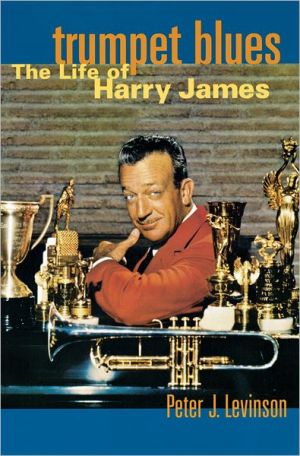

Trumpet Blues: The Life of Harry James

Swing is back in style, and with it a renewed interest in the Big Band Era. And few players dominated that era more than Harry James, whose soaring trumpet solos and romantic hit tunes influenced popular music for a generation. Now, Peter J. Levinson, who knew Harry James personally, has written a revealing biography of this jazz icon, based on nearly 200 interviews with musicians and friends.\ Harry James led a truly colorful life, and in Trumpet Blues Levinson captures it all. Beginning...

Search in google:

Swing is back in style, and with it a renewed interest in the Big Band Era. And few players dominated that era more than Harry James, whose soaring trumpet solos and romantic hit tunes influenced popular music for a generation. Now, Peter J. Levinson, who knew Harry James personally, has written a revealing biography of this jazz icon, based on nearly 200 interviews with musicians and friends. Harry James led a truly colorful life, and in Trumpet Blues Levinson captures it all. Beginning with James's childhood in a traveling circus, we follow the young trumpeter's meteoric rise in the 1930s and witness his electrifying performances with the Benny Goodman Orchestra. We see how James formed his own band in 1939, an incubator for many pop music stars of the 1940s and '50s, including Frank Sinatra, Connie Haines, Dick Haymes, Helen Forrest, and Kitty Kallen. Combined with James's superb musicianship, peerless trumpet technique and talented sidemen, this stellar group dominated the war years and the immediate post-war period. And James himself, especially after his marriage to film goddess Betty Grable, became one of America's most famous personalities and lived like true Hollywood royalty. Levinson describes their twenty-two-year marriage with insight and sympathy. But he shows how James's marriage—and his triumphant late-1950s comeback in Nevada's casinos—were slowly undermined by his penchant for compulsive gambling, womanizing, and alcoholism. He gives us the inside story of James's sybaritic life style, and probes the profound psychological reasons for James's destructive behavior. The first biography ever written on Harry James, Trumpet Blues is a scintillating portrait of Swing's brightest star—his life, his loves, and the music that defined an era. Wall Street Journal - Terry Teachout Harry James, like Nat Cole, was a jazz master. If you doubt it, read Triumpet Blues

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ Everette and Maybelle\ \ \ Albany, Georgia, lies 180 miles southeast of Atlanta. Today, to make the trip by car, one would drive forty miles from Cordele on Route 300 and then pick up I-75's four-to-six-lane highway for the remainder. Back in 1916, however, this highway was merely a dirt road, and Albany was home to 12,000 residents as compared to 90,000 today.\ It was here, on March 15, 1916, that Everette and Maybelle James welcomed a nine-pound son, Harry Haag James, at the St. Nicholas Hotel, which was located next door to the Albany jail. In that year, Everette and Maybelle James were two of the principal performers in the Mighty Haag Shows—a "mud show"—a traveling circus that only played small towns touring the South and Southeast. Everette was the circus's bandmaster and Maybelle was a featured trapeze artist. The story goes that Maybelle continued performing on the trapeze until only a few weeks before the birth of their son. The Jameses and their new son remained in Albany only sixteen days before the Haag wagons moved on up the dirt road to Atlanta for another engagement.\ The Haag circus poster would appear on tobacco barns and smokehouses along the dusty roads, particularly in the Appalachian South, and this would herald the coming of spring. Ernest Haag's one-ring circus was considered the favorite circus of the region. The price of admission was fifty cents—a bargain.\ It played many of the hill country towns in Kentucky and Tennessee. When the show played at night, on occasion some of the citizens of the townwould warn the performers that the hill folk would be coming down looking for a fight and would urge that they immediately cut the tent ropes and move on. In some places the local feuds spilled over onto the circus grounds. As a matter of fact, the Hatfields and the McCoys actually had one of their fabled shootouts on The Mighty Haag Show grounds.\ In the fall, after the large circuses would close down, many of their biggest acts would come south to pick up six or eight weeks of additional work with the Haag Show. Every night, during the long, dark hours, the carved and gilded wagons traveled the back country roads in order to arrive by dawn in the next town. There were no interstate highways and no tandem semi trucks with air horns.\ When they arrived in each town there was a parade. The circus always had twelve cage wagons in the parade plus the huge "Pawnee Bill" bandwagon, which carried a fifteen-piece band under Everette James's capable direction.