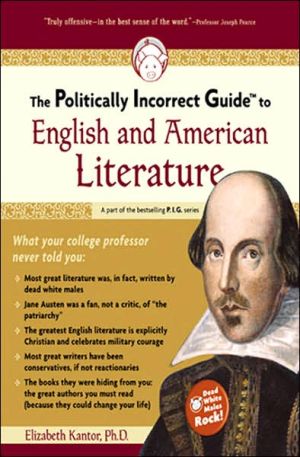

The Politically Incorrect Guide to English and American Literature

What PC English professors don’t want you to learn from: \ \ Beowulf: If we don’t admire heroes, there’s something wrong with us\ Chaucer: Chivalry has contributed enormously to women’s happiness\ Shakespeare: Some choices are inherently destructive (it’s just built into the nature of things)\ Milton: Our intellectual freedoms are Christian, not anti-Christian, in origin\ Jane Austen: Most men would be improved if they were more patriarchal than they actually are\ Dickens: Reformers can do...

Search in google:

The Politically Incorrect GuideT to English and American Literature exposes the PC professors and takes you on a fascinating tour through our great literature-in all its politically incorrect glory. Included: a syllabus and how-to guide to give yourself the English lit education you were denied in school.

The Politically Incorrect Guide to English and American Literature\ \ By Elizabeth Kantor \ Regnery Publishing\ Copyright © 2006 Elizabeth Kantor\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 1-59698-011-7 \ \ \ Chapter One\ OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE The Age of Heroes \ Heart must be the hardier, courage the keener, Spirit the greater, as our strength lessens. -The Battle of Maldon\ English literature begins with Beowulf. Or it used to, before PC professors decided that 1) Heroism is irrelevant to modern life; 2) It's impossible to know the truth about the past (nothing scholars said about Beowulf before the dawn of postmodernism communicates the objective truth about the poem, its author, or the Anglo-Saxon England that it was written in-their understanding of the poem only betrays their agendas); and 3) Studying the Old English language is a waste of graduate students' time, which could, after all, be better employed reading more "literary theory"-Marxism, feminism, and so forth.\ Study of the language Beowulf was written in-Old English (also known as Anglo-Saxon)-was, until quite recently, part of the standard curriculum for serious students of English. Old English is closely related to German, and more distantly to the Scandinavian languages. It was spoken by the barbarian Germanic peoples, known collectively as the Anglo-Saxons, who had conquered and settled England when the Roman Empire was collapsing. Old English is almost entirely opaque tomodern English-speakers, but there are words and sometimes even whole phrases-"þæt wæs god cyning" (that was a good king), for example-that seem to jump off the page to remind you that Beowulf is, after all, written in an earlier incarnation of our own language.\ Students of English literature (even if they didn't plan to become specialists in Old English poetry) used to learn to read Anglo-Saxon. By studying the development of the English language over time, they also used to learn something about the mechanics of all speech: which sounds are made in which parts of the mouth, how the different sounds are physically related to one another. That way, even scholars concentrating in Renaissance drama or Romantic poetry had an acquaintance with the nuts and bolts, as it were, of the English language.\ Beowulf: The hero and the poem\ Eliminating the Old English requirement was one of the first triumphs of the fans of "literary theory" ("deconstruction" and its ilk) in departments of English. Graduate students in English don't read Beowulf as they used to, and they're missing something well worth knowing. Beowulf is full of all kinds of fascinating things, but this is what the central plot boils down to:\ The hero, Beowulf the Geat, travels to Denmark to help Hrothgar, King of the Danes, get rid of a lake-bottom-dwelling monster called Grendel. Heorot, the beautiful hall Hrothgar built, has been unusable (at least at night) since its inaugural feast, when Grendel, disturbed by the music at the celebration, came to the hall, killed thirty warriors, and carried them off to eat. Grendel hasn't left Heorot alone since, and Hrothgar and his wise men have despaired of a solution-until Beowulf arrives. The hero and his men stay the night in Heorot to wait for the monster. Grendel shows up looking for supper, kills and eats one of the Geats, and makes the mistake of grabbing Beowulf for his second course. The monster escapes from the warrior's grip only by leaving one of his arms behind, torn out of its socket at the shoulder. A blood-trail to a lake reveals where Grendel has crept off to die.