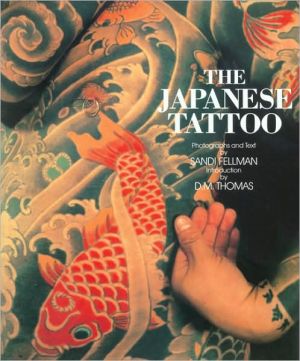

The Japanese Tattoo

A crimson fish wrestles a man. A horned demon stares menacingly. These vivid scenes are tattoos, created in pain, incised in the flesh of the Yakuza, Japan's feared secret society of gangsters. They are the visions of the Irezumi, the legendary tattoo artists, who spend years creating living masterpieces. Photographer Sandi Fellman describes this strange and violent world both in her text and in her stunning, large Polaroid photographs.\ Other Details: 66 large color plates 120 pages 10 x 10"...

Search in google:

A crimson fish wrestles a man. A horned demon stares menacingly. These vivid scenes are tattoos, created in pain, incised in the flesh of the Yakuza, Japan's feared secret society of gangsters. They are the visions of the Irezumi, the legendary tattoo artists, who spend years creating living masterpieces. Photographer Sandi Fellman describes this strange and violent world both in her text and in her stunning, large Polaroid photographs. Other Details: 66 large color plates 120 pages 10 x 10" Published 1987psychotherapy based on the analysis of tattoos. It would not be necessary to associate from dreams; the dreams would be visible. Of course, the personality of the tattooist would be a complicating factor—and therefore an enrichment. Jung, with his emphasis on the archetypal, would have found the irezumi marvelous subjects; Freud would have traced the sadism of the tattooist, the masochism of the tattooed, to the Oedipus complex. The art of irezumi, we learn, may have begun with the branding of malefactors. "These men," Freud might have said, "still wish to be punished for their incestuous and parricidal desires. They would prefer to be flayed—but that will come after their death." Maleness, machismo, coupled with the grotesque . . . that seeming contradiction is built into the myth: the same used to be said of white girls in relation to black men. We return to the mixture of seduction and repulsion, in face of perverse. Most of us, from time to time, use sex as a needle to break through the unfeeling skin of routine existence. Looking at the woman's back in this book, I know that making love to her would be making love to the tattoo more than to the woman. The wives of the male irezumi, Ms. Fellman suggests, experience that erotic displacement. It is not unlike the fetishist's need to interpose a symbol—fur or leather, garter belt or high-heeled shoes—between himself and his naked lover. Both fetishism and irezumi are largely the preserve of men; but also of magical and creative power: for love can be strengthened by the conjunction of a symbol. Still, it would not surprise me if, for most irezumi, the deepest relationship is with the master, so tirelessly penetrating them. I, a writer, an improvisor with words, envy and admire these artists who can bring their work, each day, to a point of completion. Not for them the wastepaper basket, piled high with rejected drafts; they cannot rip off the patch of skin and say, "We'll begin again." Each session must produce the equivalent of a perfect haiku, in which the ephemeral and the universal touch. Do the tattoo masters ever experience the despair of Western artists when things will not go right? Or that rending of the spirit described by Yeats: "The intellect of man is forced to choose/Perfection of the life or of the work"? I suspect they do not. I wish I knew their secret. Sandi Fellman's book does not and could not provide the answer; but it has made me more aware of the question—and of other, equally fascinating, questions—and I am grateful. Library Journal American photographer Sandi Fellman used a rare large size Polaroid camera to create these photos of Irezumi Japanese men and women who wear elaborate full-body tattoos. Fellman treats the tattoos as artworks and their creators as artists. Her text touches on the tattooing process, common motifs, the sociology of the tattoo, and relationships between the tattoo masters and their clients. Author D.M. Thomas has contributed two pages of his reactions to these unusual and even disturbing images. The 46 color plates in this volume, most of them whole body nudes, should prove provocative, fascinating, or repellant to a wide variety of library patrons. Kathryn W. Finkelstein, M.L.S., Cincinnati