\ Everette Robert James was born in New Orleans in 1884. As bandmaster of the Mighty Haag Shows, he had created a formidable reputation in the circus world for his prowess both as a cornet and trumpet player and as the leader of its nine-man musical aggregation. The circus maestro sees that the acts and the music are integrated. Early New Orleans musicians Peter Bocage (composer of "I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate") and Charlie Love praised Everette's technical virtuosity. Originally, he had joined the Mighty Haag Shows in 1906 as leader of the circus's #2 band. Six years later, he joined Molly Bailey's Circus as solo cornetist, before returning to the fold with the Haag as band director a year later.\ Tall and thin, with a long face, a prominent nose, large ears, and a high forehead, he made an imposing appearance. He wore hearing aids in both ears as a result of too many years of being a member of bands predominantly made up of brass players and equally loud percussion instruments.\ Maybelle, an attractive and athletic woman, was a trapeze artist and the prima donna of the Mighty Haag Shows. Following the entry march, she sang "Buy a Bale of Cotton" with other performers joining in the chorus. She had also become famous for her "iron jaw" act in which she was suspended from the rigging of the big top with a brace around her teeth, enabling her to perform death-defying spins as well as other acrobatic feats. It was said she could lift 300 pounds with her teeth. The Nassau (Long Island) Daily Record on August 4, 1927, referred to Maybelle as "one of the most daring and reckless circus aerialists, as dainty as a butterfly with her many whims and fancies, dressed in swagger raiment ablaze with color."\ Maybelle Stewart Clark James was born in Flint, Michigan, in 1891. With her first husband, Walter Clark, she had two sons: Walter, Jr., and Lonnie, both of whom died at a young age. In addition, they had two daughters, Bessie and Fay. Fay, who was also an aerialist, traveled with her mother and stepfather in the Mighty Haag Shows.\ Everette James and Maybelle Clark had met and married in the muck and glory of the circus ring, traipsing together over Texas prairies, through feud-infested Kentucky mountains, into Oregonian forests for more than twenty years. Between bottles and changing of diapers, Maybelle swung on her trapeze, played the calliope on parade, did a banjo stunt in the sideshow, rode fancy horses, and performed "sailor perch" acts on a pole.\ It used to be the dream of every American boy to run away and join the circus. It never occurred to Harry James. He was born into one. Young Harry first met his public at the age of eleven days when his parents introduced him to the circus audience. When he was only a year old, he was already exhibiting a musical flair by beating out simple march time on a drum.\ As a toddler, he took to circus life like a poodle takes to a new toy. "Peripatetic" is the best way to describe the way he dashed from one end of the circus tent to the other. He loved watching the clowns and the freaks, learned the ways of the aerialists from his mother and his sister, and was thrilled to ride the horses, camels, and other animals. During this time he developed his lifelong respect for animals and learned to treat them in a kindly manner. But animals notwithstanding, according to Maybelle, Harry practically lived on the bandstand. The musicians regarded him as the band mascot.\ Joe Cabot, the trumpeter and conductor who became extremely close to Harry James in his last years, said that, when he was a very young boy, Harry considered circus owner Ernest Haag his surrogate father. As Cabot remarked, "When Harry was very down, he would talk about his youth in the circus. He never forgot how kind `Uncle Ernie' was to him at a time when he really needed encouragement."\ Everette could be a stern taskmaster and extremely exacting in his criticism of his young son, the budding musician. Years later, Harry James recalled his saying, "Someday you'll thank me for being this way."\ In 1919, the James family moved to the Christy Brothers Circus and Harry began playing a set of trap drums. At three, amazingly, he was given a featured number with the band, performing on a drum almost as big as he was, which proved to be a huge crowd-pleaser. Once, in the middle of his featured number, Maybelle, ever the doting mother, rushed up onto the stage to push back the cluster of curls that had fallen over his forehead and, she felt, affected his vision.\ Most mothers would probably have been reluctant to see their son make the quick change from babyhood to youth, but Maybelle seemed anxious for him to grow up. She fostered his talent and encouraged him to strive for difficult goals. With the constant traveling of the circus, however, Harry's schooling necessarily suffered.\ Joe Cabot pointed out that, according to Harry, Everette encouraged him to learn to play drums first so that he would learn the basics of rhythm, the foundation of all music. He became more and more accomplished as he watched and imitated other circus drummers. He began to develop a style of his own, exhibiting cleverness and originality. At four, he had become a "hot music" drummer and during a three-week-long illness of the band's regular drummer was elevated to playing the trap drums with the Christy Brothers Concert Band. (Coincidentally, at the same time, his future and favorite drummer, Buddy Rich, was touring the world in vaudeville with his parents, billed as "Traps, the Drum Wonder.") With incredible ease, the child prodigy of the drums was able to play two one-hour-and-forty-minute circus programs on a daily basis. A tune called "Down Home Rag" became his featured number.