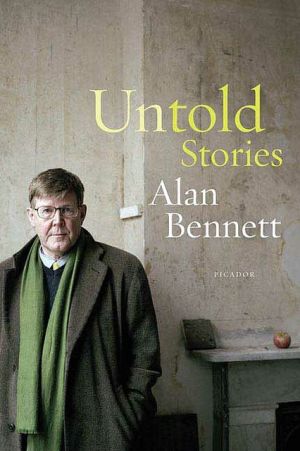

Untold Stories

An instant bestseller in the U.K., Untold Stories brings together the finest and funniest writing by one of England's best-known literary figures. In his first major collection since Writing Home, Alan Bennett opens with a poignant memoir of growing up in Leeds and closes with an account of his cancer diagnosis and recovery, with everything from his much-celebrated essays to his irreverent comic pieces and reviews in between.

Search in google:

An instant bestseller in the U.K., Untold Stories brings together the finest and funniest writing by one of England's best-known literary figures. In his first major collection since Writing Home, Alan Bennett opens with a poignant memoir of growing up in Leeds and closes with an account of his cancer diagnosis and recovery, with everything from his much-celebrated essays to his irreverent comic pieces and reviews in between.The Washington Post - Michael Dirda"At the drabber moments of my life (swilling some excrement from the steps, for instance, or rooting with a bent coat-hanger down a blocked sink) thoughts occur like 'I bet Tom Stoppard doesn't have to do this' or 'There is no doubt David Hare would have deputed this to an underling.' " There you have the glory of Alan Bennett: You don't have to be a famous playwright to know just how he feels.

Untold Stories\ \ By ALAN BENNETT \ FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX\ Copyright © 2005 Alan Bennett\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0-374-28103-3 \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ There is a wood, the canal, the river, and above the river the railway and the road. It's the first proper country that you get to as you come north out of Leeds, and going home on the train I pass the place quite often. Only these days I look. I've been passing the place for years without looking because I didn't know it was a place; that anything had happened there to make it a place, let alone a place that had something to do with me. Below the wood the water is deep and dark and sometimes there's a boy fishing or a couple walking a dog. I suppose it's a beauty spot now. It probably was then. \ 'Has there been any other mental illness in your family?' Mr Parr's pen hovers over the Yes/No box on the form and my father, who is letting me answer the questions, looks down at his trilby and says nothing.\ 'No,' I say confidently, and Dad turns the trilby in his hands.\ 'Anyway,' says Mr Parr kindly but with what the three of us know is more tact than truth, 'depression isn't really mental illness. I see it all the time.' Mr Parr sees it all the time because he is the Mental Health Welfare Officer for the Craven district, and late this September evening in 1966 Dad and I are sitting in his bare linoleum-floored office above Settle police station while he takes a history of mymother.\ 'So there's never been anything like this before?' 'No,' I say, and without doubt or hesitation. After all, I'm the educated one in the family. I've been to Oxford. If there had been 'anything like this' I should have known about it. 'No, there's never been anything like this.' 'Well,' Dad says, and the information is meant for me as much as for Mr Parr, 'she did have something once. Just before we were married.' And he looks at me apologetically. 'Only it was nerves more. It wasn't like this.' The 'this' that it wasn't like was a change in my mother's personality that had come about with startling suddenness. Over a matter of weeks she had lost all her fun and vitality, turning fretful and apprehensive and inaccessible to reason or reassurance. As the days passed the mood deepened, bringing with it fantasy and delusion; the house was watched, my father made to speak in a whisper because there was someone on the landing, and the lavatory (always central to Mam's scheme of things) was being monitored every time it was flushed. She started to sleep with her handbag under her pillow as if she were in a strange and dangerous hotel, and finally one night she fled the house in her nightgown, and Dad found her wandering in the street, whence she could only be fetched back into the house after some resistance. Occurring in Leeds, where they had always lived, conduct like this might just have got by unnoticed, but the onset of the depression coincided with my parents' retirement to a village in the Dales, a place so small and close-knit that such bizarre behaviour could not be hidden. Indeed it was partly the knowledge that they were about to leave the relative anonymity of the city for a small community where 'folks knew all your business' and that she would henceforth be socially much more visible than she was used to ('I'm the centrepiece here') that might have brought on the depression in the first place. Or so Mr Parr is saying. My parents had always wanted to be in the country and have a garden. Living in Leeds all his life Dad looked back on the childhood holidays he had spent on a farm at Bielby in the East Riding as a lost paradise. The village they were moving to was very pretty, too pretty for Mam in her depressed mood: 'You'll see,' she said, 'we'll be inundated with folk visiting.'