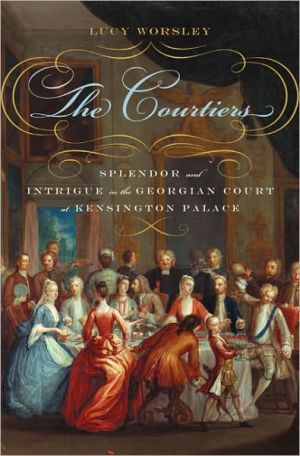

The Courtiers: Splendor and Intrigue in the Georgian Court at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is now most famous as the former home of Diana, Princess of Wales, but the palace's glory days came between 1714 and 1760, during the reigns of George I and II . In the eighteenth century, this palace was a world of skulduggery, intrigue, politicking, etiquette, wigs, and beauty spots, where fans whistled open like switchblades and unusual people were kept as curiosities. Lucy Worsley's The Courtiers charts the trajectory of the fantastically quarrelsome Hanovers and the...

Search in google:

Kensington Palace is now most famous as the former home of Diana, Princess of Wales, but the palace's glory days came between 1714 and 1760, during the reigns of George I and II . In the eighteenth century, this palace was a world of skulduggery, intrigue, politicking, etiquette, wigs, and beauty spots, where fans whistled open like switchblades and unusual people were kept as curiosities. Lucy Worsley's The Courtiers charts the trajectory of the fantastically quarrelsome Hanovers and the last great gasp of British court life. Structured around the paintings of courtiers and servants that line the walls of the King's Staircase of Kensington Palace—paintings you can see at the palace today—The Courtiers goes behind closed doors to meet a pushy young painter, a maid of honor with a secret marriage, a vice chamberlain with many vices, a bedchamber woman with a violent husband, two aging royal mistresses, and many more. The result is an indelible portrait of court life leading up to the famous reign of George III , and a feast for both Anglophiles and lovers of history and royalty. The Washington Post - Jonathan Yardley …an exercise in the higher (or, depending on one's view of royalty, lower) gossip. Worsley…writes breezy, chatty prose…The Courtiers is amusing and, among other things, a useful reminder that, contrary to what many believe, sex was not invented in the 1960s.

The Courtiers\ Splendor and Intrigue in the Georgian Court at Kensington Palace \ \ By Lucy Worsley \ Walker & Co.\ Copyright © 2010 Lucy Worsley\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-8027-1987-4 \ \ \ Chapter One\ To the Palace \ * * *\ 'Really, it must be confessed that a court is a fine thing. It is the cause of so much show and splendour that people are kept gay and spirited.' (James Boswell, 1763)\ On 25 April 1720, a special sense of anticipation was building in the fashionable parts of London. The party planned at St James's Palace that night was the most hotly anticipated court occasion for many years.\ Nowhere was the excitement greater than in the rambling old mansion called Leicester House. This building, dominating the north side of Leicester Fields, was the home of the king's son and daughter-in-law, the Prince and Princess of Wales, George Augustus (1683–1760) and Caroline (1683–1737). While the prince and princess were losing their looks and fast approaching middle age, they remained a jovial, lively and friendly couple.\ Tonight's entertainment, though, would sorely strain their good spirits. They were going to have to pay a reluctant visit to the court of King George I (1660–1727).\ The late afternoon saw Prince George Augustus berating a clumsy servant as he struggled into an outfit of peacock splendour. He aimed to be 'always richly dressed, being fond of fine clothes'.\ Bad-tempered, full of bluster, fond of music and of fighting, this prince would become best known as George II, the last British king to lead troops in person upon the battlefield. He struts through Britain's history books like a kind of tin-pot dictator: brusque, pompous and a little bit ludicrous. Despite his tantrums, though, he deserves at least a pinch of sympathy. Like all courtiers, he spent his days performing a part upon a stage.\ Unfortunately, for a man of his gaudy tastes, he was considerably shorter than average. He had bulging china-blue eyes and his prominent nose was rather Roman. He also had an imperious temper: 'vehement, and irritable', 'hot, passionate, haughty'. But his anger could cool as quickly as it came. He had the great redeeming feature of being passionately in love with his wife, the fat, funny and adorable Princess Caroline. He would rely upon her for the strength and steadiness to face the difficult evening that lay ahead.\ She, meanwhile, was growing flustered as the Women of her Bedchamber tried to lace up her stiff stays.