Visualizing American Empire: Orientalism and Imperialism in the Philippines

In 1899 an American could open a newspaper and find outrageous images, such as an American soldier being injected with leprosy by Filipino insurgents. These kinds of hyperbolic accounts, David Brody argues in this illuminating book, were just one element of the.visual and material culture that played an integral role in debates about empire in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America.\ Visualizing American Empire explores the ways visual imagery and design shaped the political and...

Search in google:

In 1899 an American could open a newspaper and find outrageous images, such as an American soldier being injected with leprosy by Filipino insurgents. These kinds of hyperbolic accounts, David Brody argues in this illuminating book, were just one element of the visual and material culture that played an integral role in debates about empire in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America.Visualizing American Empire explores the ways visual imagery and design shaped the political and cultural landscape. Drawing on a myriad of sources—including photographs, tattoos, the decorative arts, the popular press, maps, parades, and material from world’s fairs and urban planners—Brody offers a distinctive perspective on American imperialism. Exploring the period leading up to the Spanish-American War, as well as beyond it, Brody argues that the way Americans visualized the Orient greatly influenced the fantasies of colonial domestication that would play out in the Philippines. Throughout, Brody insightfully examines visual culture’s integral role in the machinery that runs the colonial engine. The result is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of the United States, art, design, or empire.

