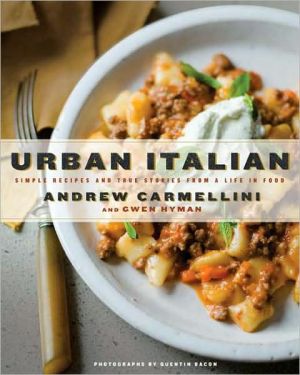

Urban Italian: Simple Recipes and True Stories from a Life in Food

The recipes that one of New York’s best young chefs cooks in his own kitchen: a cookbook full of soulful, sophisticated food and delicious stories\ While waiting for construction to finish on his restaurant A Voce, Andrew Carmellini faced an unusual challenge. After a brilliant career in professional kitchens (including a six-year tour as chef de cuisine at Café Boulud), he was faced with the harsh reality of life as a civilian cook: no prep cooks, no saucier, no daily deliveries—just him and...

Search in google:

The recipes that one of New York’s best young chefs cooks in his own kitchen: a cookbook full of soulful, sophisticated food and delicious storiesWhile waiting for construction to finish on his restaurant A Voce, Andrew Carmellini faced an unusual challenge. After a brilliant career in professional kitchens (including a six-year tour as chef de cuisine at Café Boulud), he was faced with the harsh reality of life as a civilian cook: no prep cooks, no saucier, no daily deliveries—just him and his wife in their tiny Manhattan-apartment kitchen.Urban Italian is made up of the recipes that result when a great chef has to use the same resources as the rest of us. In these hundred recipes—covering four distinct courses, side dishes, and base recipes—Carmellini shows how to make stunning, soulful food with nothing more than the ingredients, techniques, and time available to the ordinary home cook. The food is sophisticated but also easy to make: lamb meatballs stuffed with goat cheese; veal, beef, and pork ravioli; roast pork with Italian plums and grappa; fennel with Sambuca and orange; and a honey-flavored pine nut cake.The book opens with a narrative (written by Carmellini with his wife and coauthor, Gwen Hyman) that traces Carmellini’s culinary education—a series of outrageous tales that will delight anyone who loved Heat or Kitchen Confidential. Also scattered through the book are short pieces on places and ingredients, placed alongside recipes to shed light on the history and practice of simple, beautiful cooking. This is a book you’ll find yourself using all the time—to cook from for weeknights and for special occasions, or just to sit down with and read. Publishers Weekly In one of the more creative yet accessible Italian cookbooks to come along, Carmellini (formerly chef of A Voce in New York City) presents spectacular recipes while opening a window onto his life with food, from his Italian-American boyhood and cooking school to revelations while traveling in Italy and being a top New York chef. An extensive personal introduction as well as ample side notes and recipe introductions offer extra insight into his approach to food. The recipes, which come from all over Italy and mix regional Italian and American influences, are arranged classically, from antipasti to dolci. Many seem typical Italian fare, yet Carmellini gives them an idiosyncratic touch that heightens flavors and makes them work for the modern cook, whether that means an intriguing beet and grapefruit salad or meatballs with cherries. Some recipes are simple but time-consuming, as he candidly admits, yet he walks through the steps so patiently that a determined cook at almost any skill level will manage. Carmellini shows why he is considered one of the country's best young chefs, and a natural teacher. (Oct.)Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

\ URBAN ITALIAN\ \ SIMPLE RECIPES AND TRUE STORIES FROM A LIFE IN FOOD \ \ \ \ By ANDREW CARMELLINI GWEN HYMAN \ Bloomsbury USA \ Copyright © 2008 \ \ Andrew Carmellini and Gwen Hyman\ All right reserved.\ \ \ ISBN: 978-1-59691-470-4 \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One TRUE STORIES\ LEARNING TO COOK isn't just about knife skills and timing and technique, and it's not all about that I-am-an-artist thing either, It's about who you are and how you deal with the world: with banging out a meal for six hundred on the fly, for example, or with a crazy restaurateur, or with a pack of starving models, or with three months without a day off. And it's about understanding that cooking is more than just applying heat to food in complicated ways: a good cook brings his or her life to the table, and sucks as much experience as possible from the world to do it. So my education in Italian cooking has happened in kitchens, sure, but also on bucolic hilltops and in train-station cafés in the middle of the night, in Jaguars and in a 1974 Fiat 127, in fancy restaurants and in tents, on the road pursued by the polizia and at Park Avenue black-tie events. It's not like a Hollywood movie, where you go into culinary school and come out with a big knife and a hot job; it's more like a bunch of crazy home videos-the kind of stuff that comes out at the end of the night, with old friends, when everyone's had a drink or three. Here are a few of my favorites from the Italian reel.\ My grandmother was Italian, in that old-school "if you're not suffering, you're sinning" kind of way. Her family, the Bertins, had drifted into northern Italy from their native France way back when, but she never had a lot of love for the French or their hoity-toity food. This whole "haute cuisine" thing, the idea that France was the cradle of restaurant culture-it was all garbage, Grandma said: if it hadn't been for Catherine de' Medici and her Italian cooks, the Frogs would still be boiling up chunks of meat and fat and calling it dinner. The Italians, they knew what flavor meant!