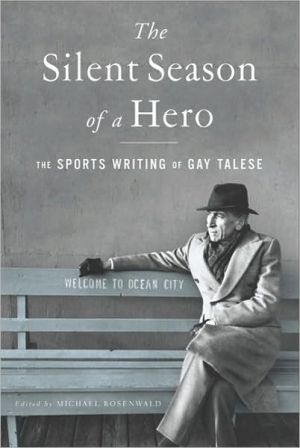

The Silent Season of a Hero: The Sports Writing of Gay Talese

One of America's most acclaimed writers and journalists, Gay Talese has been fascinated by athletes throughout his life. At age fifteen he became a sports reporter for the weekly Ocean City Sentinel-Ledger; four years later, as sports editor of the University of Alabama's Crimson-White, he began to employ techniques, such as establishing a "scene" with minute details, that would later make him famous.\ As a sports reporter for the New York Times, Talese was drawn to individuals at poignant...

Search in google:

One of America's most acclaimed writers and journalists, Gay Talese has been fascinated by sports throughout his life. At age fifteen he became a sports reporter for his Ocean City High School newspaper; four years later, as sports editor of the University of Alabama's Crimson-White, he began to employ devices more common in fiction, such as establishing a "scene" with minute details—a technique that would later make him famous.Later, as a sports reporter for the New York Times, Talese was drawn to individuals at poignant and vulnerable moments rather than to the spectacle of sports. Boxing held special appeal, and his Esquire pieces on Joe Louis and Floyd Patterson in decline won praise, as would his later essay "Ali in Havana," chronicling Muhammad Ali's visit to Fidel Castro. His profile of Joe DiMaggio, "The Silent Season of a Hero," perfectly captured the great player in his remote retirement, and displayed Talese's journalistic brilliance, for it grew out of his on-the-ground observation of the Yankee Clipper rather than from any interview. More recently, Talese traveled to China to track down and chronicle the female soccer player who missed a penalty kick that would have won China the World Cup.Chronicling Talese's writing over more than six decades, from high school and college columns to his signature adult journalism— and including several never-before-published pieces (such as one on sports anthropology), a new introduction by the author, and notes on the background of each piece—The Silent Season of a Hero is a unique and indispensable collection for sports fans and those who enjoy the heights of journalism. The New York Times - Gordon Marino …Talese does not so much convince you that he got a person right—whatever that would mean—as make you feel as if you were actually hanging out with him as he practices what he has always humbly termed "the art of hanging out. Though the athletes he first shadowed and then captured predated even ESPN by a generation or two, Talese's work remains riveting…As this marvel of an anthology makes manifest, Talese transformed sportswriting into literature that is both serious and delightful.

THE SILENT SEASON OF A HERO\ The Sports Writing of Gay Talese \ \ Walker & Company\ Copyright © 2010 Gay Talese\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-8027-7753-9 \ \ \ Introduction\ Gay Talese \ The jockey came to the doorway of the dining room, then after a moment stepped to one side and stood motionless, with his back to the wall. The room was crowded, as this was the third day of the season and all the hotels in the town were full ... He examined the room until at last his eyes reached a table in a corner diagonally across from him, at which three men were sitting ... a trainer, a bookie, and a rich man. The trainer was Sylvester—a large, loosely built fellow with a flushed nose and slow blue eyes. It was Sylvester who first saw the jockey ... Sylvester turned to the rich man. "If he eats a lamb chop, you can see the shape of it in his stomach a hour afterward. He can't sweat things out of him any more ..." —Extracted from "The Jockey," a short story first published in the New Yorker on August 23, 1941 and written by Carson McCullers when she was twenty-four years old.\ When I was twenty-four years old in 1956, and was working as a feature writer in the sports department of the New York Times, I read "The Jockey" for the first time in a paperback anthology, and as I read and reread that memorable sentence—"If he eats a lamb chop, you can see the shape of it in his stomach afterward"—I kept wondering how Carson McCullers had come to write it. Had she once met an aging and food-craving jockey whose taut and tiny stomach was imprinted with the shape of a lamb chop? Did she just dream up the image? Did some horse trainer or jockey describe it to her? From reading articles about her in the press—she was quite famous as a young woman, having published at twenty-three