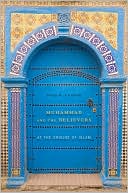

The Quest for the Historical Muhammed

More than one hundred years ago Western scholars began to investigate the origins of Islam, using the highest standards of objective historical scholarship of the time. Their aim was to determine what could be known about Muhammad and the rise of early Islam quite apart from the pious and totally unobjective traditions preserved by the Muslim religious community. In some ways this research was inspired by a similar investigation of Christianity made famous by Albert Schweitzer's Quest of the...

Search in google:

Warraq, best known as the author of , assembles 15 studies applying western standards of history to the Prophet and the origins of Islam, ranging from the early 19th century to the end of the 20th. Among the questions they raise are whether the Koran was dictated by Muhammed at all or even compiled earlier than a hundred years after his death, whether much of Muslim sacred tradition must be dismissed as hearsay, and whether the Jihad was largely a religious or a mercenary undertaking. The anthology is not indexed. Annotation c. Book News, Inc., Portland, OR Publishers Weekly Warraq, author of Why I Am Not a Muslim, here offers a "quest for the historical Muhammad" using the same methodology established by scholars attempting to uncover the historical Jesus. Applying this approach to determine if early traditions about Muhammad and the birth of Islam are historically accurate, Warraq predictably finds that the faith tradition cannot support the historian's demanding gaze. For example, Warraq argues that the centrality of Muhammad himself (as the prophet of God, author of the Qu'ran and focal point of Islamic culture) did not emerge until at least two centuries after the death of the historical Muhammad. Warraq's subtext is significantly unlike the Jesus Seminar's similar work, in which historians who are also Christians struggle to sort out the ways that historical methodology may illuminate and enliven the faith tradition. As his earlier titles suggest, this is not the work of a Muslim in radical dialogue with his faith. Under the guise of scholarly objectivity, Warraq wages a vigorous attack on the traditions of Islam. Biases notwithstanding, there is also much useful scholarship here; not only has Warraq provided a highly readable critical survey of the literature of this quest, he has also collected the most important texts needed to begin a more objective evaluation of Islam's sacred tradition. The reader's task is to sort the polemic from the scholarship. (Mar.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\|

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Studies on Muhammad\ and the Rise of Islam\ \ A Critical Survey\ Ibn Warraq\ * * *\ \ \ Ernest Renan believed that, "in place of the mystery under which the other religions have covered their origins [Islam] was born in the full light of history; its roots are on the surface. The life of its founder is as well known to us as that of any sixteenth-century reformer. We can follow year by year the fluctuations of his thought, his contradictions, his weaknesses" (see page 110 in this volume). This view has been vigorously attacked by formidable modern scholars, whose conclusions are lucidly presented by Ibn Rawandi in his following essay, "Origins of Islam: A Critical Look at the Sources." The other essays equally cast doubt on the reliability of the Muslim sources, that Renan, and in more recent years, Montgomery Watt, have taken at their face value; indeed, this whole anthology can be seen as an implicit criticism of this optimistic view of our historical evidence for the rise of early Islam. Renan's views are still shared by some scholars and laymen alike. Here is how Salman Rushdie, echoing Renan's very words, voiced a very common opinion:\ \ \ And what seemed to me to be really interesting was that [Islam] was the only one of the great world religions that existed as an event inside history. You couldn't say that about Christianity, because our records of Christianity date from about a hundred years after the events they represent. It's a really long time. The degree of authority one cangive to the evangelists about the life of Christ is relatively small. Whereas for the life of Muhammad, we know everything more or less. We know where he lived, what his economic situation was, who he fell in love with. We also know a great deal about the political circumstances and the socioeconomic circumstances of the time.\ \ \ One of Renan's achievements was to liberate scholars and enable them to freely "discuss the origins of Christianity as dispassionately and as `scientifically' as those of any other religion." And it is with supreme irony that we read today his preface to the thirteenth edition of The Life of Jesus (1867), where he pleads for the right to examine scientifically the Gospels, the same right that, he claims, Islamologists avail themselves of when examining the Koran and the Hadith; or when we read in L'Avenir de la Science (The Future of Science, 1890), where he hopes the day will arrive when writing a history of Jesus will be as free as the writing of the history of Muhammad!\ Of course, Renan is interesting in his own right as a historian of religion. The present essay in this volume, the first English translation, was written in 1851, twelve years before his more celebrated Life of Jesus. Renan is an infinitely more subtle and sensitive thinker than the rather racist bigot presented to us by certain "antiorientalist" writings. Those who expect to find only rationalist mockery or Voltairean skepticism will be surprised to discover instead "reverence towards religion, a sensitivity to legends, sympathetic awareness of the perennial human need for faith." A shallowness in his own capacity for belief did not preclude a profundity of religious understanding and knowledge.\ Renan, not uncritical in his attitude to the Muslim sources, was able to appreciate the difference between "the historical value of the chronicles of the Arab historians and the collection of legends spawned by the Persian imagination" (see page 130 in this volume). Nearly thirty years before Goldziher's pioneering research on the Hadith, Renan was able say that, although Bukhari himself had reduced 20,000 Hadith to just 7,225 that seemed to him genuine, "without being accused of recklessness, European criticism could assuredly proceed to an even more strict selection." Similarly, Renan says of the Koran, "the integrity of a work committed to memory for a long time is unlikely to be well preserved; could not interpolations and alterations have slipped in during the successive revisions?" Having made these token gestures of skepticism, Renan in the end accepts the Muslim accounts on their own terms: "However, it cannot be denied that these early accounts show a lot of features of the true character of the Prophet, and are distinguished, in a clear-cut manner, from the collection of pious stories solely imagined for the edification of their readers. The veritable monument of the early history of Islam, the Koran, remains absolutely impregnable, and suffices in itself, independently of any historical accounts, to reveal to us Muhammad.... [N]othing could attack the broad authenticity of this book [the Koran]."