friends and colleagues. Only then would the mockery come to an end, and he would stand there, Anton, impressive, respected, untouchable, the very quintessence of a man.\ Also, his immeasurable overbearingness cried out for a creature wholly devoted to him, that he could knead and shape as he pleased. Thus far, Anton Wanzl had obeyed. Now, he wanted to command. Only a loving woman would obey him in everything. But it needed to be gone about the right way. And going about something the right way, that was something that Anton knew a thing or two about.\ Little Mizzi Schinagl worked in the corsetry department of Popper, Eibenschütz & Co. She was a dark, pretty thing, with two large brown doelike eyes, a pert little nose, and a slightly short upper lip, exposing a set of shimmering little mouse teeth. She was also, however, "as good as engaged" to one Julius Reiner, traveling salesman specializing in ties and handkerchiefs, also in the employ of Popper, Eibenschütz & Co. Mizzi was fond of her clean-cut young man, but neither her little head nor her heart quite saw in Julius Reiner a husband for Mizzi Schinagl. No, she couldn't possibly give herself in marriage to a young man who just two years previously had been given a couple of resounding slaps by Herr Markus Popper. Mizzi wanted to have a husband to look up to, a gentleman, a social superior. A real woman, endowed with that innate sense and discretion that a man can only ever hope to learn, she found certain aspects of the specialist in ties and handkerchiefs not to her liking. Mizzi Schinagl would have preferred a young student, one of the swarm of young fellows in colored caps that waited outside for the female staff at the end of business hours. Mizzi would have loved to be spoken to by a gentleman like that on the street, only Julius Reiner always kept such an annoyingly close watch on her.\ But just then, her aunt, Frau Marianne Wontek, took in a nice new lodger in her apartment in the Josefstadt. Herr Anton Wanzl was very learned and serious-looking, but he was wonderfully polite and attentive, especially toward Fräulein Mizzi Schinagl. On Sundays, she would take him his afternoon coffee in his room, and the young gentleman always thanked her with a friendly word and a smile. Once he even asked her to sit with him a moment, but Mizzi mumbled something about not wanting to bother him, blushed, and slipped off to her aunt's room in some confusion. But when Herr Anton bumped into her on the street, then Mizzi was only too glad of his company, even taking a slightly roundabout route. She arranged to meet the student of philosophy, Herr Anton Wanzl, the following Sunday, and the next day quarreled with Julius Reiner.\ Anton Wand duly appeared, simply but elegantly clad; his colorless, pale hair was more carefully parted than ever, but some little excitement did seem to be perceptible on his cold white marmoreal face. He sat in the park next to Mizzi Schinagl, thinking hard about what he should say. He had never been in this awful situation before. But Mizzi knew how to chatter. She talked about this and that, the evening came alone, the perfumed lilac breathed, the blackbird sang, the month of May came giggling out of the undergrowth, and Mizzi Schinagl forgot herself and said out of the blue: "Oh, Anton, I love you." Herr Anton Wanzl was somewhat taken aback, Mizzi Schinagl more than somewhat herself: she needed to bury her burning little face somewhere, and could think of no better hiding place than in the lapels of Herr Anton Wand's jacket. This had never happened to Herr Anton Wanzl. His starched shirt front crackled audibly, but he mastered himself—after all, it was bound to happen sooner or later!\ (Continues...)\ \ \ Excerpted from The Collected Stories of Joseph Roth by Joseph Roth. Copyright © 1992 by Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch Köln and Verlag Allert de Lange Amsterdam. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. \ \ \ \

Introduction9The Honors Student17Barbara31Career40The place I want to tell you about ...47Sick People54Rare and ever rarer in this world of empirical facts ...66The Cartel71April: The story of a love affair79The Blind Mirror98The Grand House Opposite134Strawberries138This morning, a letter arrived ...166Youth173Stationmaster Fallmerayer180The Triumph of Beauty: A Novella202The Bust of the Emperor: A Novella227The Leviathan: A Novella248About the Stories277About the Author279About the Translator281

\ The Times [London]“Joseph Roth is one of the great writers of German of this century.”\ \ \ \ \ Nadine Gordimer“The totality of Joseph Roth's work is no less than a tragedie humaine achieved in the techniques of modern fiction.”\ \ \ Nadine GordimerThe totality of Joseph Roth's work is no less than a tragedie humaine achieved in the techniques of modern fiction.\ \ \ \ \ London TimesJoseph Roth is one of the great writers of German of this century.