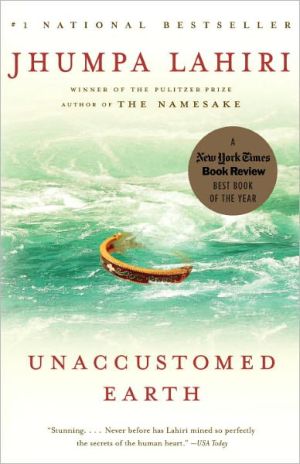

Unaccustomed Earth

From the internationally best-selling, Pulitzer Prize–winning author, a superbly crafted new work of fiction: eight stories—longer and more emotionally complex than any she has yet written—that take us from Cambridge and Seattle to India and Thailand as they enter the lives of sisters and brothers, fathers and mothers, daughters and sons, friends and lovers.\ In the stunning title story, Ruma, a young mother in a new city, is visited by her father, who carefully tends the earth of her garden,...

Search in google:

These eight stories by beloved and bestselling author Jhumpa Lahiri take us from Cambridge and Seattle to India and Thailand, as they explore the secrets at the heart of family life. Here they enter the worlds of sisters and brothers, fathers and mothers, daughters and sons, friends and lovers. Rich with the signature gifts that have established Jhumpa Lahiri as one of our most essential writers, Unaccustomed Earth exquisitely renders the most intricate workings of the heart and mind.The Barnes & Noble ReviewJhumpa Lahiri is a writer who knows her strengths. In her Pulitzer Prize–winning story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, her novel The Namesake, and this collection, Unaccustomed Earth, she has taken what would seem a narrow slice of the immigrant narrative and sent it sprawling. The characters that populate Lahiri's fiction tend to be of a type; more often than not, they are second-generation Indian immigrants, the children of middle-class Bengalis striving to remake themselves as middle-class Americans. Unaccustomed Earth is, in this sense, not a departure. Its eight stories find Lahiri retreading this familiar ground yet also staking out new territory -- the difficult landscape of American adulthood.

Unaccustomed Earth\ After her mother’s death, Ruma’s father retired from the pharmaceutical company where he had worked for many decades and began traveling in Europe, a continent he’d never seen. In the past year he had visited France, Holland, and most recently Italy. They were package tours, traveling in the company of strangers, riding by bus through the countryside, each meal and museum and hotel prearranged. He was gone for two, three, sometimes four weeks at a time. When he was away Ruma did not hear from him. Each time, she kept the printout of his flight information behind a magnet on the door of the refrigerator, and on the days he was scheduled to fly she watched the news, to make sure there hadn’t been a plane crash anywhere in the world.\ Occasionally a postcard would arrive in Seattle, where Ruma and Adam and their son Akash lived. The postcards showed the facades of churches, stone fountains, crowded piazzas, terra-cotta rooftops mellowed by late afternoon sun. Nearly fifteen years had passed since Ruma’s only European adventure, a month-long EuroRail holiday she’d taken with two girlfriends after college, with money saved up from her salary as a para- legal. She’d slept in shabby pensions, practicing a frugality that was foreign to her at this stage of her life, buying nothing but variations of the same postcards her father sent now. Her father wrote succinct, impersonal accounts of the things he had seen and done: “Yesterday the Uffizi Gallery. Today a walk to the other side of the Arno. A trip to Siena scheduled tomorrow.” Occasionally there was a sentence about the weather. But there was never a sense of her father’s presence in those places. Ruma was reminded of the telegrams her parents used to send to their relatives long ago, after visiting Calcutta and safely arriving back in Pennsylvania.\ The postcards were the first pieces of mail Ruma had received from her father. In her thirty-eight years he’d never had any reason to write to her. It was a one-sided correspondence; his trips were brief enough so that there was no time for Ruma to write back, and besides, he was not in a position to receive mail on his end. Her father’s penmanship was small, precise, slightly feminine; her mother’s had been a jumble of capital and lowercase, as though she’d learned to make only one version of each letter. The cards were addressed to Ruma; her father never included Adam’s name, or mentioned Akash. It was only in his closing that he acknowledged any personal connection between them. “Be happy, love Baba,” he signed them, as if the attainment of happiness were as simple as that.\ In August her father would be going away again, to Prague. But first he was coming to spend a week with Ruma and see the house she and Adam had bought on the Eastside of Seattle. They’d moved from Brooklyn in the spring, for Adam’s job. It was her father who suggested the visit, calling Ruma as she was making dinner in her new kitchen, surprising her. After her mother’s death it was Ruma who assumed the duty of speaking to her father every evening, asking how his day had gone. The calls were less frequent now, normally once a week on Sunday afternoons. “You’re always welcome here, Baba,” she’d told her father on the phone. “You know you don’t have to ask.” Her mother would not have asked. “We’re coming to see you in July,” she would have informed Ruma, the plane tickets already in hand. There had been a time in her life when such presumptuousness would have angered Ruma. She missed it now.\ Adam would be away that week, on another business trip. He worked for a hedge fund and since the move had yet to spend two consecutive weeks at home. Tagging along with him wasn’t an option. He never went anywhere interesting—usually towns in the Northwest or Canada where there was nothing special for her and Akash to do. In a few months, Adam assured her, the trips would diminish. He hated stranding Ruma with Akash so often, he said, especially now that she was pregnant again. He encouraged her to hire a babysitter, even a live-in if that would be helpful. But Ruma knew no one in Seattle, and the prospect of finding someone to care for her child in a strange place seemed more daunting than looking after him on her own. It was just a matter of getting through the summer—in September, Akash would start at a preschool. Besides, Ruma wasn’t working and couldn’t justify paying for something she now had the freedom to do.