Winging It: A Memoir of Caring for a Vengeful Parrot Who's Determined to Kill Me

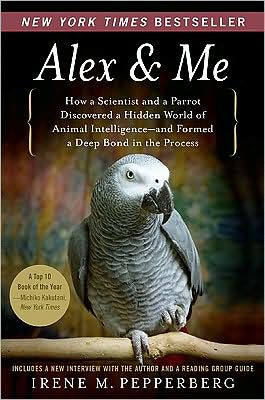

A gift from an overseas relative, Graycie, an African Gray parrot, arrives in the Gardiner home not long after the birth of their first child, adding the responsibilities of parrot-hood to their newfound parenthood. Jenny Gardiner and her husband were hoping for a docile, beautifully plumed, Polly-want-a-cracker type of companion—but patchily feathered, scrawny, ill-tempered Graycie was the furthest thing from what they envisioned..\ In Winging It , Gardiner shares in vivid and hilarious...

Search in google:

A hilarious and poignant cautionary tale about two very different types of creatures, thrown together by fate, who learn to make the best of a challenging situation — feather by feather.Like many new bird owners, Jenny and Scott Gardiner hoped for a smart, talkative, friendly companion. Instead, as they took on the unexpected task of raising a curmudgeonly wild African gray parrot and a newborn, they learned an important lesson: parrothood is way harder than parenthood.A gift from Scott's brother who was living in Zaire, Graycie arrived scrawny, pissed-off, and missing a lot of her feathers — definitely not the Polly-wants-a-cracker type the Gardiners anticipated. Every day became a constant game of chicken with a bird that would do anything to ruffle their feathers. The old adage about not biting the hand that feeds you — literally — never applied to Graycie.But Jenny and Scott learned to adapt as the family grew to three children, a menagerie of dogs and cats, and, of course, Graycie. In this laugh-out-loud funny and touching memoir, Jenny vividly shares the many hazards of parrot ownership, from the endless avian latrine duty and the joyful day the bird learned to mimic the sound of the smoke detector, to the multiple ways a beak can pierce human flesh. Graycie is a court jester, a karaoke partner, an unusual audio record of their family history, and, at times, a nemesis. But most of all, she has taught the family volumes about tolerance, going with the flow, and realizing that you can no sooner make your child fit into a mold than you can turn a wild parrot into a docile house pet. Winging It is an utterly engrossing reminder of the importance of patience, loyalty, and humor when it comes to dealing with even the most unpleasant members of the family. Library Journal Initially delighted when she and her husband unexpectedly received an African gray, Gardiner finds that her fantasies of a docile, loving bird are quickly dashed with the wild-born and tenacious Graycie. Gardiner chronicles how two frazzled but committed parents raised this obstinate bird over the span of 20 years along with three children and a menagerie of dogs and cats. VERDICT Often comical and sometimes tragic but never dull, Gardiner's memoir proves that the hope of having a model pet (or child) is usually not realistic. It will speak to animal lovers and offer fair warning to anyone considering the 40-year-plus commitment of owning a parrot.—Judy Brink-Drescher, Molloy Coll., Rockville Centre, NY