\ The consummate child of the circus then began hanging out with the contortionists. Maybelle immediately saw that her son showed a natural talent in this field, too. She taught him various floor exercises that had helped her to develop strength and flexibility when she performed as a contortionist. By the age of five, he was billed as "The Human Eel."\ When Harry was six years old, he wandered into the "pad room" (the canvas partition that is to the big tent what wings are to a regular stage) and peeked out to watch Maybelle put the trick horses through their stunts. The curly-haired youngster strayed onto the circus track just as the horses were about to come charging by. In the nick of time, Maybelle's pet horse responded to Harry's plight and leaped to the rescue by standing over him until the other horses rushed by, thereby saving him from being trampled to death.\ That same year, Harry was enrolled at St. Anthony's Catholic School in Beaumont, Texas, where the family had settled. Everette James was Catholic, and therefore his young son was baptized as a Catholic a year later. When he was seven, the Jameses, ever on the move, left Beaumont to join Honest Bill's Circus in Oklahoma for about a year\ By the time the James family moved on to the Lee Brothers Circus, Harry did his contortionist act there as well. He joined with "Dad" Witlark, a seventy-year-old contortionist, who taught him a few of that boneless trade's simpler tricks—such as backbends, retrieving handkerchiefs in his teeth, how to tie himself into pretzel knots—and put him into the act. Dad was starting to become a bit old for this work, but he was still able to bend over backwards, put his face between his ankles, and see how his heels were wearing. Along with the young Harry, the two were billed as "The Oldest And The Youngest Contortionists In The World."\ In one stunt, Harry would place a lighted candle on his head and then draw a hoop over his entire body without knocking over the flame. Another trick called for young James to leap through a flaming hoop. "The World's Youngest Contortionist" also took part in "the spec," circus lingo for the spectacular, wearing a bouffant dress and curls as he sat in a giant slipper dressed as Cinderella. At one performance, the act preceding the contortionists was mostly composed of animals, and someone forgot to close the chute leading to the lions' cage. Out of the corner of his eye, Harry could see the lions emerging from the chute, but in perfect circus tradition he carried on with the show. Luckily, Captain Terrell Jacobs, the animal trainer for the Christy Brothers Circus, realized what was happening. He dashed to the chute, cracked his whip, which stunned the beasts, and, just in time, slammed the door in the lions' muzzles. Because of young Harry's handling of the situation, no one in the audience realized how close they had come to being victims of a rampaging lion.\ Preceding the Jazz Age of the middle and late 1920s, the circus had little if any competition as the focal point of family entertainment. Children of all ages awaited with great anticipation the coming of the circus to town. The spectacle of various daring "live" performances, the high-wire acts, the terrifying yet fascinating animals, the sideshows, the midway, the popcorn and cotton candy, and indeed the stirring march tempo of the circus band exhilarated one and all.\ The most flamboyant circus performers, through years of touring, became as celebrated in their own way as today's rock stars. Master Harry Haag James was learning to become an all-around performer. Unfortunately, a mastoid condition, which led to an operation at the children's hospital, prevented him from continuing as a contortionist.\ In 1927, the James family returned to the Christy Brothers Circus, by this time one of the best-known touring circuses in the country. The twenty-five-wagon, seventy-foot steel-car show toured by train all over America, Canada, and Mexico in the summer and wintered in Beaumont, clocking 19,000 miles a year. Among other attractions, it featured everything from baby African lions right up to a troupe of mammoth elephants, as well as horses, dogs, hens, goats, reindeer, even kangaroos. Along with the most elite performers of one stripe or another was Maybelle James, who was featured as "the most daring and reckless" horse rider racing around the ring straddling two horses. The almost unprecedented five-ring circus kept the eye so busy it was impossible to take it all in.\ Veteran circus trumpeter Jimmy Ille contends that it was trumpeter "Skinny" Goe (pronounced "Go"), not Harry's father, who first put a cornet in eight-year-old Harry's hands. As Ille explains, "Before the show, the band sits behind the center ring. The Christy Brothers Band probably totalled about twenty-five musicians. The guys are up, and they're just barely blowing their horns because you have to save it all for the show. Skinny sits there in the trumpet section and says to little Harry, `Blow this,' and that's how he started playing." In the years ahead, Skinny went on to have a formidable career leading various circus bands.