\ But she always gave people their props, Grandma-and Auguste Escoffier, he was due his props, French chef though he was. She gave me his books when I was a kid-my first real cookbooks-and she told me stories about him. The greatest cook of all time, she said. Precision! Integrity! Ingredients! Now that was a chef! Her favorite story about Escoffier went like this:\ Once, Escoffier was making a banquet for three hundred people, a wedding. This was no big deal for Escoffier. Three hundred people was like nothing to him. Everything was timed perfectly; every dish went out gorgeous, and the people couldn't believe how great everything tasted. The dessert was soufflé, and it was supposed to go out right after a certain speech was made. It couldn't be served during the speech, because the speaker was the bride's father, a big important guy in Paris, but it had to come out as soon as he was done, or the timing would be off for everything for the rest of the evening. Escoffier knew the guy would talk for twenty minutes, which was exactly how long it would take to make the soufflés. So twenty minutes before the speaker was due to begin, he gave the signal, and all his cooks started cracking shells and separating the yolks and whites of six hundred eggs. And fifteen minutes before the toast started, the great chef and his cooks began beating the egg whites, because the most important thing, with soufflés, is to beat the eggs continuously-fifteen minutes without pause, as fast as you can. As soon as the speaker stepped up to the podium, glass in hand, the beating of eggs ceased, the soufflés went into the oven. Escoffier had a little drink-they all had a little drink-and they waited, quietly, so as not to disturb the soufflés. And at the twenty-minute mark, the soufflés were perfect.\ But this father of the bride, even though he was important, he was kind of a nervous guy, and so he'd had a bottleful of wine, more or less, before he got to the podium. When the twenty minutes were up, he was just getting warm, and he was so important that nobody felt like they could tell him to hurry up. Escoffier stuck his head out the kitchen door, and he listened, and it was clear the guy wasn't making any wrapping-up sounds. So he told his cooks to trash all the soufflés-three hundred soufflés!-straight out the back door to feed the beggars in the alley. The cooks didn't dare complain-yeah, precision, ingredients, creativity, the guy had it all, but Escoffier was not known for his patience, was not an easygoing, low-maintenance-type chef. They washed their bowls, went to the pantry, cracked another six hundred eggs. For another quarter of an hour-sweating, grunting, swearing-this kitchen full of men whisked the soufflés, biceps and triceps bulging, Again, the soufflés went into the oven. The cooks collapsed against the counters, dripping with sweat. Precisely twenty minutes later, they raised their shaking arms and-gently, gently-pulled the soufflés from the oven, Once again, each one was a thing of beauty, steamy and high and absolutely ready, right on time. The waiters stood at the door, poised, their smiles ratcheted tight.\ And still, the bride's father, drunk, important, more powerful than anyone else in the room, went on talking and talking, He remembered his childhood, the rope swing in his backyard, the time he cracked open his head on a rock hidden in the lake. (The cooks had thoughts, muttered comments.) He told the story of his first true love, of another woman who broke his heart, of the day when he realized that he would be rich. He talked of how the bride was the most headstrong child anyone had ever had to raise, but how she was worth ten of her brother, who seemed somehow to have no interest in money, not even in spending it, except on paint and books and food, fancy food, which he guessed was culture but what good did it do?\ Again, the alley door was propped open. Again, the beggars were treated to dessert. The kitchen boys were sent running to all the markets, to their grandmothers' and mothers' and aunties' houses, anywhere, everywhere, for more eggs. Again the eggs were broken, the whites beaten-the cooks shaking now, their arms spasming out of control, whipped egg white flying up, coating their eyebrows, their chins. The beating this time took twenty minutes, they were not so fast, and they tried not to weep directly into the bowls-the salt being very bad for the flavor. Escoffier, sweating through his chef's jacket, beat his eggs as though his arms were mechanical, magical, glaring out over the bowl, daring anyone else to give up. Again the soufflés went into the oven. The cooks slid to the floor, their backs against the counters, their knees bent up in front of them. Escoffier stood, arms crossed, terrible, serene. In the dining room, the guests, he could see, were slumping over their wine, turning their napkins into folded flowers, playing games with feet and fingers under the table. The father of the bride talked, and talked, and talked, and the cooks lost hope: they would be making soufflés over and over, until their arms fell completely off, until all the eggs in Paris were eaten up by all the beggars in Paris and the chickens were all dead from exhaustion. But just then-just at twenty minutes, just when the soufflés were just done-the father of the bride found that his glass was empty. He hoisted it high above his head. "To the bride!" he shouted. "To the bride!" the crowd replied, deeply grateful, loving the bride, loving the empty glass. And the kitchen door swung open, right on time, and the waiters in their spotless jackets emerged, military, precise, bearing three hundred steaming, high-domed, light-as-air soufflés.