The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany

Stephen Ambrose is the acknowledged dean of the historians of World War II in Europe. In three highly acclaimed, bestselling volumes, he has told the story of the bravery, steadfastness, and ingenuity of the ordinary young men, the citizen soldiers, who fought the enemy to a standstill -- the band of brothers who endured together. The very young men who flew the B-24s over Germany in World War II against terrible odds were yet another exceptional band of brothers, and, in The Wild Blue,...

Search in google:

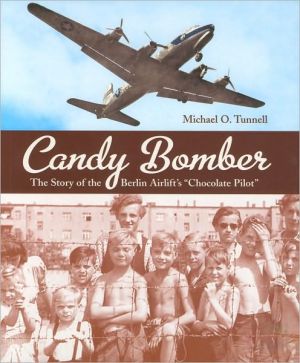

Stephen Ambrose is the acknowledged dean of the historians of World War II in Europe. In three highly acclaimed, bestselling volumes, he has told the story of the bravery, steadfastness, and ingenuity of the ordinary young men, the citizen soldiers, who fought the enemy to a standstill -- the band of brothers who endured together. The very young men who flew the B-24s over Germany in World War II against terrible odds were yet another exceptional band of brothers, and, in The Wild Blue, Ambrose recounts their extraordinary brand of heroism, skill, daring, and comradeship with the same vivid detail and affection. Ambrose describes how the Army Air Forces recruited, trained, and then chose those few who would undertake the most demanding and dangerous jobs in the war. These are the boys -- turned pilots, bombardiers, navigators, and gunners of the B-24s -- who suffered over 50 percent casualties. With his remarkable gift for bringing alive the action and tension of combat, Ambrose carries us along in the crowded, uncomfortable, and dangerous B-24s as their crews fought to the death through thick black smoke and deadly flak to reach their targets and destroy the German war machine. Twenty-two-year-old George McGovern, who was to become a United States senator and a presidential candidate, flew thirty-five combat missions (all the Army would allow) and won the Distinguished Flying Cross. We meet him and his mates, his co-pilot killed in action, and crews of other planes. Many went down in flames. As Band of Brothers and Citizen Soldiers portrayed the bravery and ultimate victory of the American soldiers from Normandy on to Germany, The Wild Blue makes clear the contribution these young men of the Army Air Forces stationed in Italy made to the Allied victory. Book Magazine In 1985, George McGovern, best known for his failed presidential campaign of 1972 and for his committed opposition to the Vietnam War, told Austrian television a striking tale of his experience piloting a B-24 during World War II. During one of the thirty-five missions that McGovern flew, a bomb had gotten stuck in the bomb bay door, a situation that placed the lives of all ten men aboard the plane in jeopardy. McGovern and his crew managed to dislodge the bomb, but to their horror, they watched it fall directly on an Austrian farm. It was high noon, he recalled, and as a farm boy himself, he knew that in all likelihood, the bomb had just wiped out an entire family gathered for their midday meal. It was a moment, McGovern told the interviewer, that helped teach him about the "savage enterprise" of war that he has regretted ever since. When the report aired on television, a farmer called the station to say that it was his farm that was hit, and he wanted to absolve McGovern's conscience. As it turns out, the farmer had seen the plane approaching and rushed his wife and children to safety. What's more, so deeply did he despise Hitler that he was happy to sacrifice his property on behalf of the Allied effort. For McGovern, the call yielded "enormous release and gratification." As he later told Ambrose, "It seemed to just wipe the slate clean." McGovern's memory of those events serves as a fitting conclusion to Ambrose's new book, which unilaterally celebrates the young men who flew America's strategic bombers during the European air war. In recent years, Americans have been engaged in a heady romance with "the greatest generation." This rediscovery of the men who foughtin World War II has been fueled in no small part by Ambrose's prodigious labors. In a remarkable string of vivid histories—most notably, Band of Brothers, Citizen Soldiers and D-Day—Ambrose has done more than anyone else to remind us of the heroic struggles American soldiers endured during World War II and of the valiant cause for which they fought. "I want young people in America...to understand that freedom doesn't come free," he has said. "The blessings they've got by being Americans were paid for. And I want them to know who paid and how and what they did." Telling the story of the U.S.' creation of an enormous air force and its massive campaign of strategic bombing—an unprecedented feat of technological innovation, industrial production and military organization—Ambrose chooses to focus not on top-ranking officials but on the young men who manned the planes. Though the book draws from the recollections of many bombardiers, navigators and gunners, it centers mainly on the fresh, young men of the Fifteenth Air Force; men such as George McGovern, a twenty-two-year-old pilot from South Dakota. Like Ambrose's previous books, this is a work of unapologetic, patriotic history. He patiently describes the grueling training that the American airmen underwent and the terrifying missions they endured. He emphasizes the fact that dropping bombs was neither a safe nor a simple task and documents the airmen's memories of flying into black clouds of lethal flak, of seeing their friends and colleagues blown from the sky and of watching countless deadly mishaps and miscalculations. By its very nature, the air war tended to be faceless and abstract, and the tasks these men performed were intensely frightening. And while the book rarely has the gripping drama of Ambrose's earlier works on paratroopers and infantrymen, the author nevertheless makes sure to reiterate that to be a crew member of a B-24 required not just great skill and extraordinary stamina but profound courage. By focusing so closely on the young men who flew the planes, however, Ambrose downplays issues that are less given to the bold colors and strong emotions he seems to prefer. Honing in on the Fifteenth Air Force that flew out of Southern Italy, he need not address the far uglier air war in the Pacific, where American actions didn't always seem so virtuous. Similarly, by focusing on the young men at the bottom of the chain of command and on American forces in particular, Ambrose avoids the larger questions that other historians and military thinkers have raised: Just how effective was the Allies' campaign of strategic bombing? Did it really impair the German war effort? And to what extent did the official preference for attacking only military targets prevent American planes from engaging in the terror bombing of civilian populations? As the anecdote about McGovern's recollection of the war suggests, Ambrose isn't interested in the careful parsing of difficult issues, but rather in unabashed hero worship and nostalgia for a day when the line between good and evil seemed clearer. "McGovern, his crew and all the airmen had spent the war years not in vain," Ambrose concludes, "but in doing good work. Along with all the peoples of the Allied nations, they saved Western civilization." — Sean McCann (Excerpted Review)