\ Hrothgar thanks and rewards Beowulf, but it turns out that Heorot still isn't safe. Grendel's mother visits the hall the next night, kills a Dane, and escapes with Grendel's arm. Beowulf goes into the lake after her and kills her with an ancient sword he finds in her lair. Richly rewarded for his deeds, the hero returns to the land of the Geats, where he eventually becomes king.\ Finally, fifty years later, Beowulf kills a dragon that is ravaging the Geatish countryside-but only with the help of a young kinsman; and Beowulf himself is killed in the accomplishment of this last great feat. The Geats burn Beowulf's body and build a tower to house the ashes and the treasures he won from the dragon. Without their great king, the Geats must look forward to defeat at the hands of the many enemies Beowulf kept at bay during his lifetime.\ That's the basic plot, but it's far from being the whole story. Looming behind and peeking around the corners of the main plotline are a number of other stories which give extra depth-whole other dimensions-to the poem. The Beowulf poet (we don't know his name, and we have only guesses about what sort of man he was, and where and when exactly he lived) tells us about a dragonslayer named Sigemund, whose adventure was already an old story in Beowulf's day-and who shows up in Wagner's Ring cycle. He refers to obscure episodes from the wars of the Danes and the Geats with other Germanic peoples: Franks and Frisians, Swedes and Heathobards. The poet sheds light on his characters by comparing them to other figures of history and legend. And he hints at what will happen after the end of the poem. It's foreshadowed, for example, that Heorot will one day be destroyed by fire, and that Hrothgar's sons will be killed by their father's trusted nephew.\ It's a great adventure story, exactly the kind of poem you'd think-if it were in the right professorial hands-would stand a decent chance of turning the thousands of Lord of the Rings movie fans at our nation's universities into aficionados of great English poetry. But English professors approach Beowulf from a great ideological distance. Not many would go as far as John Niles, who flatly denies that Anglo-Saxon England has any reality beyond people's ideas about it. But they do worry that Beowulf is "too masculine and too death-haunted" or otherwise out of step with the world as they see it.\ And no wonder. Beowulf is full to the brim with ideas and attitudes that are exactly opposite to the postmodernist intellectuals' beliefs about the world. The typical English professor hardly wants his students learning the kinds of things you can learn from Beowulf: for example, to admire war heroes, to prefer the tried and true to the trendy and radical, to see Christianity as a powerful civilizing force, and-possibly worst of all-to ask what's wrong with the clever man who hates the warrior (who's a better man than he is).\ Your average college professor is not a great admirer of all things military. He tends to think of soldiers as bloodthirsty killers or deluded dupes. And Beowulf is one long hymn of praise for the warrior. It's also-which may be even worse, from the look-down-your-nose-at-those-ROTC-idiots point of view-a defense of the necessity of military heroism.\ Beowulf takes place in a world that's dangerous, and not just because it's inhabited by monsters and fire-vomiting dragons. The ordinary dangers that fill up the background of the poem-dangers to men from other men-are quite realistic. The circumstances of the remembered historical conflicts may have been changed to make a better story. But real situations in which the choice was kill or be killed were an inescapable feature of life among the ancient Germanic tribes, the ancestors of the Old English.\ The Beowulf poet continually reminds us that peace is fragile; that deadly conflict can break out on any occasion; and that attempts at peacemaking are especially dangerous. For example, as Beowulf explains to his own king on his return from Hrothgar's court, Hrothgar plans to patch up the Danes' feud with the Heathobards by giving his daughter in marriage to a Heathobard prince. Inevitably, as Beowulf predicts, Hrothgar's plan will end in disaster. Violence will erupt when, at the wedding feast, an old Heathobard warrior points out to a young companion that it's his father's sword that some Dane is wearing, and reminds him of how his father died fighting the Danes. The Heathobards won't be able to resist the opportunity for revenge, and the feast will end in more killing.