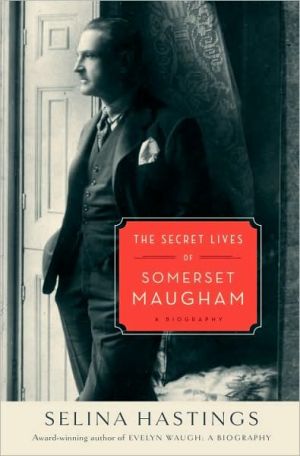

The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham: A Biography

An epic biography of a hugely talented and hugely conflicted man, now in paperback for the first time.\ He was a brilliant teller of tales, one of the most widely read authors of the twentieth century, and at one time the most famous writer in the world, yet W. Somerset Maugham’s own true story has never been fully told. At last, the truth is revealed in a landmark biography by the award-winning writer Selina Hastings. Granted unprecedented access to Maugham’s personal correspondence and to...

Search in google:

He was a brilliant teller of tales, one of the most widely read authors of the twentieth century, and at one time the most famous writer in the world, yet W. Somerset Maugham’s own true story has never been fully told. At last, the fascinating truth is revealed in a landmark biography by the award-winning writer Selina Hastings. Granted unprecedented access to Maugham’s personal correspondence and to newly uncovered interviews with his only child, Hastings portrays the secret loves, betrayals, integrity, and passion that inspired Maugham to create such classics as The Razor’s Edge and Of Human Bondage.Hastings vividly presents Maugham’s lonely childhood spent with unloving relatives after the death of his parents, a trauma that resulted in shyness, a stammer, and for the rest of his life an urgent need for physical tenderness. Here, too, are his adult triumphs on the stage and page, works that allowed him a glittering social life in which he befriended and sometimes fell out with such luminaries as Dorothy Parker, Charlie Chaplin, D. H. Lawrence, and Winston Churchill.The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham portrays in full for the first time Maugham’s disastrous marriage to Syrie Wellcome, a manipulative society woman of dubious morality who trapped Maugham with a pregnancy and an attempted suicide. Hastings also explores Maugham’s many affairs with men, including his great love, Gerald Haxton, an alcoholic charmer and a cad. Maugham’s courageous work in secret intelligence during two world wars is described in fascinating detail—experiences that provided the inspiration for the groundbreakingAshenden stories. From the West End to Broadway, from China to the South Pacific, Maugham’s restless and remarkably productive life is thrillingly recounted as Hastings uncovers the real stories behind such classics as “Rain,” The Painted Veil, Cakes & Ale, and other well-known tales.An epic biography of a hugely talented and hugely conflicted man, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham is the definitive account of Maugham’s extraordinary life. The Barnes & Noble Review Hastings brings an extraordinarily deft touch to the relationship between Maugham's life and his many plays, novels, and stories. She presents brisk summaries and just enough detail to place the works in the culture at large and, most nimbly, to illustrate what they drew from the circumstances of his own life. Maugham was a spy in Switzerland and Russia during the First World War, his experiences yielding Ashenden: or the British Agent (1928), which inaugurated the modern spy story (influencing Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John Le Carré), and which also became required reading for entrants into MI5 and MI6. In the next war, after a grueling escape from the Continent ahead of the Nazis, Maugham became a propagandist in the United States, eventually going to Hollywood for a brief, disheartening, most entertainingly described period. He was a world traveler for most of his life, excursions which Hastings presents in adroitly assembled detail. The foreign trips allowed him to spend time with Haxton, whose earlier misdeeds had gotten him banned from Britain; but mostly he was drawn to the strange and exotic and was fascinated by the bitter tensions in colonial communities, all fodder for his pen.

