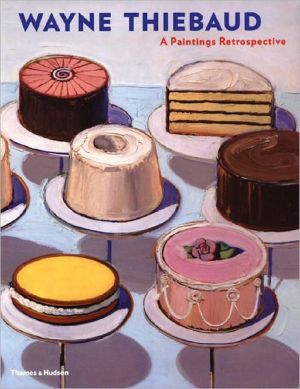

Wayne Thiebaud: A Paintings Retrospective

Wayne Thiebaud, the California-based painter, has produced works of complexity and distinction that appear deceptively simple in terms of subject matter and in their presentation yet draw on many historical sources.\ In fact, Thiebaud is part of the grand tradition of representational art from Chardin and Manet to the American Realist masters such as Eakins and Hopper. Best-known for his deadpan still-life paintings of cakes, pies, delicatessen counters, and other consumer goods, Thiebaud has...

Search in google:

Wayne Thiebaud, the California-based painter, has produced works of complexity and distinction that appear deceptively simple in terms of subject matter and in their presentation yet draw on many historical sources.Publishers Weekly"He is an American painter, someone who paints for a living and whose subject, for all its formal perfection, is what we are to make of American abundance," writes New Yorker art critic Gopnik in his long, in-jokey introductory essay to Thiebaud's oeuvre now touring the country as a retrospective. As Gopnik makes clear, Thiebaud is famous for his lush early '60s paintings of cakes, other sweets and people eating them, but this book and the exhibition it documents--put together by chief curator Nash of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, who also provides an essay--reveal the painter to be preoccupied with a larger slice of American life. The impossible perspectives and multigraded blues and yellows of the cityscapes here seem more bizarrely true to San Francisco than stills from Vertigo. Heavy Traffic, Deli Bowls, Tie Rack and Rabbit are just what they say they are, yet their surfaces coax us into looking at them harder and longer than such banal objects could possibly entice on their own. Such dressings-up themselves are commonplace in media-saturated American life, and Thiebaud redirects their energy unerringly throughout the 160 illustrations here, most in color. One might wish for a less insidery guide to the work than Gopnik's, but the panache of his biographical prose carries readers right into the paintings, well and comprehensively selected by Nash, whose own essay provides welcome detail on Thiebaud's working life. (Aug.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Unbalancing Acts:\ Wayne Thiebaud Reconsidered\ STEVEN A. NASH\ \ \ With all the modern mechanical aids, with the cinema, with film, and everything else, how are you going to trap reality, trap appearance without making an illustration of it? The painter has to be more inventive.... He has to reinvent Realism.\ —FRANCIS BACON, 1985\ \ \ I think we have barely touched upon the real capacity of what realistic painting can do.\ —WAYNE THIEBAUD, 1968\ \ \ For today's artists, Realism is a risky option. Faced with so long and rich a visual tradition and challenged by strong modernist pressure towards the nonobjective and conceptual, how is it possible to sustain and also reinvigorate basic Realist values? Wayne Thiebaud found his own way. For over forty years he has worked prolifically in a variety of media to define a figurative idiom whose individualism lies very much in his ability to balance apparent opposites: representationalism and abstraction, seriousness and wit, immediacy of touch and rigorous compositional control. His work has a unique look. In its focus on the here and now of consumer goods and deli cuisine, portraits of friends and associates, grand landscape views near his Northern California home, and the improbable geometries of the San Francisco cityscape, it tells a colorful story of popular culture and aspects of the world around us. Although the connections often drawn with Pop Art are overstated, it does share with that movement a fascination with brash Americana. For all of its brightmodernity, however, Thiebaud's art depends heavily on tradition. He readily pays homage to a long genealogy of favorite artists, including such diverse figures as Hopper and Mondrian, Chardin and Sargent, Morandi and Diebenkorn. As Thiebaud himself put it, "I'm very influenced by the tradition of painting and not at all self-conscious about identifying my sources.... I actually just steal things from people that I can use—just blatant plagiarism."\ This admittedly larcenous interest in the past is just one of the factors that make Thiebaud's art more complex than is sometimes assumed. His development over the past forty years has been gradual and sustained, not marked by dramatic shifts of style but inflections of handling and expression arising from a steady examination of recurring themes. He has gone in his own direction with little concern for broader artistic trends, and at age eighty is working with as much vigor and inventiveness as ever. For all of Thiebaud's accomplishment, however, a certain critical ambiguity continues to surround his work, from the early confusion of his still-life paintings with the Pop Art movement to the surprise and uneasiness elicited by his recent landscapes with their jarring blend of abstraction and Realism. Critical and historical assessments of his work often seem to trip over the quandary Just Where Does He Fit In? It has been too easy to dub Thiebaud with respectful humor the "Chardin of the cake shops" and pigeonhole his work as "California Pop."