a best-selling first novel, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter—I knew that when she was twenty-four she was living near a race track in upstate New York while enrolled as a writer-in-residence at the Yaddo artists' retreat; and I assumed that during this time she had mingled with the racing crowd and had gathered the material out of which would come "The Jockey"—although nothing that I had read about her confirmed this. All I knew was that Carson McCullers suffered a stroke before her story appeared in the New Yorker, and that within a few years she experienced two more strokes that partly paralyzed her and caused her to write thereafter, until a final stroke finished her at fifty, with one finger on a typewriter—leaving behind a body of work that included five novels, two plays, twenty stories, and that single line about the lamb chop that to me represented a peculiarly interesting and original way of creating in a few words a lasting impression.\ As a young writer I never aspired to follow Ms. McCullers into fiction, even though she and most of the other writers that appealed to me used their imaginations to tell their stories. They fabricated reality. They made up names and provided their characters with words, scenes, and situations. They fantasized, mythologized, and created mysteries and sometimes magic with their prose. When I was in college studying journalism I spent my leisure time reading novels and short stories while wondering how I might best borrow the tools of a fiction writer—scene-setting, dialogue, drama, conflict—and apply these to the nonfiction pieces I hoped to contribute someday to a major newspaper or magazine. There were so many fine fiction writers, it seemed to me, and not enough nonfiction writers who had mastered the art of storytelling, and so it was my goal to become one of these.\ But I wanted to write short stories using real names, to describe situations that had truly occurred and were factually verifiable. I wanted to be there in person, to observe situations with my own eyes, and to describe what I saw in a literary manner worthy of those writers I admired and whose special sentences and word choices I often underlined on the page, sometimes adding in the margin a complimentary comment or perhaps a question of my own about the usage.\ After first reading "The Jockey," I underlined Carson McCullers's description of the horse trainer Sylvester—"a large, loosely built fellow with a flushed nose and slow blue eyes." Slow blue eyes? I wondered: What does she mean by slow? Maybe a typo for "sloe-eyed," I thought. But no, I decided after consulting a dictionary, she must be referring to the fifth definition listed there: "slow—sluggish, inactive ..." Yes. Later she described how the jockey entered the race track's restaurant and "scrutinized the room with pinched, crepe eyes ..." To the dictionary again: "crepe—a light, soft thin fabric of silk, or another fiber, with a crinkled surface." Ah, pinched, crêpe eyes—yes. And that lamb chop: At first I doubted the possibility of anyone being able to see its shape on the jockey's stomach, and so one day in 1958 when I was given an assignment by the sports editor to interview an ex-jockey named Harry Roble—who had once been the top jockey in the United States—I decided to question him about the lamb chop. I began by describing Ms. McCullers's story to him (he had never heard of it); but after I read him the line I loved, he nodded and said, "Yes, that's possible," adding, "I never liked lamb chops, but I'd sometimes sneak in a steak afterwards I could feel the damn steak pressed against my skin. In those days, when I was weighing 98 pounds and struggling to keep it at that, I'd even put on two pounds with each bowl of soup."\ In my profile on the ex-jockey, which appeared in the Times's sports page on July 20th of 1958, I wrote this lead (privately dedicating it to Carson McCullers):\ Harry Roble was one of those jockeys who gained two pounds after every bowl of soup and, if he ate a steak, you could sometimes see its lumpy outline lodged in his stomach.