\ Basing himself on these Muslim sources, Renan then proceeds to draw an exceedingly favorable portrait of the Prophet, while recognizing his moral failings: "On the whole, Muhammad seems to us like a gentle man, sensitive, faithful, free from rancor and hatred. His affections were sincere, his character in general was inclined to kindness.... Neither ambition nor religious rapture had dried up the personal feelings in him. Not at all akin to this ambitious, heartless and machiavellian fanatic [depicted by Voltaire in his drama Mahomet]." Renan is at pains to defend Muhammad from possible criticisms: "As to the features of the life of Muhammad which, to our eyes, would be unpardonable blots on his morality, it would be unjust to criticize them too harshly.... It would also be unjust to judge severely and with our own considered ideas, the acts of Muhammad, which in our days would be called swindles." The Prophet was no imposter, Renan asserts: "It would be to totally lack a historical sense to suppose that a revolution as profound as Islam could be accomplished merely by some clever scheming, and Muhammad is no more explicable by imposture and trickery than by illuminism and religious fervor." Being a religious humanist, Renan valued Islam, and religion in general, "because it manifested what was divine in human nature," and seemed to answer the deepest instincts of human nature; in particular it answered the needs of seventh-century Arabia, an idea taken up in modern times by Montgomery Watt.\ In adumbrating Renan's thought on religion in general and Islam in particular, I do not wish to necessarily endorse everything he says. Indeed, I do not find his analyses always compelling or correct. Renan contradicts himself when he tells us that Islam somehow answered the needs of seventh-century Arabia while at the same time insisting that "I do not know if there is in the entire history of civilization a spectacle more gracious, more attractive, more lively than that offered by the Arab way of life before Islam ... unlimited liberty of the individual, complete absence of law and power, an exalted sense of honor, a nomadic and chivalrous life, humour, gaiety, roguishness, light, impious poetry, courtly love." Why bring Islam into this idyllic picture then? Renan tells us that, even after the arrival of Islam, outside a small group of Arabs, there was nothing particularly religious about the movement. As Patricia Crone has argued, "the fact is that the tradition knows of no malaise in Mecca, be it religious, social, political or moral. On the contrary, the Meccans are described as eminently successful; and Watt's impression that their success led to cynicism arises from his otherwise commendable attempt to see Islamic history through Muslim eyes." As for the spiritual crisis, there was no such thing in sixth-century Arabia. Islam was successful because it offered the Arabs material rewards in the here and now—military conquests with all the attendant material advantages: loot, women, and land.\ \ \ Otherwise, Renan's essay is full of insights and pithy sayings like the following:\ \ \ Persecution, in effect, is the first of the religious pleasures; it is so sweet to the heart of man to suffer for his faith, that this attraction suffices sometimes to make him believe. This is what Christian consciousness has wonderfully grasped in creating these admirable legends where so many conversions take place through the charm of torture. (See p. 158 in this volume.)\ \ \ If the zeal of an imperious temperament clinging frantically to dogma, in order to hate at his leisure, must be called faith, then `Umar [the Second Caliph, 634 C.E.] really was the most energetic of believers. No one has ever believed with more passion, no one has ever got more angry in the name of the unquestionable. The need to hate often leads loyal, crude, and unsubtle characters into faith, for absolute faith is the most powerful pretext for hatred, the one to which one can abandon oneself with the clearest conscience. (See p. 141 in this volume.)\ \ \ We end these reflections on Renan by noting some of his views that are surprisingly modern. Renan remarks that all the dogmas of the Muslim creed floated in uncertainty right up to the twelfth century, a thesis developed with extraordinary rigor by John Wansbrough in modern times. Renan concludes his essay with the following observation:\ \ \ It is superfluous to add that if ever a reformist movement manifests itself in Islam, Europe should only participate in it by the influence of a most general kind. It would be ungracious of her to wish to settle the faith of others. All the while actively pursuing the propagation of her dogma which is civilization, she ought to leave to the peoples themselves the infinitely delicate task of adjusting their own religious traditions to their new needs; and to respect that most inalienable right of nations as much as of individuals, the right to preside oneself, in the most perfect freedom, over the revolutions of one's conscience. (See pp. 163-64 in this volume.)\ \ \ These are hardly the words of a cultural imperialist. Nor does Renan believe that Islam is unchanging or essentially incapable of changing: "Symptoms of a more serious nature are appearing, I know, in Egypt and Turkey. There contact with European science and customs has produced freethought sometimes scarcely disguised. Sincere believers who are aware of the danger do not hide their disquiet, and denounce the books of European science as containing deadly errors, and subversive of all religious faith. I nevertheless persist in believing that if the East can surmount its apathy and go beyond the limits that up to now it was unable to as far as rational speculation was concerned, Islam will not pose a serious obstacle to the progress of the modern mind. The lack of theological centralization has always left a certain degree of religious liberty to Muslim nations."\ However, Renan's views never remained immutably fixed; to think that he had just one set of monolithic beliefs obstinately held throughout his career is just the very "orientalist" attitude that certain "antiorientalists" accuse Renan of. During his visits to the Middle East, in 1860 to 1861 and later in 1865, Renan witnessed what he felt was the moral, cultural, and scientific stagnation of Muslims, and his ideas changed accordingly; Renan now felt it was one's duty to liberate Muslims from Islam, to which he attributed all their backwardness in his lecture Islamisme et a Science given in 1883:\ \ \ Muslims are the first victims of Islam. Many times I have observed in my travels in the Orient that fanaticism comes from a small number of dangerous men who maintain the others in the practice of religion by terror. To liberate the Muslim from his religion is the best service that one can render him.