\ On the occasion of the most complete retrospective of his paintings ever organized, it is particularly appropriate to review Thiebaud's development and identify those qualities that make his art distinctive, giving it depth and lasting impact. Certain issues require examination. To what degree, if any, does Thiebaud's work partake of the social criticism fundamental to most Pop Art? He has long described his art as a merger of the perceptual and the conceptual. What is the nature of the abstract-figurative dialogue that fortifies the best of his imagery? What historical relationships have been the most meaningful for his development, and what, if anything, can be identified as truly "Californian" about his work? Such inquiry may get us closer to the heart of Thiebaud's art and let us better understand its perspective on the topographies, natural and cultural, of American life.\ Thiebaud was a late starter. Out of his school-age experience with cartooning, theatrical productions, and poster design came an ambition to pursue a career in commercial art, whether as advertising designer or cartoonist, and a number of positions he held as a young man called upon his talents in these fields. As is often noted, he even worked in the Walt Disney Studios, although briefly, and he still holds today a high regard for animation and cartoon artists. To this background can be traced predilections of draftsmanship and composition—for example the tendency towards a reduced, stereotypical essence of form; the clean layout of objects against a blank background; and strong lighting effects derived from theatrical spotlighting—that stayed with him. It was not until he was almost thirty years old, however, that the notion of becoming a painter struck home, in large part under the encouragement and inspiration of his friend and fellow artist Robert Mallary.\ To obtain formal art training and a teaching certificate, Thiebaud enrolled under the GI Bill first at San Jose State College and then at California State College in Sacramento, where he received a teaching appointment at Sacramento Junior College in 1951 while still in graduate school. As he worked on his graduate degree and then began his teaching career, he experimented widely with different media and stylistic approaches. The review of a range of his earliest paintings, most of which have never been published, suggests an earnest if tentative search for a personal and somehow progressive means of expression (figs. 1-3). Through Mallary and Thiebaud's involvement in several art exhibitions in Los Angeles he met a number of that city's most prominent artists, but in Sacramento he found himself far removed from major art centers, which he eventually remedied by organizing a series of trips to the East Coast. The impact of European modernism so strongly felt during the 1940s in New York was much less direct and immediate in the West, and Thiebaud's exposure to modernist trends came mostly through the work of artists such as Lyonel Feininger, Eugene Berman, and Rico Lebrun, translated into his own early efforts as mild doses of Cubism and Expressionism. Ambitiously interested even at this early period in different avenues of work—from printmaking and theater design to sculpture, public murals, and film—Thiebaud began to build a regional reputation through exhibitions in and around Sacramento and San Francisco and by an energetic pursuit of whatever opportunities came his way, including a number of design commissions for performing arts productions and even the organization of annual exhibitions at the California State Fair and Exposition.\ With the growing hegemony during the 1950s of Abstract Expressionism as a force in American painting, Thiebaud was not able to resist the pervasiveness of its influence. During travels to New York, he met and made friends of several of its leading proponents, but even before this, his paintings manifested several of its trademark stylizations, including rapid-fire lacings of thick brushstrokes, strong chords of color, and even the use of reflective metallic paints (which also ties to his early interest in Islamic and Byzantine art). Ribbon Store from 1957 (cat. 3) is one of the boldest and most nearly abstract works Thiebaud produced during this period. With a heavily charged brush and wide strokes, he built up a mosaic-like pattern within which the basic, simplified motif of a shop window practically dissolves into the pure dynamic of energetic form and color. In works such as Cigar Counter of 1955 and Pinball Machine of 1956 (cat. 1, 2), a flickering play of brushwork and light absorbs the subject, although the breakdown of solid form is much less complete. It's as if certain mannerisms were being applied over the underlying structure, and the artist's interest was actually stronger in what lay underneath. Indeed, in subsequent years the objects that had first shown up in these Expressionist thickets—such as pinball machines, soda bottles, one-armed bandits, and food dishes—came pushing forward, embodied in a different set of formal concerns. About this transformation, Thiebaud has noted that he found himself "clarifying large areas" and moving towards "an isolation of the object and much more of an interest in ... objective painting."