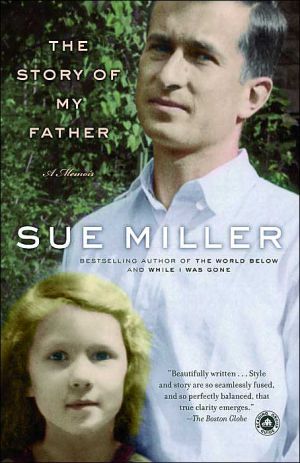

The Story of My Father: A Memoir

A NEW YORK TIMES NOTABLE BOOK \ In the fall of 1988, Sue Miller found herself caring for her father, James Nichols, once a truly vital man, as he succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease. Beginning an intensely personal journey, she recalls the bitter irony of watching this church historian wrestle with his increasingly befuddled notion of time and meaning. She details the struggles with doctors, her own choices, and the attempt to find a caring response to a disease whose special cruelty is to...

Search in google:

A NEW YORK TIMES NOTABLE BOOK In the fall of 1988, Sue Miller found herself caring for her father, James Nichols, once a truly vital man, as he succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease. Beginning an intensely personal journey, she recalls the bitter irony of watching this church historian wrestle with his increasingly befuddled notion of time and meaning. She details the struggles with doctors, her own choices, and the attempt to find a caring response to a disease whose special cruelty is to diminish the humanity of those it strikes. In luminous prose, Sue Miller has fashioned a compassionate inventory of two lives, a memoir destined to offer comfort to all sons and daughters struggling to make peace with their fathers and with themselves. The New York Times Novelists, Flaubert said, disappear behind their work. It's safe to say that memoirists do not. The Story of My Father is actually more the story of Sue Miller. Is this why memoirs are so tempting to writers? Because they give us permission to be self-serving? I ask this as someone not immune to the disease: I've written one myself. To put the best face on it, memoirs are testimonials to the private life. But they may owe their popularity to contrary forces — to our contempt for the private and the personal, both of which we seem bent on defiling. We display our secrets on the Web or reveal them to Oprah, anything to dissolve them in the acid bath of public exposure. In this respect, Miller's book should be admired for its struggle between tell-all, all-the-time revelation and the virtues of privacy and reserve. And we may hope that what she hasn't told us here is being saved for a novel. — John Vernon