\ The Roman historian Tacitus, writing about the Germanic tribes in the first century A.D., described men like these: warriors whose lives were defined by pride, fidelity, and violence, who measured themselves and one another by their valor in battle and their fierce loyalty to their own. The culture Tacitus described in his Germania has some unique features, but a lot of what he wrote about is common to societies as distant from each other in time and space as the Bronze-Age Greek heroes of Homer's Iliad and the warlike Indians the French and English encountered in North America. In these cultures, which we may call heroic or primitive, men of standing don't do productive work, which is the province of women and slaves. Except for hunting (the leisure activity of the warrior) what the hero contributes to society, his full-time job, is the defense of his own people against other men like himself-or, alternately, the conquest and plunder of other peoples for the enrichment of his own. His other activities, whether singing and competing in drinking contests (among the Germanic tribes) or decorating the backs of his cattle by rubbing ashes into their hair (among the Nuer people that anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard studied in twentieth-century Sudan), are ritual or ornamental.\ But the warrior's defense of his own people by his heroism is not merely decorative; it's absolutely necessary. The strategic insertion of a few conflict resolution experts via time machine would not have changed the dynamics of the heroic age, allowed the ancient Danes and Heathobards to realize that they were irrationally demonizing each other by viewing outsiders as "Other," and ironed the violence out of their culture. Ancient Germanic tribesmen didn't fight because they despised their enemies. When Beowulf talks about the Heathobards who will wreak havoc at the wedding, he considers them not as "Other"-inexplicable, alien, or monstrous-but as great-hearted warriors, too proud to forgo their opportunity for revenge.\ The primitive ancestors of the English fought against men they respected and even identified with-because in the absence of what used to be called civilization there is no way to be sure of freedom, prosperity, or self-respect except to determine to die rather than yield. And, despite what some modern people seem to think, the civilizing element absent from the primitive or heroic society is not the insight that these things simply aren't worth dying and killing for. There were many men living in heroic-age cultures who didn't easily take offense, who didn't consider revenge a duty, and who didn't think their reputations were worth defending with their lives: they were known as slaves.\ The virtues of the heroic age have always been necessary. Wherever and whenever civilization begins to fray among us, you can see the dynamics of the heroic age begin to reassert themselves-as in gang and drug-lord culture, where men risk death and kill for their honor. And we all depend on heroic virtues in our soldiers, to defend our civilization against barbarism from outside.\ Beowulf affirms the two aspects of the heroic life that are most offensive to the modern intellectual: the unavoidable waste of men, and the necessary structure of military command. In Old English poetry, to be lordless is to be hopeless. Beowulf's own death is a disaster because he leaves his people at the mercy of their many enemies. The Geats without Beowulf will be in the fix the Danes are in in the poem's "Finn episode" after their leader Hnæf is slain by the Frisians: forced into a humiliating and untenable subjection to their enemies. Military command is a necessary condition of freedom-and the death of some is necessary for the security of others. As the poet argues after one of Beowulf's companions is killed by Grendel, Grendel would have killed more, if Beowulf's courage (and a wise God) had not prevented that fate.\ But courage in Beowulf is not just something necessary for safety, like burglar alarms, vaccines, or paying your income taxes. Heroism is glorious; it's good in itself; it deserves praise. It's self-evidently valuable-like gold, which is its natural reward. Bravery is preeminent among the things the Beowulf poet continually brings to our attention as deserving our respect. It's the quality that determines the worth of a man. To the extent he has it, he's worthy of praise. To the extent he lacks it, he has to hear the humiliating things that the man who "wants to speak the truth" (wyle so sprecan) must say: Men who are faithless in battle have no reward, no glory, no honor, nothing left but their lives-and they'd be better off dead.