The pilots and crews of the B-24s came from every state and territory in America. They were young, fit, eager. They were sons of workers, doctors, lawyers, farmers, businessmen, educators. A few were married, most were not. Some had an excellent education, including college, where they majored in history, literature, physics, engineering, chemistry, and more. Others were barely, if at all, out of high school. \ They were all volunteers. The U.S. Army Air Corps -- after 1942 the Army Air Forces -- did not force anyone to fly. They made the choice. Most of them were between the ages of two and ten in 1927, when Charles Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis from Long Island to Paris. For many boys, this was the first outside-the-family event to influence them. It fired their imagination. Like Lindbergh, they too wanted to fly.\ In their teenage years, they drove Model T Fords, or perhaps Model A's -- if they drove at all. Many of them were farm boys. They plowed behind mules or horses. They relieved themselves in outdoor privies. They walked to school, one, two, or sometimes more miles. Most of them, including the city kids, were poor. If they were lucky enough to have jobs they earned a dollar a day, sometimes less. If they were younger sons, they wore hand-me-down clothes. In the summertime, many of them went barefoot. They seldom traveled. Many had never been out of their home counties. Even most of the more fortunate had never been out of their home states or regions. Of those who were best off, only a handful had ever been out of the country. Almost none of them had ever been up in an airplane. A surprising number had never even seen a plane. But they all wanted to fly.\ There were inducements beyond the adventure of the thing. Glamour. Extra pay. The right to wear wings. Quick promotions. You got to pick your service -- no sleeping in a Navy bunk in a heaving ship or in a foxhole with someone shooting at you. They knew they would have to serve, indeed most of them wanted to serve. Their patriotism was beyond question. They wanted to be a part of smashing Hitler, Tojo, Mussolini, and their thugs. But they wanted to choose how they did it. Overwhelmingly they wanted to fly.\ They wanted to get off the ground, be like a bird, see the country from up high, travel faster than anyone could do while attached to the earth. More than electric lights, more than steam engines, more than telephones, more than automobiles, more even than the printing press, the airplane separated past from future. It had freed mankind from the earth and opened the skies.\ They were astonishingly young. Many joined the Army Air Forces as teens. Some never got to be twenty years old before the war ended. Anyone over twenty-five was considered to be, and was called, an "old man." In the twenty-first century, adults would hardly give such youngsters the key to the family car, but in the first half of the 1940s the adults sent them out to play a critical role in saving the world.\ Most wanted to be fighter pilots, but only a relatively few attained that goal. Many became pilots or co-pilots on two- or four-engine bombers. The majority became crew members, serving as gunners or radiomen or bombardiers or flight engineers or navigators. Never mind. They wanted to fly and they did.\ Copyright © 2001 by Ambrose-Tubbs, Inc.