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ When a novelist is as deft as Sue Miller at underlining the great drama and humanity in the small gestures and circumstances of everyday life, analytical types might surmise that her approach serves as a filter for interpreting her world. Her bestselling The Good Mother can be read as an encapsulation of her feelings about the conflicts of romantic entanglements with child rearing; The Distinguished Guest was a roman à clef about dealing with her charismatic, difficult mother. So her decision to write about her father and his Alzheimer's-induced decline in the form of a memoir indicates the depth of her emotions on this extremely personal matter. In the years before his eventual death, Miller's father, a retired minister, became increasingly unfamiliar to -- and dependant on -- the offspring who had grown up in awe of him. Using this steady decline as a frame for her larger narrative (her father's condition progressed from intermittent forgetfulness, confusion, and strangely charming hallucinations to frightening and violent outbursts), Miller writes touchingly of her father's life, of her place in it, and of his place in hers. At the same time, she discourses about her work, and about the writer's mining her own life experiences for art. In the end, Miller leaves us with a rare result: a book that offers instruction, information, and sympathy for the adult children of Alzheimer's sufferers and real, intuitive expression about the writer's role in experiencing and recording it. Katherine Hottinger\ \ \ \ \ The New York TimesNovelists, Flaubert said, disappear behind their work. It's safe to say that memoirists do not. The Story of My Father is actually more the story of Sue Miller. Is this why memoirs are so tempting to writers? Because they give us permission to be self-serving? I ask this as someone not immune to the disease: I've written one myself. To put the best face on it, memoirs are testimonials to the private life. But they may owe their popularity to contrary forces — to our contempt for the private and the personal, both of which we seem bent on defiling. We display our secrets on the Web or reveal them to Oprah, anything to dissolve them in the acid bath of public exposure. In this respect, Miller's book should be admired for its struggle between tell-all, all-the-time revelation and the virtues of privacy and reserve. And we may hope that what she hasn't told us here is being saved for a novel. — John Vernon\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyMiller's first nonfiction book (after While I Was Gone; The World Below; etc.), about caring for her Alzheimer's-afflicted father, is a rare example of an illness memoir with widespread appeal. Prospective readers need not have any interest in Alzheimer's; they need only have parents of their own to appreciate this testimony's dignity and grace. Miller's father, James Nichols, started showing signs of dementia in 1986, when he was picked up by the police after ringing a stranger's doorbell in the middle of the night, announcing he was lost. Miller's careful recounting of James's slow demise and progression through the various stages of an assisted living community are punctuated by pleasant memories and even humor, e.g., when James, a retired religious scholar, assesses his surroundings and comments, "No one ever seems to graduate from here." As she recalls childhood stories and family memories, Miller simultaneously offers a memoir of her own development as a writer. "[T]his is the hardest lesson... for a caregiver: you can never do enough to make a difference in the course of the disease," Miller writes. "We always find ourselves deficient in devotion.... Did you visit once a week? you might have visited twice. Oh, you visited daily? but perhaps he would have done better if you'd kept him at home. In the end all those judgments, those self-judgments, are pointless. This disease is inexorable, cruel. It scoffs at everything." 11 photos. BOMC alternate. (Mar. 19) Forecast: Miller's popularity among women readers of literary works-many whom are probably dealing with aging parents themselves-could shoot this one onto bestseller lists, and Knopf shouldn't have trouble selling out its 75,000 first printing. Copyright 2003 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis first nonfiction work from novelist Miller (The World Below) is a thoughtful remembrance of her relationship with her father, especially during his later years, when his memory loss caused by Alzheimer's became apparent. It is also a meditation on the meaning of writing in her life. A clergyman and church historian, James Nichols was an occasionally absent but always attentive father during Miller's childhood. Although father and daughter grew apart as she struggled to launch her writing career, their bond rekindled as Nichols's memory impairment became evident and his independence declined. After his diagnosis, she helped him restore an old house and found him assisted living and then nursing home care as he gradually disappeared into a world of hallucinations and delusions that turned increasingly violent. Near the end of his life, Miller realized that "my father's illness would be progressive, no matter what I did. You can never make a difference in the course of the disease." After ten years, many false starts, and two more novels, she finally completed this memoir. While writing enabled her to "snatch him back from the meaninglessness of Alzheimer's," it also deepened her understanding of what her father's disease and death meant to him. More reflective than Eleanor Cooney's Death in Slow Motion, this includes little of the medical information found in Charles P. Pierce's Hard To Forget: An Alzheimer's Story. Miller's very personal account is a marvelous addition to the growing literature of Alzheimer's memoirs and will appeal to fans of her novels as well. [Previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 10/1/02.]-Karen McNally Bensing, Benjamin Rose Lib., Cleveland Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsIn a perfectly pitched memoir, novelist Miller (The World Below, 2001, etc.) movingly depicts the bittersweet emotions provoked by the toll Alzheimer’s exacted on her father. He was an ordained minister and had taught Church History at the University of Chicago and Princeton. Unlike Miller’s volatile, self-absorbed mother, who took greater pleasure in privacy than in maternity, her father was quiet, reserved, and fond of spending time with his four children. He read to them, taught them outdoor skills during their summers in Maine, and had a great gift for listening, giving their conversation his "full, generous, disinterested attention." After the author became a parent herself, she grew closer to her mother, who died suddenly, at the age of 60, in 1979. Miller resumed her old intimacy with her father, showing him her short stories, which were beginning to be published and spending summers with him in New Hampshire fixing up the house he had bought there. In retrospect, she recognizes that he already had Alzheimer’s. He confessed to being unable to read or write since his wife died, but Miller attributed those symptoms to depression. He wore the same clothes often, but he had always been an abstracted man, caught up in the world of ideas. Six years after her mother died, Miller got a phone call from the police, who had found her father wandering around the countryside in western Massachusetts. He was clearly disoriented, and his children realized he could no longer live alone. Miller eventually became responsible for him, visiting almost daily at the nursing home and monitoring his care. She affectingly details his long decline as well as what is known about Alzheimer’s. Writing thismemoir, she finds, brings her consolation; her father, she realizes, had never needed it because of his faith: "for him his life and death already made sense." A loving and eloquent tribute from a talented daughter. (11 photos) First printing of 75,000; Book-of-the-Month Club alternate selection\ \