\ Skinny began to secretly teach the little cornetist the rudiments of the instrument outside the flaps of the big top. One day, Everette came upon the two of them together and was amazed at the ability of his young son to play the cornet—so much so that he started teaching him to play the peck horn, an E-flat alto horn. The vowels were written down for him.\ By the age of nine, Harry had switched from drums to trumpet, and at eleven he was playing fourth chair in the Christy Brothers Band. He proudly wore the band's red uniform, complete with gold braid. Rapidly improving his abilities as a soloist, he soon became the first cornetist in the band.\ Harry described his first experience leading a circus band: "My father went over to see his sister, who was a member of the Flying Wards, a flying trapeze act that was playing about forty miles away, and he didn't return in time for the concert. So I just went out and directed the band for the first couple of tunes. Mr. Christy was standing in the back, and my father came running in real quick—he wanted to hurry up and go out there. Mr. Christy said, `Mr. James, Sr., we don't need you for awhile. Your boy's doing quite well.' I directed the entire concert."\ In 1928, Everette gave him the opportunity to take over the leadership of the circus's #2 band. Harry was only twelve years old. This time he wore a blue uniform with gold trim. His band played opposite his father's band under the Christy Brothers big top. This also allowed him to play hot trumpet solos behind "Bessie the Beautiful High Wire Queen," among other acts. According to an article in Billboard, he was now the youngest circus bandleader in the world.\ His father was dead-set against Harry's ever becoming a professional musician because of the constant traveling and inherent insecurities of the business. Everette instead wanted his son to become a doctor or lawyer. Yet he never insisted on Harry's completing his education. When pressed, the dignified and soft-spoken bandmaster had to admit that Harry was talented enough to make a living as a legitimate brass player.\ \ \ O. A. "Red" Gilson, Jack Bell (who claims he helped Harry develop his cornet technique), Jack Carroll, and Skinny Goe were all brass players in the Christy Brothers Circus Band under Everette's direction and witnessed Harry's rapid musical development. Gilson left the Christy Brothers Circus to become leader of the Robbins Brothers Circus Band. His admiration for Harry is shown by the fact that on the sheet music of his composition, "Robbins Brothers Triumphal March," which he wrote in 1928, is inscribed "Dedicated to Harry James." Jimmy Ille relates that this march is not dissimilar to the famous "Ringling Brothers Entry March."\ The two Christy Brothers bands, conducted by the two Jameses, would parade up and down the main street of each city the circus visited, doubling back on their tracks. It got to be a family joke; Harry's band would invariably start playing as Everette's band approached, often causing a comical explosion of mixed marches. Finally, they worked it out so that the #1 band would finally march by the #2 band in respectful silence.\ During these years with the Christy Brothers Band, Everette made use of a substantial number of band arrangements of W. C. Handy's compositions, such as "Memphis Blues" and "St. Louis Blues." And so, while developing his own trumpet style before he was even a teenager, Harry was already learning to play the blues and jazz based on the works of the revered composer known as "The Father of the Blues." It is therefore no great surprise that in later years two of his most respected trumpet solos were on these two blues classics. Everette's band also played arrangements of other contemporary jazz tunes, such as "Tiger Rag," "Milenberg Joys," and "Wolverine Blues."\ The repertoire of Everette James's band consisted of an abundance of marches—"Semper Fidelis," "North Wind," "Thunder and Blazes," and the inevitable "Stars and Stripes Forever." Uan Rasey, who was a trumpeter in the James band during the mid-1940s, and later recorded with the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus Band, remarked: "Marches are the hardest thing. There's no rest, you gotta keep playing from one number to the next. You have to be very exact. That's where Harry developed his endurance."\ Watching his father's every move on the bandstand obviously made a deep impression on the youngster. Jimmy Ille observed that "when Everette played the trumpet, the way he carried that horn, the way the horn stuck out in front of his body, and the way he stood in front of the band, years later you'd look and say, `Harry James looks just like his father.'"\ Harry always marveled at his father's ability to play both cornet and trumpet. Merle Evans, the bandmaster of the legendary Ringling Brothers Circus ("Big Bertha," as show folks called it) from 1919 to 1969, and Everette, leading the Christy Brothers Circus Band, on occasion would lead simultaneous parades followed by band concerts. As a youngster, Harry remembered with pride when he was allowed to sit on Merle's lap. Years later, Everette dueled with Evans, who was also considered the foremost cornetist of his time. "Dad said, `I'm going to play so high the piccolo is going to be playing the bass part.'"