\ \ \ Then at the end of 1959 or so I began to be interested in a formal approach to composition. I'd been painting gumball machines, windows, counters, and at that point began to rework paintings into much more clearly identified objects. I tried to see if I could get an object to sit on a plane and really be very clear about it. I picked things like pies and cakes—things based upon simple shapes like triangles and circles—and tried to orchestrate them.\ \ \ Thiebaud's paintings of food and consumer goods, which first emerged in mature form in 1961-62, have become such a familiar part of our art historical landscape that the risks they first posed can easily be taken for granted. As already seen, the inclination towards depictions of commonplace objects from middle-class America—decidedly "blue collar" subjects in the hierarchies of still-life painting—began to emerge for Thiebaud in the mid-1950s, well before the romance with similar iconographies that characterized the Pop movement. Thiebaud's choices may gesture backwards to such precedents as Stuart Davis's Odol bottle, Gerald Murphy's safety razor, or even Marcel Duchamp's urinal, but they mostly embrace objects that happened to be close at hand and that impressed him as interesting in character or presence. Also important in this development was his experience in advertising design and, for example, his layouts of simple objects in drugstore ads.\ It was the cafeteria-type foods, of course, the cakes, pies, ice creams, hamburgers, hotdogs, canapés, club sandwiches, and other staples of the American diet—all of which have a stereotypical this-can-be-found-anywhere-in-the-country-but-only-in-this-country quality—that brought Thiebaud most of his early notoriety. He described the almost giddy feelings he experienced with his first daring paintings of these subjects:\ \ \ When I painted the first row of pies, I can remember sitting and laughing—sort of a silly relief—"Now I have flipped out!" The one thing that allowed me to do that was having been a cartoonist. I did one and thought, "That's really crazy, but no one is going to look at these things anyway, so what the heck."\ \ \ With this concentration on simple objects or groups of objects came simultaneously a much clarified means of representation—the "isolation of the object" and "interest in objective painting" to which Thiebaud had referred—the rapid development of which can be traced by comparing the Oakland Museum of California's fine Delicatessen Counter of 1961 (fig. 4) with the Delicatessen Counter from 1962 in the Menil Collection (cat. 14).\ Already by the time of the earlier work, Thiebaud was pressing his subjects forward against the picture plane, simplifying the objects into basic formal units, and aligning them in strictly ordered progressions. A possibly coincidental relationship exists here with the comparably architectonic ordering principles seen in work by the turn-of-the-century American Realist John Peto (fig. 5), with whom Thiebaud also shares a love of vernacular objects. Undoubtedly more direct was the influence of still-life paintings by Giorgio Morandi, long admired by Thiebaud for their contemplative quiet, the palpable sense of protracted looking that they convey, and their delicate, varied effects achieved with seemingly minimal means (fig. 6). Not only is the basic organizational structure of such works germane to Thiebaud's paintings, but also their use of modulated light and discrete, slow-moving strokes to model the forms.\ Between the two delicatessen paintings under consideration, a process of even greater rationalization took place. In the Oakland Museum's picture, the alignment of forms is not as rigid as it would soon become The positioning of the different objects—the trays, containers, and cheeses—is still slightly loose, the countertop and bottom of the counter's window are angled slightly downward as they cross the picture plane, and the definition of individual shapes is somewhat rough and irregular. By the time of the Menil painting, these relationships had tightened considerably. The shelves and counters reach out now to grip the sides of the painting, forming a resolute, Mondrian-like grid. (Perhaps "Mondrian of the cake shops" is an equally valid epithet!) The brushwork is highly viscous but individual forms are nevertheless defined with increased clarity, and the colors also have brightened compared to the slightly grayed palette in the Oakland example.\ This signature style of Thiebaud's paint handling—the rich, smooth dragging of paint across a surface or around a shape in a way that both proclaims the luscious texture of oils and often transforms itself into the very material being depicted, from frosting or whipped cream to metal—is referred to by the artist as "object transference." Its origins can be traced not just to Morandi but also Thiebaud's interest in the bravura effects of such artists as Joaquín Sorolla (fig. 7), clearly apparent in the transitional Beach Boys of 1959 (cat. 4), the work of Willem de Kooning, and the Bay Area Figurative painters Richard Diebenkorn and David Park. Thiebaud's mature style had crystallized rapidly. The enthusiasm that greeted his still lifes when exhibited in New York at the Allan Stone Gallery in the spring of 1962 and later that year in San Francisco at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum reflect their strength and appeal (fig. 8).