The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law

This book is the first to gather in a single volume concise biographies of the most eminent men and women in the history of American law. Encompassing a wide range of individuals who have devised, replenished, expounded, and explained law, The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law presents succinct and lively entries devoted to more than 700 subjects selected for their significant and lasting influence on American law.\ \ Casting a wide net, editor Roger K. Newman includes...

Search in google:

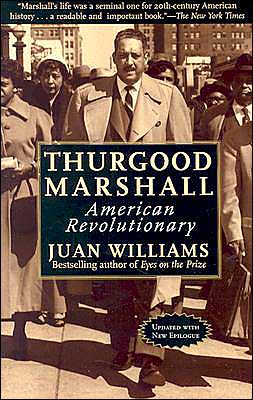

This book is the first to gather in a single volume concise biographies of the most eminent men and women in the history of American law. Encompassing a wide range of individuals who have devised, replenished, expounded, and explained law, The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law presents succinct and lively entries devoted to more than 700 subjects selected for their significant and lasting influence on American law. Casting a wide net, editor Roger K. Newman includes individuals from around the country, from colonial times to the present, encompassing the spectrum of ideologies from left-wing to right, and including a diversity of racial, ethnic, and religious groups. Entries are devoted to the living and dead, the famous and infamous, many who upheld the law and some who broke it. Supreme Court justices, private practice lawyers, presidents, professors, journalists, philosophers, novelists, prosecutors, and others—the individuals in the volume are as diverse as the nation itself. Entries written by close to 600 expert contributors outline basic biographical facts on their subjects, offer well-chosen anecdotes and incidents to reveal accomplishments, and include brief bibliographies. Readers will turn to this dictionary as an authoritative and useful resource, but they will also discover a volume that delights and entertains. Listed in The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law:John AshcroftRobert H. BorkBill ClintonRuth Bader GinsburgPatrick HenryJ. Edgar HooverJames MadisonThurgood MarshallSandra Day O’ConnorJanet RenoFranklin D. RooseveltJulius and Ethel RosenbergJohn T. ScopesO. J. SimpsonAlexis de TocquevilleScott TurowAnd more than 700 others Sara Rofofsky Marcus - Library Journal The first comprehensive, concise biographical dictionary of law-related figures in the United States from Colonial times to today, this A-to-Z provides approximately a page long and signed articles with references on judges, lawyers, law teachers, and others in law-related fields. It draws on the nearly 40 years of experience of editor Newman in studying and writing about the Supreme Court and American law while teaching at the Columbia University School of Journalism. The entries, while informative and authoritative, are not the dry writing one would expect to find in such a scholarly resource; rather, they are easy to read and engaging, making users want to find out more about additional people. Inclusion of not only biographical facts but also anecdotes and incidents regarding accomplishments gives this work a personal touch often lacking in a biographical dictionary. A drawback is the absence of cross-references between entries or the use of subject indexes and/or listings to help one find entries on specific types of people. BOTTOM LINE Unbiased in coverage, the book does not exclude those who broke the law, but rather focuses on those related to the law, whether by practicing it or by otherwise becoming involved in the field. It is a valuable addition to any academic or law library; high school libraries may want to seriously consider adding it to their collections as well. Sara Rofofsky Marcus, Queensborough Community Coll. Lib., Bayside, NY

The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law\ \ YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS\ Copyright © 2009 Yale University\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-300-11300-6 \ \ \ Chapter One\ A\ Abrahamson, Shirley S. (1933- ). State judge. Born in New York City, the daughter of Polish immigrants, Abrahamson received an A.B. (1953) from New York University, a J.D. (1956) from Indiana University, and an S.J.D. (1962) from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Katharine Hepburn's portrayal of a lawyer in the movie Adam's Rib nudged her toward a legal career. Abrahamson served as assistant director of the Legislative Drafting Research Fund at Columbia Law School from 1957 to 1960, after which she moved to Wisconsin, where her husband became a member of the zoology faculty. Her doctoral thesis under Professor J. Willard Hurst was a path-breaking study of the impact of law on the development of Wisconsin's dairy industry. She practiced law from 1962 to 1976, specializing in taxation and estate planning, and establishing herself as a model for other young women entering the legal profession. She helped organize a chapter of the Wisconsin Civil Liberties Union. In 1965 Abrahamson started teaching taxation at the University of Wisconsin Law School. She received tenure the next year, and her popularity guaranteed large classes.\ In 1976 Abrahamson was appointed to the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, its first female justice, andwas elected to full 10-year terms in 1979, 1989, and 1999. Spirited, active, and sometimes ferocious opponents did not prevent her from substantial victories each time. She gave the impression that she enjoyed the judicial election process-certainly more than her colleagues. Becoming chief justice in 1996, she was the first chief to significantly exercise the administrative responsibilities authorized by a 1977 amendment to Wisconsin's constitution. This provoked a response from several members of the court seeking to review that authority. In her 1999 election bid three colleagues endorsed her opponent.