\ Plump, yet pin-sharp, Princess Caroline had a sweet smile, and blossomed into beauty when her face and mouth were in motion. Wilhelmine Karoline of Ansbach, as she was born, had been celebrated in her youth as the 'most agreeable Princess in Germany'. Her arms were admired for their 'whiteness and elegance'; she had 'a penetrating eye' and an 'expressive countenance'. Princess Caroline could split sides with her amusing impressions, loved a quick-fire duel of wit and spoke English 'uncommonly well for one born outside England'. Friend of the philosophers Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton, she would in due course become the cleverest queen consort ever to sit upon the throne of England.\ With her greater intellectual skills, humour and sense of style, Princess Caroline would have made a far more successful heir to the crown than her husband, but the odds for opportunity were always stacked against eighteenth-century women. Caroline kept her husband subtly but firmly under her thumb, and always contrived 'that her opinion should appear as if it had been his own'.\ In spite of Princess Caroline's infectious laughter and her cleverness, and despite Prince George Augustus's visibly lavish love for his wife, he inflicted a regular humiliation upon her: he was carrying on an affair with one of Caroline's servants, and future conflict was inevitable.\ At the time of his birth in 1683, the possibility that George Augustus would become Prince of Wales had seemed almost preposterously small. Both he and Caroline came from dinky little principalities that now form part of modern Germany. They'd only immigrated to Britain in 1714, when George Augustus's father, later King George I, had unexpectedly inherited the British throne because of the accidental failure of the Stuart line of monarchs.\ Britain's previous queen, Anne, had endured seventeen pregnancies in a desperate but ultimately futile attempt to squeeze out an heir. Her failure to produce a healthy child brought the Stuart line to a stuttering stop, with the exception of her Catholic half-brother. Anne's elder sister, Mary, had deposed their father James II in 1688 because of his despotic and Catholic regime. This was the so-called 'Glorious Revolution'.\ The choice faced at Anne's death, then, was either to recall James II's Catholic offspring or to look back up the trunk of the Stuart family tree to identify a Protestant branch.\ The Act of Settlement of 1701 tidied up the problem. It specified that the small, Protestant house of Hanover should provide Anne's successors. This was to be at the expense of the exclusion of fifty nearer relatives, who were regrettably but unacceptably Catholic.\ Upon Anne's death in 1714, the Hanoverian succession unfolded surprisingly smoothly, and the small, provincial court of Hanover crossed the Channel to London. The Electoral Prince, Georg Ludwig of Hanover, became King George I of Great Britain, while his son and daughter-in-law became Prince and Princess of Wales.\ But the great transformation in their fortunes in 1714 was the beginning, not the end, of this family's troubles.\ All across London, the Prince and Princess of Wales's courtiers and supporters were likewise preening and squeezing themselves into their court clothes. As the sun sank, each of the ladies was reaching the end of a toilette that had taken two hours or more. 'Lud! Will you never have done fumbling?' grumbled many a modern lady to her maid.\ Once her figure had been transformed into the right shape by tight stays and a hooped petticoat, a female courtier was required to put on her court uniform. The 'mantua', as it was known, was an archaic, uncomfortable but supremely elegant form of dress. Pale forearms descended from wing-cuff sleeves with the requisite three rows of ruffles ('I am so incommoded with these nasty ruffles!'). Long trains spilt at the back from tightly seamed waists. The mantua's skirts were spread out sideways over immensely wide hoops, too broad to pass through a door. 'Have you got the whalebone petticoats among you yet?' Jonathan Swift wrote from court. 'A woman here may hide a moderate gallant under them.'\ Any female courtier would be altogether unrecognisable without her warpaint, 'pale, dead, old and yellow'. So maids were busily painting their mistresses with 'rosy cheeks, snowy foreheads and bosoms, jet eyebrows and scarlet lips', and puffing powder over piled coiffures. Once trussed up and coloured, the female courtiers resembled the beauties in Mrs Salmon's famous London gallery of waxworks, and had carefully to avoid the fire for fear 'of melting'.