\ A great deal has been written about the possible meanings these still-life subjects held for Thiebaud beyond their purely visual delights and the problems in formal composition that they posed, though Thiebaud himself has warned against reading too much into their symbolism. "The symbolic aspect of my work is always confusing to me—it's never been clear in my mind.... I tend to view the subject matter without trying to be too opaque with respect to its symbolic reference, mostly from the standpoint of problematic attractions—what certain aspects of form offer." Nevertheless, he has also indicated that the foods he returned to again and again did hold an emotional or poetic resonance relating to the demotic Americanism of his boyhood memories. These paintings were made from memory, from mental images, not from actual setups of food or other objects:\ \ \ Most of [the objects] are fragments of actual experience. For instance, I would really think of the bakery counter, of the way the counter was lit, where the pies were placed, but I wanted just a piece of the experience. From when I worked in restaurants, I can remember seeing rows of pies, or a tin of pie with one piece out of it and one pie sitting beside it. Those little vedute in fragmented circumstances were always poetic to me.\ \ \ Thiebaud has also pointed out many times that his foods were always processed and prepared, not raw, "which mostly ... has to do with some sort of ritualistic preoccupation ... that interest in the way we ritualize the food, play around with it."\ Thiebaud's personal associations with the objects in his paintings, part of the personal voice he has spoken of trying to attain and open to others, reflect back upon family picnics with tables full of home cooking, his work in restaurants and small stores, and the displays of food and consumer goods he admired in drugstores, bakeries, and hardware stores. Distinctly different from the imagery in Pop Art, which simultaneously draws upon and satirizes consumer society, mass production, and advertising, his work relates an honest, Thornton Wilderesque appreciation for aspects of American experience that for decades have slowly disappeared:\ \ \ [My subject matter] was a genuine sort of experience that came out of my life, particularly the American world in which I was privileged to be. It just seemed to be the most genuine thing which I had done.\ \ \ Thiebaud's language can be decidedly low-key and limited in its formal agendas, but even then, his objects say a lot about the people who make them and enjoy them. They also comment on the abundance that is part of American society and the longing or desires that go with it: desserts lined up in rows stretching far into the distance like trees in a landscape but held separate from the viewer by the glass of window or case. The tone, however, is celebratory, not negative.\ \ \ Commonplace objects are constantly changing, and when I paint the ones I remember, I am like Chardin tattling on what we were. The pies, for example, we now see are not going to be around forever. We are merely used to the idea that things do not change.\ \ \ Unlike the Pop artists, irony was not one of his strategies.\ How much did Thiebaud know of these contemporaneous developments in New York when he began his series of still-life paintings? Magazines in the early 1960s kept him aware of the work of most of the artists loosely joined in this movement, and while he admired the paintings of Jasper Johns in particular and also the work of Claes Oldenburg, the graphic stylizations of others who aped the languages of commercial art left him cold. "I really wasn't interested in what they were doing," he has said. "I had too much respect for commercial artists. I appreciated how skilled they really are." At any rate, Thiebaud's homespun iconographies were actually born in paintings executed as early as the mid-1950s, well before Warhol, Lichtenstein, and others adopted similar subject matter.\ Thiebaud's fondness for objects could sometimes verge on the sentimental, as with certain charming paintings of trinkets or goofy toys and cakes. The rigorous process of construction to which he subjects his imagery, however, generally counteracts tendencies in this direction. In this way, he stands sentiment on its head, as in the masterful Toy Counter of 1962 (cat. 21), in which the disarming collection of cuddly teddy bears takes on a slightly sinister note through the forceful structuring of the composition into compartments that have a confining, cagelike quality. Thiebaud thinks of each picture very much as a problem in form: How can a given subject be most fully realized within the demands of its particular pictorial context, in a way that does justice to its own character or "thingness" and that gives it a confident structure that will hold up over time? He has noted about Realism that an artist "can enliven a construct of paint by doing any number of manipulations and additions to what he sees," which makes it possible for representational art to be "both abstract and real simultaneously."