\ The Beowulf poet is interested not just in who's brave and who's not, but also in who wants to tell the truth about these things, and who doesn't. The man who wants to speak the truth "in accordance with what is right" (æfter rihte) will distinguish what's good from what's base. He'll recognize nobility wherever he sees it-in the courage and faith of a hero, or in the generosity of a king who rewards warriors with gold. But not everyone tries to know the truth.\ We can only guess what the Anglo-Saxons would have thought of the modern antiwar intellectual, but the Beowulf poet does address a similar phenomenon. Bravery like Beowulf's naturally inspires wonder and praise, telling and retelling. But there is one man in the poem who refuses to acknowledge Beowulf's courage. Hrothgar's courtier Unferth dismisses Beowulf's past exploits and predicts he'll fail against Grendel.\ The Beowulf poet makes it clear that while Unferth's attitude has something to do with one positive capacity the courtier has-his "wit" (a capacity he, interestingly enough, shares with our intellectuals)-the underlying motivation for his grudging attitude is nothing more or less than envy: "It vexed him greatly, the adventure of Beowulf, that High-spirited seafarer. For he did not admit that any other man on earth might ever achieve more glory under heaven than he himself." Unferth attacks Beowulf with words for almost exactly the same reason that Grendel attacks the Danes with his murderous claws. He hates a good that's beyond him. Our intellectuals tend to ask why our soldiers' lives are spent in vain, or who benefits from the glorification of the military hero. The Beowulf poet was interested in a different question: What's wrong with the man who won't give the hero the glory he's earned?\ The Dream of the Rood\ By the time Beowulf was written, the heroic culture of the Anglo-Saxons was being transformed by the civilizing power of Christianity. We're used to thinking of the very first Christians-the disciples Jesus called from their fishing nets-as poor, unlettered men from a provincial backwater of the Roman Empire. But the Apostles were urban sophisticates compared to the Germanic barbarians who invaded the Roman Empire and began to convert to Christianity as it was collapsing.\ There's a story told about Clovis, King of the Franks, that illustrates the almost unbridgeable gap the Germanic tribesmen had to reach across to accept the gospel. Clovis is said to have been much moved when he was first told the story of the Crucifixion. "If I had been there with my Franks," he exclaimed, "I would have avenged His wrongs!" It's hard to think of anything more alien to the Crucifixion as it's portrayed in the New Testament than the duty of revenge among the German tribes. You can make a pretty good case that these barbarians misunderstood Christianity completely. And yet there was something they saw and loved there, not really understanding it; and it changed them. Beowulf is a fruit of that transformation.\ Beowulf's battles are not just the exploits of an ordinary hero in defense of his people against warriors from some other tribe. And they're not the timeless contests of pagan myth, either. Grendel isn't a fairy tale bogey or a mythological monster. When Grendel first appears, the Danes are rejoicing and a poet is singing the story of God's creation. The poet makes clear that Grendel represents the kind of evil you can read about in the Bible. He's descended from Cain, the first murderer. And Cain's murder of his brother was a result of the original disobedience of Adam and Eve, which itself came about because of Lucifer's rebellion against God. Grendel's hostility to men is part of the eternal enmity of mankind's original Enemy.\ And in Beowulf's character there is a glimpse of virtue that transcends the ethic of the heroic age. Behind the hero, you can see the shadowy image of a Man who is stronger, braver, and more patient than any other man, and Who faces death and emerges with a different kind of victory.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Politically Incorrect Guide to English and American Literature by Elizabeth Kantor Copyright © 2006 by Elizabeth Kantor. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ From Barnes & NobleElizabeth Kantor advances a forthrightly politically incorrect view of English and American literature in this guaranteed-to-be controversial guide. Kantor argues that, contrarian to P.C. opinion, most great literature was written by now-dead white Christian males. Definitely a conversation starter.\ \