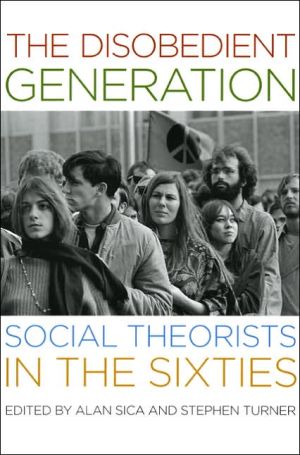

The Disobedient Generation: Social Theorists in the Sixties

The late 1960s are remembered today as the last time wholesale social upheaval shook Europe and the United States. College students during that tumultuous period - epitomized by the events of May 1968 - were as permanently marked in their worldviews as their parents had been by the Depression and World War II. Sociology was at the center of these events, and it changed decisively because of them.\ The Disobedient Generation collects newly written autobiographies by an international...

Search in google:

The late 1960s are remembered today as the last time wholesale social upheaval shook Europe and the United States. College students during that tumultuous period—epitomized by the events of May 1968—were as permanently marked in their worldviews as their parents had been by the Depression and World War II. Sociology was at the center of these events, and it changed decisively because of them. The Disobedient Generation collects newly written autobiographies by an international cross-section of well-known sociologists, all of them "children of the '60s." It illuminates the human experience of living through that decade as apprentice scholars and activists, encountering the issues of class, race, the Establishment, the decline of traditional religion, feminism, war, and the sexual revolution. In each case the interlinked crises of young adulthood, rapid change, and nascent professional careers shaped this generation's private and public selves. This is an intensely personal collective portrait of a generation in a time of struggle.