\ \ \ \ \ From The CriticsBorn in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and educated in Vienna, Joseph Roth wrote fifteen novels before his death in 1939. In the first of them, written in 1923, he presciently warns of Nazism, mentioning Hitler by name. Roth's seventeen shorter works of fiction, including several recently discovered pieces, appear in this brilliant translation. They may be among the most frustratingly inconsistent works of literature ever written. Roth, with a detachment reminiscent of Nabokov's, has a brilliant eye for the odd detail and uncanny states of being. But in many of these stories, Roth displays a broad, unimaginative streak of old-fashioned misogyny. "The Triumph of Beauty" begins with the description of a gynecologist who "treats the husbands, who suffer more at the hands of their wives than their wives do from their illnesses." "The Cartel," unconvincingly set in Boston (Roth never visited the United States), is an embarrassing stew of hardboiled reporters, gangland slayings and caricatured suffragettes. These failures of sympathy and Roth's heavy sarcasm—which alternate with exquisite delicacy of perception—create something akin to a pastoral Eden with land mines. \ —Penelope Mesic \ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ Belatedly recognized in this country, but long acclaimed in Europe for such brilliant, classic novels as The Radetzky March, Roth died in 1939 in the early days of WWII. The 17 stories in this collection display his diverse but sometimes erratic talent. In the early entries, Roth paints his plots and characters in short, broad strokes, a trait leading to abrupt, unpredictable plot twists that occasionally blur the effect of his shorter works. When he stretches out and delves into the irony and humor of European life, however, his narratives acquire considerable resonance. "Station Fallmerayer," written in 1933, is a heartrending account of an Austrian station master who becomes obsessed with a Russian countess he rescues from a train wreck, despite the effects his pursuit has on their respective marriages. "The Triumph of Beauty" works on a different level as Roth explores the impact of an attractive, fickle hypochondriac on her beleaguered husband. Several other narratives extend to novella length, and the collection also contains works that were intended as blueprints for novels, such as the vividly evocative, elegiac "Strawberries." His penultimate achievement, "The Leviathan," tells of a coral merchant preoccupied with the mystery of the sea, who falls for the lure of selling fake merchandise, only to join his precious original wares in the watery depths. This collection marks the first time Roth's short fiction (some of which came to light only recently) has been available in English, and although a few of these stories are immature early works, taken together they testify to the talents of a writer who was penetratingly prescient about the tragedies that marred the 20th century. (Feb.) Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThe Austrian-born Roth is probably best known for his 1932 novel, The Radetzky March, which portrayed how, through a quirk of fate, an unassuming soldier and his family are suddenly elevated to a higher station within the soon-to-be crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire, severing them forever from the life that they had known and loved. The detail with which Roth portrayed his country and customs in that novel is evident in this collection, which couples recently unearthed stories from Roth's early career with previously published stories and novellas from his career after fleeing the Nazis in 1933. His early pieces tend toward the ironic and personal, exposing fatal flaws in the sad lives of his heroes, like "The Honor Student" who puts ambition before love or the paper pusher who is foolishly loyal to his less-than-progressive employer in "Career." Roth's later works widen in scope and echo the times and feelings surrounding World War I, as in the thwarted would-be romance of "Stationmaster Fallmerayer" and the heartfelt requiem for the passing of monarchy in "The Bust of the Emperor." But the irony remains throughout, as does Roth's gift of storytelling, which is intentionally simple and direct. The volume is seemingly aimed at Roth's followers, but readers interested in the period will welcome it as well. Larger libraries will find this a good complement to Radetzky and Roth's other novels. Marc Kloszewski, Indiana Free Lib., PA Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAn important collection of 17 stories and (brief) novellas, all written between 1916 and 1940 by the Austrian writer whose superb novels (including The Silent Prophet and The Radetzky March) rank among the finest rediscovered fiction of recent decades. Roth (1894-1939), a Jew born in Galicia, spent much of his brief life in exile, from the rise of Nazism and from his own ironist's awareness of rigidly ordered old "worlds" collapsing (such as that of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy). Accordingly, his stories concentrate on ambitions unfulfilled and loyalties betrayed, as in the limpid "Barbara"(about a loving woman who means nothing to the men in her life, including the son for whom she sacrifices herself), and "April" (which might have been written by a clinically depressed Turgenev), about a young man on the make who quite casually moves on after his dalliance with a girl who's too fragile to live. Roth's genius for brisk characterizations and urgent empathetic voice effortlessly solicit our identification with such wounded and searching characters as the elderly nobleman (of "The Bust of the Emperor") who continues to perform dutiful acts of charity even after a ruthlessly efficient (Polish) "republic" renders his commitment to noblesse oblige obsolete, and the eponymous protagonist of the Flaubertian "Stationmaster Fallmerayer," whose romantic obsession with a Russian countess injured in a train wreck slowly, surely detaches him from all his responsibilities and relationships: it's a compact tragedy of passion concentrated into a harsh, unforgettable 20 pages. Best of all is Roth's last completed novella "The Leviathan," about a coral merchant engrossed in a sustaining fantasy suggestedby the curious exotic life forms that provide his livelihood, and eventually tempt him to ruin. It all turns on a masterly metaphor for the fragility of a life "that had not been linked to that of any other human being in this world." Essential, deeply satisfying fiction from one of the least known of the 20th-century's greatest writers.\ \