\ \ \ The rights established by Renan and other nineteenth-century European scholars to examine critically and scientifically the foundations of Islam—whether of the Koran or the life of the Prophet—have been squandered in a welter of ecumenical sentimentality resulting in a misplaced concern for the sensibilities of Muslims. For instance, very recently in an essay entitled "Verbal Inspiration? Language and Revelation in Classical Islamic Theology," Professor Josef van Ess expressed his respect for the tender susceptibilities of Muslims by stopping, being a non-Muslim himself, his critical analysis out of respect for the way that Sunni Islam treats the history of thought! Mohammed Arkoun very sensibly replied that such an attitude was unacceptable scientifically, for historical truth concerns the right of the human spirit to push forward the limits of human knowledge; Islamic thought, like all other traditions of thought, can only benefit from such an epistemological attitude. Besides, continues Arkoun, Professor van Ess knows perfectly well that Muslims today suffer from the politics of repression of free thought, especially in the religious domain. Or to put it another way, we are not doing Islam any favors by shielding it from Enlightenment values.\ I have already noted how and why western scholarship has moved from objectivity to Islamic apologetics pure and simple; a trend remarked in 1968 by Maxime Rodinson:\ \ \ In this way the anticolonialist left, whether Christian or not, often goes so far as to sanctify Islam and the contemporary ideologies of the Muslim world.... A historian like Norman Daniel has gone so far as to number among the conceptions permeated with medievalism or imperialism, any criticisms of the Prophet's moral attitudes, and to accuse of like tendencies any exposition of Islam and its characteristics by means of the normal mechanisms of human history. Understanding has given way to apologetics pure and simple.\ \ \ Professor Montgomery Watt has been taken to task in recent years by scholars for his overoptimistic attitude to the Islamic sources of the history of early Islam. Their arguments against Watt have been superbly summarized below by Ibn Rawandi. I, however, have severely criticized Watt for other reasons: for his protective and ultimately patronizing and insincere stance to Islam and Muslims, a position that goes beyond dispassionate scholarship and veers between Islamic apologetics on the one hand and condescension on the other. Watt's bad faith (mauvaise foi) is in evidence when he writes in the preface to his celebrated biography of Muhammad, "in order to avoid deciding whether the Koran is or is not the Word of God, I have refrained from using the expressions `God says' and `Muhammad says' when referring to the Koran, and have simply said `the Koran says.'"\ Bernard Lewis has remarked that such measures have tended to make the discussions of modern orientalists "cautious and sometimes insincere." That is putting the matter kindly. Professor Watt is a devout Christian, an ordained priest, in fact, who does not believe that the Koran is the Word of God. But the curious fact is that this maneuvering has not endeared him to thoughtful Muslims, who ask why Watt obstinately refrains from converting to Islam if it is such a wonderful religion as he claims. The irony of a Christian cleric apologizing for the most anti-Christian of religions is not missed by the Muslims. Here is what Hussein Amin, an Egyptian intellectual, diplomat, and liberal practicing Muslim, has to say about Watt:\ \ \ Watt defends Islam and her Prophet better than the most zealous Muslims.... However, in our opinion, there is in his position a profoundly incomprehensible contradiction, such that we prefer in certain ways the biography by Muir, which has the advantage of honestly coming out in its true colors.\ \ \ Hussein then quotes several examples of Watt's rather dishonest attempts to ingratiate himself with Muslims—the maneuvering referred to above. Hussein ends with the following quote from Watt and then comments on it:\ \ \ With the greatly increased contacts between Muslims and Christians during the last quarter of a century, it has become imperative for a Christian scholar not to offend Muslim readers gratuitously, but as far as possible to present his arguments in a form acceptable to them. Courtesy and an eirenic outlook certainly now demand that we should not speak of the Koran as the product of Muhammad's conscious mind; but I hold that the same demand is also made by sound scholarship.\ Despite all our admiration for the works of W. Montgomery Watt, this position seems to us, in a word, incomprehensible and unacceptable. First of all why should there be a connection between the present development of links between Islam and the West, and the necessity for the Westerners to judge the Prophet fairly, even to exalt his merits, ...? If there is in Europe a mounting interest in the Arab cause, which is evident for example in the proliferation of Islamic cultural festivals, or in the relatively large number of copies printed of contemporary Arab writers, perhaps we shall soon be studying the impact of the global energy crisis on the writing of the biography of the Prophet in oil-consuming countries!\ All that is, in the end, not very surprising. On the other hand what is more surprising, and which grieves us more deeply, is to see Muslims besottedly applauding any old Western author, including those without a specialist knowledge of Islam such as Gustave le Bon or Carlyle, who defends the Prophet, and inversely, take exception to those who denigrate him. There is nothing to be proud of in the praise of the former, nor any reason to get excited about the calumnies of the latter. Why be proud of praise which results more often from the atheism of the author and his desire to shock his compatriots, to prove his independence of thought or his objectivity, even to safeguard his material interests or to draw closer to the Muslim states ...?\ The moment has come for Muslims to write a new biography of the Prophet ... which does not leave out "that which could offend certain readers.