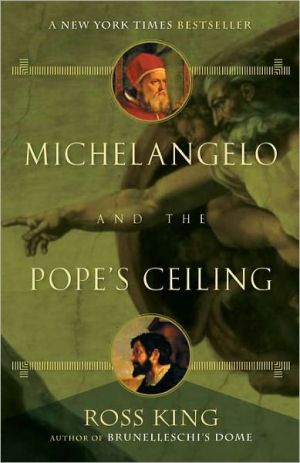

Visualizing American Empire\ Orientalism and Imperialism in the Philippines \ \ By DAVID BRODY \ The University of Chicago Press\ Copyright © 2010 The University of Chicago\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-226-07534-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Strange Travelogues \ Charles Longfellow in the Orient\ Charles Longfellow (1844–1893) never intended to create an archive that would present an objective view of Asia. Nor did he have the patience for such an endeavor. "Charley," the eldest son of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (arguably the most famous poet in nineteenth-century America) left Cambridge, Massachusetts, to travel in Asia from 1871 to 1873. There are plenty of reminders, or souvenirs, of his adventure, including letters, photographs, objects, and journal entries, but nineteenth-century publishers never codified the record of his trip in books or articles. Charley kept a personal record. The tone of his visual and written account is not consistent with those of many artists, scientists, and thrill seekers who went east with the hope of plotting knowledge about Asia onto a grid of perception, providing their curious Western audience with information about the Orient through collections. Longfellow's chronicle is sexy, disorganized, and, most problematic to a researcher, fragmented; his representations of strange experiences would have befuddled most Americans seeking a sense of order about the world.\ During the postbellum period Longfellow traveled to Japan, Cambodia, Thailand, China, Vietnam, India, and the Philippines. While his literary father repeatedly asked him to return home and stop spending the principal of his inheritance, Charley remained in Asia and never shied away from extravagance. Approximately 350 photographs, hundreds of objects, numerous letters, and pages of journals indicate his lack of interest in fiscal concerns. Longfellow materially exemplified his contemporary Ralph Waldo Emerson's notion of the "transparent eyeball," voraciously taking in everything that lay in his path and recording these impressions through the lens of his own writing, other people's cameras, and a capacious desire to collect. While the Longfellow archive is somewhat of an anomaly in terms of its unusual content, Charley's longing to domesticate, catalog, and stereotype Asia was a product of American Orientalism during the 1870s.\ Although most nineteenth-century Americans traveling in Asia stayed in major cities and ports, Longfellow often left this well-mapped terrain to explore areas that enticed his curiosity. The writing he undertook and the photographs he collected in these remote regions, coupled with his impressions of metropolitan areas, form an early example of an American Orientalist archive. Longfellow's desire to gain a cultural understanding of these distant places is obvious, but what also emerges as we look at the copious material he left behind is one man's hope of attaining access to a part of the world that he understood as exotic, sensual, and completely separate from the Boston Brahmin upbringing he was trying to escape.\ Longfellow struggled against the confines of his family's class consciousness; he seemed to loathe his refined childhood. While the Longfellows expected Charley to attend college, get a proper job, and heed the parameters of New England society, he refused to entertain his parents' wishes. At the age of eighteen, shortly after his mother's death, he left home and joined the Union cause in 1863. His father was dead set against him serving during the Civil War, but Charley saw the war as an opportunity that would help him quench his thirst for adventure. For ten months he was a second lieutenant, but during the Battle of New Hope Church he was injured. Photos of his shoulder and back display the scars of battle that forced Longfellow to return home and begin his unusual journey as an eccentric obsessed with travel.\ Longfellow's experiences in Asia are an early example of an American interest in gaining knowledge about the ambiguously defined Orient. The Longfellow archive is a visually mediated scape that showcases bodies, both his own and those of his "Oriental" subjects, as a manifestation of Orientalist desire. It was through the photographic representations of others and the decoration of his own body that Longfellow deployed the visual to incite fantasies about the cultural Other. His portrayal of the body signified stereotypes of non-Western cultures and portended the Philippines as a future site of American representational interests and global pursuits. Longfellow's travels were particularly important because he was one of the first Americans I have found who spent time in the Philippines, the site in the Orient that became critical for the project of American empire at the turn of the century.\ Life with the Ainus\ Writing from San Francisco in early June 1871, Charles declared to his father that he "suddenly decided to sail for Japan today." He arrived in Japan later that month and spent most of the summer traveling through various parts of the country and becoming acquainted with Yedo, the city that would become his home base. After this initial summer in Japan, Longfellow spent time with a native Japanese tribe called the Ainus, located in the northern part of the country. In September and October 1871, he wrote extensively about the Ainus, and he purchased photographs to document these "quiet, amiable people."\ One of the photo albums with Ainu images in Longfellow's collection has the name Nagootchi on a blue cover and displays an arrangement of twenty-one photos along with captions written in what was probably Nagootchi's (the possible photographer's) hand. The Ainus would have interested Charley because they fit his notion of a travel oddity; they were so different from life in Cambridge that he quickly focused his attention on capturing their unique cultural features through writing and photography. The Ainus lived on the northernmost island of Japan, Hokkaido, which was far from the metropolitan areas of the nation that were struggling with an effort to modernize and remake their image as more Western during this period. When the emperor Meiji came to power in 1868, the Japanese government did not know what to do with the Ainus, whose customs were antithetical to the Meiji wishes for an industrialized and modern Japan. According to historian Richard Siddle, the Meiji enforced the transformation of the Ainus' landscape "into an internal colony of the new Japanese state, a strategic 'empty land' to be settled by Japanese immigration and developed along capitalist lines" and "these policies required the dispossession of the Ainu as a prerequisite." Like the Native Americans, the Ainus hindered capitalist expansion. Thus, the Japanese government thwarted their preindustrial culture through an imperial project that posited the Ainus as subjects who needed to be assimilated.\ The blue photo album documents what Longfellow understood as an untainted people who had not yet faced radical changes brought about by modern life. For instance, the fifth image in Nagootchi's packaged ethnography of the Ainus represents huts and storage facilities (fig. 1). The text explains that the "photograph represents the Ainos [sic] huts, and store house at Otarnari in a western coast of Yezo. These huts and store houses are thatched with bamboo leafs, the Ainos girl and boy carrying a baby, the other two shoe [sic] their dress." If we assume that Longfellow purchased this album as a souvenir of his trip—one of several souvenirs he took home from Asia—than this particular item, inscribed with exacting language where every caption begins with the phrase "This photograph represents," would have been very desirable. Whether the hand is that of Nagootchi or another individual who worked with Nagootchi, the author's attempt at providing definitive meaning and clear objectivity appealed to the American tourist.\ The photographs, like the captions, create a sense of ethnographic certainty through declarative descriptions of the images. In the fifth image, several huts circle the ground at the center of the photograph. Each hut is, as the caption states, "thatched with bamboo leafs." In the middle ground of the photograph are five Ainus who are, without the help of the authoritative caption, not clearly discernible. Huts appear in several of the other images in Nagootchi's album. Even though many viewed the hut as the architectural prototype for future building, Western culture in general understood the hut's impermanence as uncivilized and culturally unstable, connoting the world of the primitive through its inhabitants' adherence to a type of ephemeral building.