\ Among other fiction writers who influenced me during those days were Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John O'Hara, and Irwin Shaw, the latter two being regular contributors to the New Yorker, which I began reading shortly after I was hired as a copyboy on the Times in the summer of 1953 following my graduation in June from the University of Alabama. At Alabama I'd been the sports editor of the campus newspaper, the Crimson-White, and I also wrote a column called "Sports Gayzing" that at times tried to emulate such well-known columnists as Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, and Dan Parker. At the same time I was drawn more to the authors of fictional stories in magazines, especially when their stories were set within the atmosphere of sporting events: Hemingway on bull fighting and fishing, O'Hara on the esoteric game of court tennis, Irwin Shaw on football, and F. Scott Fitzgerald on a status-conscious caddy who carried bags at a club in Minnesota, where Fitzgerald grew up.\ Fitzgerald's story "Winter Dreams" was my all-time favorite. In the opening section it described the caddy skiing over the snow-covered hills of the country club feeling offended that "the links should lie in enforced fallowness," but then in April the members reappeared to play golf with red and black balls that were easier to see than white ones when hit into patches of snow along the fairways and the rough—and among the sharp-eyed caddies who most quickly spotted the balls was Fitzgerald's young hero Dexter Green.\ As a schoolboy I also worked at times as a caddy, doing so at a club across the bay from my hometown in Ocean City, N.J.; and like Dexter Green, I always closely followed the direction of the ball after the golfer had hit it, and rarely did I fail to find it no matter where it had landed. Indeed, my capacity to retrieve golf balls would help me decades later while researching a piece for Esquire on Joe DiMaggio, which would be published in July of 1956, fifteen years after he had retired from baseball.\ I had first been introduced to DiMaggio in 1965 at an "Old Timers" game at Yankee Stadium by a New York Times photographer we both knew; and during our friendly chat in the locker room DiMaggio indicated that he would be willing to see me whenever I happened to be in his hometown of San Francisco. Months later I notified him in a letter that I was coming, but on entering the restaurant he owned on Fisherman's Wharf I was rebuffed in a way that astonished me but that also provided me with my article's opening scene, one in which I was ejected from the premises by Joe DiMaggio himself. The fact that I was able to become reacquainted with DiMaggio a few days later was the result of a request that I had made through one of DiMaggio's friends and golfing partners that I be allowed to follow their foursome through one eighteen-hole round at a club in the outskirts of San Francisco. During the golfing session, DiMaggio, who hated to lose golf balls, lost three of them. I found them. After that DiMaggio's attitude toward me improved noticeably. I was invited to other matches and to join him in the evening at social events as well as to interview him in his home, and finally to accompany him on a flight to the Yankees' spring training camp in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he served as a batting instructor.\ Having been forewarned by one of DiMaggio's friends, I never questioned him directly about his private life with the late Marilyn Monroe, whose break-up of their marriage was said to have caused him much grief and frustration. But my approach to the piece was never intended to deal with the reality of the DiMaggio-Monroe relationship but rather with DiMaggio's sense of loneliness and longing for a woman he had idealized and had lost, and who, following her death, had left him with little else but to mourn her. As I mentioned in the piece, he ordered that fresh flowers be placed on her grave "forever."\ What I wrote about DiMaggio was laden with nostalgia, which is true as well of Fitzgerald's story about Dexter Green—who, after his caddying days were over and he had fulfilled his ambition to become very rich, was playing golf one day with other affluent men when he saw, pitching a ball into a sand pit on the other side of the green, a young woman whom he had first seen a decade or so earlier when she had been taking lessons as an eleven-year-old and he was a caddy of fourteen. Her name was Judy Jones, and now in the story Dexter Green pauses to appreciate the reappearance of her in his life:\ She wore a blue gingham dress, rimmed at the throat and shoulders with a white edging that accentuated her tan. The quality of exaggeration, of thinness, which had made her passionate eyes and down-turned mouth absurd at eleven, was gone now. She was arrestingly beautiful.