\ \ \ No, Muslims do not need patronizing liberals to meet them "halfway"! Muslims need to write, for example, an honest biography of the Prophet that does not shun the truth, least of all cover it up with the dishonest subterfuge of condescending Western scholars. However, as Rodinson points out, writing in 1963, most Muslim biographers of the Prophet lack any critical sense whatsoever: "Numerous works in Arabic appear each year evidencing blind confidence in sources that are several centuries later than the events which they report. The accounts found in our Muslim sources of events which occurred at the beginning of Islam do indeed require special methodological study, for the process of oral transmission constitutes a problem whose implications have not yet been fully explored." But, as Rodinson hastens to add in a footnote, this "is in no way a question of an incapacity congenital to the `Arab spirit.' Many contemporary Arab authors have given us excellent historical studies and remarkable critical editions which in all points conform to the rules of historical and philological method. However, in the present state of affairs and for precise sociological reasons, the biography of Muhammad is a subject that is taboo and is permitted only when written as apologetic and edifying literature."\ Rodinson gives us an admirable survey of the writings of Arab scholars, which are quite worthless from the scientific point of view: "[F]or complex sociological reasons, the larger part of [the] educated bourgeois public [in the Middle East] rejected the scientific enthusiasm of the preceding generation and returned to the faith of the ancestors. This explains the immense popularity of the biography of the Prophet published in 1935 by the writer and politician, Muhammad Husain Haykal.... In an easy and modern style, Haykal retraces the life of the Prophet, writing a `scientific study according to the modern western method'" (5th ed., p. 18). But if this "scientific method" leads him to reject a certain number of miracles attributed (at a late date) to the Prophet and to interpret some of them in "natural" fashion, it also leads him to affirm the foundations of the Muslim faith. He undertakes a critical study of the sources but only for the purpose of attacking certain narratives preserved by Muslim tradition that appear offensive to the modern conception of the Prophet. It is a skillful reconstruction of the life of Muhammad suited to the needs of a modern apologetic, "but it is far from being scientific in its viewpoint." In an even more damning footnote, Rodinson specifies all the shortcomings of Haykal's decidedly unscientific methodology; "one might mention as typical passages the attack on the narrative of the `satanic verses' inspired in Muhammad by the devil" (Haykal, pp. 160-67), and the reconstruction of the history of the "revolt" of the wives of the Prophet (pp. 447ff.). The work is interspersed with discussions that are purely apologetic and with attacks against "the Orientalists" of whom he mentions only the popular work of Dermenghem and especially the work of the American author, Washington Irving, written in 1849. Occasionally, there are opportune silences, as, for example, the murder of Ka'b b. al-Ashraf (pp. 278ff.); he passes over in silence the incitement to murder by Muhammad (Ibn Hisham, p. 550). There are even some falsifications: according to Haykal [p. 339], the Jews of Qurayza chose "as though they were blinded by fate" the arbiter Sa'd b. Mu'adh who was going to decide in favor of their massacre; however, according to the early sources it was Muhammad who made that decision."\ Rodinson continues his survey of Arabic works: "At about the same time, the Egyptian savant, Ahmad Amin [father of Hussein Amin, discussed above], in a book entitled Fair al-Islam (the Dawn of Islam, Cairo, 1929) commenced an extensive history of Arab and Muslim civilization. However, he carefully avoided the difficult and dangerous area of the biography of the founder." The Egyptian man of letters, Taha Husain, had got into a great deal of trouble in 1926 for his work, Fi'sh-Shi'r al-Jahili, in which he questioned the historical veracity of the Koran. Charged with blasphemy, he was forced to withdraw his book, and lost his university post. But in 1933, "Taha Husain quickly came around to a less threatening approach; following the literary style of Jules Lemaitre, he wrote delightful narratives in the margin of the sira (the traditional life of Muhammad) [in Ala Hamish as Sira, Cairo, 1933] The talented essayist Abbas Mahmud al-Aqqad, a man of fascist sympathies, assumed the apologetic stance in a more virulent, 'updated' manner, but also with less caution. From the scientific point of view one may disregard such works." The one exception seems to have been the Arab Marxist, Bandali Jawzi, who "did raise the question of the historical forces at work in the rise of Islam, and he did so without recourse to the principle of divine intervention."\ Rodinson was writing of the twenties and thirties, but unfortunately things have not improved a great deal, as can be seen by the embarrassment caused in Cairo in the 1980s by Hussein Amin himself with his gentle but courageous skepticism. Nothing could illustrate with greater irony the fact that not much has changed for the better since Rodinson wrote his survey in 1963 than the fate of Mohammed, the celebrated biography of the Prophet by Maxime Rodinson himself, first published in 1961. Despite the fact that Rodinson's very conventional biography has been available in Egypt for over twenty years, it was withdrawn in May 1998 from the curriculum of the American University in Cairo's History of Arab Society course after complaints from a newspaper columnist, Salah Muntaser of the government-run newspaper, Al-Ahram, and the ministry of higher education. According to the Minister, Mufeed Shehab, the book contained "fabrications harmful to the respected prophet and to the Islamic religion," even though Rodinson had grounded his work solidly and entirely on Muslims sources. Rodinson had upset Muntasser by suggesting that Muhammad had been influenced by Jews and Christians, and by explicitly avowing that he (Rodinson) did not believe the Koran was the word of God. Perhaps Muntasser had in mind the following passage in Rodinson's work: "May any Muslims who happen to read these lines forgive my plain speaking. For them the Koran is the book of Allah and I respect their faith. But I do not share it and I do not wish to fall back, as many orientalists have done, on equivocal phrases to disguise my real meaning. This may perhaps be of assistance in remaining on good terms with individuals and governments professing Islam; but I have no wish to deceive anyone. Muslims have every right not to read the book or to acquaint themselves with the ideas of a non-Muslim, but if they do so, they must expect to find things put forward there which are blasphemous to them. It is evident that I do not believe that the Koran is the book of Allah."\ While Rodinson is to be commended for his frankness, his statement quoted above amounts to an apology, and I wonder if he has entirely avoided a certain moral ambiguity in his position, rather like the health warnings on packets of cigarettes. In any case, his position has not done his work any good in Egypt.