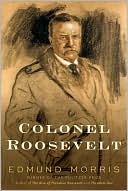

Theodore Rex

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • “A shining portrait of a presciently modern political genius maneuvering in a gilded age of wealth, optimism, excess and American global ascension.”—San Francisco Chronicle WINNER OF THE LOS ANGELES TIMES BOOK PRIZE FOR BIOGRAPHY • “[Theodore Rex] is one of the great histories of the American presidency, worthy of being on a shelf alongside Henry Adams’s volumes on Jefferson and Madison.”—Times Literary Supplement Theodore Rex is the story—never fully told...

Search in google:

In Edmund Morris' sequel to his Pulitzer Prize-winning first book on Theodore Roosevelt, Roosevelt's great deeds, gifts, and energy are on conspicuous display. Roosevelt's presidency was imperial, and he shaped policies and events according to his will despite the opposition of Wall Street, the white South, and other interests. Among his achievements were the acquisition of the Panama Canal and the Philippines, the creation of numerous national parks and monuments, and the prosecution of trusts and monopolies. Theodore Roosevelt comes off as one of our strongest, best-willed, and most admirable presidents. New York Times - Richard Brookhiser In the second installment of his megabiography of Theodore Roosevelt, Edmund Morris writes with a breezy verve that perfectly suits his subject.

Chapter 1\ The First Administration: 1901-1904\ The epigraphs at the head of every chapter are by "Mr. Dooley," Theodore Roosevelt's favorite social commentator.\ \ The Shadow of the Crown\ I see that Tiddy, Prisidint Tiddy-here's his health-is th' youngest prisidint we've iver had, an' some iv th' pa-apers ar-re wondherin' whether he's old enough f'r th' raysponsibilities iv' th' office.\ On the morning after McKinley's interment, Friday, 20 September 1901, a stocky figure in a frock coat sprang up the front steps of the White House. A policeman, recognizing the new President of the United States, jerked to attention, but Roosevelt, trailed by Commander Cowles, was already on his way into the vestibule. Nodding at a pair of attaches, he hurried into the elevator and rose to the second floor. His rapid footsteps sought out the executive office over the East Room. Within seconds of arrival he was leaning back in McKinley's chair, dictating letters to William Loeb. He looked as if he had sat there for years. It was, a veteran observer marveled, "quite the strangest introduction of a Chief Magistrate . . . in our national history."\ As the President worked, squads of cleaners, painters, and varnishers hastened to refurbish the private apartments down the hall. He sent word that he and Mrs. Roosevelt would occupy the sunny riverview suite on the south corner. Not for them the northern exposure favored by their predecessors, with its cold white light and panorama of countless chimney pots.\ A pall of death and invalidism hung over the fusty building. Roosevelt decided to remain at his brother-in-law's house until after the weekend. It was as if he wanted the White House to ventilate itself of the sad fragrance of the nineteenth century. Edith and the children would breeze in soon enough, bringing what he called "the Oyster Bay atmosphere."\ At eleven o'clock he held his first Cabinet meeting. There was a moment of strangeness when he took his place at the head of McKinley's table. Ghostly responsibility sat on his shoulders. "A very heavy weight," James Wilson mused, "for anyone so young as he is."\ But the President was not looking for sympathy. "I need your advice and counsel," he said. He also needed their resignations, but for legal reasons only. Every man must accept reappointment. "I cannot accept a declination."\ This assertion of authority went unchallenged. Relaxing, Roosevelt asked for briefings on every department of the Administration. His officers complied in order of seniority. He interrupted them often with questions, and they were astonished by the rapidity with which he embraced and sorted information. His curiosity and apparent lack of guile charmed them.\ The President's hunger for intelligence did not diminish as the day wore on. He demanded naval-construction statistics and tariff-reciprocity guidelines and a timetable for the independence of Cuba, and got two visiting Senators to tell him more than they wanted to about the inner workings of Congress. In the late afternoon, he summoned the heads of Washington's three press agencies.\ "This being my first day in the White House as President of the United States," Roosevelt said ingratiatingly, "I desired to have a little talk with you gentlemen who are responsible for the collection and dissemination of the news."\ A certain code of "relations," he went on, should be established immediately. He glanced at the Associated Press and Sun service representatives. "Mr. Boynton and Mr. Barry, whom I have known for many years and who have always possessed my confidence, shall continue to have it." They must understand that this privilege depended on their "discretion as to publication." Unfortunately, he could not promise equal access to Mr. Keen of the United Press, "whom I have just met for the first time."\ Boynton and Barry jumped to their colleague's defense. Roosevelt was persuaded to trust him, but warned again that he would bar any White House correspondent who betrayed him or misquoted him. In serious cases, he might even bar an entire newspaper. Barry said that was surely going too far. Roosevelt's only reply was a mysterious smile. "All right, gentlemen, now we understand each other."