The Disobedient Generation \ SOCIAL THEORISTS IN THE SIXTIES\ \ The University of Chicago Press \ Copyright © 2005 The University of Chicago\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-226-75625-7\ \ \ \ Chapter One \ ALAN SICA\ Introduction\ What Has 1968 Come to Mean?\ During the sixties, Alan Sica worked full-time in a paper mill, as a luggage handler at a Greyhound Bus station, in a Philip Morris factory on the Marlboro assembly line, in a bank reconcilement unit, and in several libraries. He also played guitar and harmonica, rode motorcycles, and tried not to be arrested for incorrect political attitudes. After that, he taught at Amherst College, University of Chicago, University of Kansas, University of California, Riverside, Pennsylvania State University, and University of Pennsylvania. He was associate editor of the American Journal of Sociology and Contemporary Sociology, editor and then publisher of History of Sociology, and editor-in-chief of the American Sociological Association (ASA) journal, Sociological Theory. He was chair of the Theory Section of the ASA in 1997. Between 1989 and 1998 he served as associate editor (for social sciences) and contributor to the American National Biography. In 1997-98, he was deputy editor of the American Sociological Review. Since 1991 he has been professor of sociology at Penn State, where he is founder and director of the interdisciplinary SocialThought Program. His books include Hermeneutics: Questions and Prospects; Weber, Irrationality and Social Order; Ideologies and the Corruption of Thought: Essays of Joseph Gabel; What Is Social Theory? The Philosophical Debates; The Unknown Max Weber: Selected Essays of Paul Honigsheim; Max Weber and the New Century; Max Weber: A Comprehensive Bibliography; and Social Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Present. He has also worked as a professional violinist. He has been married for thirty-four years and helped raise three sons.\ This book comprises autobiographical chapters written by noted scholars and activists, most of whom were born between 1947 and 1950, with a few outliers as far back as 1944 and up to 1952. They therefore came of age during the cultural revolution of the late 1960s and early 1970s that swept over Europe and the United States and even penetrated Mao's China (though in a different form, of course). This unforgettably raucous period has ever since been recognized as a distinct cultural/political epoch that in reductionistic shorthand is called "the Sixties," unique as much for its popular music and films as for its more durable political and social changes. This disparate group of authors (who agreed in this rare instance, uncharacteristically and not without genuine initial hesitation, to evaluate themselves rather than society at large) are unified principally by their substantial scholarly reputations and not by any standard "party line" that might reflect their experiences as students or apprentice intellectuals. They now work in Britain (3), Canada (1), France (2), Germany (2), Italy (1), and the United States (10), but despite the obvious differences the specific conditions of work lend to their stories, there are common threads that clearly bind them to a special generational experience, the influence of which has not left their imaginations these thirty-five years later. Each was invited to consider the impact this vast sea change-symbolically capsulized as "the events of '68"-had on their development as individuals, scholars, and politically astute participants during the more pacific decades that followed. What did it mean to be formed, intellectually, politically, and personally, between about 1966 and 1972? Is there a definably "Sixties" way of seeing the social world and of reacting to it as a scholar and social theorist?\ Our autobiographers have answered this invitation with brilliant diversity of tone and substance, and all speak eloquently for themselves, thus relieving me of the standard duty, as the volume's introducer, of recapitulating their analyses and stories. What these memoirs do presuppose, however, is some general knowledge of what the French have ever since called "the events of May"-the global political conflagration that actually began in late April 1968 and continued for most of that year. What historians have termed "the hard year" (O'Neill 1971), "the pivotal year" (Morgan 1991, 154), or even "America's annus horribilis" (Marwick 1998, 642-75) is perhaps best revived in memory by these words of the time: "The May Revolution of 1968 was a disturbance in French society on a scale to break the seismograph. It was the sort of event that sets your mind reeling for months afterwards as you try to make sense of it" (Seale and McConville 1968a, 9). The "ruckus" or "troubles" (as the Right tagged this period) began among a small group of students in New York City at Columbia University and quickly spread to Paris, Oxford, London, Rome, Madrid, Berlin, Prague, Belgrade, and Peking (now Beijing), not to mention Berkeley, Madison, Ann Arbor, and dozens of other American college campuses. Many thousands of students took part, sometimes aided by the working classes (especially in France and Italy), and no one who read a newspaper or watched television news doubted that indeed (forgive the cliché), "the times they were a 'changin.'"\ Epochal 1968 has become more or less unimaginable when set beside any single subsequent year in Western history. It is not easy to conjure up that time, both for those who were not there and for those participants whose memories can no longer contain the fearsome thrill of societal chaos that seemed to engulf the most "civilized" parts of the modern world. The uniquely re-creative societal setting that gave rise to the chapters that fill this book can most efficiently be recalled by listening to the semiofficial voice of the era, Time magazine's feature writers. The "shocking" cover for June 7, 1968, displayed a headshot of an unsmiling college graduate (University of California, Los Angeles, student-newspaper editor, Brian Weiss) wearing a peace symbol on a chain, in full beard and mortarboard, over the caption, "The Graduate 1968" (an obvious reuse of the 1967 Dustin Hoffman film that made him a star and helped define a generation: "Plastics, son, plastics"). A diagonal banner across Time's cover coyly read "Can You Trust Anyone under 30?" an ironic play on a famous contemporary expression about "elders" over thirty and their inherent duplicity. The six-page article that followed, entitled "The Cynical Idealists of '68" (1968, 78), began this way:\ The troubled and troublesome college Class of 1968 tends to have a sober, even tragic view of life. They were high school seniors in [the] year that John Kennedy ... was shot.... They were college seniors in the year that Martin Luther King, the Negro leader who tapped their idealism and drew them into social protest, was murdered in Memphis. Throughout all of their college careers, the war in Viet Nam has tormented their conscience, forced them to come to personal decisions relating self and society, country and humanity, life and death. With the lifting of most of the graduate school deferments, the men of '68 face the war and those existential issues as an immediate, wrenching reality. Such pressures, direct and indirect, have had a profound impact on the 630,000 seniors who will pick up diplomas this spring.... Those who are in the really new mold sometimes show it by a defiance in dress: beards beneath the mortarboards, microskirts or faded Levis under the academic gowns. More often, and far more significantly, it emerges in a growing skepticism and concern about the accepted values and traditions of American society. Some of these graduates will become draft dodgers. Many smoke pot. Fewer than ever remain virginal. Yet it is also true that the cutting edge of this class includes the most conscience-stricken, moralistic, and, perhaps, the most promising graduates in U.S. academic history.