Acknowledgments9Author's Note17Prologue21Cast of Characters25Ch. 1Where They Came From27Ch. 2Training49Ch. 3Learning to Fly the B-2477Ch. 4The Fifteenth Air Force105Ch. 5Cerignola, Italy127Ch. 6Learning to Fly in Combat153Ch. 7December 1944173Ch. 8The Isle of Capri199Ch. 9The Tuskegee Airmen Fly Cover: February 1945209Ch. 10Missions over Austria: March 1945225Ch. 11Linz: The Last Mission: April 1945237Epilogue253Notes265Bibliography279Index283

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ Master WWII military historian Stephen Ambrose, bestselling author of such classic works as Band of Brothers and D-Day, hits the front lines again with this exciting and compelling look at the courageous young men who flew the massive B-24 bombers over Germany during the last two years of World War II. \ The focus of the book is on George McGovern, the 1972 Democratic presidential candidate, who, ironically, was lambasted by the right for his anti-Vietnam stance. Here, he shines brightly as an American airborne hero, bravely piloting his huge and awkward bomber through massive German flak bombing. McGovern also comes across as a fine commanding officer, deeply caring about the men under his authority. McGovern, at the tender age of 22, wound up flying 35 missions and ultimately won the Distinguished Flying Cross.\ The B-24 was not an easy machine to fly. It had a thin aluminum skin, which made it sufficiently airworthy but terribly susceptible to attack from ground-based enemy gunfire. It was a simple machine, though -- built with one purpose in mind: dropping a maximum load of 8,800 pounds of bombs. There were no windshield wipers, so a pilot like McGovern was often forced to stick his head out the window of the plane to see where he was going! Above 10,000 feet, the only way to breathe was through an oxygen mask. There was no heat, which made the bombing runs that much more arduous. And there were no bathrooms, meaning that the pilots and their crews had to use "relief tubes."\ Ambrose goes into much useful detail on the origins of the pilots themselves. Interestingly, they were all volunteers -- the Army Air Corps (the precursor to the modern Air Force) did not want to make anyone take part in this difficult duty. They came from all walks of life. Some were college graduates, while others were still in high school. Many went straight from the farm to the airfield.\ The pilots were treated quite well by the AAC, considering that they were part of the same armed forces that tended to dehumanize servicemen in order to get the maximum use out of them. They got to wear winged insignia on their uniforms. They got extra pay. As volunteers, they knew what they were getting into, unlike the typical draftee. Most of all, they wanted to serve -- and they wanted to fly.\ Once again, Stephen Ambrose has turned his spotlight on a special and unique facet of the U.S. military and brought the heroism and courage of the American soldier back home to us. In his own way, Ambrose himself has done a great service to the American people. (Nicholas Sinisi)\ Nicholas Sinisi is the Barnes&Noble.com History editor.\ \ \ \ \ \ In 1985, George McGovern, best known for his failed presidential campaign of 1972 and for his committed opposition to the Vietnam War, told Austrian television a striking tale of his experience piloting a B-24 during World War II. During one of the thirty-five missions that McGovern flew, a bomb had gotten stuck in the bomb bay door, a situation that placed the lives of all ten men aboard the plane in jeopardy. McGovern and his crew managed to dislodge the bomb, but to their horror, they watched it fall directly on an Austrian farm. It was high noon, he recalled, and as a farm boy himself, he knew that in all likelihood, the bomb had just wiped out an entire family gathered for their midday meal. It was a moment, McGovern told the interviewer, that helped teach him about the "savage enterprise" of war that he has regretted ever since. \ \ When the report aired on television, a farmer called the station to say that it was his farm that was hit, and he wanted to absolve McGovern's conscience. As it turns out, the farmer had seen the plane approaching and rushed his wife and children to safety. What's more, so deeply did he despise Hitler that he was happy to sacrifice his property on behalf of the Allied effort. For McGovern, the call yielded "enormous release and gratification." As he later told Ambrose, "It seemed to just wipe the slate clean." McGovern's memory of those events serves as a fitting conclusion to Ambrose's new book, which unilaterally celebrates the young men who flew America's strategic bombers during the European air war. \ \ In recent years, Americans have been engaged in a heady romance with "the greatest generation." This rediscovery of the men who foughtin World War II has been fueled in no small part by Ambrose's prodigious labors. In a remarkable string of vivid histories—most notably, Band of Brothers, Citizen Soldiers and D-Day—Ambrose has done more than anyone else to remind us of the heroic struggles American soldiers endured during World War II and of the valiant cause for which they fought. "I want young people in America...to understand that freedom doesn't come free," he has said. "The blessings they've got by being Americans were paid for. And I want them to know who paid and how and what they did." \ \ Telling the story of the U.S.' creation of an enormous air force and its massive campaign of strategic bombing—an unprecedented feat of technological innovation, industrial production and military organization—Ambrose chooses to focus not on top-ranking officials but on the young men who manned the planes. Though the book draws from the recollections of many bombardiers, navigators and gunners, it centers mainly on the fresh, young