\ THAT, MY GRANDMOTHER SAID, WAS COOKING.\ When I was fifteen, I scored my first real restaurant job, at this Italian place down in the valley. To get there, you drove past a bowling alley, a couple of trucking companies, some warehouses, right down almost to the edge of the canal. This was some time after the Cuyahoga River caught fire, but way before Cleveland started cleaning itself up-so it wasn't exactly the kind of neighborhood where you'd expect to find women in Dynasty outfits and big hair or men in fancy Italian suits, but there they were: back in 1987, that restaurant was smokin', packed every night, four hundred covers or more. The front was all done up in greens and mauves and glass block; there was a backyard garden with brick walls, trellises, vines, the whole '80s Hollywood look. It was the place to go for business lunches or fancy dinners, the place everyone made reservations for anniversaries, birthdays, proposals (of all kinds).\ I thought I'd learn about food at the Italian restaurant. About the business. I was a kid from the suburbs who played basketball and messed around on the guitar. What did I know?\ And I did learn things. I saw all kinds of stuff that fifteen-year-olds don't usually see. Big dudes with nicknames, in good suits, making shady deals at the back tables. Bringing their mistresses one night, their wives another, hookers or strippers from down the street when things were slow. Handing off packages under the table. It was one of those guys-he came in with his wife sometimes, his kids-who offered one of the hostesses four grand to spend the weekend with him. (When she turned him down, her friend stepped up. "I'll do it!" she announced, cheerleader chipper in her big hair. The guy looked her up and down, pulled out a wad of dough. At the end of the shift, there he was, waiting in his Lincoln.)\ Women would go into the bathroom in twos and threes, coming out sparkling and sniffing. Cooks disappeared into the walk-in to smoke pot during service, blowing the smoke into the fan intake so it would disappear outside; by the end of the night, you could get stoned just by standing out by the exhaust vent, near the garbage cans in the alley.\ I worked every job there was at that restaurant. I started out bussing tables, I hosted, I worked bar-back-and I made good money, up there in the front. But I wanted to cook, and the place had a reputation for serving the best Italian in town, so I asked-asked!-to go work with the mooks in the kitchen. I worked my way up through every station: from salad to fry station to sauté and so forth. On Saturday mornings, I would show up at eight A.M., prep the entire cooking line, and then put together each and every special of the day, all by myself.\ The menu wasn't all Italian: no smart restaurateur in that time and place would have gone that way. There was the typical '80s American stuff: burgers at lunchtime, that ubiquitous California chicken salad with fried wonton strips and canned mandarin oranges. I'm pretty sure even Indian restaurants had that California salad on the menu back then. And we did steaks and chops, of course, for all those guys with big shoulders: on Saturday nights, working grill, I could turn out three hundred of those. But mostly it was Italian. That's why I was there. I wanted to learn about authentic European cooking. This, they told me, was the real thing.\ (This was way before I went to Italy.)\ The menu featured antipasti, lots of pastas, of course. Chicken parmigiana, veal parmigiana. There was always a veal scallopini of the day and a chicken scallopini of the day. This was, in fact, amazing: "of the day" didn't just mean a weekly rotation. It meant that there was a different veal scallopini and a different chicken scallopini every single day of the year, 365 variations. Veal scallopini with tomato-vodka sauce. Chicken scallopini with Marsala and mushrooms. Veal scallopini with sauce picante. Chicken scallopini with Frangelico, cream, and crushed-up hazelnuts. Every single day there was a different chicken scallopini and a different veal scallopini, always served over fettuccini or rice pilaf (your choice!)\ Everyone I talked to-the cooks I worked with at the catering place, Pete at the Italian restaurant, my friends' parents-said that the way they were doing things, the way they cooked "I-talian food," was "the way they do it in the old country." So that's what I thought Italian food was: pasta so soft it turned to glue in your mouth; "red sauce" and a large, overspiced ball dumped on the very top of a pile of noodles; cheesecake with canned fruit topping. THREE HUNDRED AND SIXTY-FIVE FLAVORS OF CHICKEN SCALLOPINI.