The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham\ A Biography \ \ By Selina Hastings \ Random House\ Copyright © 2010 Selina Hastings\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 9781400061419 \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ A Blackstable Boyhood\ \ For much of his long life—he lived to be over ninety—Somerset Maugham (1874–1965) was the most famous writer in the world. He was known everywhere for his superb short stories and for his novels, the immensely acclaimed, Of Human Bondage, becoming one of the most widely read works of fiction of the twentieth century. His books were translated into almost every known tongue, filmed, dramatized, and sold in their millions, bringing \ him celebrity and enormous wealth. Wherever he went he was pursued by journalists, eager for information: this extraordinary man seemed to know everyone, from Henry James to Winston Churchill, from Dorothy Parker to D. H. Lawrence. His magnificent villa in the south of France, much photographed and written about, was a byword for luxury and elegance. On the Riviera, as in London and New York, Maugham, always elegantly dressed, looked every inch the conventional English gentleman. And yet conventional he was not. In Maugham’s outwardly respectable life there was a great deal he was determined to keep hidden, and in old age, when he was besieged by would-be biographers, he did his utmost to make sure his privacy would remain intact. Evening after evening at the VillaMauresque, Maugham, assisted by his secretary, went systematically through his papers, throwing every last scrap of personal correspondence onto the fire. He also wrote to his friends asking them to destroy any letters of his in their possession; and he issued strict instructions to his literary executors that no biography should be authorized, no access to his papers be allowed, and all requests for information be firmly refused.\ \ And what were these areas of experience that it was so important to keep concealed? Mainly they were to do with his homosexuality, for Maugham lived in an era when in Britain homosexual practice was against the law. He was twenty-one at the time of the trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895, an event that traumatized a generation of men who were not by nature inclined toward marriage. And although Maugham himself did marry, and indeed fathered a child, his relations with his wife, Syrie, were wretchedly unhappy, even though he never allowed her for long to keep him apart from the great love of his life, a dissolute charmer named Gerald Haxton. Now, nearly half a century after Maugham’s death, the details of his long affair with Gerald and the harrowing story of his life with Syrie have come to light. The executors of the Maugham estate in London, the Royal Literary Fund, recently rescinded the clause in his will forbidding access to his correspondence; and a transcript has been uncovered of a long and detailed recording made by his daughter, Liza, of the inside story of her father’s private and domestic life. The material has turned out to be richly revealing: Liza, speaking to a close friend, was extremely frank; and ironically, Maugham’s request that his letters should be destroyed ensured not only that they were kept but that most were sold for very large sums to American universities.\ The story that unfolds is that of a man who after a harrowing and unhappy childhood learned early to live undercover; appropriately, in both world wars he worked for British intelligence, sometimes at considerable risk to his personal safety. He was further distanced by developing at an early age a stammer that made him agonizingly self-conscious; it inhibited him, and as an adult he formed the habit of having by his side an interpreter, a sociable, outgoing type, usually also his lover, who would make the initial contact and enable Maugham himself to keep more or less in the background. And yet for all his elaborate defenses Maugham remained intensely vulnerable; he was a passionate, difficult man, capable of cruelty as well as of great kindness and charm, but despite all his worldly success he never found what he wanted. His miserable marriage wrecked years of his existence, and the great love of his life remained unrequited.\ \ Many of his readers associate Somerset Maugham with the British Empire and the Far East, with Maugham himself a symbol of the quintessential English gentleman, the pukka sahib, descended from generations of old established county family. Yet in fact Maugham’s parents were recent arrivals among the professional middle classes, and they had lived not in England but in France: it was on French soil that Maugham’s life both began and ended. Maugham’s father, Robert Ormond Maugham (1823–1884), was a solicitor, the third generation to practice law in a family who were descended from farmers and small tradesmen in Westmoreland. It was Robert Maugham’s grandfather who had first come to London, where he had risen no higher than a lawyer’s clerk, although his son had gone on to achieve distinction not only in his legal practice but as one of the founders of the Law Society. Robert himself had done so well in the family business that in the 1840s he had moved to Paris to open a branch there, his partner, William Dixon, remaining behind to run the London office. The premises of Maugham et Dixon, juriconsultes anglais, were immediately opposite the British embassy, and here Maugham et Dixon prospered, especially after the firm’s semiofficial appointment as legal adviser to the embassy itself.