\ In New York, after Akash was born, she’d negotiated a part-time schedule at her law firm, spending Thursdays and Fridays at home in Park Slope, and this had seemed like the perfect balance. The firm had been tolerant at first, but it had not been so easy, dealing with her mother’s death just as an important case was about to go to trial. She had died on the operating table, of heart failure; anesthesia for routine gallstone surgery had triggered anaphylactic shock.\ After the two weeks Ruma received for bereavement, she couldn’t face going back. Overseeing her clients’ futures, preparing their wills and refinancing their mortgages, felt ridiculous to her, and all she wanted was to stay home with Akash, not just Thursdays and Fridays but every day. And then, miraculously, Adam’s new job came through, with a salary generous enough for her to give notice. It was the house that was her work now: leafing through the piles of catalogues that came in the mail, marking them with Post-its, ordering sheets covered with dragons for Akash’s room.\ “Perfect,” Adam said, when Ruma told him about her father’s visit. “He’ll be able to help you out while I’m gone.” But Ruma disagreed. It was her mother who would have been the helpful one, taking over the kitchen, singing songs to Akash and teaching him Bengali nursery rhymes, throwing loads of laundry into the machine. Ruma had never spent a week alone with her father. When her parents visited her in Brooklyn, after Akash was born, her father claimed an armchair in the living room, quietly combing through the Times, occasionally tucking a finger under the baby’s chin but behaving as if he were waiting for the time to pass.\ Her father lived alone now, made his own meals. She could not picture his surroundings when they spoke on the phone. He’d moved into a one-bedroom condominium in a part of Pennsylvania Ruma did not know well. He had pared down his possessions and sold the house where Ruma and her younger brother Romi had spent their childhood, informing them only after he and the buyer went into contract. It hadn’t made a difference to Romi, who’d been living in New Zealand for the past two years, working on the crew of a German documentary filmmaker. Ruma knew that the house, with the rooms her mother had decorated and the bed in which she liked to sit up doing crossword puzzles and the stove on which she’d cooked, was too big for her father now. Still, the news had been shocking, wiping out her mother’s presence just as the surgeon had.\ She knew her father did not need taking care of, and yet this very fact caused her to feel guilty; in India, there would have been no question of his not moving in with her. Her father had never mentioned the possibility, and after her mother’s death it hadn’t been feasible; their old apartment was too small. But in Seattle there were rooms to spare, rooms that stood empty and without purpose.\ Ruma feared that her father would become a responsibility, an added demand, continuously present in a way she was no longer used to. It would mean an end to the family she’d created on her own: herself and Adam and Akash, and the second child that would come in January, conceived just before the move. She couldn’t imagine tending to her father as her mother had, serving the meals her mother used to prepare. Still, not offering him a place in her home made her feel worse. It was a dilemma Adam didn’t understand. Whenever she brought up the issue, he pointed out the obvious, that she already had a small child to care for, another on the way. He reminded her that her father was in good health for his age, content where he was. But he didn’t object to the idea of her father living with them. His willingness was meant kindly, generously, an example of why she loved Adam, and yet it worried her. Did it not make a difference to him? She knew he was trying to help, but at the same time she sensed that his patience was wearing thin. By allowing her to leave her job, splurging on a beautiful house, agreeing to having a second baby, Adam was doing everything in his power to make Ruma happy. But nothing was making her happy; recently, in the course of conversation, he’d pointed that out, too.\ How freeing it was, these days, to travel alone, with only a single suitcase to check. He had never visited the Pacific Northwest, never appreciated the staggering breadth of his adopted land. He had flown across America only once before, the time his wife booked tickets to Calcutta on Royal Thai Airlines, via Los Angeles, rather than traveling east as they normally did. That journey was endless, four seats, he still remembered, among the smokers at the very back of the plane. None of them had the energy to visit any sights in Bangkok during their layover, sleeping instead in the hotel provided by the airline. His wife, who had been most excited to see the Floating Market, slept even through dinner, for he remembered a meal in the hotel with only Romi and Ruma, in a solarium overlooking a garden, tasting the spiciest food he’d ever had in his life as mosquitoes swarmed angrily behind his children’s faces. No matter how they went, those trips to India were always epic, and he still recalled the anxiety they provoked in him, having to pack so much luggage and getting it all to the airport, keeping documents in order and ferrying his family safely so many thousands of miles. But his wife had lived for these journeys, and until both his parents died, a part of him lived for them, too. And so they’d gone in spite of the expense, in spite of the sadness and shame he felt each time he returned to Calcutta, in spite of the fact that the older his children grew, the less they wanted to go.