Introduction by D. M. Thomas\ Irezumi is a defense, a shield. The tattoo says, If you approach too closely, beware! It is like the Medusa, with snakes in her hair, of Western mythology, and like Keats's snake-woman, the Lamia . . .\ "Eyed like a peacock, freckled like a pard,\ Vermilion-spotted, and all crimson-barr'd . . ."\ The irezumi's skin, which has borne the fiery pain of the needles, becomes cool, reptilian. The images of dragons, jagged lightning flashes, fish scales, and the ripplings of the moving body that a photograph cannot capture, increase the effect of a defensive barrier. Do the irezumi defend themselves against their emotions? Against the technology, consumerism, and conformism of modern Japan? The commuter in his business suit, who is secretly wearing feminine underclothes, may be an irezumi. Secrecy. Separateness. The mirror. Recognition of an artist's work can assume macabre, practical overtones in the case of the Japanese tattoo masters: it can help to identify a murder victim.\ Every irezumi—a living painting! Imagine it in the United States. A mangled corpse is dredged up from the Hudson River. "Send for the master." He is taken into the morgue, inspects the poor victim, and says, "Undoubtedly a Chagall." Cops and medics crowd around eagerly as the expert points out the unique qualities of the master. The word spreads: "We brought up a Chagall this morning." Then the Metropolitan Museum becomes interested, bids for it, adds it to the Picasso-prostitute knifed in her room the previous month. . . .\ Idea for a Japanese short story. A master looks at the corpse of a young man, once his homosexual lover, and says, "This is a Horiyoshi." Heis divided between admiration and jealousy. He does not look at the young man's face.\ East meets West in this book. Sandi Fellman's clear and intelligent art makes use of the most advanced photographic technology. Her subjects are people who have chosen to suffer years of torture, and perhaps even shortened their lives, in order to make their bodies look unnatural. East meets West, yet the two do not hold together. They seem to struggle against each other, and shy away. What was happening in the mind of the artist, as she took the photographs, and in the minds of the irezumi who allowed her to do so? Such questions do not occur to me in the case of the more conventional photography; they occur to me here because of the sheer alienness of the subjects. I can no more get inside their painted skin than I can get inside the carp that adorns many of them.\ I find—I should add—the Japanese car worker, who writes a suicide note to his boss instead of his wife, equally unknowable.\ Zen Buddhism teaches that enlightenment comes from within, not from an external agency. The tattoo becomes a manifestation of the man or woman's inner life. What pictures would modern Europeans or Americans choose as manifestations of their inner reality? Most of us, I suspect, would find it difficult to choose a symbolism capable of expressing our deepest values. The more sensitive would fall back on subjective imagery, such as the depiction of a loved person, but the streets would also be filled with the faces and bodies of fashionable idols—football players and TV personalities. Symbolism, in our culture, is dead.\ And how would we suggest, without the aid of dragons, lightning flashes, devils, and skulls, the dark side of our souls? We would probably not dare to; instead, we would safely externalize it. Antinuclear protesters would be marked with mushroom clouds, antivivisectionists with tortured rabbits.\ Under the painted skull of Horikin is a mind more alive with signals than all the microcomputers of Sony; and under all of those signals lies the unconscious. Compared with that cosmic design, that tattoo imprinted by living, all his years of art are less than one touch of his needle. Yet—to an extent, at least—he wears his life on his skin, and it would be easy to imagine a psychotherapy based on the analysis of tattoos. It would not be necessary to associate from dreams; the dreams would be visible. Of course, the personality of the tattooist would be a complicating factor—and therefore an enrichment. Jung, with his emphasis on the archetypal, would have found the irezumi marvelous subjects; Freud would have traced the sadism of the tattooist, the masochism of the tattooed, to the Oedipus complex. The art of irezumi, we learn, may have begun with the branding of malefactors. "These men," Freud might have said, "still wish to be punished for their incestuous and parricidal desires. They would prefer to be flayed—but that will come after their death." Maleness, machismo, coupled with the grotesque . . . that seeming contradiction is built into the myth: the same used to be said of white girls in relation to black men. We return to the mixture of seduction and repulsion, in face of perverse. Most of us, from time to time, use sex as a needle to break through the unfeeling skin of routine existence.\ Looking at the woman's back in this book, I know that making love to her would be making love to the tattoo more than to the woman. The wives of the male irezumi, Ms. Fellman suggests, experience that erotic displacement. It is not unlike the fetishist's need to interpose a symbol—fur or leather, garter belt or high-heeled shoes—between himself and his naked lover. Both fetishism and irezumi are largely the preserve of men; but also of magical and creative power: for love can be strengthened by the conjunction of a symbol.\ Still, it would not surprise me if, for most irezumi, the deepest relationship is with the master, so tirelessly penetrating them.\ I, a writer, an improvisor with words, envy and admire these artists who can bring their work, each day, to a point of completion. Not for them the wastepaper basket, piled high with rejected drafts; they cannot rip off the patch of skin and say, "We'll begin again." Each session must produce the equivalent of a perfect haiku, in which the ephemeral and the universal touch. Do the tattoo masters ever experience the despair of Western artists when things will not go right? Or that rending of the spirit described by Yeats: "The intellect of man is forced to choose/Perfection of the life or of the work"? I suspect they do not. I wish I knew their secret. Sandi Fellman's book does not and could not provide the answer; but it has made me more aware of the question—and of other, equally fascinating, questions—and I am grateful.

Introduction by D. M. Thomas Spirituality and the Flesh: The Japanese Tattoo The Plates Acknowledgments A Note about the Camera List of Plates

\ Library JournalAmerican photographer Sandi Fellman used a rare large size Polaroid camera to create these photos of Irezumi Japanese men and women who wear elaborate full-body tattoos. Fellman treats the tattoos as artworks and their creators as artists. Her text touches on the tattooing process, common motifs, the sociology of the tattoo, and relationships between the tattoo masters and their clients. Author D.M. Thomas has contributed two pages of his reactions to these unusual and even disturbing images. The 46 color plates in this volume, most of them whole body nudes, should prove provocative, fascinating, or repellant to a wide variety of library patrons. Kathryn W. Finkelstein, M.L.S., Cincinnati\ \