\ Longfellow wrote about Ainu dwellings in his journal. "They all seem poor, but to want for nothing, as all the houses we entered were comfortable in a smoky sort of way. But I must describe them! They are as a rule quite large, thatched walls and roofs, no chimney, but a large hearth in the center of the floor is what the fire is made on, the smoke finding its way out at the windows and sometimes by a small hole in the roof." He provided specifics about some of the objects in these spaces and ended his descriptive paragraph by noting that "scarcely ever in the day time does one find any young men about these houses, they all being off fishing or hunting." Like the photographs of the Ainu homes, the journal lent an air of domestic regularity to these spaces; there were hearths, and men and women had separate functions within this sphere. Indeed, Charley's own sense of the domestic probably influenced his perception of Ainu housing.\ Impermanent building was just one of the ways in which Longfellow signified the Ainus as ethnographically different. In 1871, on the last page of his journal, Charley wrote:\ The name Ainu means hairy men in their language, which is quite different from that of Japan—the two peoples not understanding each other's language.\ They were found in Japan by the Japanese occupying Nipon and Yesso, but many years ago, they had a severe war with the Japanese and were driven from the island of Nipon and the southern part of Yesso.\ They are said to have been a very warlike people, but they seem very mild, devoting themselves to hunting and fishing exclusively, not tilling the soil.\ They wear their hair and beards long and have a great deal of hair on their bodies even down the back bone. Their features are regular and some even fine looking. their average height is about five feet seven or eight inches. They are as a rule very muscular.\ Their women have a large mustache with pointed ends covering both the upper and under lip tattooed into their skins, or rather cut in with knives, at the age of fifteen or thereabouts.\ Although the Ainus were found on Japanese soil, they looked, acted, and spoke in a fashion that distinguished them from other Japanese people Longfellow encountered. His writing, like the photographs he collected, is akin to other examples of nineteenth-century ethnography in which categorizing difference, making distinctions, and pointing out racial characteristics are imperative.\ The images of huts, and other photographs, such as a three-quarter-length portrait of an Ainu woman replete with a tattooed mustache, visually augment Charles's writing. Image and word worked together, allowing Charley to bring home souvenirs from his travels that would have reminded him of his trip and provided a venue where he could share his experiences with others. Susan Stewart claims that we "do not need or desire souvenirs of events that are repeatable. Rather we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us, events that thereby exist only through the invention of narrative." Charles devised a travelogue about his own experiences in Asia through the interrelated acts of writing and collecting images. His photographic and journalistic souvenirs made his trip meaningful. Indeed, the images of the Ainus constitute an artificial visual scape that Longfellow was able to carry as a souvenir when he returned to the United States. Longfellow may have orchestrated what photographs Nagootchi took and how his camera should frame these exotic natives. From there, the images were developed, ordered within the pages of the album, and made available for display to a Western audience. Again, these were not popular images—the photos probably did not circulate beyond family members and close friends—yet they manifest fantasies about other parts of the world that were becoming more widespread during this period. As later chapters reveal, these photos were typical for projects that visualized other geographic locations later in the nineteenth century.\ Inking, Dressing, and Going Native\ Perhaps the most peculiar piece of evidence that suggests Longfellow's commitment to the personal are the tattoos he brought from Asia, making his body into a visually mediated scape on which his travels were recorded in ink. "Injecting pigments" into the skin with needles creates tattoos, which have a long and complicated history in both Japanese and American culture. Longfellow acquired most of his tattoos, which covered his arms, his back, and his chest, during the 1870s and 1880s. One of his tattoos, representing crossed flags on his arm, was completed during the Civil War while he served in the Union army. Included also in the hundreds of photographs he collected are images that show Japanese subjects with tattoos, such as the Ainu women with their tattooed mustaches.\ The riot of colors and shapes that covered Longfellow's body included a Japanese woman dressed in a kimono on his arm (a symbol of potential eroticism that reappears in numerous photographs that Longfellow collected), a large carp fish on his back (a symbol of virility), and an image of the Japanese goddess Kannon in the mouth of a dragon on his chest (a symbol of protection for sailors). All these corporeal signifiers in ink were, like the photographs he collected and the writing he did while in Asia, souvenirs that marked, and in this case inscribed on his skin, the narrative of his travels. Longfellow's trip adorned his body. The tattoos were a form of writing, a type of language injected into the body that disclosed representational import.\ Longfellow had photographs taken that reveal his desire to document how he inked and dressed his body with references to Japan in a fetishistic manner. Two photographs, one of his back (fig. 2) and one of his chest (fig. 3), depict his tattoos, but in both images his face is obscured. In the photograph of his back, dominated by the carp, his back is to the camera, and in the image of his chest, his face is hidden by the brim of a hat and a mask that covers his eyes. Longfellow tattooed his body as a way to subvert the cultural norms of genteel Brahmin culture. By dressing Japanese (fig. 4) and tattooing his body with Japanese imagery, Charley was reassuring himself and others that he had been in Asia. Additionally, these portraits made Longfellow into a fetishistic site for the display of the cultural Other. By dressing up, or wearing the garb of the Other, Longfellow created a type of cross-racial identification. Clothing, which he repeatedly deployed as a way to play Japanese, could be removed, while the tattoos were permanent, a type of indelible fetishistic mark. By capturing this transformation with a camera—the nineteenth-century's great documenting device—Longfellow recorded his fetish. He also created a fetishistic object, the photograph, by using his body as a subject. In short, Longfellow utilized his body and photographs of his body as visual scapes that represented his Orientalist fixation.\ Longfellow's physical transformation exposed the ambiguities of his desire to become the Other, or the object of his own ethnographic gaze. He went to Asia to witness, observe, and become titillated. Charley collected photographs, wrote, and purchased souvenirs. The photographic and written collection he kept became a distancing mechanism that allowed him to separate himself from the subject of his gaze through the lens of the camera and the ink of his pen. However, wearing the clothes of the Other and being tattooed with Japanese imagery reveals a type of collecting that Charles did on his actual body. This brought the experience of Asia closer to his own physical sense of self; gone was the critical detachment of ethnographic observation. Take, for instance, the image that represents Longfellow in samurai garb (fig. 4). In this full-length portrait, he stands confidently in a photographer's studio, his body clad in the traditional layered robes of a samurai and his feet in sandals. In his right hand he holds a fan, and in his left hand he grips a samurai's sword called a katana. By taking on the sartorial signs of a Japanese samurai, Longfellow became a hybrid of both Western and Eastern cultures. The trope of the samurai warrior heightened his own masculinity, as he created a self-made admixture of cultural typologies.\ Charley's turning away from the camera, his disavowal of self, is also significant in the tattoo photos (figs. 2 and 3). By refusing to face the lens in these two images (by either covering his face or turning his back) he shed his former self for a new persona. That Orientalized self, Charley's new identity, obscured his Caucasian face, which appeared, in his estimation, too white, too refined, and too normative. He reinvented who he was while in Japan, and when he had completely transformed his character to the best of his abilities, he masked his former identity through concealing gestures, utilizing his body as a visual scape to cultivate a new identity that elided his former self. Longfellow knew that his white body lay behind the shroud of Asian symbolism, but the formation of a hybridic display (the combination of a white body with Japanese accoutrement) allowed him to represent his newly invented nature.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Visualizing American Empire by DAVID BRODY Copyright © 2010 by The University of Chicago. Excerpted by permission of The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