\ The constant traveling that James endured with his parents and sister in these circus bands formed the pattern for his own musical career. Also, from that time forward, anyone who heard the readily identifiable trumpet sound of Harry James couldn't help noticing that the influence the circus had on him was forever implanted in his playing.\ His years in circus music, playing almost every tune at a full gallop, had developed a set of iron chops that was to hold him in good stead almost to the very end of his life, certainly well past the time when most trumpet players "lose their lip." In addition, Everette's years of stressing the basic fundamentals of trumpet playing and his strict discipline had given Harry a firm foundation that few, if any, of his peers possessed. And, as Harry himself often said, his dad was not loathe to using a switch on his butt to achieve what he wanted.\ Harry James's embouchure was perfect. As several musicians remarked, "I never once saw Harry with a ring around his lip"—the telltale sign of a trumpet player who was not playing his horn "correctly." In these pre-teen and early teenage years, the young trumpeter would spend from two to six hours a day practicing and running over scales as well as passages in the Arban Book, the exercise bible for all young would-be trumpeters.\ When he was only in the seventh grade at Dick Dowling Junior High School in Beaumont, Harry was asked to become a member of the Beaumont High School Band. Oddly enough, this was the first complete year he had ever been in school from the very first day to the end of the school year, for he had been traveling with the circus from April to December the preceding four years.\ At Dick Dowling, he made many friends, partly due to his growing popularity as a musician. Besides that, his classmates were attracted by the colorful life he had led.\ Drew Page, who was later to be a member of the saxophone section in the first James band, recalled (in his highly underrated book, Drew's Blues: A Sideman's Life in the Big Bands) having seen Harry play in 1929 (at the age of thirteen) at the only jazz club in Beaumont as a member of trumpeter Vic Insirilo's group. Drew was curious to encounter such a young boy playing with experienced professionals. Drew remembered, "His style of playing reminded me of [Bix] Beiderbecke's."\ During these years, Harry James developed an all-consuming passion for baseball, as so many youngsters did at that time. This love of baseball would stay with him all his life. For Everette James, however, baseball always had to take second place to practicing the trumpet.\ As James reminisced on a Merv Griffin Show that aired on November 15, 1977: "Dad would say to me, `Here's the Arban Book ... here's two pages and a half; play that. When you get through, call me in.' I'd practice like crazy and call him in.... He'd say, `This wasn't right, that wasn't right.' He didn't care whether it was ten minutes or two hours, but when I played those exercises correctly, then he'd say, `Okay, go play ball' ... which was a beautiful way because if a person is studying music, and they say, `Okay, you've got two hours to practice' ... and they keep looking at the clock: `How much time do I have left?' This way I was on my own."\ Invariably, Harry would cave in to his father's wishes, but the truth was he had two loves: the trumpet and baseball. Despite the hardship he flit he endured at the time, Harry always conceded, "Whatever success I may have had was due to my father sitting me down and really making me practice and practice and practice."\ The Arban Book contained the composition "Carnival of Venice," which all young trumpeters learn to play at one time or another. Harry also learned the more advanced version that the brilliant cornetist Herbert L. Clark, a contemporary of Everette's, had created. Later, Harry used Clark's version of "Carnival of Venice" as the basis for one of his most successful hit records, but in his recorded version he added even further embellishments to the classic piece. Harry met Clark while Clark was touring with his own large band in the Southwest. His respect for Clark's astounding technique also had undeniable influence in the way he interpreted the "Cantabile" section of "Trumpet Blues" as well as "Flight of the Bumble Bee."\ In his last years traveling with the Christy Brothers Circus, Harry James was introduced to alcohol and sex. He admitted to one musician that he started drinking when he was fourteen years old. This was not unusual for circus performers. Girls in the audience were considered easy prey. From their vantage point on the bandstand, musicians could pick out eager young girls to seduce, a ritual that would invariably begin with a few drinks after the show. It was all in a night's work. It later became an integral part of Harry's lifestyle when he began touring with dance orchestras.\ By 1930, the entire nation was in the grip of The Great Depression. Conditions in the circus world were no better than in any other business. Admissions, even for circuses as important as the Christy Brothers, had sunk to twenty-five cents for children and fifty cents for adults. President Herbert Hoover assured his agonized countrymen that things would get better soon, but instead they grew steadily worse. As a result, Everette became a victim of the sliding economy and lost his job with the Christy Brothers Circus.