\ The authors then point out that students (and, surprisingly, allied factory workers) brought the French economy to a standstill and humiliated the previously untouchable de Gaulle, forced Czechoslovakia into an anti-Soviet openness, pressured the authoritarian government of Spain, demonstrated angrily in Germany, and did the same thing in Italy. In the United States, the most unlikely candidate, Eugene McCarthy, a peacemonger, became the first "young people's" representative in the race for the presidency. Observers all over the world, most of them "over thirty" and therefore by definition "the enemy of youth," agreed that the world had been turned upside down almost entirely without warning and that the bases of social order and control were under attack globally. It must have seemed to those familiar with German folklore that the Pied Piper of Hamelin (perhaps in the person of Bob Dylan or Mick Jagger) had gaily crossed the world that spring of 1968, and young people heard the tune and began a frenzied dance, even while the seductive sounds escaped their parents' ears entirely: "Something is happening here, but you don't know what it is-do you, Mr. Jones?" (Dylan 1965).\ As a way of reentering that enchanted, but dangerous period, consider some voices of the time at their most unvarnished:\ "We are tired of seeing the same old fogies running everything, making promises and not fulfilling them. We have realized that students and young people in this country must take things into their own hands." These sentiments, tumbling angrily out of the mouth of an intense student, were, as it happens, uttered in Serbian. But they could equally well have been delivered in French, Italian, or English [or German, Polish, or Spanish]. For in widely separated corners of Europe last week, thousands of youngsters were battling for what their intellectual mentor, German-born sociologist Herbert Marcuse, has taught them to think of as "the liberation of individuals from politics over which they have no effective control." ("Into Their Own Hands," 1968)\ An intelligent but dyspeptic account of Marcuse soon appeared in the haute bourgeois hardbound "magazine," Horizon, along with a long companion piece denouncing the new face of "anarchism" (Burrow 1969; Stillman 1969). In simpler syntax and without the Marcusean pedigree, note this heartfelt observation published on May 3, 1968, from Mrs. M. H. Medearis of Brentwood, Missouri, in a letter to Life magazine (the most popular outlet of middle-brow sentiment at the time), where she confessed that, "since the death of Martin Luther King, I've wished that I were a Negro. I want to fully understand and hurt even more than I do. My sympathetic, complacent, Midwestern attitude hasn't done me or anyone else any good." One week later, in the May 14 issue of Life's main competitor, Look, the letters page revealed an entirely different mindset, though one could easily imagine Mrs. Medearis sharing the sentiments of her countrymen when they wrote as follows about the Ohio "draft dodgers" who had been featured in the April 2 issue of that magazine: "I must say, I was appalled by your article. I mean, after reading it several times, I got the idea that you were in favor of that kid. He deserved to be put in 1-A [for immediate draft into the army for Viet Nam duty]. After all, he didn't belong to a church, and he believed in a lot of crazy foreign writers like Socrates. The trouble with kids nowadays is that they get all involved with opposition to war, and they worry so much about morality and kindness to others that they forget the basic teachings of Christianity that have made America great.... Frederick George Farley, Prospect Park, Pennsylvania." One must assume (in a pre-Monty Python, pre-Saturday Night Live public sphere) that this was written sincerely, especially considering the rest of the letter, which becomes ever more earnest and self-righteous. None other than Senator Edward M. Kennedy added that "the [entire] issue was interesting and informative, and I was particularly pleased at the intelligent discussion of problems in the current selective service system." Brent Parsons of Central Michigan University seconded Kennedy's opinion: "Congratulations to Anthony Wolff on his candid article on local draft boards ["Draft Board No. 13, Springfield, Ohio"]. Certainly exposure of this archaic and reprehensible system is long overdue. The author's comments reflect the thoughts of many young people today who find themselves in a desperate quandary. Because of an 'implied' threat by many draft boards, the freedom of speech and assembly has been blatantly denied. To travel 10,000 miles to fight despotism is hardly necessary when we can find it at any one of 4,084 local draft boards." Yet once again from the other side, Dianne Cohen of Westfield, Massachusetts, had this to say: "I was thoroughly disgusted by the attitude taken in your article. Why is the draft dodger made a celebrity? Their little speeches are quoted, pictures are taken of them and their wives with various anti-American captions such as 'No political idea is worth another man's life.' If we used that as our doctrine, we'd still be paying tea taxes to England!" Were I asked to produce a short document that summarized the zeitgeist prevalent in spring 1968, these four letters from page 16 of Look would serve well enough.\ Returning to the letters section of Life's May 3 issue, a range of topics are brought up, including the presidential run of "Clean Gene" McCarthy, "who has sensed the unprecedented potential of American youth, who has dared to challenge the strategy of political and union 'bossism,'" wrote John D. McCarthy of Brooklyn. Robert Kennedy's candidacy, Lyndon Johnson's decision not to run again, military supply lines in Viet Nam, and "the piousness of joggers" all occasioned letters, but by far the most numerous (eight letters), irate, and argumentative pertain to the rock group, The Doors: the "article 'Wicked Go the Doors' (April 12) is the first intelligent and serious coverage of the progressive sounds that I have seen in a non-underground publication" (Richard B. Davidon, Broomall, PA). T. P. Lynch from Troy, NY, wrote "It seems obvious the author is suffering from the first stages of the ever-spreading middle-age syndrome. This phase is marked by the sufferer's pawky ability to perceive great beauty in something he does not understand" (which may be the last time any writer to a newsmagazine used the word "pawky," meaning shrewd, witty, crafty, orsly). Mrs. A.M. Ingalls (Pasadena) could not contain herself:\ One is revolted not just by the behavior of The Doors' "leader," Jim Morrison. After all, when one imagines diapers in place of leather jeans and a pacifier in place of the microphone, everything else-the baby curls, sullen pout, spitting, yelling, and the use of the universal 2-year-old vocabulary, 'I want' and 'now'-seems quite in keeping. What repels one more is the misplaced sentiments of those who not only give attention to such behavior but marvel at it, pay for it, take their children to witness it, write about it, stand for it! Infantilism is the major affliction of our society today.\ -and not, presumably, warmongering, racism, poverty, sexism, environmental ruin, and the other dozen "causes" with which the Sixties have since been permanently linked.\ Extremely typical of the time, at least as I recall it at eighteen, was this commentary from Salt Lake City, Utah, by Theron D. Gregg: "Certain authors seem to glorify the acid-tripping, pot-smoking, speed-shooting type of movement that rock groups, like The Doors, seem to be associated with. On the other hand, police, people over 25 and authority in general get a bum-rapping. If someone had given the jerks like Morrison a good shot in the can when they were 9 years old, they might have become social-climate changers like John Kennedy or Abe Lincoln, instead of the youth-exploiting fops that they are." Sociologists of the media, of knowledge, of politics, and of culture will point out that a "self-selection bias" is at work in the words of letter writers, since such a tiny percentage of people with strong sentiments ever bother(ed) to send their remarks to a magazine or newspaper for public dispersal (particularly in the days before e-mail). Nevertheless, as I remember, and judging from the commentaries by my colleagues in this book, the accumulated bile that sprang from older people as they evaluated "The Youth Movement," "The Generation Gap," "The Counterculture," "The Antiwar Movement," "The Psychedelic Scene," "Haight-Ashbury/ Hashbury," "The Woodstock Generation"-however one chooses to label this congeries of semirelated events and persons-could have filled a small lake in Orange County. Mr. Gregg's letter could have been read in virtually any newspaper or magazine of the time-and probably was.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Disobedient Generation Copyright © 2005 by The University of Chicago. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