\ \ By his mid-thirties Robert Maugham was making a good living, doing well from the boom years of Louis Napoleon and the Second Empire, when in Paris everyone seemed to be making money—“Enrichissez-vous!” was the cry. The population of the capital was enormously expanding, and so was the English community upon which much of the business of Maugham et Dixon naturally depended. Eventually Robert Maugham felt sufficiently well off to take a wife, and on the first of October 1863, at the age of thirty-nine, he married Edith Mary Snell, a ravishing young woman sixteen years his junior. Young Mrs. Maugham, daughter of an Indian army captain who had died when she was a baby, had lived in France most of her life. Her widowed mother had been socially superior to her husband, and it was one of her uncles who had been christened Somerset in honor of a distinguished godfather, the name to be passed on to his famous great-nephew, who never cared for it.\ \ After the wedding the Maughams settled into an apartment at 25 Avenue d’Antin (now Avenue Franklin D. Roosevelt), a broad street lined with chestnut trees just below the rond-point of the Champs-Élysées. Here for nearly seven years the couple enjoyed an agreeable existence, with Robert, “lively and gregarious,” working hard at his business while Edith ran the household and supervised the upbringing of the three boys who arrived in quick succession. Both Maughams were small in stature, but while Robert’s appearance verged on the brutish—he was plump, with a large sallow face, yellow whites to his eyes, and a bulbous chin framed by a mustache and bushy side whiskers—Edith was doll-like and beautiful. Her hair was a rich auburn, her pale complexion flawless, her dark brown eyes large and set wide apart. When Robert and Edith were seen together, the contrast was almost risible, and they became affectionately known as “Beauty and the Beast.” The Maughams enjoyed a lavish style of living, keeping a carriage, frequently attending the theater and opera, and entertaining generously. Edith dressed with style, the apartment was always filled with flowers, and the finest hothouse fruit, grapes and peaches out of season, appeared on the table. Much of the Maughams’ social life inevitably revolved around the embassy, but Edith also numbered among her friends writers and painters, among them Prosper Mérimée and Gustave Doré. Regarded as the reigning beauty of the English community, Mme Maugham was one of the few foreigners whose name was listed in the annual directory La Société et le High Life, and after her death she was described as an habituée of the most elegant salons, “une femme charmante, qui ne comptait que des amis dans la haute société parisienne, où elle occupait une des premières places.”* Such a eulogy almost certainly owes more to flattery than fact, but it is nonetheless clear that Edith Maugham was a woman of exceptional empathy and charm.\ \ In October 1865 the couple’s first child was born, a boy, Charles Ormond, followed a year later by Frederic Herbert, and in June 1868 by Henry Neville. The youngest had barely reached his second birthday when the Franco-Prussian War broke out, shortly followed by Napoleon III’s humiliating surrender in September 1870 at Sedan. With the Prussian army advancing on Paris, the Maughams, together with a large section of the English community, departed for England, leaving behind them at the Avenue d’Antin a couple of servants to look after the apartment and a Union Jack fastened to the balcony. During the terrible siege of Paris the starving populace was reduced to eating rats and animals from the zoo; as nothing could penetrate the German blockade, messages arrived from the Avenue d’Antin by carrier pigeon, one of them requesting to know whether Madame desired the summer covers to be put on the furniture in the drawing room. The five-month siege was succeeded by the bloody civil war known as the Commune, during which great swaths of the city were destroyed and more than twenty thousand people killed. But by the end of May 1871, government forces had regained control, and in August the Maughams returned to Paris, met at the Gare du Nord by their loyal manservant, François, who was able to tell them that the apartment had been left untouched by the Germans, thanks largely to their prominently displayed Union Jack.