\ Of course Dexter Green fell in love with her, and while this would in time proceed to an exciting affair it was one that she impulsively terminated as her attentions were drawn to another man, and then another. Dexter Green soon moved from the Midwest to Wall Street and added to his fortune, but he was finally forced to conclude, as Fitzgerald had phrased it, that Judy Jones:\ ... was not a girl who could be "won" in the kinetic sense ... She was entertained only by the gratification of her desires and by the direct exercise of her own charm. Perhaps from so much youthful love, so many youthful lovers, she had come, in self-defense, to nourish herself wholly from within.\ I thought that this could have been written about Marilyn Monroe; and, in fact, as Fitzgerald's biographers have pointed out, the fictional Judy Jones was based on a real woman whom Fitzgerald himself had once ardently courted—a lovely and elusive Midwestern socialite named Ginevra King. It is also true, I believe, that there was a bit of Dexter Green's spirit in Joe DiMaggio and me and in many of the men I have encountered and befriended since I first came to New York in 1953 as a copyboy. I then learned a month later, much to my despair and in spite of my best efforts to get her to change her mind, that the first love of my life—my Judy Jones in Alabama—had left me for someone else. Although a half-century has since passed and I have never seen her again, I have—like Dexter Green in "Winter Dreams"—regularly kept up with her through the comments and observations of mutual friends who occasionally visit me in New York. Whenever she is mentioned, I cease thinking about other things and listen. And after I had been promoted from copyboy to reporter and had published a piece about caddies in the June 12, 1960 issue of the New York Times Magazine, my lead began with Fitzgerald's description of what a wealthy Dexter Green was thinking as he and his golfing partners advances along the fairway:\ ... he found himself glancing at the four caddies who trailed them, trying to catch a glance or gesture that could remind him of himself, that would lessen the gap which lay between his present and his past ...\ Another fiction writer who influenced my early journalism was Irwin Shaw, who, before he began publishing such best selling novels as The Young Lions, Rich Man, Poor Man, and The Troubled Air, and also more than eighty stories in various magazines, had been a football player at Brooklyn College. He brought his knowledge of the game to much of what he had created with his prose. He once told a class he was teaching: "Writing is an intellectual contact sport, similar in some respects to football. The effort required can be exhausting, the goal unreached, and you are hurt on almost every play; but that doesn't deprive a man or a boy from getting peculiar pleasures form the game."\ From reading his fiction I saw greater possibilities from myself as a writer of nonfiction, as a scene-setter, a dialogue writer, a reporter who could recount true-to-life tales more fully and interestingly by deviating from the then prevailing formulaic code of 5-W journalism (who-what-when-where-why) and employing the story-telling techniques of people like Irwin Shaw. While my efforts were often rejected or rewritten by my editors (after I had reviewed packages of my old clippings in the Times's morgue in 1959 and had underlined certain words and sentences and had scribbled next to them my complaint: "I didn't write this!," the morgue's director inserted a note of his own: "GT: Modesty will get you no where. Mutillating morgue clippings is worse than a Federal offense!") I did manage, through some polite persuading on my part and the good will of my superiors, to get into the paper word-for-word much of what I wrote.\ For example in 1958 when I was sent to cover the spring training activities of the San Francisco Giants baseball team I devoted an entire piece to the wearability of the players' uniforms, pointing out that after one season the uniforms become "too weary for major league play and are sent down to the minors." In the same year I wrote a nineteen-paragraph profile about a young prize fighter named Jose Torres without mentioning his name until the last paragraph. Similarly in 1958 I covered a college baseball game between New York University and Wagner College that was held in freezing early-spring weather in front of only eighteen spectators. I described the game through the perspective of the spectators, focusing my attentions, for example, on a nineteen-year-old hazel-eyed brunette sophomore named Gloria Maurikis who had shivered through the game out of affection from the N.Y.U. third baseman, Dick Reilly, whom she had met five months before in Sociology I, a required course. The N.Y.U. team was leading 3–0 going into the seventh inning, and as I wrote in the last paragraph: "The score remained unchanged until Reilly's double in the seventh scored two more and sent Gloria home."