List of Illustrations Introduction1 Strange Travelogues: Charles Longfellow in the Orient2 Domesticating the Orient: Edward Morse, Art Amateur, and the American Interior3 Disseminating Empire: Representing the Philippine Colony4 Mapping Empire: Cartography and American Imperialism in the Philippines5 Celebrating Empire: New York City’s Victory Party for Naval Hero George Dewey6 Building Empire: Architecture and American Imperialism in the Philippines Conclusion: Taft Decorates the White House Acknowledgments Notes Index

\ Kristin Hoganson“Much of the historical writing on U.S. imperialism in the Philippines pays scant attention to wider contexts, but Brody situates American endeavors there against the larger backdrop of Orientalism. He finds that visual media played a major role in shaping Americans’ perceptions of the Philippines, indeed, that the public eye focused on the events and ideas that lent themselves to sensational visual treatment. A creative work of interdisciplinary scholarship, Visualizing American Empire reframes our understanding of this important topic.”\ \ \ \ \ \ Gary Y. Okihiro“Visualizing American Empire works the visual archive of Orientalism’s ‘the Philippines’ in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. More than an imposition of imperial power over the Orient, this remarkable study shows, these ‘visual scapes’ are fluid, contested spaces that convey and enable complex and even contradictory meanings.”\ \ \