PrefaceIntroduction : what has 1968 come to mean?1Losing faith21The sixties and me : from cultural revolution to cultural theory37Antinomian Marxist48My back pages72That's not why I went to school94The sociology of power and justice : coming of age in the sixties114Life in the cold129Becoming a sociologist in Italy141A pragmatist from Germany156Culture of life176Dionysus and the ideals of 1968196From Switzerland to Sussex205Always a foreigner, always at home221The two bodies of May 1968 : in common, in person252The 1968 student revolts : the expressive revolution and generational politics272High on insubordination285Ontological disobedience - definitely! : (maybe)309Falling into Marxism; choosing to stay325

\ Human StudiesAn interesting addition . .. to the small body biographical and autobiographical material on sociologists. . . . By showing how the content of sociology writing relates to career experiences and trajectories . . . social theory is made to come alive and the tacit knowledge circulating amongst producers is made explicit.—Charles Crothers, Human Studies\ — Charles Crothers\ \ \ \ \ \ Douglas Kellner“The Disobedient Generation is a tremendously engaging volume that collects intellectual and in some cases political autobiographies of a generation of some of the best contemporary social theorists who came of age roughly in 1968 and went on to be distinguished in the field of sociology. The text is in itself an interesting sociological work, exploring how those individuals who lived through the experiences of the ‘60s came to seek a career in sociology and how their formative ‘60s experiences influenced them during their academic lives. Many people within the field and even those outside of it will find this collection fascinating.”--Douglas Kellner, University of California, Los Angeles\ \ \ \ \ Robert J. Antonio“The Disobedient Generation provides a very compelling portrait of the lives of a diverse stratum of leading sociologists who were coming of age in the late sixties. These original essays explore how the experiences of that unique era helped shaped these academics’ lives, careers, and theoretical work—work that still bears the ‘60s imprint in one way or another. As such, it also offers a fascinating chronicle of a period of change in sociology and in the wider society as well.”--Robert J. Antonio, University of Kansas\ \ \ \ \ \ \ Human Studies"An interesting addition . .. to the small body biographical and autobiographical material on sociologists. . . . By showing how the content of sociology writing relates to career experiences and trajectories . . . social theory is made to come alive and the tacit knowledge circulating amongst producers is made explicit."—Charles Crothers, Human Studies\ \