\ A deep sense of fairness drives her jurisprudence, and some of her most notable opinions have been dissents. The U.S. Supreme Court in Welsh v. Wisconsin (1984), reversing a Wisconsin decision that upheld entering a man's home without a warrant to arrest him for a minor traffic offense, showed the marks of her dissenting opinion, which faulted the entry. In the field of family law her decision in Watts v. Watts (1987), concerning an unmarried man and woman who had lived together for 12 years and had children while the man ran a business and the woman cared for their home, established the woman's right to a property division of the assets accumulated during their cohabitation. The division of the property might rest on theories of contract, constructive trust, and unjust enrichment. The opinion applies a sophisticated analysis of these theories and rejects the argument that the parties' failure to marry bars a division of property.\ In Button v. Button (1986), an Abrahamson opinion reversed a ruling upholding the terms of a marital agreement signed five years after the marriage. Her opinion rested on a finding that the agreement could fail if the trial court found it "inequitable." Similarly, in 2005 she ruled that a cap on noneconomic damages in medical malpractice cases was unconstitutional. Her work has always been her hobby. Informal, she likes people to call her by her first name. As an administrator she expanded various legal services, and in her reelection campaigns she had the support of sheriffs and police chiefs as well as civil libertarian groups.\ GORDON B. BALDWIN\ Abram, Morris B. (1918-2000). Lawyer. Abram was born in Fitzgerald, Ga., and graduated from the University of Georgia in 1938 and the University of Chicago Law School in 1940. After serving in military intelligence during World War II, he was a member of the prosecution at the Nuremburg trials in 1946 and then attended Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar. Abram practiced law in Atlanta, largely representing railroads, starting in 1948.\ Overturning Georgia's "county unit" election rule became a passion for Abram. This law gave disproportionate weight to rural areas by requiring that election results be measured by counties as a bloc and helped perpetuate segregation. Abram felt its impact directly when he sought the Democratic nomination for Congress in 1954, winning the popular vote but losing two of three counties and therefore the primary. Remaining in Georgia largely to abolish the law, he challenged it in the courts and argued the case when it reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1963. "A vote is a vote is a vote," he told the justices. In Gray v. Sanders the Court ruled the county unit law unconstitutional. "If I die," Abram wrote in his autobiography, "my epitaph can read, 'He restored democracy to Georgia.'"\ In 1960, on behalf of John F. Kennedy's campaign for president, Abram helped negotiate the release of Martin Luther King, Jr., from a Georgia jail and engineered King's father's endorsement of Kennedy. Abram was appointed general counsel of the Peace Corps by Kennedy in 1961, then joined the New York law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison, with which he was thereafter associated. He helped plan President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty but rejected Johnson's offer in 1964 to be the first chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.\ A federal judgeship was Abram's initial goal. It was politically impossible in Georgia, and in New York he turned down an offer in 1965. Abram served as the U.S. representative to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights from 1965 to 1968 and planned to run for the U.S. Senate in 1968, but his position on Vietnam was not acceptable to Johnson and he did not run. As president of Brandeis University from 1968 to 1970, he opposed demands for a black studies program and unspecified racial preferences. He abruptly resigned to run for the Democratic nomination for the Senate; his support was minimal, and he quickly dropped out of the race.\ In 1983 President Ronald Reagan nominated Abram to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He served as its vice chairman from 1984 to 1986. Equal pay for women "is a debatable social and economic policy to redistribute income-a concept foreign to the meaning of civil rights," Abram wrote in 1986. "I could never support racial preference," he said later. "If you discriminate against a group, you are endangering all minority groups."\ In 1989 President George H. W. Bush appointed Abram as the U.S. permanent representative to the U.N. in Europe. He remained in the post until 1993, when he founded and became chairman of U.N. Watch, one of whose purposes was the curbing of anti-Semitism in the U.N.; Abram was long active in Jewish affairs. "A stand-up position [is] a mark of good character," he said. It was a creed that along with his unrelenting persistence often rankled opponents, but it helped Abram to achieve his goals.\ ROGER K. NEWMAN\ Abrams, Floyd (1936- ). Lawyer. Born in New York City, Abrams grew up in Queens as an avid Yankees fan. A nail-biter and sometime stutterer, he excelled as a debater at Cornell (B.A., 1956) and in moot court at Yale Law School (LL.B., 1959) but showed scant interest in issues involving press freedom. Indeed, he was a "premature neo-conservative," he recalled. His senior thesis at Cornell concerned the ongoing struggle between the press and the courts, and Abrams argued that the press was in the wrong-a position that he has never taken in his long career as a litigator with the New York firm Cahill Gordon and Reindel, which he joined in 1963 after clerking for Delaware federal judge Paul Leahy.