\ Much later that evening, after a small dinner with friends in the Cowles house on N Street, the President allowed himself a moment or two of querulousness. "My great difficulty, my serious problem, will meet me when I leave the White House. Supposing I have a second term . . ."\ Commander Cowles, replete with roast beef, sank deep into leather cushions and folded his hands over his paunch. He paid no attention to the cataract of talk pouring from the walnut chair opposite. For years he had benignly suffered his brother-in-law's fireside oratory; he was as deaf to Rooseveltian self-praise as he was to these occasional moments of self-doubt. How like Theodore to worry about moving out of the White House before moving in! The Commander's eyes drooped. His breathing grew rhythmic; he began to snore.\ "I shall be young, in my early fifties," Roosevelt was saying. "On the shelf! Retired! Out of it!"\ Two other guests, William Allen White and Nicholas Murray Butler, listened sympathetically. Prodigies themselves-White, at thirty-three, had a national reputation for political journalism, and Butler, at thirty-nine, was about to become president of Columbia University-they were both aware that they had reached the top of their fields, and could stay there for another forty years. Roosevelt was sure of only three and a half. Of course, the power given him dwarfed theirs, and he might win an extension of it in 1904. But that would make its final loss only harder to bear.\ So Butler and White allowed the President to continue lamenting his imminent retirement. They interrupted only when he grew maudlin-"I don't want to be the old cannon loose on the deck in the storm!"\ Undisturbed by the clamor of younger voices, Commander Cowles slept on.

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ Theodore Roosevelt and his two-term presidency (1901-9) deserve a king-size, seize-the-man biography -- and Edmund Morris has provided one. "TR" typifies the "can do" American; his famous maxim, of course, was "Speak softly but carry a big stick." Morris presents eyewitness history through the voices of the makers and shakers. His exhilarating narrative will captivate readers, providing welcome confirmation that this nation can produce presidents who bring leadership to great issues, hold to their purpose, and shape the destinies of nations. \ President McKinley's assassination brought the 43-year-old TR a challenging presidency, one to which Morris is a clearsighted guide. At home, TR had to persuade Congress to curb competition-stifling corporate trusts, monopolistic transcontinental railroads, and unhygienic food industries that saw consumers as sheep. He also faced labor and racial strife. Abroad, the American presence in Cuba and the Philippines brought criticism, the Russo-Japanese conflict threatened major power shifts in the Far East and Europe, and a politically and financially fraught decision on the Central American canal route -- Panama or Nicaragua? -- had to be made. TR rose to every challenge. Despite the demands of family and social life, he read, wrote, and traveled extensively. Not least, TR put national parks and conservation of natural resources on the legislative agenda.\ All TR's notable contemporaries -- including historian Henry Adams, naturalists John Burroughs and John Muir, robber barons E. H. Harriman and James J. Hill, poet Oliver Wendell Holmes, financier J. P. Morgan, fellow politician William Howard Taft, civil rights leader Booker T. Washington, and novelist Owen Wister -- appear onstage, their clear voices projecting the excitement of the day.\ Morris is blessed with the imagination and skills to write gripping popular history. He doesn't dilute but illuminates events in presenting an account that immediately sparks interest and captures the mind. Readers will note that American interventionism abroad (today's major issue) was much debated during TR's presidency, when major interventional imperatives challenged the new superpower's tradition of relative restraint in foreign affairs.\ Theodore Rex is the long-awaited second volume of the TR saga. Morris delivered the first volume, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, in 1979. It won a Pulitzer Prize; Theodore Rex is a solid bet for another. (Peter Skinner)\ Peter Skinner lives in Manhattan.\ \ \ \ \ \ Richard BrookhiserIn the second installment of his megabiography of Theodore Roosevelt, Edmund Morris writes with a breezy verve that perfectly suits his subject. \ — New York Times\ \ \ Michael LindEdmund Morris' Theodore Rex is every bit as much a masterpiece of biographical writing as his first installment, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, which won the Pulitzer Prize and the American Book Award. \ — Washington Post Book World\ \ \ \ \ From The CriticsTheodore Roosevelt is one of America's best-remembered presidents—but why? Though his seven-and-a-half-year term of office was far from uneventful, most of his specific achievements have faded from our collective memory. \ He won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the Russo-Japanese War; he appointed Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. to the Supreme Court; he was the first president to invite a black man to dinner at the White House. Without him, the Panama Canal might not have been dug or the Grand Canyon turned into a national park. If you knew any of these things, you are way ahead of the game. Yet "TR" (as he was known in his day) has somehow remained an American icon, one sufficiently evocative that political commentator David Brooks, seeking to put into historical context the speech given by George W. Bush to Congress after the World Trade Center disaster, chose to quote from Roosevelt's 1899 speech "The Strenuous Life": "We of this generation do not have to face a task such as that our fathers faced, but we have our tasks, and woe to us if we fail to perform them!"