\ Meanwhile, the male courtiers were donning coat, waistcoat and breeches encrusted with embroidery. Their shoe buckles were jewelled, and each would rest a hand upon the hilt of a sword. On their heads, the itchy and sweaty full-bottomed periwig was still in fashion. Between each gentleman's left elbow and his side was clenched his chapeau-bras: a flat, unwearable parody of a hat, for the head was never covered in the presence of the king.\ 'Dress is a very foolish thing,' declared the arch-courtier Lord Chesterfield, and yet, at the same time, 'it is a very foolish thing for a man not to be well dressed'.\ Two junior members of Princess Caroline's household at Leicester Fields were preparing with particular care, because they and their colleagues would be the subject of intense and critical scrutiny on this special evening.\ Mrs Henrietta Howard was one of the six Women of Princess Caroline's Bedchamber. The Princess's most senior servants were the Ladies of the Bedchamber, peeresses one and all. The Women of the Bedchamber, slightly lower down the social scale but still well-born, did the real work of dressing and undressing, watching and waiting. But Henrietta had both an official and an unofficial job. As well as being Princess Caroline's servant, she was also the recognised mistress of Caroline's husband. Neither role brought her much pleasure.\ Now in her thirty-first year, Henrietta was not an astounding beauty. Yet her build was slim, she had 'the finest light brown hair' and she was 'always well dressed with taste and simplicity'. (This 'beautiful head of hair' had played a small but significant role in her life story so far.) Unlike many royal mistresses, she had not exploited her position to amass influence and riches. She was of a 'romantick turn of mind', thoughtful, gentle, but 'close as a cork'd bottle'. Her friend, the poet Alexander Pope, accused her of 'not loving herself so well as she does her friends', and he also described a grievous 'air of sadness about her'.\ No wonder, for her life had been difficult. She was now living apart from her brutal, heavy-drinking husband. Orphaned at a young age and looking for security, marriage had looked like a safe option. But marrying Charles Howard had turned out to be a terrible mistake.\ And she had very little hold on the affections of the other problematic partner in her life, her royal lover. Prince George Augustus rather reluctantly felt that it would be beneath his princely dignity to remain faithful to his wife, and he had a mistress only out of a sense that he ought to. So he was often cruel and abrupt with Henrietta.\ She, too, was dreading the palace drawing room. Despite her privileged position as royal mistress, for her it held the risk of an unpleasant encounter with the husband who'd given her nothing but unhappiness, bruises and destitution.\ By sharp contrast, Henrietta's junior colleague in the royal household, Molly Lepell, was dancing round her dressing room in delight. She was one of the merry Maids of Honour, a good-looking and audacious gang of girls whose job was to decorate and animate Prince George Augustus and Princess Caroline's court.\ Born in the very first year of the eighteenth century, the now nineteen-year-old Molly was nicknamed 'The Schatz , German for 'treasure'. Part of her charm was her bottomless fund of jokes. She even mockingly (and wrongly) disparaged her own looks. 'I am little,' she said, but at least 'there are many less'. 'I am strait, the shoulders low ... the neck long, the throat frightful, the head too large, the face flat ... as to my hair it has nothing to make it tolerable, it grows badly, not thick, and of a pale and ugly brown'.\ In fact, she had big grey eyes, lustrous skin and an elegant, waiflike figure; she was the darling of the celebrity-obsessed London crowds.\ Molly's father had bequeathed her the curse of breeding without the money to flaunt it. He'd fraudulently entered his baby girl upon the payroll of his army regiment, so that she got a salary unearned. But the scam could not last, and Molly was sent out to earn her living as a palace good-time girl at a very young age. She certainly had all the easy graces of the courtier, having been 'bred all her life at courts'. She also understood Latin perfectly well, though wisely she concealed her skill. (A lady's 'being learned' was 'commonly looked upon as a great fault'.)