\ \ \ THE SOURCES AND THEIR RELIABILITY\ \ \ A. Literary Sources: Sira and Maghazi\ \ \ If we were to examine Fuat Sezgin's History of Arabic Literature, we would get a falsely optimistic picture of the sources for the history of pre-Islamic Arabia, the life of Muhammad, and the rise of Islam and its history up to the year 1000 C.E., since Sezgin gives the name of some seventy historians. Alas, the writings of these historians are not extant, and we only know them through quotations of them by later historians.\ Our knowledge of early Islam and its founder rests on the writings we call sira and al-Maghazi, and also the Koran, Koranic exegesis (tafsir), and the Hadith (the traditions).\ Sira, in our context, means "biography" or "the life and times of." "The sira," sirat rasul allah or al-sira al nabawiyya have been the most commonly used names for the traditional account of the Prophet's life and background. Sira even came to mean, in the end, the account of Muhammad's life and background as transmitted by Ibn Hisham on the basis of the work by Ibn Ishaq.\ According to the definition in the Encyclopedia of Islam, second edition, "al-maghazi (also maghazi `l-nabi, maghazi rasul allah), a term which, from the time of the work on the subject ascribed to al-Waqidi (d. 207/823), if not earlier, has signified in particular the military expeditions and raids organized by the Prophet Muhammad in the Medinan period." But this term in the end also acquired a broader sense and seems to have been used more or less synonymously with the term sira.\ Stefan Leder has usefully summarized the several fields of Arabic literature that deal with early Islamic history, and introduces us to the various Arabic terms that we use in this domain, which are indispensable for any understanding of Muslim historical writing:\ \ \ Prophetic tradition (Hadith), which contains countless reports about sayings and deeds of Muhammad; Koranic commentaries (tafsir), where revelation is related to the life of the Prophet; historiography, and finally adab literature, which displays the ideal of refinement and unites entertaining and didactic tendencies.\ Historiographical literature about early Islamic times is divided mainly according to historical periods. Material on the life of the Prophet (sira), the military campaigns directed by the Prophet or his Companions (maghazi), and the conquests (futuh), as well as particular cases (waqa, maqtal) are kept distinct, although not entirely separate. Biographically organized works (tabaqat) and collections of hadith may include all of these materials. Narratives about the pre-Islamic battle-days (ayyam al-arab) are often considered to be the predecessors of and model for Arabic historiographical narration; this seems questionable, however, since the extant textual evidence cannot claim an origin prior to other branches of literature about early Islamic times.\ The historiographical and biographical compilations, works on poets and poetry, and those which treat linguistic matters, are to a great extent compilations of short texts. These include simple statements, utterances of authoritative scholars, saints, or statesmen, reports of events, and—sometimes rather complex—stories about historical events and personalities. These texts, which may vary in length from one line to several pages are designated by the term khabar (pl. akhbar [akhbari pl. akhbariyun = the collector and/or compiler of akhbar]).\ \ \ Here it would perhaps be appropriate to include the terms qussas and qisas. Qisas denotes particularly the genre of tales and myth relating to the prophets of the Koran or the Old Testament, but is also used to designate other stories that indulge in dramatic effects and colorful descriptions, all derived from the style of popular storytellers, qussas.\ I shall be begin with a list of the most prominent historians giving both their Islamic (A.H.) and Common Era dates, for this enables us to see immediately how near, or more frequently, how far they are from the events they describe.\ 1. Aban b. `Uthman al-Bajali (ca. 20/640-100/718). He was the son of the murdered caliph `Uthman, and took part in the campaign against his father's slayers. He seems to have written a book on maghazi, which has not survived. Neither Ibn Ishaq nor al-Waqidi cite him.\ 2. `Urwa b. al-Zubayr b. al-Awwam (23/643-94/712). He was a cousin of the Prophet, and considered an authority on the early history of Islam. It is uncertain whether he wrote a book, but there are many traditions that have been handed down in his name by Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Sa'd, and al-Tabari. For this reason he is often referred to as the founder of Islamic history.\ 3. Shurabil b. Sa'd (d. 123/740). Little is known about him, though it appears he wrote a maghazi book. However, many later writers considered him unreliable and thus he is seldom quoted.\ 4. Wahb b. Munabbih (34/654-110/728). He seems to have been a South Arabian of possibly Persian origin with a deep knowledge of Jewish and Christian scriptures and traditions. Wahb wrote the Kitab al-Mubtada, which inspired many Muslim versions of the lives of the prophets. However, much was attributed to him for which he was not responsible. Wahb collected the maghazi, and this has been confirmed by the discovery of a fragment of the lost work on papyri written in 228/842, the so-called Heidelberg papyrus. Wahb himself did not know of the use of isnads, that is the chain of transmitters of a particular tradition. Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Sa'd, al-Tabari, and al-Waqidi do not use Wahb for the life of the Prophet but for the beginnings of Christianity in South Arabia.\ 5. Asim b. `Umar b. Qtada al-Ansari (d. ca. 120/737). He lectured in Damascus on the maghazi of the Prophet and his Companions, and probably committed his lectures to writing, though this is much disputed by skeptics who point out that this claim is based on later writings. He does not always cite his authorities or isnads. Ibn Ishaq seems to have attended al-Ansari's lectures.\ 6. Muhammad b. Muslim b. Shihab al-Zuhri (51/671-124/741). He was a member of a distinguished Meccan family of Zuhra, of which he wrote a history. He is sometimes credited with a book of maghazi, but Zuhri's compilations were probably confined to collections of traditions of the Prophet and his companions of which he very assiduously collected a vast number. His students took down notes of his lectures which have survived; Ibn Ishaq often cites him as an authority. However, skeptics point out that the claim that Zuhri used writing are based on later historians, and thus cannot be accepted uncritically.\ 7. Abdullah b. Abu Bakr b. Muhammad b. `Amr b. Hazm (d. 130/747 or 135/752). He was one of Ibn Ishaq's most important informants. There is no evidence of any book by Abdullah, and he does not seem to have bothered with isnads when passing down traditions to his hearers.