\ Thiebaud approaches these "constructs" as basic formal units, to be integrated and related in a clear dialogue that draws to a surprising degree on the abstract worlds created by such artists as Malevich and Mondrian with their tersely geometric concordances. In a composition such as Pastel Scatter (fig. 9), where the sticks of pastel seem randomly strewn across, the surface, we can actually see at work a structural principle of geometric organization not at all unlike ones made famous by the Dutch De stijl artist Bart van der Leck (fig. 10). Rather than abstract blocks of color, Thiebaud deals in recognizable objects that he has considerably simplified. In his well-known painting of Five Hot Dogs (cat. 8), each sandwich, slightly different from the others in color, shape, and angle of placement, not only provides an emphatic notation on popular culture, but also plays a part in the choreographic give-and-take between regimentation and variation. The ground plane is indicated by a thickly brushed layer of white pigment and is solid enough to accept the shadows created by a strong light, but, on the other hand, it seems to dissolve into nothingness like the brushy white spaces in one of Malevich's Surprematist paintings of the cosmos. Thiebaud noted that he was interested in the possibilities of the background forming both negative and positive spaces simultaneously so that "form both emerges from and is part of the background," which becomes "both flat and planar-metrically illusionistic ..., projecting or recessing, and even sometimes alternating, depending on your perception." The frontal screens in Four Pinball Machines (cat. 17) pay homage directly to geometric abstraction. In place of the normal advertising and scoring readouts, we find totally nonobjective patterns of grids and concentric squares and circles.\ Or consider the equally well-known Three Machines from 1963 (cat. 33). The glass globes here are wire-thin halos bursting with the densely packed round atoms of color inside. Barnett Newman told Thiebaud when he first saw one of these works displayed in New York that he thought they represented a truly American idea: "All those globes of colored beauty, and for a penny, out comes something sweet and wonderful!" The machines are modeled with deft, form-giving brushstrokes and variations of hue and value that imply three-dimensionality, but they appear coequally as cutouts flattened at calculated intervals across the picture plane. The whites of the background and what we presume to be a countertop and front are closely matched so that these three rectangles lock vertically into a flat screen that moves both back in space and forward. Also typical of Thiebaud's working methods are the juxtapositions of warm and cool tones and outlining of shapes or edges with lines that are divided into two or three different colors, intensifying color and producing that vibration of contour that has come to be known in his paintings as halation. These lines started as a kind of accident but later were used with full understanding of their relation to color theory and the laws of simultaneous contrast and take on a vivid life of their own. In Thiebaud's working out of formal problems, tangible reality and abstraction intermix as one.\ While the first exhibitions of Thiebaud's pies and cakes and other food paintings at the Artists Cooperative Gallery in Sacramento and the Arts Unlimited Gallery in San Francisco in 1961 drew little attention from critics or collectors, his first show at the Allan Stone Gallery in New York in 1962 was a huge success, marking the beginning of a close relationship between the artist and dealer that has lasted until today. The exhibition sold out, with numerous museums and prominent collectors acquiring works and accolades rapidly appearing in several national publications. The degree of the response, a bit overwhelming for Thiebaud, was due in part to the automatic associations made by many with the burgeoning Pop movement. It encouraged him, nevertheless, to further explore the stylistic directions newly opening. A number of ambitiously scaled still-life paintings date from 1962-63 (for example cat. 13, 17, 18, 25, 26, 28), and Thiebaud continued to work on still-life themes for the rest of the decade and, indeed, periodically ever since, spiraling back to this subject as he has to other favorite themes throughout his lengthy career.\ In general, the still lifes from later years followed familiar stylistic paths, reinterpreting earlier motifs and also introducing a number of new subjects, including piles of books, brightly colored ties (cat. 57), eyeglasses, and paint cans. Most often light in mood, these works could, however, suddenly turn dark. A group of particularly lugubrious compositions date from around 1983-84, including Black Shoes and Dark Candy Apples (cat. 74). In the former, a pair of worn dress shoes that invoke Van Gogh's famous, highly autobiographical Pair of Shoes stand symbolically for the artist himself, casting him in an uncharacteristically melancholic light. Thiebaud's Pinned Rose of 1984 (fig. 11) is especially funereal, and his Boxed Rose, also from 1984 (cat. 76), is a simultaneously grim and attractive analogue for a body in a casket. Similar images threaded their way into Thiebaud's development from time to time, contributing a chill to the usually warm emotional temperature of his work.