\ The James family moved back to Beaumont and began living at 2216 Railroad Avenue. Everette James's savior, and that of his family's, turned out to be the wealth of the Spindletop Oil Company, whose nearby spouting oil fields allowed the 58,000 residents of Beaumont to weather the wrath of the Depression. The city, situated on the Natches River, formed a natural turning basin, which made it an important port for transporting oil; it was also accessible to the Gulf of Mexico. This helped provide jobs throughout the area.\ The Island Park Association, composed of employees from the Pennsylvania Shipyards and Petroleum Iron Works Company, whose fortunes benefited from Spindletop Oil, retained Everette as director of its newly organized twenty-four-piece band and orchestra. Fourteen-year-old Harry James came along with his father as its featured cornet soloist. Maybelle, now often referred to as "Mabel," became the leading female performer. It was noted in a Beaumont newspaper that "both Mrs. James and her daughter, Fay Stokes [her newly married name], who was also an aerialist, are receiving requests for engagements at the various fairs in this vicinity for the coming fair season. They are recognized performers."\ In 1933, Maybelle's "iron jaw" act ultimately came to an end as a result of an unfortunate accident during which she was raised too quickly by the circus prop boys and every tooth in her mouth apparently jerked loose. From then on, she was reduced to sitting on an elephant singing "Bluebird" while 100 white doves fluttered about her.\ Shortly thereafter, Everette turned down an offer for the family to join the newly formed Cole Brothers Circus, an amalgamation of the Christy Brothers Circus and the Clyde Beatty Circus. The Cole Brothers had bought it for $200,000—a rather exorbitant price to pay for a circus at that time. He and Mabel, however, had had their fill of the sawdust life after thirty-five and twenty-eight years, respectively. "We're not going back—ever," remarked Everette vehemently. "Wading through the mud for your breakfast three blocks away, living in a Pullman like a monkey, showing in rain, sleet, snow.... No, sir, not us!"\ In addition to their involvement with the Island Park Association, Harry and his father became associated with the local chapter of the American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps. This affiliation enabled Harry to play shortstop for the American Legion Team. (He couldn't play baseball on the school team because he was only in junior high.) A scout for the Detroit Tigers admired the fielding range of the lanky young shortstop as well as his left-handed line-drive hitting. For a time, it looked like Harry might become the property of the Tigers and play with its Beaumont farm team.\ On May 1 and 2, 1931, Harry entered a competition in the Texas Band Teacher's Association's Annual Eastern Division contest, named for the composer Victor Herbert and held in Temple, Texas. Though still only a student at the Dick Dowling Junior High School, he was a regular member of the Beaumont High School Band, which was known as the Royal Purple Band. He won first place in the solo contest for his extraordinary rendition of Herbert L. Clark's difficult composition, "Neptune's Court." A tremendous burst of applause for his performance led to two encores.\ Bill Abel played trombone in the Port Arthur High School Band that also participated in this competition. "I remember it like it was yesterday because it was so outstanding. To hear a kid that young play so excellently, so perfectly, was just earthshaking. There were a lot of good trumpet players in high school, but none of them like that—so completely above every other musician in that whole state concert. He astounded the judges so much that they wanted to give him 100 percent, but they said they never had been able to do that, so they gave him a 98. I knew Harry was really headed for big things."\ (The silver trumpet on which Harry played at the Temple contest is now in the possession of his #1 fan, Dick Maher. It stands in an honored place as the base of a lamp in the "Harry James Room" of Maher's Cerritos, California, home. It is a silverplated King trumpet, Liberty Model, made by H. N. White, Cleveland, Ohio.)\ Although band music was never the craze in Texas that high school football has long been, winning the state trumpet championship in the Depression years was of more than passing significance, especially when one considers that the Beaumont youngster's competitors had been two or three years older. Winning this contest was the seminal event that caused the fifteen-year-old trumpeter to consider becoming a professional musician. Graduation from Dick Dowling Junior High School marked the extent of his formal education.\ He began playing in dance bands around the Beaumont area and for the first time studied theory and harmony. A stint with the local Salvation Army band provided another kind of musical experience. At the same time, he reaffirmed his circus roots by appearing as a guest artist with Merle Evans's Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus Band when the circus appeared in Beaumont.\ Everette continued to be determined that Harry would never become a jazz musician. It was obvious even to Everette, however, that Harry possessed the dazzling technique and incredible stamina that could make him a successful professional trumpet player.