\ Michiko KakutaniAs she did in her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection of stories Interpreter of Maladies (1999) and her dazzling 2003 novel The Namesake, Ms. Lahiri writes about these people in Unaccustomed Earth with an intimate knowledge of their conflicted hearts, using her lapidary eye for detail to conjure their daily lives with extraordinary precision: the faint taste of coconut in the Nice cookies that a man associates with his dead wife; the Wonder Bread sandwiches, tinted green with curry, that a Bengali mother makes for her embarrassed daughter to take to school. A Chekhovian sense of loss blows through these new stories: a reminder of Ms. Lahiri's appreciation of the wages of time and mortality and her understanding too of the missed connections that plague her husbands and wives, parents and children, lovers and friends.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Liesl Schillinger…the fact that America is still a place where the rest of the world comes to reinvent itself—accepting with excitement and anxiety the necessity of leaving behind the constrictions and comforts of distant customs—is the underlying theme of Jhumpa Lahiri's sensitive new collection of stories…Lahiri handles her characters without leaving any fingerprints. She allows them to grow as if unguided, as if she were accompanying them rather than training them through the espalier of her narration. Reading her stories is like watching time-lapse nature videos of different plants, each with its own inherent growth cycle, breaking through the soil, spreading into bloom or collapsing back to earth.\ —The New York Times Book Review\ \ \ Lily TuckThe eight stories in this collection revolve less around the dislocation Lahiri's earlier Bengali characters encountered in America and more around the assimilation experienced by their children—children who, while conscious of and self-conscious about their parents' old-world habits, vigorously reject them in favor of American lifestyles and partners. Lahiri, who was raised and educated in the United States and whose parents are Bengali, is adept at showing us these cultural and generational conflicts. The stories she generates from these clashes appear true to life, and while a few lack nuance and at times feel familiar, they are never predictable. Lahiri is far too accomplished and empathic a writer to relax her gaze; she excels at uncovering character and choosing detail.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe gulf that separates expatriate Bengali parents from their American-raised children-and that separates the children from India-remains Lahiri's subject for this follow-up to Interpreter of Maladiesand The Namesake. In this set of eight stories, the results are again stunning. In the title story, Brooklyn-to-Seattle transplant Ruma frets about a presumed obligation to bring her widower father into her home, a stressful decision taken out of her hands by his unexpected independence. The alcoholism of Rahul is described by his elder sister, Sudha; her disappointment and bewilderment pack a particularly powerful punch. And in the loosely linked trio of stories closing the collection, the lives of Hema and Kaushik intersect over the years, first in 1974 when she is six and he is nine; then a few years later when, at 13, she swoons at the now-handsome 16-year-old teen's reappearance; and again in Italy, when she is a 37-year-old academic about to enter an arranged marriage, and he is a 40-year-old photojournalist. An inchoate grief for mothers lost at different stages of life enters many tales and, as the book progresses, takes on enormous resonance. Lahiri's stories of exile, identity, disappointment and maturation evince a spare and subtle mastery that has few contemporary equals. (Apr.)\ Copyright 2007Reed Business Information\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalFour years after the release of her best-selling novel, The Namesake , the Pulitzer Prize-winning Lahiri returns with her highly anticipated second collection of short stories exploring the inevitable tension brought on by family life. The title story, for example, takes on a young mother nervously hosting her widowed father, who is visiting between trips he takes with a lover he has kept secret from his family. What could have easily been a melodramatic soap opera is instead a meticulously crafted piece that accurately depicts the intricacies of the father-daughter relationship. In a departure from her first book of short stories, Interpreter of Maladies , Lahiri divides this book into two parts, devoting the second half of the book to "Hema and Kaushik," three stories that together tell the story of a young man and woman who meet as children and, by chance, reunite years later halfway around the world. The author's ability to flesh out completely even minor characters in every story, and especially in this trio of stories, is what will keep readers invested in the work until its heartbreaking conclusion. Recommended for all public libraries. [See Prepub Alert, LJ 12/07.]