\ 8. Abu'l-Aswad Muhammad b. `Abdu'l-Rahman b. Naufal (d. 131/748 or 137/754). He wrote a book of maghazi that seems to remain faithful to Urwa b. al-Zubayr in its essentials.\ 9. Musa b. `Uqba (ca. 55/674-141/758) A fragment of his work has survived and was published by Sachau in 1904, the so-called Berlin manuscript. Many distinguished traditionists felt his book was the most important and trustworthy of all, rivaling that of his contemporary Ibn Ishaq, and yet, surprisingly, not much of his work has survived. Ibn Ishaq himself never mentions him, though he is quoted by later historians like al-Tabari, al-Waqidi, and others. Musa for his part leaned heavily on al-Zuhri, much idealizing the Prophet.\ 10. Ibn Ishaq (ca. 85/704-150/767). He is one of our main authorities on the life and times of the Prophet. His family was involved in transmissions of Hadith and Ibn Ishaq followed suit. He left Medina where he was born for good, probably because of the enmity of certain people like the traditionist Malik b. Anas; he eventually settled in Baghdad. Apart from the Sira he is also credited with a Kitab al Khulafa (sometimes called Ta'rikh al-khulafa'—A History of the Caliphs) and a book of Sunan. His reputation seems to have varied considerably among the early Muslim critics; some found him very sound (e.g., al-Zuhri, who spoke of him as "the most knowledgeable of men in maghazi"), while others regarded him as a liar in relation to Hadith (e.g., al-Athram, Sulayman al-Taymi, and Wuhayb b. Khalid). However, it is of the utmost importance to realize that the Sira of Ibn Ishaq is not extant in its original form, and is not preserved as a single work. It has been preserved in two recensions, one by Ibn Hisham (d. 218/833; see below) and another by Yunus b. Bukayr (d. 199/814-815); each text seems to vary from the other. Other parts of Ibn Ishaq's work have been quoted by Muhammad b. Salaam al-Harrani (d. 191/807) and thirteen other students, compilers, and historians who had heard his lectures in various towns like Medina, Kufa, Basra, and so on. Thus, the lost original of Ibn Ishaq's work has to be restored or recovered from at least fifteen different versions, excluding that of Ibn Hisham (with the towns where the individuals heard Ibn Ishaq's lectures:\ a. Ibrahim b. Sa'd, 110/728-184/800, Medina\ b. Ziyad b. `Abdullah al-Bakkai, d. 183/799, Kufa\ c. `Abdullah b. Idris al-Audi, 115/733-192/807, Kufa\ d. Yunus b. Bukayr, d. 199/815, Kufa\ e. `Abda b. Sulayman, d. 187/802 or 188/803, Kufa\ f. `Abdullah b. Numayr, 115/733-199/814, Kufa\ g. Yahya b. Said al-Umawi, 114/732-194/809, Baghdad\ h. Jarir b. Hazim, 85/704-170/786 Basra\ i. Harun b. Abu'Isa, Basra?\ j. Salama b. al-Fadl al-Abrash, d. 191/806, Ray\ k. Ali b. Mujahid, d. ca. 180/796, Ray\ l. Ibrahim b. al-Mukhtar, Ray\ m. Sa'id b. Bazi\ n. `Uthman b. Saj\ o. Muhammad b. Salama al-Harrani; d. 191/806\ \ These facts have led many scholars to conclude that "there has hardly been any written standard text by Ibn Ishaq himself and that we depend on his transmitters, whose texts should be studied synoptically, in all their variants." Sell-heim, on the other hand, has tried to discern three layers of sources in Ibn Ishaq, an original layer reflecting historical reality, a second layer reflecting legendary material about the Prophet, and a top layer reflecting the political tendencies of Ibn Ishaq's own time. Passages left out by Ibn Hisham in his edition have been quoted by later historians like al-Tabari, al-Azraki, and at least ten others. Ibn Ishaq placed the Prophet Muhammad in the tradition of the earlier prophets, which makes him the pivot of world history by adding a history of the caliphs.\ 11. Ma'mar b. Rashid (d. 154/770). His Kitab al-Maghazi is preserved within the Musannaf of Abd al-Razzak b. Hammam al-San'ani (126/744- 211/827). Rashid gathered much of his material from al-Zuhri.\ 12. Abu Mikhnaf Lut b. Yahya `l-Azdi (d. 157/774). He is said to have written over thirty historical treatises, and much of his work is quoted by both al-Tabari and Baladhuri. But many writings that were attributed to him are now known to be later forgeries.\ 13. Sayf b. `Umar (d. ca. 180/796). He was al-Tabari's principal source for the early Arab conquests and the history of the Caliphate down to the death of `Ali. The great German scholar, Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918) wrote a devastating critique of Sayf's work in his Prolegomena zur altesten Geschichte des Islams (1899), and Sayf's reputation has not been high ever since. Wellhausen places Sayf in what he calls the "artificial" tradition of Arab historical writing, which was full of "tendentious distortions and fictitious tales invented for their literary impact."\ 14. Yunus b. Bukayr (d. 199/815). As noted above, Yunus is important for his recension of Ibn Ishaa's work, though his version differs from the familiar versions. But what is often forgotten is that Yunus "transmitted materials which do not go back to Ibn Ishaa at all. Yunus was a sira compiler in his own right, whose Ziyadat al-Maghazi was quoted by al-Bayhaki Ibn Kathir and several others."\ 15. Ibn Hisham (d. 218/833 or 213/828). Born in Egypt, he spent his entire life there. Although he wrote a book on South Arabian antiquities, Kitab al-Tidjan, that has survived down to our times, Ibn Hisham is, of course, more famous for his edition of the Sira of Ibn Ishaq. Ibn Hisham derived his knowledge of the latter's work from Ziyad al-Bakka'i (d. 183/799), a pupil of Ibn Ishaq who lived mostly in Kufa, but may have travelled to Iraq to study. Al-Bakkai made two copies of Ibn Ishaq's work, one of which reached Ibn Hisham, "whose text, abbreviated, annotated, and sometimes altered, is the main source of our knowledge of the original work."\ 16. Al-Waqidi (130/747-207/822-23). He wrote over twenty works of a historical nature, but only the Kitab al-Maghazi has survived as an independent work. Waqidi's authorities include Musa b. `Uqba, and he made extensive use of Ibn Ishaq's work. He was a Shiite, and his zeal for `Ali is revealed in the details in his history. He is especially important for having established the chronology of the early years of Islam. He is frequently cited by al-Tabari, who also relied upon him for variant narratives. Both Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi's reputations have suffered in recent years as a consequence of the trenchant criticisms by Patricia Crone, especially in Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, pp. 203-30), where she argues that much of the classical Muslim understanding of the Koran rests on the work of storytellers and that this work is of very dubious historical value. These storytellers contributed to the tradition on the rise of Islam, and this is evident in the steady growth of information: "If one storyteller should happen to mention a raid, the next storyteller would