men of the Fifteenth Air Force; men such as George McGovern, a twenty-two-year-old pilot from South Dakota. \ \ Like Ambrose's previous books, this is a work of unapologetic, patriotic history. He patiently describes the grueling training that the American airmen underwent and the terrifying missions they endured. He emphasizes the fact that dropping bombs was neither a safe nor a simple task and documents the airmen's memories of flying into black clouds of lethal flak, of seeing their friends and colleagues blown from the sky and of watching countless deadly mishaps and miscalculations. By its very nature, the air war tended to be faceless and abstract, and the tasks these men performed were intensely frightening. And while the book rarely has the gripping drama of Ambrose's earlier works on paratroopers and infantrymen, the author nevertheless makes sure to reiterate that to be a crew member of a B-24 required not just great skill and extraordinary stamina but profound courage. \ \ By focusing so closely on the young men who flew the planes, however, Ambrose downplays issues that are less given to the bold colors and strong emotions he seems to prefer. Honing in on the Fifteenth Air Force that flew out of Southern Italy, he need not address the far uglier air war in the Pacific, where American actions didn't always seem so virtuous. Similarly, by focusing on the young men at the bottom of the chain of command and on American forces in particular, Ambrose avoids the larger questions that other historians and military thinkers have raised: Just how effective was the Allies' campaign of strategic bombing? Did it really impair the German war effort? And to what extent did the official preference for attacking only military targets prevent American planes from engaging in the terror bombing of civilian populations? \ \ As the anecdote about McGovern's recollection of the war suggests, Ambrose isn't interested in the careful parsing of difficult issues, but rather in unabashed hero worship and nostalgia for a day when the line between good and evil seemed clearer. "McGovern, his crew and all the airmen had spent the war years not in vain," Ambrose concludes, "but in doing good work. Along with all the peoples of the Allied nations, they saved Western civilization." \ — Sean McCann \ \ (Excerpted Review)\ \ \ Library JournalA distinguished author whose recent works include Band of Brothers and Citizen Soldiers, which also focus on World War II, Ambrose prefers to tell history from the average soldier's point of view. This book follows that formula. Ironically, the main character in this war book is George McGovern, who flew 35 combat missions and won the Distinguished Flying Cross but would later become a dovish Democratic candidate for president in 1972. The book follows the training of the 22-year-old McGovern and his friends through their deployment into Italy in 1944-45. Those who made it through the demanding and often dangerous training courses would have to face the even more perilous routine of flying a B24 bomber into the heavily defended skies over Germany. Many B24 flight crews never returned. The mental fatigue of flying so many stressful missions was almost as bad as the physical danger. With books like this, Ambrose has certainly struck a popular chord. The World War II generation is thinning daily, and everyone's story should be told including McGovern's. Ambrose's narrative flows smoothly, even as he manages to cover each man's story. Recommended for public and academic libraries and subject specialists. [Previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 4/15/01.] Mark Ellis, Albany State Univ., GA Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAnother paean to the "greatest generation" of young Americans, this time focusing on the B-24 bomber crews-with special attention to the crew of the Dakota Queen, piloted by future US Senator and 1972 presidential candidate George McGovern. Ambrose (Nothing Like It in the World) took over this project from reporter Michael Takiff, who had begun work on a book about McGovern's wartime experiences. Ambrose and his editor decided to broaden the scope, and the result is this highly anecdotal biography-cum-military history whose purpose seems more to celebrate than to scrutinize. The author acknowledges that he is a McGovern partisan, so seldom is heard a discouraging word about the young South Dakota pilot's 35 combat missions-or about his character. Ambrose begins with a brief chapter about the B-24 (called the "Liberator"), describing its spartan design and the rigorous physical and psychological demands it placed on those who flew and maintained it. (He notes wistfully that only one of the craft is currently flying; virtually all were recycled after the war.) He then goes on to answer one of his questions: "From whence came such men?" He describes McGovern's background (his father was a preacher), then follows him (and others) through the arduous and highly competitive training process. McGovern arrived in Naples in September 1944 and proceeded to the base at Cerignola, where the B-24s launched their assaults on the Nazi assets, principally oil refineries and manufacturing centers. (Ambrose mentions that McGovern's group once attacked very near Auschwitz but elects to summarize FDR's position rather than enter the should-we-or-shouldn't-we? debate about bombing the deathcamp.) McGovern emerges as a skilled, courageous pilot (he earned a Distinguished Flying Cross) who made a couple of spectacular landings in perilous situations and enjoyed the respect of his colleagues. His inadvertent bombing of an Italian farmhouse troubled him for a half-century. Ambrose, as always, finds poignant details, tells powerful stories. Much nostalgia and admiration; very little analysis; virtually no censure.\ \