\ Not long after the triumph of his New York show of 1962, Thiebaud changed direction and began to aggressively tackle a relatively new subject, the human figure. He had always found the figure challenging, calling it the most fundamental and also the most difficult art theme. This reordering of thematic priorities came as a needed break from the still lifes, though it also undoubtedly reflected the influence of the Bay Area Figurative movement championed by David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, and others, with which Thiebaud was familiar since the mid-1950s:\ \ \ Actually, while I was doing still lifes I was at the same time trying to do figures, but very unsuccessfully. I was doing them concurrent with my food paintings in 1962, but in 1963 I decided to concentrate on figures for a while. I think an artist's capacity to handle the figure is a great test of his abilities.\ \ \ In many ways, the figure paintings are direct extensions of the still lifes. In both cases, Thiebaud attempted to objectify as fully as possible the basic subject. He situated figures in the same abstract, open spaces that engulfed the still lifes, flooding them with the same intense illumination, and constructing them with a similar materiality of paint. When joined in combinations, they display a regimented seriality like that commonly found in the still lifes. Revue Girl from 1963 and Five Seated Figures from 1965 provide good examples (cat. 35, 44). In the former, the stiffly posed entertainer is personally remote and slightly unreal, analyzed as substance, color, and light, and lacking the inner voice that makes the show girls of Walt Kuhn, an obvious precedent, such emotionally ambivalent representatives of their trade (fig. 12). Thiebaud presents his entertainer, however, with so much obvious delight in the basic act of painting that we do not begrudge the missing personality. Thickly applied strokes push and pull around her contours, giving her a decidedly sculptural presence. High-keyed colors, intensified by the lighting, become even stronger through reinforcing combinations, such as blues dragged through whites for a Sargent-like brilliance, or reds and greens woven together in surrounding outlines. The figure's simple, frontal placement contrasts with the opulence of her painterly realization. We are not far from the treatment of objects in such luscious still-life paintings of the era as Around the Cake (cat. 11).\ Still-life precedents also come to mind when Thiebaud's figures are multiplied, as in his Five Seated Figures. Typically, a basic pose is repeated and permutated in much the same way that a piece of pie or cake is examined from different angles in one of the many paintings of bakery displays.\ In a big difference from the still lifes, the figures are almost always painted from models, not memory. Thiebaud has frequently commented on how difficult he finds this task, and how hard it is to note, absorb, filter, and reconstitute the complex information that comes from a close study of the human form:\ \ \ I started out painting the figure from memory, with disastrous results. I just didn't know enough about the figure and still don't. It's very difficult for me. So I have people pose, and I just keep on trying.\ \ \ In these paintings, he looks for static and neutral poses that tell nothing about the sitter. He strips figures down to the essential details and eliminates settings: rarely is an object or attribute included that might add narrative interest. As one author put it, Thiebaud insists on "limiting the figure to itself, its own objectness. [Just] the facts, please." This effort to avoid expressiveness can often yield an effect of mute isolation that in itself becomes expressive. In this regard, comparisons have been made between his figures and those of Edward Hopper, an artist Thiebaud greatly admires. Man in a Blue Chair from 1964 (fig. 13), for example, can be compared in spiritual as well as formal terms with the woman in Hopper's Morning Sun of 1952 (fig. 14). Certainly they share the same sense of lonely introspection, even if Hopper tells us much more about his subject's personal situation. Another less commonly recognized analogy for such works exists with the portraits and figure studies by Thomas Eakins. Both the basic pose and moody, rather sullen expression in Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book from 1965-69 (cat. 54) call to mind Eakins's Miss Amelia Van Buren (fig. 15). And several of Thiebaud's studies of men, including the Standing Man of 1964 (fig. 16), relate at least distantly to such works by Eakins as The Thinker (fig. 17). In the latter comparison, the neutrality of the setting in both cases focuses attention on the stiff immobility of the figure and the inner concentration highlighted by each man's knit brow. Through Hopper and Eakins a line is drawn to other nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century artists concerned with the lack of human mutuality and communication as a theme of modern life.