know the date of this raid, while the third would know everything that an audience might wish to hear about it." Then, comparing the accounts of the raid of Kharrar by Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi, Crone shows that al-Waqidi, influenced by and in the manner of the storytellers, "will always give precise dates, locations, names, where Ibn Ishaq has none, accounts of what triggered the expedition, miscellaneous information to lend color to the event, as well as reasons why, as was usually the case, no fighting took place. No wonder that scholars are fond of al-Waqidi: where else does one find such wonderfully precise information about everything one wishes to know? But given that this information was all unknown to Ibn Ishaq, its value is doubtful in the extreme. And if spurious information accumulated at this rate in the two generations between Ibn Ishaq and al-Waqidi, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that even more must have accumulated in the three generations between the Prophet and Ibn Ishaq."\ 17. Ibn Sa'd (d. 230/844-45). Ibn Sa'd was al-Waqidi's secretary, and relied considerably on his master's work for his own Kitab al Tabakat al Kabir, which is considered the first major biographical dictionary.\ 18. Al-Baladhuri (d. 279/892). He seems to have been a close friend of the caliphs Mutawwakkil and Musta'in. He studied in Damascus and Emesa, and in Iraq under Ibn Sa'd. Al-Baladhuri is now famous for his two historical works, Futuh al-Buldun and Ansab al-Ashraf. The former is a history of Muhammad beginning with his wars against the Jews, Mecca, Ta'if, and then the subsequent Arab conquests from the Maghrib to Persia. The latter begins with the sira of the Prophet, and continues with the history of the Abbasids, and so forth. He seems to have relied upon Ibn Ishaq and Ibn Sa'd, among others.\ 19. `Ali b. Muhammad al-Mada'ini (d. ca. 225/840). He was a very important source for the Arab conquests of Iran.\ 20. Al-Tabari (ca. 224 or 225/839-311/923). Born in Tabaristan, he traveled extensively in Egypt, visited Raiy, Basra, and Kufa, but eventually settled down in Baghdad. A considerable polymath, al-Tabari devoted much time to history, fiqh, the Koran, poetry, grammar, and even mathematics and medicine. His commentary on the Koran, Djami al Bayan fi Tafsir al Kuran, or simply Tafsir, has survived, and is of great importance since al-Tabari gathered together "ample material of traditional exegesis and thus created a standard work upon which later Kuranic commentators drew; it is still a mine of information for historical and critical research by western scholars." Even more important is al-Tabari's History of the World, Tarikh al-Rusul wa `l-Muluk, beginning with the prophets, patriarchs, and rulers of the early period, and ending precisely at 303 (July 915). Al-Tabari derived much of his material from oral traditions, but also literary sources like the works of Abu Mikhnaf, and of course the Sira of Ibn Ishaq, the writings of al-Waqidi, Ibn Sa'd, and so on.\ \ \ Characteristics of Sira Texts\ \ \ Although the above historians had differing approaches to the writing of the life of the Prophet and the rise of Islam, certain broad common themes seem to emerge. They all want to defend, embellish, and "build up the image of Muhammad in rivalry to the prophets of other communities, to depict him as a statesman of international stature, to elaborate on Kuranic texts and create a chronological framework for them, to record the deeds of the early Muslims, ... and to set standards for the new community."\ Most of them recount recount details of the raids, military expeditions, and eighty political assassinations carried out by the Prophet and his companions, with many romanticized deeds of heroism, single combats, and so on. Many give the genealogies (nasab, pl. ansab) of the various clans and individual Companions who took part in the events. It is also very clear as was probably first pointed out by C. H. Becker, and more recently John Wansbrough that large parts of the sira were inspired by the Koran; some texts merely paraphrase a Koranic passage. There are abundant examples of what are called the "occasions of revelation" (asbab al-nuzul), that is, accounts of the particular occasion when a certain passage was revealed. For example, when the Prophet was mocked the verse "Apostles have been mocked before you ..." (sura 6, verse 10) was revealed.\ C. H. Becker speaks of "exegetical elaborations of Koranic allusions," and he is probably referring to the many sira texts that expand on a Koranic passage rather like a Jewish midrash; for example, the episode of the "Satanic Verses" recounted in al-Tabari is an elaboration of sura 22, verse 52. There are quite long narratives in the sira that are rather flimsily built on various verses in the Koran.\ The sira tried to place the Prophet Muhammad among the prophets of old and to assert the identity of Islam among the other, older religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Manichaeism; in so doing, it extensively mined the already existing repertoire of symbols, myths, and structures and put them to use for the Muslims' own newly emerging system of belief. The twelve tribes of Israel and the twelve disciples of Jesus are paralleled, for example, by the twelve leaders appointed, at al-Aqaba, by Muhammad from the Ansar, the Helpers (that is, those citizens of Medina who rallied to Muhammad after his flight from Mecca). The sira also contains stories of miracles brought about by God through Muhammad, or by Muhammad himself as proofs of his prophethood. The sira incorporates speeches and sermons of the Prophet, but also "documents" such as treaties, letters putatively written by Muhammad to foreign rulers, and above all the so-called "Constitution of Medina," which is an agreement between Muhammad and the "believers and Muslims of Quraysh and Yathrib, and those who follow them, join them and strive alongside them" including Jewish groups.\ \ \ B. Manuscripts, Papyri\ \ \ 1. Khirbat al-Mird Papyrus, early second/eighth century. This papyrus contains just eight lines about the Battle of Badr, studied by Grohmann.\ 2. Chicago Papyrus (Oriental Institute, ms. no. 17635), late second/eighth century. This papyrus deals with Badr, Bi'r Ma'una, and the B. al-Nadir\ 3. The Berlin Manuscript, fourth/ninth century. Published by Sachau in 1904, this manuscript contains a short text of Musa b. Ukba (ca. 55/674-141/758).\ 4. The Heidelberg Manuscript, early third/ninth century, refers to the meeting at al-Akaba, the conference of Kuraysh, the Hijra, and the expedition against Khatham, which has an isnad, a chain of transmitters, going back to Wahb b. Munabbih.\ Thus only the Khirbat al-Mird papyrus of eight lines, dating from the early second/eighth century, is from the pre-Abbasid period. Otherwise we only have citations once-removed or more.\ (Continues...)