\ Years later, Tom Jenkins, the retired president of both Alvin College in Texas and Thomas Nelson College in Virginia, was a trumpet student of Everette's and recalled: "He'd sit there during the lesson holding a baton with a heavy wooden butt at the end. If you happened to miss a fingering ... you'd know it 'cause he'd crack you over the knuckles with the butt end of the baton. Man, I thought my fingers would never mature." Tom defended Everette's radical teaching methods. "When I look back, I realize he was holding a standard up for me to strive for."\ As Jenkins further recalled, "The older guys in Beaumont talked about how they would sneak Harry out at night to play jobs that the old man didn't like. Two of the bands Harry worked for were led by George Pegler and Pat Halpin.\ "What's funny is that Claude Lakey (who later became an important member of Harry's band) used to play at a club outside Beaumont called Bill Borden's," said Jenkins. "The story I heard was that Claude was the giant in those days, and Harry walked in his shadow. Claude played everything. At a jam session Claude would just work his way around the band and play every horn. He would cut the guy who he borrowed the horn from, and, of course, in the process, made everybody mad at him."\ Jack McGee was a bassist with various bands around Beaumont who later helped Everette out by teaching buglers at St. Anthony's. While reminiscing about Harry, he said, "Harry was such a talent he didn't stay long around here—why, he could sightread a trumpet part from 100 feet."\ The Depression wore on, and, despite Everette's new job with the Pennsylvania Shipyards and Petroleum Iron Works Company, he still wasn't earning the kind of money he had pulled in for years as a circus bandmaster. Finally, Harry made an important decision. "Dad," he argued, "I can make it as a musician, and it's about time I helped you and Mom out." Finally, Everette agreed.\ Anson Weeks, who had a dance orchestra of some renown, toured Texas in the early 1930s. At that time, his band included Xavier Cugat on violin and Bob Crosby on vocals, who both would make their mark shortly thereafter as leaders of their own orchestras. During a one-nighter in Port Arthur, a tall, distinguished gentleman approached Weeks after each set asking, "Couldn't my son," who was sitting nearby holding his trumpet, "sit in with your band?" Weeks kept stalling Everette James until the next intermission, hoping he would forget about it and stop pressing the issue. Finally, the bandleader used the bromide that musician union regulations would not permit it. After this final rejection, Everette sternly informed Weeks: "My kid is a darn good trumpet player and you're going to be hearing a lot about him."\ Shortly thereafter, young Harry attended an audition at the Baker Hotel in Dallas held by Lawrence Welk, with his seven-piece band. The gangly James, who weighed in at about 130 and was dressed in shorts, made a trip to the nearby town and approached the maestro on the stand. "You don't happen to be looking for a trumpet player, do you?" he asked. Welk looked down at the youngster and remarked dubiously, "I don't know, son. I'd have to hear you play first. Did you bring your horn?" Harry said that he had. After the band completed its rehearsal, the well-established bandleader listened to the ambitious young trumpeter. Unfortunately, Harry was a little too anxiety-ridden because the audition didn't come off too well. Reportedly, Welk's comment was: "You play too loud for my band. Sorry, I can't make room for you."\ Harry's version was a little different. As he remarked, "He asked me what else I could play and I told him the drums. But that wasn't enough. He wanted guys who could play at least four or five instruments, so I didn't get the job."\ Violinist Joe Gill, whose Phillips Flyers worked out of St. Louis, played a date near Beaumont and held auditions. Again, Harry arrived wearing shorts. At first he was ignored by Gill. After a while the leader reluctantly handed him some sheet music to look over, assuming he wasn't good enough to become a member of his band. The tune turned out to be "St. Louis Blues," the most difficult arrangement in the entire Gill library, but a tune James knew well from circus days.\ Vernon Brown, a trombonist in the band, who was later to be Harry's close friend on the Benny Goodman Band, tried to be of assistance. "Hey, kid, look out for this phrase. It starts on a high D, double forte [very loud]. It's tricky." Ironically, the arranger for the piece was Gordon Jenkins, whose composition, "Goodbye," James was destined to play and solo on at the conclusion of every Benny Goodman performance several years later.\ After he ran down "St. Louis Blues" and a few other numbers, Gill recognized the young man's obvious technique and admired his flashy trumpet style. He immediately hired him. A few days later, despite his lingering opposition to Harry's desire to play with dance bands, Everette drove him down to the location date in Galveston at the Balinese Room to join Joe Gill and his Phillips Flyers.\ This engagement officially launched the career of one of the quintessential trumpet players of the twentieth century. The odyssey was about to begin.