\ The cottage faced onto the village street but had a long garden at the back, and it seemed like the place they had always dreamed of. This was in 1966. A few years later I wrote a television play, Sunset Across the Bay, in which a retired couple not unlike my parents leave Leeds to go and live in Morecambe. As the coach hits the M62, bearing them away to a new life, the wife calls out, 'Bye bye, mucky Leeds!' And so it had seemed. Now Dad was being told that it was this longed-for escape that had brought down this crushing visitation on his wife. Not surprisingly he would not believe it. In their last weeks in Leeds Dad had put Mam's low spirits down to the stress of the impending upheaval. Once the move had been accomplished, though, the depression persisted so now he fell back on the state of the house, blaming its bare unfurnished rooms, still with all the decorating to be done. 'Your Mam'll be better when we've got the place straight,' he said. 'She can't do with it being all upset.' So, while she sat fearfully on a hard chair in the passage, he got down to the decorating. My brother, who had come up from Bristol to help with the move, also thought the state of the house was to blame, fastening particularly on an item that seemed to be top of her list of complaints, the absence of staircarpet. I think I knew then that stair-carpet was only the beginning of it, and indeed when my brother galvanised a local firm into supplying and fitting the carpet in a couple of days Mam seemed scarcely to notice, the clouds did not lift, and in due course my brother went back to Bristol and I to London. Over the next ten years this came to be the pattern. The onset of a bout of depression would fetch us home for a while, but when no immediate recovery was forthcoming we would take ourselves off again while Dad was left to cope. Or to care, as the phrase is nowadays. Dad was the carer. We cared, of course, but we still had lives to lead: Dad was retired - he had all the time in the world to care.\ 'The doctor has put her on tablets,' Dad said over the phone, 'only they don't seem to be doing the trick.' Tablets seldom did, even when one saw what was coming and caught it early. The onset of depression would find her sitting on unaccustomed chairs - the cork stool in the bathroom, the hard chair in the hall that was just there for ornament and where no one ever sat, its only occupant the occasional umbrella. She would perch in the passage, dumb with misery and apprehension, motioning me not to go into the empty living room because there was someone there.\ 'You won't tell anybody?' she whispered.\ 'Tell anybody what?'\ 'Tell them what I've done.'\ 'You haven't done anything.'\ 'But you won't tell them?'\ 'Mam!' I said, exasperated, but she put her hand to my mouth, pointed at the living-room door and then wrote TALKING in wavering letters on a pad, mutely shaking her head. As time went on these futile discussions would become less intimate (less caring even), the topography quite spread out, with the parties not even in adjoining rooms. Dad would be sitting by the living-room fire while Mam hovered tearfully in the doorway of the pantry, the kitchen in between empty.\ 'Come in the pantry, Dad,' she'd call.\ 'What for? What do I want in the pantry?'\ 'They can see you.'\ 'How can they see me? There's nobody here.' 'There is, only you don't know. Come in here.'\ It didn't take much of this before Dad lapsed into a weary silence.\ 'Oh, whish't,' he'd say, 'be quiet.'\ A play could begin like this, I used to think - with a man on stage, sporadically angry with a woman off stage, his bursts of baffled invective gradually subsiding into an obstinate silence. Resistant to the off-stage entreaties, he continues to ignore her until his persistent refusal to respond gradually tempts the woman into view. Or set in the kitchen, the empty room between them, no one on stage at all, just the voices off. And what happens when they do come on stage? Violence, probably. It was all so banal. Missionary for her sunless world, my mother was concerned to convince us in the face of all vehement denial that sooner or later she would be taken away. And of course she was right. Her other fears ... of being spied on, listened to, shamed and detected ... were ordinary stuff too. This was not the territory of grand delusion, her fears not decked out in the showy accoutrements of fashionable neurosis. None of Freud's patients hovered at pantry doors; Freud's selected patients, I always felt, the ordinary not getting past, or even to, the first consultation because too dull, the final disillusion to have fled across the border into unreason only to find you are as mundane mad as you ever were sane. Certainly in all her excursions into unreality Mam