-Sybil Kollappallil, Library Journal\ Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalAll eight of the longish stories in Lahiri's third book deal with various male/female relationships-father/daughter, husband/wife, brother/sister, roommates, step-family, childhood friends-in the context of the immigrant experience. Specifically, Lahiri examines the gulf between first- and second-generation Bengali immigrants-the expectations, often unmet, about, for instance, dress, achievement, and marriage. Lahiri's strengths are her characterizations and knack for universalizing the particular. The last three stories feature characters who meet as children, when Hema's parents share their house with Kaushik's family. Kaushik finds himself sharing more than just his house when, after his mother's death (a recurring theme), his father remarries a woman with two younger daughters. Sarita Choudhury and Ajay Naidu alternate reading the female and male voices, with accents waxing and waning as the story demands. Lahiri won a Pulitzer Prize for her 1999 collection The Namesake. Unaccustomed Earth earned a front-page review in the New York Times Book Review and debuted at the top of the best sellers list, making it a no-brainer for all library collections.\ —John Hiett\ \ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsLahiri (The Namesake, 2003, etc.) extends her mastery of the short-story format in a collection that has a novel's thematic cohesion, narrative momentum and depth of character. The London-born, American-raised author of Indian descent returns with some of her most compelling fiction to date. Each of these eight stories, most on the longish side, a few previously published in magazines, concerns the assimilation of Bengali characters into American society. The parents feel a tension between the culture they've left behind (though to which they frequently return) and the adopted homeland where they always feel at least a little foreign. Their offspring, who are generally the protagonists of these stories, are typically more Americanized, adopting a value system that would scandalize their parents, who are usually oblivious to the college lives their sons and daughters lead. Ambition and accomplishment are givens in these families, where it's understood that nothing less than attending a top-flight school and entering an honored profession (medicine, law, academics) will satisfy. The stunning title story presents something of a role reversal, as a Bengali daughter and her American husband must come to terms with the secrets harbored by her father. The story expresses as much about love, loss and the family ties that stretch across continents and generations through what it doesn't say, and through what is left unaddressed by the characters. Even "Only Goodness," the most heavy-handed piece in the collection, which concerns a character's guilt over her brother's alcoholism, sustains the reader's interest until the last page. The final three stories trace the lives of two characters, Hema andKaushik, from their teen years through their 30s, when fate (or chance) reunites them. An eye for detail, ear for dialogue and command of family dynamics distinguish this uncommonly rich collection. Agent: Eric Simonoff/Janklow & Nesbit\ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewJhumpa Lahiri is a writer who knows her strengths. In her Pulitzer Prizewinning story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, her novel The Namesake, and this collection, Unaccustomed Earth, she has taken what would seem a narrow slice of the immigrant narrative and sent it sprawling. The characters that populate Lahiri's fiction tend to be of a type; more often than not, they are second-generation Indian immigrants, the children of middle-class Bengalis striving to remake themselves as middle-class Americans. Unaccustomed Earth is, in this sense, not a departure. Its eight stories find Lahiri retreading this familiar ground yet also staking out new territory -- the difficult landscape of American adulthood. \ Lahiri's particular brand of prose, at once rich in detail and strikingly economical, plays best to the formal requirements of the short story. The Namesake, while impressive for a first novel, has a meandering quality, as if its author were unsure of how to maintain the momentum of her characters' lives over a full spread of pages. Her stories, by contrast, are commanding; Lahiri knows how to exploit the seemingly infinite resonance of a well-chosen image carefully placed. In the story "Hell-Heaven," the crushing collapse of a platonic romance happens, as it were, offstage. The narrator, a young Bengali girl who watches her mother fall in love with a family friend, remarks the following when he asks her parents for their approval of his chosen bride, a white woman: "My mother nodded her assent, but the following day I saw the teacup Pranab Kaku had used all this time as an ashtray in the kitchen garbage can, in pieces, and three Band-Aids taped to my mother's hand." This teacup, which had earlier signaled Pranab Kaku's assimilation into the family, comes back to quietly mark its fracturing.