\ Clearly, many of Thiebaud's figures—including such colorful icons of the 1960s as Revue Girl and Girl with Ice Cream Cone (cat. 32)—do not share these properties, although the chic of the Girl in White Boots (cat. 41) fits easily enough with the sense of deep reverie she projects. To some degree the expressive qualities alluded to are by-products of other of Thiebaud's artistic intentions, but the prototypes provided by the work of such favored artists as Hopper and Eakins must have played a role. Perhaps even more to the point are the formal similarities with Hollywood publicity photographs of the type that Thiebaud himself helped to produce while working for Universal-International Studios as a poster artist and layout designer in the late 1940s. The altered state of reality in such works (fig. 18), created by the spatial isolation of the figure, the strong side-lighting, and the frozen poses and facial expressions, is strikingly similar to the staged effects in many of Thiebaud's figural essays.\ Still-life paintings and figure studies continued to alternate in Thiebaud's oeuvre through the remainder of the 1960s, but towards the end of the decade he shifted focus again to yet another theme, the rural landscape. Embodied in one way or another—as direct plein-air studies, modern cityscapes, or grand, formalized panoramas—the landscape theme remained basic to his art and recirculated through his development from that time onward.\ Thiebaud painted a number of beach scenes in the 1950s and early 1960s (cat. 4, 30), and starting around 1963 he produced a series of small, richly brushed landscape studies, such as the beautiful Hillside of 1963 (cat. 29), that extend into nature the stylistic terms of the contemporaneous still lifes. In the rural landscapes that began to emerge around 1966-67 a stylistic shift took place (cat. 50-52). Often worked up from small studies drawn or painted in situ, these large-scale compositions display an odd assortment of geological features—steep ridges, bulging cliffs, balloonlike lakes, and solid, confectionary clouds—generally presented in flattened, abstracted formats. Many have a cartoonish quality, replete with miniature trees, buildings, and animals, but as strange or fanciful as they might seem, they are grounded in fact. As Thiebaud has explained:\ \ \ [One critic] thought, as many people think, that they're invented forms, that they're esoteric, or even arcane surrealists' references; but they're not that at all. They're painted right on the spot. I think people aren't used to seeing things cut from corner to corner so rudely or crudely, and maybe it's upsetting or seems unfulfilled in the sense of space. It's something, nonetheless, that fascinates me. It came about by driving across the country and actually going through those canyons. Those imposing structures seem to just fall in on you and make such a nice visual shape that I can't resist doing them.\ (Continues...)

Preface7Acknowledgments8Unbalancing Acts: Wayne Thiebaud Reconsidered11An American Painter39Wayne Thiebaud: A Paintings Retrospective, Catalogue of Works71Chronology191Selected Solo Exhibitions 1985-1999205Selected Group Exhibitions 1985-1999207Selected Bibliography 1985-1999211Index to Illustrations of Wayne Thiebaud's Works215

\ Publishers Weekly - Publisher's Weekly\ "He is an American painter, someone who paints for a living and whose subject, for all its formal perfection, is what we are to make of American abundance," writes New Yorker art critic Gopnik in his long, in-jokey introductory essay to Thiebaud's oeuvre now touring the country as a retrospective. As Gopnik makes clear, Thiebaud is famous for his lush early '60s paintings of cakes, other sweets and people eating them, but this book and the exhibition it documents--put together by chief curator Nash of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, who also provides an essay--reveal the painter to be preoccupied with a larger slice of American life. The impossible perspectives and multigraded blues and yellows of the cityscapes here seem more bizarrely true to San Francisco than stills from Vertigo. Heavy Traffic, Deli Bowls, Tie Rack and Rabbit are just what they say they are, yet their surfaces coax us into looking at them harder and longer than such banal objects could possibly entice on their own. Such dressings-up themselves are commonplace in media-saturated American life, and Thiebaud redirects their energy unerringly throughout the 160 illustrations here, most in color. One might wish for a less insidery guide to the work than Gopnik's, but the panache of his biographical prose carries readers right into the paintings, well and comprehensively selected by Nash, whose own essay provides welcome detail on Thiebaud's working life. (Aug.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalA retrospective exhibition of paintings by Thiebaud, the contemporary California artist best known for his images of cakes and delicatessen displays, will appear in San Francisco, Fort Worth, Washington, DC, and New York next year. This exhibition catalog provides an excellent overview of Thiebaud's long painting career, including his most recent turn in the 1990s to rural landscape views. The essays by Nash, a curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and Gopnik, an art and culture writer for The New Yorker, provide basic biographical information and place Thiebaud's work in the context of 20th-century art. This book is a significant addition to contemporary art literature and is suitable for both interested lay readers and specialists in the field.--Kathryn Wekselman, M.Ln., Cincinnati, OH Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\ \