\ Uniquely among her frivolous friends, her fellow Maids of Honour, Molly was a good keeper of secrets. She was astonishingly composed and inscrutable for someone so young. Some people inevitably found her polished professional social manner insincere: she seemed to be 'of the same mind with every person she talked to'. Others found her playful wit cutting rather than amusing, and her jokes 'extreme forward and pert'.\ But this smooth surface disguised a young woman who was 'very passionate' underneath. 'I find it beneath me not to be able to disguise it,' Molly explained, and she hid the essence of herself behind her endless jokes. 'I look upon felicity in this world not to be a natural state, and consequently what cannot subsist,' she wrote in a rare unguarded moment. Depression was her great secret enemy.\ Tonight, for once, pleasure and excitement held it at bay. Unlike the other occupants of Leicester House, Molly could not wait for the evening to begin. The other Maids of Honour had no inkling that she'd recently thrown herself headlong into a mad, bad affair of the heart. The night would bring her once more into the company of her beloved.\ At about 7 o'clock, sedan chairs carrying those lucky enough to be going to court began their swaying journeys across London. It would be foolish to walk: the jeers of hostile passers-by, rain and mud were all to be avoided, and the streets of the St James's district ought certainly 'to be better paved'.\ TO THE PALACE\ A bristling bevy of red-clad Yeomen of the Guard preceded the sedan chairs of the Prince and Princess of Wales as they led the procession of their servants and supporters out of Leicester Fields. Ladies in court dress had to be literally crushed into sedan chairs, 'their immense hoops' folded 'like wings, pointing forward on each side'. To accommodate their 'preposterous high' headdresses, they had to tilt their necks backwards and keep motionless throughout the journey.\ Their destination, the old palace of St James's, was not particularly impressive. It had been a poorly designed, makeshift mansion for the monarchy since the great palace of Whitehall burned down in 1698. An eighteenth-century guidebook called it 'the contempt of foreign nations, and the disgrace of our own'; a visiting German confirmed that it was 'crazy, smoky, and dirty'.\ Although cramped and unsuitable, St James's Palace still provided the stage upon which the Georgian court's most important rituals were performed. To the courtiers its atmosphere was heady, dangerous but absolutely irresistible: 'full of politicks, anger, friendship, love, fucking and foppery'.\ Many of the people who weren't invited to palace parties would have claimed the court was no longer the beating heart of the nation that it had once indisputably been. There was Parliament, now, as an alternative arena for politics. Kings and queens no longer ruled by divine right. Monarchy was on the decline.\ And yet, while all this was true, the early years of the eighteenth century were to see a last great gasp of court life and a late flowering of that strange, complex, alluring but destructive organism called the royal household.\ The personal was still political at the early Georgian court. The king's mood, even his bowel movements, could determine the fate of many, as even now he was called upon to make real decisions about the running of the country. His opinion still mattered, and, as contemporaries showed by packing themselves into its drawing room or by begging for jobs as servants, the palace was still a seat of power.\ * * *\ As they approached the palace's lofty red-brick gatehouse, the sedan chairmen carrying Henrietta and Molly in Princess Caroline's wake had to force a passage through a raucous, torch-lit crowd. Hundreds of people had gathered expectantly to catch a glimpse of the blazing 'beauties' arriving in their jewels.\ Molly Lepell, along with her friend Mary Bellenden, another Maid of Honour, received the loudest sigh of admiration. Although they were not yet twenty, these two were the toast of their generation, and each was as lively and as pretty as the other. Then, as now, society beauties provided the shot of style and celebrity that the masses craved. One popular London ballad promised to expose\ What pranks are played behind the scenes, And who at Court the belle – Some swear it is the Bellenden, And others say Lepell.