\ "Hell-Heaven" is just one instance of how Lahiri, with Unaccustomed Earth, has harnessed her talent for the elegiac. Her stories are threaded together by a current of loss -- of lovers, of parents, of home. In particular, the three interlinked stories that finish the collection draw the atmospherics of absence to the fore. Hema and Kaushik, the title characters of this trilogy, move into and out of each other's lives, their presences lingering long after they have parted ways. Lahiri's interest in the elegy is more than a passing mood, and in these three stories she invokes its tradition of direction address quite deliberately. "I had seen you before too many times to count, but a farewell that my family threw for yours, at our house in Inman Square, is when I begin to recall your presence in my life," Hema opens the story "Once in a Lifetime." That a separation and a beginning are inextricable becomes a reality neither Hema nor Kaushik will ever quite shake. Just as the death of his mother and his father's remarriage launch Kaushik into an itinerant adulthood, so too the end of an affair becomes the hinge that forces Hema to begin anew.\ As in the case of the teacup, there are no histrionics. Lahiri's narratives tend to be situational rather than specifically plot driven, the tension more likely to emerge from the wordless spaces between people than from any singular event. The stories of Unaccustomed Earth are, on average, considerably longer than those of Interpreter of Maladies, and Lahiri seems to find her ideal rhythm in the structural liberties of the long short story. She avoids both explicit dramatic pivots and the sagging weight of a full back-story -- the essential details must make their own case. It is when she tries to build her stories from a more conspicuous premise that she falters. "Only Goodness," the collection's single weak link, finds Lahiri falling into the trap of exposition. The very skeleton of the story feels didactic -- the perfect immigrant child reeling in guilt over her younger brother's alcoholism. "I can't fix him. I can't fix what's wrong with this family," Sudha proclaims, the dialogue unable to resist the tropes of teenage melodrama.\ More often, in these rare instances that Lahiri allows her stories to explode, they do so with all the force gathered over their restrained build-up. In "Nobody's Business," another standout, a graduate student's brooding fixation with his female roommate, Sang, finally bursts into a physical confrontation with her unfaithful boyfriend: "It was easy for Paul to pin Farouk to the ground, to dig his fingers into his shoulders. Paul squeezed them tightly, through the thick wool of the sweater, feeling the give of the tendons, aware that Farouk was no longer resisting. For a moment, Paul lay on top of him fully, subduing him like a lover," Lahiri writes. This is her genius -- she waits patiently for her stories to run their natural course. Here, all of Paul's longing for Sang, all of his loneliness and sexual desperation, find unlikely release in a violent, almost sensual encounter with her boyfriend.\ Like so many of the characters in Unaccustomed Earth, Paul exists in the grips of stasis. Where Lahiri's earlier stories dwelt, more often than not, on men and women starting out in the world, her new work turns its attention to people slightly further along in life, catching them at the moment where their lives -- romantic, professional, emotional -- are beginning to plateau. Most affectingly, the title story finds Ruma, a 30-something woman who has left her job at a law firm to raise her young son, adjusting to life in a new city and mourning the death of her mother: "By allowing her to leave her job, splurging on a beautiful house, agreeing to have a second baby, [her husband] was doing everything in his power to make Ruma happy. But nothing was making her happy; recently, in the course of conversation, he'd pointed that out, too." The story is an artist's rendering of a case study in depression. Similarly Amit, in "A Choice of Accommodations," has somehow found himself carrying out the unremitting patterns of domesticity alone, raising his two daughters while his wife toils under the medical resident's inhuman schedule.\ If this sounds dismal, it isn't. Unaccustomed Earth may dwell in the experiences of paralysis and loss, but Lahiri's prose also lends itself to the rhythms of awakening. Her broken, multi-clausal sentences catch her subjects in the throes of realization. For instance, here is Ruma, blaming her husband for the fact that both his parents are still alive: "It was wrong of her, she knew, and yet an awareness had set in, that she and Adam were separate people leading separate lives." Through Ruma, Lahiri has given voice to the sentiment -- neither positive or negative, simply true -- that cements her collection. Perhaps, in the end, these stories are not sadder, only wiser. --Amelia Atlas\ Amelia Atlas's reviews have appeared in the New York Sun, 02138, and the Harvard Book Review.\ \ \