\ \ The apartment may have remained intact, but most of the center of the city presented a scene of desolation, the Tuileries a blackened ruin, the Hôtel de Ville a heap of rubble, the Colonne Vendôme toppled to the ground. Although rebuilding began at once and progressed with speed, it was some time before the business life of the city fully recovered, and with so many English having gone for good, Robert Maugham found himself perilously out of pocket, obliged to start almost from scratch in rebuilding his practice.\ \ In 1873 Edith again found herself pregnant. At that time the government, understandably anxious to strengthen its military might, was threatening the introduction of legislation imposing French nationality on all boys born in France to foreign parents, a measure that would automatically make them eligible for conscription. To circumvent this, the British ambassador, Lord Lyons, had authorized the rigging up of a maternity ward on the second floor of the embassy so that the wives of those immediately connected to the Chancery could safely give birth on British soil. And here on January 25, 1874, Edith’s fourth child was born, another boy, to be christened William Somerset.\ \ The years of Somerset Maugham’s early childhood were almost certainly the happiest of his life. By the time he was old enough to take notice, his three brothers, Charlie, Freddie, and Harry, had gone, sent off to school in England and coming home only for the holidays. The result was that little William led the life of a much-indulged only child, and with his father away at his office all day, returning only after the boy had been put to bed, he was in the happy position of having his adored mother entirely to himself. After the departure of his wet nurse, Willie was looked after by a French nursemaid, his “nounou,” with whom he shared a bedroom, and it was she who would take him in to see his mother in the morning while she was resting after her bath, a private interlude of perfect intimacy and love, the memory of which stayed with him always, to be poignantly recalled nearly forty years later:\ \ [The servant] took the child over to a bed in which a woman was lying. It was his mother. She stretched out her arms, and the child nestled by her sid . . . .?The woman kissed his eyes, and with thin, small hands felt the warm body through his white flannel nightgow . . . .\ \ “Are you sleepy, darling?” she said.\ \ . . . The child did not answer, but smiled comfortably. He was very happy in the large, warm bed, with those soft arms about him. He tried to make himself smaller still as he cuddled up against his mother, and he kissed her sleepily. In a moment he closed his eyes and was fast aslee . . . .?[T]he woman kissed him again; and she passed her hand down his body till she came to his feet; she held the right foot in her hand and felt the five small toes; and then slowly passed her hand over the left one.\ \ For Willie, his mother was the center of his entire existence. He loved her unreservedly and felt completely secure in her love for him. While his father remained a shadowy presence and barely impinged upon his consciousness, his mother’s attention, he knew, was always his, and nothing mattered to him much that did not concern the sweet intimacy that existed between himself and her.\ \ After visiting his mother, Willie was taken out, usually to play in the Champs-Élysées, in those days lined with private houses and luxurious apartment buildings. He and his nurse would make their way to the gardens at the end nearest the Place de la Concorde. Here there were always other children, and as he grew older Willie was allowed to play with them, dashing in and out of the shrubbery in vigorous games of La tour prend garde or Balle à l’ennemi. With his pale skin, fair curls, and large brown eyes, Willie in his black-belted suit was indistinguishable from the little French boys in their short trousers and lace-up boots who were his playmates; indeed he spoke French far more fluently than English, sometimes mixing the two. Edith was amused when one day her small son, catching sight of a horse from the window of a railway carriage, cried out, “Regardez, Maman, voilà un ’orse.” His first extant letter, written at the age of six and addressed to his parents, is in French: “cher papa, chere maman, votre petit willie est heureux au jour de noel de vous exprimer ses meilleurs souhaits, et sa reconaissante affection. croyez-moi, cher papa, chere maman, votre fils respectueux, willie maugham.”* In the afternoons, either his mother had nursery tea with him, or Willie went to the drawing room to be shown off to her guests. Occasionally he was asked to recite a fable of La Fontaine, after which, if he were lucky, some kind gentleman might tip him. On his seventh birthday one of his mother’s friends gave him a twenty-franc piece, which he chose to spend on his first visit to the theater; accompanied by his eldest brother Charlie, he saw Sarah Bernhardt in an “atrocious” melodrama by Sardou, which thrilled him to the core. \ \ Continues... \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham by Selina Hastings Copyright © 2010 by Selina Hastings. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Chapter 1 A Blackstable Boyhood 3\ Chapter 2 At St. Thomas's Hospital 31\ Chapter 3 A Writer by Instinct 58\ Chapter 4 Le Chat Blanc 77\ Chapter 5 England's Dramatist 108\ Chapter 6 Syrie 141\ Chapter 7 Code Name "Somerville" 178\ Chapter 8 Behind the Painted Veil 224\ Chapter 9 A World of Veranda and Prahu 253\ Chapter 10 Separation 290\ Chapter 11 The Villa Mauresque 318\ Chapter 12 Master Hacky 357\ Chapter 13 The Teller of Tales 394\ Chapter 14 An Exercise in Propaganda 436\ Chapter 15 The Bronzino Boy 484\ Chapter 16 Betrayal 518\ Acknowledgments 551\ Source Notes 555\ Select Bibliography 599\ Index 603\ Illustration Credits 625

\ Publishers WeeklyIn Hastings's new biography, the facts of Maugham's life form a fascinating narrative because they are full of public incident and accomplishment, shadowed by privately known and whispered secrets, Hastings is the first biographer with permission to quote from Maugham's private papers, and from observations by his daughter, Liza, concerning the disastrous court case instigated by his homosexual companion, Alan Searle, when Maugham (1874-1965), in his dotage, threatened to disinherit Liza. The sordid details, fully disclosed for the first time, reveal the tragic ending to a life that had produced great wealth, exotic travel, and public acclaim. Although Maugham maintained that he was “three quarters 'normal' and only a quarter 'queer,' '' Hastings demonstrates that Maugham's great love was his secretary and traveling companion, Gerald Haxton. She also documents the bitter relationship between a reluctantly married Maugham and his notorious wife, Syrie. In addition to his many homosexual love affairs, Hastings reveals Maugham's work as an espionage agent in two world wars. The biographer of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh, Hastings is a stylish and sensitive writer who addresses her subject's double life with insight and compassion. 32 pages of b&w photos. (June)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalHastings, the British biographer of Nancy Mitford, Evelyn Waugh, and Rosamond Lehmann, has produced a richly detailed and meticulously researched biography of Maugham (1874–1965), who was one of the most popular novelists and dramatists of the first half of the 20th-century. Employing many never-before-used archival materials, she covers all facets of the author's life and works. Maugham himself was opposed to a biography during his lifetime and destroyed many of the letters sent to him. His passionate but stormy relations with Gerald Haxton and Alan Searle, who were his secretaries and companions, are exhaustively examined along with his troubled marriage, friendships, rivalries (both literary and personal), and relations with other renowned authors and celebrities. While Hastings admits that Maugham was not a great writer, she sympathetically describes his major plays, stories, and novels, revealing his strengths as an observer of life in England and other countries and his unerring portraits of people and their individual stories. VERDICT Highly recommended for students of early 20th-century literature and readers interested in the private lives of famous writers. (Photographs and index not seen.)—Morris Hounion, NYC Coll. of Technology Lib., CUNY\ \ \ Michael DirdaAs this excellent biography by Selina Hastings makes clear, Somerset Maugham lived a life of quite astonishing richness and variety.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsMonumentally engaging account of W. Somerset Maugham's fiercely protected personal life (1874-1965). On the surface, Maugham's life was fulfilling and successful. His many plays, novels and stories earned him great fame and wealth, and his marriage to the socialite Syrie Wellcome provided him with a posh London home complete with lavish dinner parties with fashionable guests. Additionally, his handsome income allowed him the freedom to travel the world, including French Polynesia and the Far East, providing him with some of the most robust literary inspiration of his career. Maugham's emotional well-being, however, faced constant strife. From the death of his parents during childhood, Maugham was insecure and shy and suffered a debilitating stammer. He was also secretly homosexual. Literary biographer Hastings (Rosamond Lehmann, 2002, etc.), who had extensive access to Maugham's surviving letters and interviews with his only child, spares no detail in describing these other facets of the famous writer's existence. She writes with great perception about Syrie's duplicity and selfishness, the sham marriage providing Maugham with both the image of respectability (which "had always been of the utmost importance to him") but also much misery. It was his tumultuous relationship with the vivacious Gerald Haxton, with whom he shared his life for almost 30 years, that was Maugham's true passion-maintaining