\ The 1960s were an auspicious time to begin the practice of free press law. Only a handful of lawyers specialized in the area, and, as Abrams later wrote, "By the time I began to practice First Amendment law in the late 1960s, the Supreme Court had decided only a few cases upon which a First Amendment legal defender could rely." Abrams was doing a growing amount of work for NBC, a long-time client of his firm. Then came a career-changing break.\ In 1971, while representing NBC, Abrams urged his former law professor, Alexander Bickel, to write a friend-of-the-court brief favoring the press's right to conceal anonymous sources. Just as this was happening, the New York Times began publishing what came to be known as the Pentagon Papers. The newspaper's long-time firm refused to represent the paper, which quickly turned to Bickel and Abrams. Within 15 days, the issue zoomed to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the government could not prevent the Times and other newspapers from publishing highly classified national security information that had been made available by a confidential source.\ That victory catapulted an obscure junior partner to national eminence. Abrams became involved in many of the most important cases in which the rights of the press have been defined. To date, he has argued 12 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Moreover, through clear and cogent articles, calm and convincing speeches, and the pithy quotes he has generously provided journalists, Abrams has become the premier "explainer" of developments in First Amendment law.\ One of his most stinging losses came during the second term of George W. Bush. At the pinnacle of his career, in May 2005, Abrams was honored by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. Presenting the award were Matthew Cooper of Time magazine and Judith Miller of the New York Times. For a year, Abrams had tried to stop a special prosecutor seeking testimony about Cooper's and Miller's confidential sources, as a federal grand jury investigated who had leaked the name of an employee of the Central Intelligence Agency. A month earlier, Time had dismissed Abrams as its head lawyer in the case, and by summer, Miller, who had also hired a criminal lawyer, was in jail.\ This case-the biggest test of confidential sources in a generation-ended in an inconclusive mess for the press. Abrams, consistent to his principles, took the "absolutist" position that journalists should not have to disclose their sources. But his advocacy failed, at a time when the public and the courts were unwilling to afford special treatment to the press. One of Abrams's most appealing personal traits is his modesty, and as he related in his memoir, unlike almost all other giants of the law, "I have lost as well as won cases, made errors as well as hit home runs."\ TOM GOLDSTEIN\ Acheson, Dean (1893-1971). Lawyer, government official, and secretary of state. Acheson exemplified the best of the small group of lawyers who during the twentieth century alternated private practice with high office in the conduct of American foreign policy. His career began propitiously. Born in Middletown, Conn., son of a British-born Episcopalian bishop and an energetic Canadian-born mother, he graduated from Yale in 1915 and from Harvard Law School in 1918, where his lifelong intellectual bond and friendship with Professor Felix Frankfurter began. Frankfurter's recommendation led to Acheson's two-year clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis. Acheson was also enriched and enthralled by frequent conversations with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.\ In 1922 Acheson decided against teaching, inquired about a position as counsel to the United Mine Workers, and joined the young firm of Covington and Burling (to use its principal name over the years). He skipped the routine work of typical associates and began at the top with a successful argument before The Hague Court in 1922 on behalf of the claim of the Norwegian government for fair compensation from the United States for ships requisitioned during World War I. By 1926 Acheson was a partner. In 1933, as acting secretary of the treasury in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, he resigned in protest over what he considered FDR's illegal and unethical devaluing of the dollar. Back at the firm, he handled high-profile cases, often of an international nature and involving the U.S. government and major corporations. He said no to conservative Democrats who asked him to oppose Roosevelt's reelection.\ Then came the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939. Acheson was a leading pro-British interventionist from the start. If the United States did not rearm, support Britain, and do all that was necessary to defeat Germany, then "surrounded by armed and hostile camps, we will have to conduct our economy as best we can and attempt to preserve the security and dignity of human life and the freedom of the human spirit." In 1940 with Benjamin V. Cohen he discovered a legal justification in old World War I legislation for providing 50 destroyers to Great Britain in return for sites for American bases on British islands from Newfoundland to the West Indies.\ In 1941 he returned to government service as an assistant secretary of state, remaining in the State Department (except for a short time in 1947-48) through his four years as President Harry S. Truman's secretary of state (1949-53). To repeat the title of his detailed, Pulitzer Prize-winning 1969 account of those years, he was "present at the creation" of fundamental American policy in the Cold War. He built strong alliances, zealously protected and enhanced presidential power, concentrated on the connections of military and economic power, disdained theory, and did not tolerate intolerable "primitives" such as Senator Joseph McCarthy.