\ The arrival of the matchless Mary and Molly elicited the kind of greedy, semi-salacious gasp that still runs up and down red carpets today when the stars appear.\ Through the palace gatehouse lay the Great Court, where soldiers kept guard. It was also called the 'Whalebone Court' after the whale's skeleton, 20 feet long, that was clamped to one wall. Here a sea of servants and stationary sedan chairs jostled to drop people off before the fine columned portico sheltering the entrance to the royal apartments. The palace authorities complained constantly about all this traffic blocking the courtyards and passages.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Courtiers by Lucy Worsley Copyright © 2010 by Lucy Worsley. Excerpted by permission of Walker & Co.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Contents\ List of Illustrations....................ix\ Map....................xiii\ Family Trees....................xiv\ Cast List....................xviii\ Preface....................1\ ONE To the Palace....................7\ TWO The Petulant Prince....................23\ THREE The Pushy Painter....................55\ FOUR The Wild Boy....................85\ FIVE The Neglected Equerry....................111\ SIX The Woman of the Bedchamber....................135\ SEVEN The Favourite and His Foe....................185\ EIGHT The Queen's Secret....................221\ NINE The Rival Mistresses....................257\ TEN The Circle Breaks....................291\ ELEVEN The Survivors....................325\ Acknowledgements....................335\ Sources....................341\ Notes....................355\ Index....................395

\ Publishers WeeklyThe nasty spats of Charles and Diana pale in comparison to the bloody family battles waged by the prince's dysfunctional ancestors, Georges I and II. Fathers turned against sons and vice versa, and family quarrels led to expulsions from the royal palaces. A respected if not popular sovereign but a diabolical husband and father, George I denied his adulterous wife access to her young son, the future George II, and imprisoned her for 33 years in a remote German castle. George II himself endured a forced separation from his son, Frederick, yet when years later the grown Frederick arrived in London, George banned him from the palaces as he had been banned by his father. Worsley (Cavalier), chief curator at the Historic Royal Palaces, recreates the first two Georgian courts, depicting rival royal mistresses; a disaffected equerry; a "wild," probably autistic boy found in the woods and kept as a pet by George II's wife; and scheming courtiers, as well as Kensington Palace's various architectural renovations. Although some of the court minutiae are too trivial or esoteric for modern consumption, Worsley overall serves up a tasty slice of 18th-century life that is colorful, gossipy, and authoritative. Color illus. (Aug.)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn 1725, England's George I commissioned court painter William King to decorate the grand staircase of Kensington Palace. The resulting trompe l'oeil mural included 45 portraits of royal servants from clerks to maids of honor. Worsley (chief curator, Historic Royal Palaces; Cavalier: A Tale of Chivalry, Passion, and Great Houses) focuses on some of the portrayed figures as she tells the story of court life from 1714 to 1760, in the time of the battling father and son, George I and George II, German-speaking rulers brought to England with the demise of the Stuarts. Among those whose lives are followed: George II's mistress Henrietta Howard, who served as woman of the bedchamber to his tolerant wife, Queen Caroline; the beautiful maid of honor Molly Lepell, who ran off with resident court cynic John Hervey; a "wild boy" kept as a pet by the king; and George I's Turkish valets Mustapha and Mohammed. VERDICT In contrast to Worsley's brilliantly organized, meticulously researched Cavalier, this book does not flow well; it is rambling and unfocused, a gossipy account of Hanoverian court life suitable for reading perhaps by some royal watchers but not likely to satisfy those most interested in the era.—Stewart Desmond, New York\ \ \ Jonathan Yardley…an exercise in the higher (or, depending on one's view of royalty, lower) gossip. Worsley…writes breezy, chatty prose…The Courtiers is amusing and, among other things, a useful reminder that, contrary to what many believe, sex was not invented in the 1960s.\ —The Washington Post\ \