\ When I was eighteen, I finally made it to Italy for the first time. We went on a huge family trip-aunts, uncles, cousins, crammed carloads of Italian-Americans barreling through the Old Country. My oldest uncles were born in Italy, and they wanted to show us all what it was really like. I was psyched-my first plane trip, my first passport. I knew exactly what it would be like. I'd seen the movies; I'd read the books; I'd heard my uncles' stories. I'd ride a motor scooter fast over the hills, drink espresso in town squares, hang out on Mediterranean beaches crowded with topless European women. Chase curvy Italian girls with long dark hair and sexy smiles. La Dolce Vita.\ Well. So.\ First of all, my uncles, who were, granted, born in Italy, wanted all of us to pass as gen-u-ine Italianos. Didn't matter that my cousins and I didn't speak a word of Italian that wasn't about food or swearing. We all had to wear long pants and collared shirts every day, in the heat of the Italian summer, jammed into a van without air conditioning, with all our relatives. So I didn't look like an ugly American in a fanny pack and bike shorts, but I didn't exactly look like one of those cool, carefully disheveled Italian dudes either. By the time I crawled out of that thousand-degree van for our first stop of the day, I was wrinkled, sweaty, sodden, and totally pissed off.\ Not that it mattered, since there were definitely no beaches to hang on and no girls to chase. Instead, we stopped the car at every church, every monastery, and every castle between Rome and Udine. And at any place that anything historical at all had happened-not just World War I and World War II, but going all the way back to the Peloponnesian wars. Lot of history in Italy. We'd stop, stand around old stone walls or empty fields or town squares, take a picture. I'd kick a rock and stare out in the distance, soulful, sweating. We'd down espresso served by some ancient Italian woman in a headscarf. Then we'd get back in the van, taking a last deep breath of fresh air before crawling back into that smelly oven. We'd get lost, over and over again, driving through the hills past farmhouses and car repair joints and sofa factories on the outskirts of town. "Follow da sun!" my uncle would holler, like we were birds, or eighteenth-century sailors.\ We didn't eat in any fancy places on that trip-we couldn't afford ristorantes, and my uncles weren't the type to sit around in a café by a fountain with a guidebook and a pack of cigarettes. So it was trattorias, rest-area espresso joints, osterias, and quick lunches of bread, wine, and cheese in the back of the van. None of it had anything to do with the Italian food I'd eaten in restaurants and at friends' tables all my life. No frozen pasta; no "red sauce"; no cheesecake with canned fruit topping; no scallopini of any kind. Everything was fresh, made five minutes ago, and it had actual, distinct, vibrant flavors. In Friuli, I had white asparagus for the first time-in a risotto, even: not a rice-pilaf-from-a-box-with-cream, like we'd been serving in the restaurant back home, but a whole different thing, a course of its own, soft and comforting and creamy and fresh-tasting. Even the espresso in the rest-stop bars was the best I'd ever tasted. It twisted my head right around. This? This was real Italian? Like they make it in the old country?\ THIS WAS GOOD.\ For my uncles, my re-education was a challenge: like deprogramming a cult member. They were going to beat the mid-westerner out of me, no matter how painful the process might be. The very first night in Italy, after we got off the plane at the Malpensa airport in Milan, we stopped at this trattoria my uncle knew for lunch-a very local, very typical kind of place. I'd been awake the whole time on the plane, too psyched to sleep; I'd had two espressos on the way to lunch. I was wired, jumpy. 1 couldn't focus on the menu, couldn't understand the Italian, and finally I just gave up. "1 order for you," says my oldest uncle, and he looks up at the waiter, and he grins, and he says, "Something something cavallo something something per favore." I'm thinking, "Cabbage? I'm getting cabbage?" (because I've been studying gastronomic Italian, and I'm pretty good with the vegetables). I'm drinking wine, looking around, listening to all the Italian around us, and I can't believe I'm here-and I'm so tired I'm sort of hallucinating, almost, things spinning and swimming around a bit, like I'm really drunk but totally hopped-up at the same time. And then the waiter appears with this plate, and it's got this pile of ground meat in the center, uncooked, with some olive oil, some arugula, a bowl of crunchy bread on the side. (So I guess it's not cabbage. Right. Cabbage is cavolo.) The meat was raw-but that was okay, I was going to be a cook, I knew from French food, it was tartare, it was cool. "What is it?" I asked my uncle. "It's good! You'll like it! Eat!" he answered. I wasn't going to let him think that I was one of those ugly American kids in Europe who asked for soda pop at the table and snuck away to McDonald's first chance I got. So I picked up my fork and I started mixing the meat with the olive oil, piling it onto the bread, tossing the arugula on top. A kind of gamey beef flavor, rich, deep. Local cows, I thought, picturing fields of wandering bovines, muscular, natural. I ate every bite.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from URBAN ITALIAN by ANDREW CARMELLINI GWEN HYMAN Copyright © 2008 by Andrew Carmellini and Gwen Hyman. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.\ \