remained the shy, unassuming woman she had always been, none of her fantasies extravagant, her claims, however irrational they might be, always modest. She might be ill, disturbed, mad even, but she still knew her place. It may be objected that madness did not come into it; that, as Mr Parr had said, this was depression and a very different thing. But though we clung to this assurance, it was hard not to think these delusions mad and the tenacity with which she held to them, defended them, insisted on them the very essence of unreason. While it was perhaps naïve of us to expect her to recognise she was ill, or that standing stock still on the landing by the hour together was not normal behaviour, it was this determination to convert you to her way of thinking that made her behaviour hardest to bear. 'I wouldn't care,' Dad said, 'but she tries to get me on the same game.' Not perceiving her irrationalities as symptoms, my father had no other remedy than common sense. 'You're imagining stuff,' he would say, flinging wide the wardrobe door. 'Where is he? Show me!' The non-revelation of the phantom intruder ought, it seemed to Dad, to dent Mam's conviction, persuade her that she was mistaken. But not a bit of it. Putting her finger to her lips (the man in the wardrobe now having mysteriously migrated to the bathroom), she drew him to the window to point at the fishman's van, looking at him in fearful certainty, even triumph; he must surely see that the fate she feared, whatever it was, must soon engulf them both. But few nights passed uninterrupted, and Dad would wake to find the place beside him empty, Mam scrabbling at the lock of the outside door or standing by the bedroom window looking out at a car in the car park that she said was watching the house. How he put up with it all I never asked, but it was always this missionary side to her depression, the aggressiveness of her despair and her conviction that hers was the true view of the world that was the breaking point with me and which, if I were alone with her, would fetch me to the brink of violence. I once nearly dragged her out of the house to confront an elderly hiker who was sitting on the wall opposite, eating his sandwiches. He would have been startled to have been required to confirm to a distraught middle-aged man and his weeping mother that his shorts and sandals were not some subtle disguise, that he was not in reality an agent of ... what? Mam never specified. But I would have seemed the mad one and the brute. Once I took her by the shoulders and shook her so hard it must have hurt her, but she scarcely seemed to mind. It just confirmed to her how insane the world had become. 'We used to be such pals,' she'd say to me, shaking her head and refusing to say more because the radio was listening, instead creeping upstairs to the cold bedroom to perch on one of the flimsy bedroom chairs, beckoning me to stay silent and do the same as if this were a satisfactory way to spend the morning. And yet, as the doctor and everybody else kept saying, depression was not madness. It would lift. Light would return. But when? The young, sympathetic doctor from the local practise could not say. The senior partner whom we had at first consulted was a distinguished-looking figure, silver-haired, loud-talking, a Rotarian and pillar of the community. Unsurprisingly he was also a pull your socks up merchant and did not hold with depression. At his happiest going down potholes to assist stricken cavers, he was less adept at getting patients out of their more inaccessible holes. How long such depressions lasted no doctor was prepared to say, nor anyone else that I talked to. There seemed to be no timetable, this want of a timetable almost a definition of the disease. It might be months (the optimistic view), but one of the books I looked into talked about years, though what all the authorities did seem agreed on was that, treated or not, depression cleared up in time. One school of thought held that time was of the essence, and that the depression should be allowed to run its course unalleviated and unaccelerated by drugs. But on my mother drugs seemed to have no effect anyway, and if the depression were to run its course and it did take years, many months even, what would happen to my father? Alone in the house, knowing no one in the village well enough to call on them for help, he was both nurse and gaoler. Coaxing his weeping parody of a wife to eat, with every mouthful a struggle, then smuggling himself out of the house to do some hasty shopping, hoping that she would not come running down the street after him, he spent every day and every fitful night besieged by Mam's persistent assaults on reality, foiling her attempts to switch off the television, turn off the lights or pull the curtains against her imaginary enemies, knowing that if he once let her out of his sight she would be scrabbling at the lock of the front door trying to flee this house which was both her prison and her refuge.