\ The Man in the Yellow Hat\ “Look. Don’t blame me because you were kidnapped from the jungles of Africa.”\ This sounds like something the man in the yellow hat might say to Curious George. But in my case, it’s a mantra. Something I repeat daily—sometimes ten, fifteen times—to Gracyie. In fact, it’s a wonder she doesn’t repeat it back to me.\ Graycie has been a member of our family, albeit a reluctant one, for over nineteen years. She was a gift from my brother-in-law. A gift, I’m fond of saying, that keeps on giving.\ Our African gray came to us at Christmas in 1990, shortly after we’d moved into our very first home in Springfield, Virginia, a bedroom community of Washington, D.C., four months after the birth of our first child, who was still waking every two to three hours at night, thereby assuring a personal mental incoherency unmatched since. This was back when we were still cloaked in the stupor of new parenthood, bleary-eyed and sleepless, unable to get a handle on one needy two-legged individual who counted upon us for virtually everything, and suddenly we found ourselves with yet another. Only this one had beady gray eyes, a beak that could snap my finger off, and a wingspan that would eventually extend a full eighteen inches.\ It’s not that we didn’t want Graycie. We did. But as parents of a newborn, we were already wondering if we could trade in the exhausting baby for a pretrained child with good posture and even better manners. We couldn’t deal with the parrot starter kit that would require multiple all-nighters for assembly: we wanted this sucker neat, sweet, and ready to tweet. We needed a maintenance-free bird—one that would regale us with its uncanny mimicry and not make too much of a mess. I realize now that this is like expecting a baby who never cries.\ We probably owe our fascination with parrots to my husband’s childhood in Rio de Janeiro. Scott lived with his sister Laurie, brother Mark, and parents Mia and Keith in Brazil for several years after his father’s job took him to South America in the late 1960s. While there, Mark got a green Amazon parrot for his thirteenth birthday. Mengo was a beloved family pet whose untimely demise prompted Mark to stuff the thing and mount him so he could be perpetually remembered. Now we live in central Virginia, outside a small city that is surrounded by plenty of quiet countryside. Because of that rural influence and commensurate hunting culture, it’s not at all uncommon to encounter all sorts of dead critters on display in folks’ homes: deer, squirrels, rabbits, even the occasional bear. But I think I can safely assume that Mark’s visitors routinely did a double take upon encountering the corpse of his soulless parrot staring down at them from the wall of his D.C.-area home, back when the cadaver used to be on public display.\ I suppose I came to the relationship with a modest interest in parrots thanks to my uncle Bill, who bred parrots years ago and had raised a stunning aquamarine-colored macaw from an egg. This parrot was imprinted from birth by my uncle, and despite his imposing size—macaws can grow to be a foot and a half long with a nearly four-foot wingspan—was an extraordinarily gentle creature. Billy took that bird with him everywhere: to the retail store he managed, on joyrides in his convertible, on the golf course. He loved it as if it was his child, and the bird reciprocated those feelings: Billy was its father, for all intents and purposes.\ So perhaps when Scott and I ended up together, we were both just curious enough about parrots that it was inevitable that, with the help of one generous relative, a feathered friend (or foe) was in our future.\ Scott and I met through mutual friends while undergraduates at Penn State. We were dating other people at the time and didn’t start going out until we were both living in the D.C. area the year after we graduated. I was working on Capitol Hill as an assistant press secretary for a U.S. senator, and he was working for a federal government contractor for the Agency for International Development. Before we actually started dating, we’d run into each other at social functions all the time and say, “Hey, we should get together sometime!” But each time we set something up one or the other of us would cancel plans at the last minute. Such was the lifestyle of young professionals in D.C. When we finally got together we realized all we had in common; we couldn’t figure out what took us so long.\ Early on in our relationship I realized that Scott hailed from a pet-friendly family. When I encountered the menagerie of crea tures at his parents’ home, where he was living when we first started dating, it included two old and smelly golden retrievers and a couple of cats. Then I met his brother’s latest venture in parrothood: some type of green Amazon parrot named Plato who had the personality of Sheetrock and entertained no plans of talking. Plato was best known for cowering and trembling in a corner of his cage. He did not talk, coo, growl, chirp, whistle, or sing. He simply existed. Oh, and crapped a lot.