Contents INTRODUCTION: TRUE STORIES....................32A NOTE ON THE RECIPES....................36ANTIPASTI....................88PRIMI....................160SECONDI....................206CONTORNI....................238DOLCI....................282BASES....................302A GUIDE TO LOCATIONS....................307ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................308INDEX

\ From the Publisher\ A Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year "Creative yet accessible. Carmellini presents spectacular recipes while opening a window onto his life with food, from his Italian-American boyhood and cooking school to revelations while traveling in Italy and being a top New York chef. Carmellini gives [the recipes] an idiosyncratic touch that heightens flavors and makes them work for the modern cook at any skill level. Carmellini shows why he is considered one of the country's best young chefs, and a natural teacher."—Publishers Weekly (starred) \ “Andrew Carmellini’s Urban Italian is that rare breed of cookbook: written by a skilled, top-tier professional, yet at all times accessible, unintimidating, and inspiring to the home cook. In short, it’s everything a cookbook should be. The conversational style provides both a thrilling introduction and the feeling, while cooking, that the chef is standing next to in the kitchen, forgiving your mistakes, urging you along, painlessly expanding your reservoir of knowledge. In a world awash with Italian cookbooks, this one's a must-have.”—Anthony Bourdain\ “Andrew Carmellini is an enormously talented chef who brings a distinctive style and voice to his restaurant. Urban Italian captures that style and voice for the home cook with intriguing recipes—and also with great stories about the cook’s life, written with a candor and bravado not typically found in chefs’ cookbooks. A terrific book.”—Michael Ruhlman\ "Andrew’s passion for Italy is contagious. Urban Italian is entertaining, informative, and witty." —Eric Ripert\ “This would be a great book if it did nothing more than faithfully capture between covers the great food served at A Voce. But, marvel of marvels, the modest-but-confident chef I've admired for so long for his cooking can also write his ass off. Urban Italian is every bit as intimate, profane, soulful, and amusing as Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential. To paraphrase Andrew himself on the subject of cooking, this book engages your senses, takes your mind off your day-to-day problems, and makes both the reader and (I'm pretty sure) the writer happy.” —Sara Moulton\ “Like many Italian American chefs, myself included, Andrew had to go through France to get to Italy. Urban Italian takes the reader on that journey. Fabulous recipes, of course, but just as important are the stories that informed the heart and soul of this great chef.” —Tom Colicchio\ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn one of the more creative yet accessible Italian cookbooks to come along, Carmellini (formerly chef of A Voce in New York City) presents spectacular recipes while opening a window onto his life with food, from his Italian-American boyhood and cooking school to revelations while traveling in Italy and being a top New York chef. An extensive personal introduction as well as ample side notes and recipe introductions offer extra insight into his approach to food. The recipes, which come from all over Italy and mix regional Italian and American influences, are arranged classically, from antipasti to dolci. Many seem typical Italian fare, yet Carmellini gives them an idiosyncratic touch that heightens flavors and makes them work for the modern cook, whether that means an intriguing beet and grapefruit salad or meatballs with cherries. Some recipes are simple but time-consuming, as he candidly admits, yet he walks through the steps so patiently that a determined cook at almost any skill level will manage. Carmellini shows why he is considered one of the country's best young chefs, and a natural teacher. (Oct.)\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ Library JournalCarmellini is a talented New York City chef who recently left the three-star Italian restaurant A Voce, and his many fans are eagerly awaiting his next venture. He has cooked in Italy and at Café Boulud, among other high-end restaurants, but while he was waiting out long delays before opening A Voce, he started cooking at home every night. He wanted to make, he writes, "Italian food that was all about New York," and these recipes became the basis for both his restaurant menu and this book. Cooking in a tiny Manhattan kitchen without a professional brigade de cuisine was a reality check, and while the recipes are sophisticated, they are very user-friendly and eminently doable for the home cook. Carmellini's coauthor is his wife, a food writer and professor, and the text is readable and highly entertaining. Recipes include substitutions for more exotic ingredients, advance prep notes, and thorough explanations of each step, with striking color photographs of most dishes and helpful step-by-step photos. Highly recommended.\ \ —Judith Sutton\ \