Preface9 Part One: Introduction 1 Studies on Muhammad and the Rise of Islam: A Critical Survey 15 Ibn Warraq 2. Origins of Islam: A Critical Look at the Sources 89 Ibn Rawandi Part Two: Renan 3. Muhammad and the Origins of Islam 127 Ernest Renan Part Three: Lammens and Becker 4 Koran and Tradition—How the Life of Muhammad Was Composed 169 Henri Lammens 5. The Age of Muhammad and the Chronology of the Sira 188 Henri Lammens 6. Fatima and the Daughters of Muhammad 218 Henri Lammens 7. Matters of Principle Concerning Lammens' Sira Studies 330 C. H Becker Part Four: Modern Period 8. The Quest of the Historical Muhammad 339 Arthur Jeffery 9. A Revaluation of IslamicTraditions 358 Joseph Schacht 10 Abraha and Muhammad: Some Observations Apropos of Chronology and Literary Topoi in the Early Arabic368 Lawrence I Conrad 11. The Function of asbab al-nuzul in Quranic Exegesis 392 Andrew Rippin 12. Methodological Approaches to Islamic Studies 420 J. Koren and Y. D Nevo 13. The Quest of the Historical Muhammad 444 F. E Peters 14. Recovering Lost Texts: Some Methodological Issues 476Lawrence I Conrad Part Five: The Significance of John Wansbrough 15 The Implications of, and Opposition to, the Methods of John Wansbrough 489 Herbert Berg 16. John Wansbrough, Islam, and Monotheism 510 G. R Hawting Glossary527 Abbreviations535 Dramatis Personae: Explanatory List of Individuals and Tribes537 Genealogical Table546 Map of Western Asia and Arabia547 Chronological Table and the Islamic Dynasties548 Contributors551

\ Publishers Weekly - Publisher's Weekly\ Warraq, author of Why I Am Not a Muslim, here offers a "quest for the historical Muhammad" using the same methodology established by scholars attempting to uncover the historical Jesus. Applying this approach to determine if early traditions about Muhammad and the birth of Islam are historically accurate, Warraq predictably finds that the faith tradition cannot support the historian's demanding gaze. For example, Warraq argues that the centrality of Muhammad himself (as the prophet of God, author of the Qu'ran and focal point of Islamic culture) did not emerge until at least two centuries after the death of the historical Muhammad. Warraq's subtext is significantly unlike the Jesus Seminar's similar work, in which historians who are also Christians struggle to sort out the ways that historical methodology may illuminate and enliven the faith tradition. As his earlier titles suggest, this is not the work of a Muslim in radical dialogue with his faith. Under the guise of scholarly objectivity, Warraq wages a vigorous attack on the traditions of Islam. Biases notwithstanding, there is also much useful scholarship here; not only has Warraq provided a highly readable critical survey of the literature of this quest, he has also collected the most important texts needed to begin a more objective evaluation of Islam's sacred tradition. The reader's task is to sort the polemic from the scholarship. (Mar.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\|\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis anthology of writings on Muhammad and early Islam "can be seen as an implicit criticism of this optimistic view of our historical evidence for the rise of early Islam." Rather than being a quest, as the title suggests, this work attempts to refute the traditional view and legitimacy of Islam and its founder. Contradictory statements concerning how much historical material is available on the life of Muhammad range from an overwhelming amount to practically none at all. The book, edited by Warraq (Why I Am Not a Muslim), readily admits to the anti-Islamic bias of some of its contributors. For example, Henri Lammens, who authored three chapters, is described as one who had "a holy contempt for Islam." Lammens himself refers to the Qur'an as an "infinitely shabby journal." Although very scholarly, this work is not balanced and is sure to cause a good deal of controversy in the Muslim world. Not recommended.--Michael W. Ellis, Ellenville P.L., NY Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\\ \ \ Internet BookwatchMore than a hundred years ago Western scholars began to investigate the origins of Islam, using historical scholarly standards to determine what could be known about Muhammad and early Islam. Warraq presents an important compilation of the best studies of Muhammad and early Islam, outlining the scholarly controversies which lie at the heart of Islam and considering the debates long suppressed throughout research history. An essential study evolves.\ \