\ In 1953 Acheson returned again to the old firm and for his remaining years practiced less law-he argued 15 cases overall before the Supreme Court-but wrote scores of articles and books. When the Democrats were out of power during the Eisenhower years, he advised the party on foreign policy. When Democrats returned, he advised and undertook special missions for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remained liberal in domestic politics but turned increasingly conservative in nostalgia for the stability of the old British Empire.\ Acheson long served as a senior fellow (trustee) of Yale University. Deploring what he considered the shallow and self-promoting antics of certain law school professors, in the mid-1950s he contributed to the school's shift toward a more diverse and centrist faculty. Tall, mustachioed, invariably elegantly attired, and with a lively, often caustic, wit, Acheson cut a striking figure. He died from a sudden stroke at his Maryland country home.\ GADDIS SMITH\ Adams, John (1735-1826). Lawyer, revolutionary, and president of the United States. Like Thomas Jefferson, with whom he is inevitably compared, Adams had a relatively brief formal legal career, a prelude to his much longer and more important service as a diplomat and statesman. Born and reared in Braintree, Mass., the son of a farmer, Adams graduated from Harvard in 1755, read law in Worcester, Mass., while he taught school to support himself, and practiced law from 1758, when he was admitted to the bar, to 1774, when he left for Philadelphia and the First Continental Congress. Like many in the founding generation, he bore the distinctive impress of the provincial lawyer for the rest of his life.\ Ambitious, both socially and intellectually, Adams did his best to master bodies of the law that would allow him to circulate in elite legal circles. He would admit to himself that he did not learn much from the Latin volumes of Justinian and the other civilians he pored over, but study them he did. He began his career at home, in Braintree, where family connections meant something, but his first case was a flop and Adams confided to his diary his "fear of having it thought that I was incapable of drawing the Writt." Only after he had established himself in Braintree-and married up, by taking as his wife Abigail Smith, whose mother was a Quincy-did he venture into the deeper waters of Boston practice. Properly respectful to his seniors at the bar, he also became involved in Whig politics, particularly in 1765 with the Stamp Act. Here his learning in some of the more obscure areas of legal knowledge served him well. His Dissertation on the Feudal and the Canon Law (1765) helped to establish him as one of the more learned defenders of colonial rights.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Contents Introduction....................xiThe Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law....................1List of Contributors....................611Photograph Credits....................621

\ The Washington Times"[A] marvelous, multifaceted pointilliste portrait of the good, the bad and the ugly faces of American jurisprudence through the centuries. . . . The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law is a delightfully engaging read. At times entertaining, at others chilling, it is consistently informative and instructive. Once you dip into it, you will find it hard to stop."—Martin Rubin, The Washington Times\ — Martin Rubin\ \ \ \ \ \ ChoiceChosen as an Outstanding Academic Title for 2009 by Choice Magazine\ \ \ Law Library Journal“. . . this little gem manages to be scholarly yet surprisingly entertaining at the same time.”--Law Library Journal\ \ \ \ \ \ The Washington Times"[A] marvelous, multifaceted pointilliste portrait of the good, the bad and the ugly faces of American jurisprudence through the centuries. . . . The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law is a delightfully engaging read. At times entertaining, at others chilling, it is consistently informative and instructive. Once you dip into it, you will find it hard to stop."—Martin Rubin, The Washington Times\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThe first comprehensive, concise biographical dictionary of law-related figures in the United States from Colonial times to today, this A-to-Z provides approximately a page long and signed articles with references on judges, lawyers, law teachers, and others in law-related fields. It draws on the nearly 40 years of experience of editor Newman in studying and writing about the Supreme Court and American law while teaching at the Columbia University School of Journalism. The entries, while informative and authoritative, are not the dry writing one would expect to find in such a scholarly resource; rather, they are easy to read and engaging, making users want to find out more about additional people. Inclusion of not only biographical facts but also anecdotes and incidents regarding accomplishments gives this work a personal touch often lacking in a biographical dictionary. A drawback is the absence of cross-references between entries or the use of subject indexes and/or listings to help one find entries on specific types of people. BOTTOM LINE Unbiased in coverage, the book does not exclude those who broke the law, but rather focuses on those related to the law, whether by practicing it or by otherwise becoming involved in the field. It is a valuable addition to any academic or law library; high school libraries may want to seriously consider adding it to their collections as well.—Sara Rofofsky Marcus, Queensborough Community Coll. Lib., Bayside, NY\ \ —Sara Rofofsky Marcus\ \