\ Thus it was that after six weeks of what Dad called 'this flaming carry-on' it was as much for his sake as for hers that the doctor arranged that she should be voluntarily admitted to the mental hospital in Lancaster. Lancaster Moor Hospital is not a welcoming institution. It was built at the beginning of the nineteenth century as the County Asylum and Workhouse, and seen from the M6 it has always looked to me like a gaunt grey penitentiary. Like Dickens's Coketown, the gaol might have been the infirmary and the infirmary the gaol. It was a relief, therefore, to find the psychiatric wing where Mam was to be admitted not part of the main complex but a villa, Ridge Lee, set in its own grounds, and as we left Mam with a nurse in the entrance hall that September morning it seemed almost cheerful. Dad was not uncheerful too, relieved that now at any rate something was going to be done and that 'she's in professional hands'. Even Mam seemed resigned to it, and though she had never been in hospital in her life she let us kiss her goodbye and leave without protest. It was actually only to be goodbye for a few hours, as visiting times were from seven to eight and though it was a fifty mile round trip from home Dad was insistent that we would return that same evening, his conscientiousness in this first instance setting the pattern for the hundreds of hospital visits he was to make over the next eight years, with never a single one missed and agitated if he was likely to be even five minutes late. I had reached early middle age with next to no experience of mental illness. At Oxford there had been undergraduates who had had nervous breakdowns, though I never quite believed in them and had never visited the Warnford Hospital on the outskirts of the city where they were usually consigned. Later, teaching at Magdalen, I had had a pupil, an irritating, distracted boy who would arrive two hours late for tutorials or ignore them altogether, and when he did turn up with an essay it would be sixty or seventy pages long. When I complained about him in pretty unfeeling terms one of the Fellows took me on one side and explained kindly that he was 'unbalanced', something that had never occurred to me though it was hard to miss. Part of me probably still thought of neurosis as somehow 'put on', a way of making oneself interesting - the reason why when I was younger I thought of myself as slightly neurotic. When I was seventeen I had had a friend a few years older than me who, I realise when I look back, must have been schizophrenic. He had several times gone through the dreadful ordeal of insulin-induced comas that were the fashionable treatment then, but I never asked him about it, partly out of embarrassment but also because I was culpably incurious. Going into the army and then to university, I lost touch with him, and it was only in 1966, on the verge of leaving Leeds, that I learned that he had committed suicide.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ Excerpted from Untold Stories by ALAN BENNETT Copyright ©2005 by Alan Bennett. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Untold stories1Written on the body127Seeing stars157The ginnel174Diaries 1996-2004177The lady in the van367The national theatre383The history boys388Hymn409Cheeky chappies416The last of the sun423Thora Hird436Lindsay Anderson441Going to the pictures453Spoiled for choice477Portrait or bust494Making York Minster515Country arcade, Leeds520A room of my own524Denton Welch532England gone : Philip Larkin538Staring out of the window543A common assault557Arise, sir ...578An average rock bun596

\ From the Publisher"Surprising, funny, and deeply affecting . . . [Alan Bennett] is a prose stylist of disarming grace and sly humor."—The New York Times Book Review "Untold Stories is intelligent, educated, engaging, humane, self-aware, cantankerous, and irresistibly funny. You want it to go on forever."—The Sunday Times (London)\ "Painfully intimate, stoically comic . . . Bennett's deadpan, self-deprecating humor translates perfectly."—David Gates, O, The Oprah Magazine\ "A great achievement and a book of lasting value."—The Guardian (U.K.)\ "A masterpiece of reminiscence. There is probably no other distinguished English man of letters more instantly likable than Bennett."—Michael Dirda, The Washington Post Book World "It is a glaring example of modern English frivolity that [Bennett] is not simply regarded—with awe and terror—as one of the greatest living English writers. . . . If you want to understand the cultural wars in England now, and if you want to come to grips with a great writer and a challenging mind, then Bennett is your man."—The Nation "While he plays the old crank who is put upon by the world as it is, Bennett reveals an eye for detail and a feel for the complexity of human interactions."—Publishers Weekly\ "[Bennett] is a fine storyteller. . . . His memories of fellow actors Peter Cook and Dudly Moore are wry, witty, and honest."