\ Writing about a young woman sitting in the bleachers watching a sporting event was perhaps an idea I'd appropriated, without consciously realizing it, through my familiarity with many of Irwin Shaw's romantic scenes involving athletes. There are many such scenes in his story "The Eighty-Yard Run." The two main characters are named Christian Darling, a handsome substitute halfback on a college team in the Midwest, and his wealthy girlfriend Louise, who is described in the story as the lovely daughter of an ink manufacturer. On the sunny afternoon after Christian Darling had run for eighty yards in a practice session, Louise is waiting for him outside the stadium in her car with the top down; and, as he approaches, she opens the door and asks:\ "Were you good today?" "Pretty good," he said. He climbed in, sank luxuriously into the soft leather, stretched his legs far out. He smiled, thinking of the eighty yards. "Pretty damn good."\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from THE SILENT SEASON OF A HERO Copyright © 2010 by Gay Talese. Excerpted by permission of Walker & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Introduction Gay Talese 1Sports Gay-zing 17Short Shots in Sundry Sections 21Talking Basketball with Angelo Musi 25The Locker Room 29An Afternoon on the Football Field 33The .200 Hitter 37The Loneliest Guy in Boxing 41N.Y.U. Wins Despite 2-Way Freeze 49Judy Is Many Things, Mostly Frank 51It's a Wonderful Whirl to Gerry 55Portrait of a Young Prize Fighter 57Garden Horseshoer Works Fast 60Last of Bare-Knuckle Fighters Still Spry at 93 62Troupe of Midget Wrestlers Won't Work for Small Change 65Barbell King: Muscle Over Mind 68Dentist Puts the Bite in the Fight 70Timekeeper as Quiet as a Clock 73Diamonds Are a Boy's Best Friend 75On the Road, Going Nowhere, With the Yankees 83Notes from the Trip 88The Story Behind the Signal To Brush Back Cliff Johnson 95Race, Reporters and Responsibility 104The Fighter's Son 108The Loser 111Portrait of the Ascetic Champ 113Patterson, Indifferent at first, Finally Turns on Barking Dog 123Liston Aides Extol His Gaiety, Benevolence and Ruggedness 127Patterson Has 4 Friends, Too, But He'll Have to Fight Alone 129Champion Talks About Sleep and Rain and Watches His Entourage Close Camp 132Floyd Caught by 'a Good Punch' 135Masked Ex-Champion 137The Loser 141Stories With Real Names 167The Caddie-A Non-Alger Story 169Suspicious Man In the Champ's Corner 175Dr. Birdwhistell and the Athletes 186Joe Louis: The King as a Middle-Aged Man 201Silent Season of a Hero 218Architect of the Fairways 246Eric and Beth Heiden: A Bond of Blood on Skates 255The Kick She Missed 261The Greatest 273Ali in Havana 275Overtime 303Swan Song for Gay Talese 305

\ Publishers WeeklyTalese has covered a number of topics, but his career's most constant thread is sports, and this collection show what makes his writing so strong: Talese finds the poignant in the everyday. In "Portrait of a Young Prize Fighter," for instance, Talese withholds his subject's name until the end: "This young prize fighter's name happens to be Jose Torres. But he actually thinks, talks and dreams like dozens of other inexperienced professionals who train each day in Stillman's... seem to agree that despite all the punching, boxing still beats working for a living." It's a deft way to show the near-impossibility of becoming a household name in a crowded field. Even a simple piece about college ball has the kind of descriptive prose hardly seen in this genre today. Whether recounting a workaday game or taking on the monolithic topic of Muhammad Ali--which he did so well in his 1996 Esquire piece, "Ali in Havana," (included here)--Talese's writing possesses so much color and clear description of the world beyond the stadium that even non-sports fans will cheer. Photos. (Oct.)\ \ \ \ \ Gordon Marino…Talese does not so much convince you that he got a person right—whatever that would mean—as make you feel as if you were actually hanging out with him as he practices what he has always humbly termed "the art of hanging out. Though the athletes he first shadowed and then captured predated even ESPN by a generation or two, Talese's work remains riveting…As this marvel of an anthology makes manifest, Talese transformed sportswriting into literature that is both serious and delightful.\ —The New York Times\ \