a pretense with Syrie was a tiresome, and expensive, chore. Haxton accompanied Maugham on his far-flung adventures, times that would remain some of the most cherished of his life. Hastings also recounts Maugham's two stints with British Intelligence, where he thrilled at secreting informationand disseminating propaganda, episodes that would inspire Maugham's much-admired Ashenden stories. All of the drama, intrigue, heartbreak and joy that marked Maugham's life is reconstructed by the author in enthralling, novelistic prose. A powerful, revealing and authoritative depiction of one the 20th century's most notorious literary figures. Agent: Melanie Jackson/Melanie Jackson Agency\ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewLike George Orwell, Henry James, and other untrusting souls, W. Somerset Maugham wanted no biography; but unlike them, he provided a lesson in the odium which an indiscreet account of a life can bring by composing his own. Written when he was 88, Maugham's memoir, Looking Back, was met by disgust and dismay at the venomous portrait the author drew of his deceased former wife. "Entirely contemptible" (Nöel Coward), "a senile scandalous work" (Graham Greene), "shabby, sordid, embarrassing" and "a wildly faggoty thing to have done" (Garson Kanin) were some of the responses.\ Maugham had been urged into this terrible misstep by his lover and general factotum, Alan Searle, who had been promised the proceeds from its publication, and by press baron Max Beaverbrook, who had newspaper sales on his mind. It was a miserable way to cap off a writing life which had made Maugham one of the most famous authors in the world and certainly the richest. That memoir, along with Maugham's acrimonious, well-publicized break with his daughter and her family, his notorious thralldom to Searle, and the ever-continuing speculation about what wicked things went on at his villa on the French Riviera, have left a miasma around Maugham's whole life. That he made bonfires of his papers and directed his correspondents to burn all his letters has not only thickened the air of unseemliness, but has also made writing a substantive biography difficult. Attempts have been made; but none so far has the scope and grace of Selina Hastings's. Though she is the first biographer to be granted access to Maugham's remaining papers, it is really her own command of the territory, empathetic judgment, and dexterous use of sources that make this book the brilliant work that it is.\ William Somerset Maugham, much the youngest of four surviving brothers, was born in 1874 in a rigged-up maternity ward in the British embassy in Paris, a little bit of England arranged for British subjects to evade having their newborns registered as French citizens. The first and all-encompassing tragedy of Maugham's life was the death of his mother when he was eight, the trauma leaving him with a life-long stammer. A couple of years later, his father died and young Maugham was sent by himself to live with his married uncle, a clergyman, the model for the Vicar of Blackstable in the novel, Of Human Bondage (1915). ("He was not a cruel man, but a stupid, hard man eaten up with a small sensuality.")\ Thus began the "period of utter desolation" that was the rest of Maugham's childhood. At sixteen, he went to Heidelberg to learn German and, as it happens, to lose his virginity to a fellow Englishman. Returning to England a year later, he spent five years studying and practicing medicine at St Thomas's, a charitable hospital in Lambeth. It was there, he said, that he learned everything he knew about human nature. The immediate result was his first novel, Liza of Lambeth, published in 1897, which launched his literary career -- an impoverished one until he turned to the theatre in 1907.\ His first play, Lady Frederick, a comedy of manners, was an immediate success, as were most of the plays that followed in the next two decades -- a success, that is, at the box office and in the eyes of the general public. The mandarin view, expressed by the critic Desmond McCarthy, was more dyspeptic: "They were just cynical enough to make the sentimental-worldly think themselves tough-minded while they were enjoying them, and just brilliant enough to satisfy a London audience's far from exacting standard of wit." This pretty much sums up the high-literary disdain for Maugham's work, books included, that endures today. It galled the author for the rest of his life: "The intelligentsia," he wrote, "flung me, like Lucifer, headlong into the bottomless pit. I was taken aback and a little mortified." Be that as it may, Maugham's success as a playwright freed him from what had begun to seem the fiction writer's drudgery: "Thank God," he later recalled saying to himself, "I can look at a sunset now without having to think how to describe it." In fact, however, he did continue to write novels, short stories, and travel pieces -- and, by the early 1930s, decided he loathed the theatre.