—Library Journal\ \ \ \ \ \ Charles McGrathHis book is also preternaturally alert to what Bennett, in discussing his favorite paintings, calls "the glow," by which he means not just light but the small graceful touches, the odd details that catch the corner of the eye — the accidental vantage point, he says, that is also a shortcut to the back of the brain.\ — The New York Times\ \ \ Michael Dirda"At the drabber moments of my life (swilling some excrement from the steps, for instance, or rooting with a bent coat-hanger down a blocked sink) thoughts occur like 'I bet Tom Stoppard doesn't have to do this' or 'There is no doubt David Hare would have deputed this to an underling.' " There you have the glory of Alan Bennett: You don't have to be a famous playwright to know just how he feels.\ — The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyBennett has been known to British audiences of radio, television, stage and screen for decades. In the United States, he's best known as the screenwriter of The Madness of King George and, perhaps, for his experiences with Miss Shepherd, an indigent woman who set up a succession of vans in his front yard for 15 years. Now he returns with a shaggy collection of autobiographical sketches, diary entries, considerations of art, architecture and other authors, as well as an account of his bout with colon cancer. Returning to the precincts of his straitlaced, working-class British background, Bennett reveals a lost world whose influence and mores have trailed him his entire life. He revisits the Leeds that he knew in the 1940s, where he was first exposed to music and theater, and where his parents, both shy and retiring people, set lack of pretension as the highest value. While he plays the old crank who is put upon by the world as it is, Bennett reveals an eye for detail and a feel for the complexity of human interactions. And though he laments at length his own late maturation-physical, sexual and intellectual-and lack of sophistication, he shows himself to have achieved a measure of happiness. B&w photos. (Apr.) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn his first major collection of prose since the 1995 British Book of the Year Award winner Writing Home, celebrated British playwright Bennett recalls his parents' marriage, his mother's battle with depression, and the colorful aunties. Dominant themes include suicide, madness, and the decline of his relatives in old age; lightening the narrative load are punctuations of characteristic British humor. As Bennett, the son of a butcher, captures life in 1940s working-class Leeds, he reveals his skill at witty description, especially in the stories about his mother's sisters, working girls before marrying later in life. The author himself narrates, in a distinctively sad voice underscoring the poignancy of the material. This newly available audio will appeal to fans of Bennett's previous works, particularly Writing Home.—Nancy R. Ives, SUNY at Geneseo\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAn eclectic, entertaining and shelf-bending collection of essays, memoirs, introductions, diaries and commentary from the noted English actor, playwright and art-lover. In his introduction, Bennett (Writing Home, 1995, etc.) alludes to the colon cancer he battled in the late 1990s, and he concludes this massive and moving anthology with an essay about that experience-one of the strongest of many strong pieces. He quips, "Sometimes I felt that more people had seen the inside of my bum than had seen some productions at the National Theatre." This appealing self-deprecation is a hallmark of Bennett's prose, including his opening essay, a long piece about a number of his relatives-but with a sharp focus on the mental deterioration of his mother. Bennett also writes about his first awareness that he was gay (including a touching moment with his father, who asks, "You're not one of them, are you?"). Bennett includes segments from his diary (1996-2004), with comments on the deaths of many of his friends and coevals-among them, John Gielgud, Alec Guinness, John Schlesinger and Alan Bates. He comments, as well, on the death of Princess Di, 9/11, the Iraq War (which he despises). There are a couple of very compelling sections about the plays he's written (for stage, radio, film and television), and some essays about another of his loves-paintings. (In his diary, he chronicles visits to galleries all over the world.) There's also an interesting text of a speech in which he identifies four paintings that ought to hang in every English school. Bennett loves the poetry of Philip Larkin, and that poet's name and words pop up frequently in these pages. Among the best pieces is "Staring Out of theWindow," a brief, lucid essay about writing. Another very strong and troubling essay deals with a physical assault he suffered in 1992. An informed mind and heart, a generous spirit-these are the human qualities that emerge on virtually every page of this splendid collection.\ \