\ Meanwhile, I was living with my sorority sister and good friend Tammy in Alexandria while working on the Hill. We had a fabulous time rooming together, occasionally threw amazing parties, and greatly enjoyed our yuppie lifestyle. But after over a year of dating it became apparent that it made more sense for me to move closer to Scott, who’d moved in with his two best friends in Arlington. When I wasn’t at work, I was spending my free time at his place, and my costly condo rent on a very meager congressional staffer’s salary didn’t do my wallet any favors. It didn’t take me long to relocate. I learned that a room had become available in a group house where Mark lived, just minutes from Scott’s town house. The house was cozy, cheap, and a quick commute into the city, so I jumped at the chance to move in; once I became pseudo roommates with Scott’s brother (he lived in the basement in a separate unit), I got to spend plenty of time around Mark’s parrot.\ Each morning as he left for work, Mark would turn on a parrot training tape for Plato’s education/entertainment. Poor Plato got to listen to that tape, on which Mark had recorded two words on an endless loop, for hours. Even I got sick of hearing “pretty bird” as the words drifted up through the air ducts, and to this day I can still hear Mark’s voice ringing in my head saying that mind-numbing phrase.\ I’m fairly certain that Plato had been driven insane by the time he moved in with Scott and Mark’s parents when Mark moved to Africa to work in the embassy in Zaire a couple of years later. And when Mark eventually got married, Plato—still alive, but without much of a life—was soon relegated to Mark’s isolated upstairs office, where he was left to keep company with Mengo, high atop his death perch. Of course Mark was very fond of Plato, but after a while, what do you do with a scared bird who won’t come out of his cage?\ The icing on our parrot-shaped cake came a year or two later when Scott’s parents celebrated their thirtieth anniversary by taking the family (by then Scott and I had married) to the Caribbean to sail on a hand-hewn schooner, skippered by a prototypically bearded captain named Ed and crewed by a sleek white cat and a yellow-naped parrot with the improbable name of Barnacle Bill, who did a damn good job of replacing a television in our lives during that week on the high seas.\ No better or simpler amusement can be found than being in the company of a gregarious parrot. I think the sheer unexpectedness of conversation from a lipless creature enhances the entertainment factor. Barnacle Bill had the requisite parrot patter that any seagoing parrot worth his salt could say: Yo, ho, ho and a bottle of rum, Polly wanna cracker, and the like. But his repertoire reached far beyond the basics. He had us all in hysterics as he repeatedly sang “A Pirate’s Life for Me” and the refrain from “So Long, Farewell” from The Sound of Music, complete with the Doo-doodle-doo-doo-doo-doo-doo, doo-doodle-doo-doo-doo-doo. (I admit it. I filched the idea from Captain Ed.)\ Captivated, we simply had to have a parrot. Scott and I were like young newlyweds upon seeing a tender baby sleeping peacefully in a mother’s arms. “Oh, how sweet,” we said. “We definitely need one!”\ Those words would come back to haunt us. Upon returning from Mia and Keith’s anniversary trip, I set out to buy my husband his very own parrot for his birthday. Back then, unsavory merchants conducted a steady trade in wild-caught parrots, and only the really ethical vendors went to the trouble of breeding parrots domestically (though unfortunately today parrot mills are common). Raising birds from eggs is tough work. In fact, not too long ago they could only determine the sex of birds surgically, so it was a bit of a project even to impregnate a parrot. Once hatched, infant birds have to be fed practically hourly by dropper. If you think a newborn baby is hard to keep alive, just think about nursing a scrawny, naked, defenseless little parrot.\ So I researched the big purchase and found I could get an imported bird for roughly the price of a really expensive dinner out, which worked with my limited budget but not with my morals. I couldn’t have it on my head that I’d contributed to the demise of a species, as these inexpensive birds were caught en masse by poachers who clear-cut trees in the jungle to get baby birds still in their nests. The mortality rate was high, as was the suffering: birds by the hundreds would be jammed into small crates with little food or water, ultimately bound for clueless consumers in the United States who, like us, wanted an amusing pet.\ Well, I couldn’t support that. I’d have no part in gratuitous cruelty for the sake of the almighty buck. Alas, there was no budget for a hand-raised parrot, which would cost roughly the same price as our week in the Caribbean.\ So instead, we got a dog.\ Unbeknownst to us, there was still to be a parrot in our future. Just not quite the type of parrot we had envisioned.\ © 2010 Jenny Gardiner

\ Library JournalInitially delighted when she and her husband unexpectedly received an African gray, Gardiner finds that her fantasies of a docile, loving bird are quickly dashed with the wild-born and tenacious Graycie. Gardiner chronicles how two frazzled but committed parents raised this obstinate bird over the span of 20 years along with three children and a menagerie of dogs and cats. VERDICT Often comical and sometimes tragic but never dull, Gardiner's memoir proves that the hope of having a model pet (or child) is usually not realistic. It will speak to animal lovers and offer fair warning to anyone considering the 40-year-plus commitment of owning a parrot.—Judy Brink-Drescher, Molloy Coll., Rockville Centre, NY\ \