PrefaceAcknowledgments1Everette and Maybelle32Louise and Ben173The Kingdom of Swing314Ciribiribin595You Made Me Love You816Trees, The Legs, and The Lip1057Hollywood Royalty1378The In-Between Years1639Back to Basie19510I Don't Want to Walk Without You239Notes285Bibliography301Index303

\ Steve EddyTrumpet Blues" by veteran PR wizard Peter J. Levinson is a gem....below the surface, there's a fascinating human story....that Levinson, with his vast storehouse of knowledge and sources, has told with grace and verve.\ — The Orange County Register\ \ \ \ \ Terry TeachoutHarry James, like Nat Cole, was a jazz master. If you doubt it, read Triumpet Blues\ — Wall Street Journal\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyAn engrossing, swinging biography of a jazz icon, this book traces the life of Harry James, a trumpeter and bandleader who played in Benny Goodman's Orchestra in the '30s, and who led the country's most popular big band during World War II. Levinson, a jazz publicist who knew James from 1959 until the latter's death in 1983, presents the life of the flashy trumpeter as one of fame, fortune and eventual self-destruction. Born in Georgia in 1916 and raised in Texas, James had an insecure, peripatetic childhood. His mother was a trapeze artist and his father a circus bandleader, and James played in the circus band. Taking Louis Armstrong as his musical role model, James, who was white, was recruited to play in Benny Goodman's band, then left to form his own hugely acclaimed band, marrying film star Betty Grable and acting in movies himself. Over the next two decades, his star waned, but he staged a comeback of sorts in the late '50s, playing in Nevada casinos and continuing fitfully to reinvent his band throughout the next two decades. James's three marriages were ruined by addiction to alcohol, sex and gambling. Grable divorced him in 1965 following a 22-year marriage marked by his constant infidelities, neglect of their two daughters and, according to Levinson, by violent abuse. While many jazz critics dismiss James's romantic bluesy style and wide vibrato as schmaltzy and sentimental, Levinson disagrees. This robust biography offers a heady plunge into the swing era and a vivid portrait of a daring and inventive artist. Photos. (Oct.) FYI: A companion CD from Capitol Jazz, annotated by Levinson, features 16 of James's hit songs. Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsLeading jazz publicist Levinson makes his literary debut with this biography of the late bandleader, who in the '30s and '40s established himself as a rival to Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey, among others. James's early years were particularly formative, as he was born to parents who devoted much of their lives to performing for the circus. "Young Harry first met his public at the age of 11 days, when his parents introduced him to the circus audience," Levinson writes. With his look at the life of circus entertainers in the early part of the century, Levinson hooks the reader immediately. He makes James's progression from childhood circus performer to budding musician at age 12— when he was "the youngest circus bandleader in the world"—a seamless evolution. By the early 1930s, when James was struggling to succeed as a trumpet player, the reader has a strong sense of his musical growth. It wasn't until December 1936, when Goodman—who would stay friends with James throughout their lifetimes, despite their competition for bookings—invited him to join his band, that the trumpeter became a star. Levinson captures the era well, citing the impact of WWII on popular music, telling stories of the biggest stars of the time (including Goodman, Dorsey, James's hero Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, and Frank Sinatra, whom James helped discover by giving the "kid" his first recording gig) and the bigotry integrated big bands faced on the road. To his credit, Levinson, while hardly ignoring James's legendary womanizing, gambling, and drinking, as well as his lengthy marriage to pinup queen Betty Grable—ultimately victimized by all of James's vices—avoids turning thebandleader's life into a melodramatic soap opera. Instead, he concentrates on the music. Impressive, and a fascinating read not only for fans of jazz, but for students of 20th-century history, Hollywood, and the music business.\ \