\ If the defining heartbreak in Maugham's life was the death of his mother, its turmoil was, in one way or another, the result of his sexual orientation. The trial, imprisonment, and ruination of Oscar Wilde in 1895 haunted him, lending urgency and a certain pathos to his insistence that he was three-quarters "normal" and only one-quarter "queer." Maugham was convinced that to gain "peace and a settled and dignified way of life," he should get married. Hastings conveys how truly and chillingly he believed this, to the extent, indeed, that even after his own harrowing experience with the married state, he still recommended it to his nephew Robin, also gay.\ The first woman Maugham sought in marriage turned him down; the second relentlessly maneuvered him into it. This was Syrie Wellcome, separated wife of the pharmaceutical manufacturer Henry Wellcome, daughter of the social-reformer, Thomas Barnardo, mistress of Gordon Selfridge, the department store tycoon, and, in time, the model for Evelyn Waugh's hardnosed operator, Mrs. Beaver, in A Handful of Dust.\ To make a long, unedifying story short, the marriage was a disaster: the couple had nothing in common in taste or expectation. Moreover, as Hastings observes, Syrie "made the fatal mistake of falling in love with her husband." Her neediness and jealousy were aggravated by Maugham's having already found the love of his life in the American charmer, Gerald Haxton: an outgoing hedonist, "a bit of a chancer," and a bona fide sex pot. But the marriage was also doomed by Syrie's "moral crassness," best represented in her turning the Maugham establishment into a interior-decorator's salesroom. The last straw came when she sold her husband's long-cherished writing table right out from under him.\ Hastings brings an extraordinarily deft touch to the relationship between Maugham's life and his many plays, novels, and stories. She presents brisk summaries and just enough detail to place the works in the culture at large and, most nimbly, to illustrate what they drew from the circumstances of his own life. Maugham was a spy in Switzerland and Russia during the First World War, his experiences yielding Ashenden: or the British Agent (1928), which inaugurated the modern spy story (influencing Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John Le Carré), and which also became required reading for entrants into MI5 and MI6. In the next war, after a grueling escape from the Continent ahead of the Nazis, Maugham became a propagandist in the United States, eventually going to Hollywood for a brief, disheartening, most entertainingly described period. He was a world traveler for most of his life, excursions which Hastings presents in adroitly assembled detail. The foreign trips allowed him to spend time with Haxton, whose earlier misdeeds had gotten him banned from Britain; but mostly he was drawn to the strange and exotic and was fascinated by the bitter tensions in colonial communities, all fodder for his pen.\ His fiction reflected his appetite for news of other people's lives, an appetite shared by his increasingly large audience of readers. On the other hand, those unfortunates whose own characters and circumstances had provided his subject matter felt violated. This was especially true of people he had heard of, met, or even been the guest of in those moribund colonial outposts, men and women who discovered their stories or something very like them in The Trembling of a Leaf (1921), On a Chinese Screen (1922), and The Painted Veil (1925). To be sure, London's literary world provided rich fodder as well. Hugh Walpole, scarcely disguised as Alroy Kear in Cakes and Ale (1930) (which also features a Thomas Hardy-based character) was almost driven mad by the unflattering portrayal. It is hard not to think that Maugham's popularity relied on his punishing eye as much as his storytelling might, considerable though that certainly is.\ Maugham's thirty-year affair with Haxton ended unhappily, the younger man having become an impossible drunk, to some extent because he had nothing to show for his life except his relationship with Maugham. His death plunged Maugham into a frenzy of grief and self-castigation. In Alan Searle, his final lover, Maugham sought "the ideal companion," but instead found a man whose sweetness was offset by "something unctuous and money-grubbing in his demeanor." Developing into a "podgy Iago," Searle bore an animus against Maugham's daughter and connived at the old man's paranoia and isolation. In 1965, Maugham finally died, demented and terrified, in the Villa Mauresque in Cap Ferrat, once the scene of untold, perhaps unspeakable, revelry.\ Hastings is masterful throughout in creating a sense of place and personality, melding sources with an alchemist's hand to create a lively, seamless narrative rich in apposite quotation. She has also furnished the book with excellent, telling photographs of most of the major players. It is impossible to think that this biography will ever be surpassed.\ --Katherine A. Powers\ \ \