\ Edmund Morris won a Pulitzer Prize in 1980 for The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, but a funny thing happened on the way to that fine book's long-awaited sequel. He was chosen as Ronald Reagan's authorized biographer and granted fly-on-the-wall access to the White House, out of which he spun a partly fictionalized account of Reagan's life and times that threw readers and reviewers for a loop. For all its peculiarities, Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan was a much better book than is generally realized, but those unable to accept its novelistic license will be comforted to learn that Theodore Rex isnothing more—or less—than a solid, straightforward biography, exhaustively researched and excitingly written.\ To be sure, it is hard to write boringly about Roosevelt, one of the few American presidents who could fairly be described as eccentric to the point of strangeness. His pince-nez glasses, ginger-colored mustache and muzzlelike face were a cartoonist's wildest dream, and he acted as oddly as he looked, tearing around Washington with an enthusiasm neatly summed up by Cecil Spring Rice, one of his oldest friends: "You must always remember that the President is about six." To H.G. Wells, Roosevelt seemed "to be echoing with all the thought of his time, he has receptivity to the point of genius." Mark Twain, on the other hand, was struck by his mercurial energy: "He flies from one thing to another with incredible dispatch.... Each act of his, and each opinion expressed, is likely to abolish or controvert some previous act or expressed opinion." For those who continued to cling to the sedate manners of an earlier day, that energy seemed almost diabolical. "The devil is whirling me round," complained the aristocratic Henry Adams, "in the shape of a grinning fiend with tusks and eye-glasses."\ Yet Roosevelt's temperamental extremism, as Morris rightly observes, was placed in the service of the political instincts of a natural compromiser: "As always in situations involving extremes, Roosevelt's instinct was to seek out the center." Born into upper-middle-class comfort, he entered politics out of a sense of noblesse oblige, then discovered that he had a knack for its cut and thrust. Unpersuaded by the sink-or-swim gospel of laissez-faire economics, he concluded that big government (big, at least, by the modest standards of 1901) could make America a better place in which to live, and he set out to drag the wealth-worshipping old guard of the Republican Party into the twentieth century. Though he loved to talk tough, politics taught him to take what he could get and brag about it, and he happily settled for such incremental measures as the Pure Food Act of 1906 instead of insisting on radical reforms that could never have gotten through Congress.\ Was Theodore Roosevelt the inventor of moderate Republicanism? That is the clear implication of Theodore Rex, but Morris never makes the point explicitly, and this is one of the book's few weaknesses (along with a too-fancy prologue in which we see America in 1901 through the eyes of the newly inaugurated Roosevelt). Morris is so interested in showing us Roosevelt as he looked to his contemporaries that he fails to supply enough of the clarifying perspective of hindsight. Presumably his just-the-facts-ma'am approach is to some extent a response to the furious criticisms of Dutch, but some will doubtless feel that Theodore Rex errs in the opposite direction.\ Even so, this is a marvelously rich and readable book, a bit too long but not grossly so, and you will put it down knowing why Roosevelt has held on to his secure place in America's fast-shrinking historical imagination. For Morris, Roosevelt's singular achievement—no less enduring than the five national parks for whose creation he was chiefly responsible—was to have "left behind a folk consensus that he had been the most powerfully positive American leader since Abraham Lincoln." As legacies go, that beats Camelot, Vietnam, Watergate and Monica Lewinsky.\ —Terry Teachout\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe second entry in Morris's projected three-volume life of Theodore Roosevelt focuses on the presidential years 1901 through early 1909. Impeccably researched and beautifully composed, Morris's book provides what is arguably the best consideration of Roosevelt's presidency ever penned. Making good use of TR's private and presidential papers as well as the archives of such protégés as John Hay, William Howard Taft, Owen Wister and John Burroughs Morris marshals a rich array of carefully chosen and beautifully rendered vignettes to create a dazzling portrait of the man (the youngest ever to hold the office of president). Morris proves the perfect guide through TR's eight breathless, fertile years in the White House: years during which the doting father and prolific author conserved millions of Western acres, swung his "big stick" at trusts and monopolies, advanced progressive agendas on race and labor relations, fostered a revolution in Panama (where he sought to build his canal), won the Nobel Peace Prize for mediating an end to the Russo-Japanese War and pushed through the Pure Food and Drug Act. John Burroughs once wrote that the hypercreative TR "was a many sided man, and every side was like an electric battery." In the end, Morris succeeds brilliantly at capturing all of TR's many energized sides, producing a book that is every bit as complex, engaging and invigorating as the vibrant president it depicts. Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalWhen Vice President Theodore Roosevelt succeeded the assassinated William McKinley, his conservative critics feared a precipitous presidency. But as shown by Morris's second volume on the "Bully" president, what emerged instead was a balanced leader who deserves being ranked among America's top five chief executives. There was universal praise for The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, the first volume of Morris's TR biography, which claimed both the Pulitzer Prize and the American Book Award in 1980. After his controversial Dutch: A Biography of Ronald Reagan, Morris returns to TR and his traditional acclaimed method, which is stylistically eloquent and historically balanced. Morris shows how Roosevelt adapted Abraham Lincoln's wartime presidency as his own model for transforming America's domestic and international agendas. His two major miscalculations were his premature announcement declining a second complete term and the handling of the Brownsville Affair, when he gave dishonorable discharges to all 167 men from three black companies stationed near Brownsville, TX, when they refused to identify 12 members who had retaliated against discriminatory practices in the town. Morris excels at placing TR in the context of his time, showing how he outmaneuvered powerful but ossified opponents from the Gilded Age and trumped isolationists by averting war, in the process winning the first Nobel Peace Prize. He also set the standard for the Hyde Park Roosevelts, whose emulation of his "accidental" presidency a generation later was perhaps his ultimate contribution to democracy. Essential for all libraries.-William D. Pederson, Louisiana State Univ., Shreveport Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsIn a sequel to the Pulitzer-winning biography of Teddy Roosevelt's earlier years (The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt), Morris celebrates his tenure in the Oval Office, lauding him as the most popular and energetic chief executive of the early modern era. Morris views Roosevelt as the next great president to succeed Lincoln. While his predecessor, William McKinley, represented dour 19th-century values, Roosevelt was more akin to the industrialization that was turning the US into a global power. He was a dynamic reformer who acted first and asked questions later. The author runs through the many irons Roosevelt always had in the fire, using each to show how his personal magnetism, political canniness, intelligence, and force of will earned him a bevy of successes and almost no significant defeats. On the domestic front, Teddy mastered the art of the end run around his political enemies, disarming orthodox Republicans by arguing that they support his trust-busting initiatives or else face the chaos of labor uprisings and quieting labor by throwing them bones designed to least infuriate management. In foreign relations, his personal magnetism and Navy-enlarging policies earned him, and the country, the respect of the great powers. He fended off German encroachments on Venezuela, ensured that the Panama Canal became a reality, and negotiated peace between Russia and Japan. Morris also devotes much attention to Roosevelt's physical exploits, which later influenced his conservation efforts. He was constantly climbing in Rock Creek Park, swimming nude in the Potomac, and boxing or practicing martial arts with members of his cabinet. To blow off steam he hunted, often in the South, where hewas seen as too friendly toward African-Americans. Because Democrats receive little attention here, one wonders how Morris might have rendered their criticisms. A boosterish rendering of a potent head of state.\ \ \ \ \ From the Publisher“In Edmund Morris, a great president has found a great biographer. . . . Every bit as much a masterpiece of biographical writing as The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, which won the Pulitzer Prize.” —The Washington Post\ “As a literary work on Theodore Roosevelt, it is unlikely ever to be surpassed. It is one of the great histories of the American presidency, worthy of being on a shelf alongside Henry Adams’s volumes on Jefferson and Madison.” —Times Literary Supplement\ “Take a deep breath and dive into Theodore Rex, Edmund Morris’s sequel to his 1979 masterpiece, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. . . . He writes with a breezy verve that makes the pages fly.” —The New York Times Book Review\ “A shining portrait of a presciently modern political genius maneuvering in a gilded age of wealth, optimism, excess and American global ascension.” —San Francisco Chronicle\ “Roosevelt is a biographer’s dream, an epic character not out of place in an adventure novel." —The Christian Science Monitor\ \ \