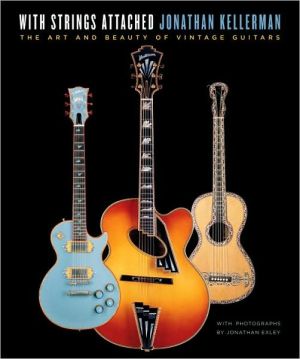

With Strings Attached: The Art and Beauty of Vintage Guitars

For thirty-five years, bestselling author and accomplished musician Jonathan Kellerman has been, as he puts it in his Introduction to this lavishly illustrated, endlessly fascinating volume, “chasing fabulous sound.” The result of that quest is a world-class collection of guitars, mandolins, and other stringed instruments that number more than 120 . . . and counting.\ Kellerman takes us on a fascinating guided tour through his collection, complete with rich personal histories of his favorite...

Search in google:

For thirty-five years, bestselling author and accomplished musician Jonathan Kellerman has been, as he puts it in his Introduction to this lavishly illustrated, endlessly fascinating volume, “chasing fabulous sound.” The result of that quest is a world-class collection of guitars, mandolins, and other stringed instruments that number more than 120 . . . and counting.Kellerman takes us on a fascinating guided tour through his collection, complete with rich personal histories of his favorite instruments and of the brilliant, often eccentric craftsmen and musicians who brought them to life. It is a record of one man’s lifelong love affair with the guitar . . . and it is much, much more.Whether writing about household names such as Fender, Gibson, Martin, and Dobro or about marques revered by aficionados–D’Angelico, Hauser, Stromberg, and Torres–Kellerman brings to bear the same sure storytelling instincts and keen attention to detail that characterize his bestselling fiction, making each entry a sparkling mini-essay as much to be savored as the sensual photographs that follow.Your fingers won’t be walking through With Strings Attached. They’ll be strumming. Picking. Stroking.And dancing.

The Power of Love\ I’m the oldest of three siblings. Several years ago, I asked my mother why she was so much stricter with me than with my sister and brother.\ Mom thought for a while, then she said, "You took all the fight out of me."\ \ Bayside, New York, Spring 1958\ Mom: Jonathan, you’re eight. It’s time you learned to play an instrument.\ Me: Okay.\ Mom: You should study the violin.\ Me: I want to play guitar.\ (Long pause)\ Mom: The violin’s the most beautiful instrument in the world. Don’t you remember those Jascha Heifetz records I played for you?\ Me: I want to play the guitar.\ Mom: Your Uncle Aaron plays the violin. He gets so much enjoyment out of it.\ Me: Uncle Jack plays the concertina. So what? I want to play the guitar.\ (Longer pause)\ Mom: Why the guitar?\ Me: I like it.\ Mom: So start with the violin. It’s harder than the guitar and after you master it, you can try the guitar.\ Me: I want to play the guitar.\ \ Bayside, New York, Summer 1958\ I begin my first guitar lesson with Mr. Thomas D’Agostino, a stern, adept jazzman who’d clearly rather be gigging at a club than teaching me.\ My instrument is a flat—back, all—black, World War II—era, no—name Gibson archtop picked up by my beloved violin—playing Uncle Aaron at a Lower East Side pawnshop for fifty bucks. The strings are Black Diamond steels of a gauge sufficient to strut the George Washington Bridge. My hands are barely able to reach around a neck that feels like an ax handle. I practice for an hour every day, learning to sight—read, keeping time with a metronome, wincing at the pain that sears through my not—yet—callused fingertips.\ I struggle with scales. Strain to learn chords. Occasionally, I’m able to finger notes without setting off discordant buzzes. Barre chords are far beyond my stretch. F major becomes a dreaded enemy.\ Finally, after several weeks, I’m allowed by Mr. D. to venture into the musical wilderness, clunking my way through "Skip to My Lou," "Red River Valley," "La Paloma."\ I am nine years old. Bored, distracted, aching, plagued with self—doubt about this torturous process that I have initiated.\ Happy.\ I’m old enough to have grown up with the radio. Much as kids today browse cyberspace, a good deal of my spare time from the age of three on involved twirling the dial of an old Philco the size of a refrigerator. My dad worked two jobs and my mom was busy raising my sibs. Anything that kept me out of their hair was welcome.\ Hours of audio -exploration took me interesting places, creating an open—minded approach to music that has remained with me. Genres mean nothing; I can appreciate anything from opera to gagaku to rap, as long as it’s -done well.\ But one unifying factor has typified my favorite music since toddlerhood: I am entranced by the guitar.\ Such primal passion is probably rooted in the less-developed centers of the brain and cannot be explained rationally. I will not try. Suffice it to say that my chancing upon Andres Segovia’s rendition of a Bach bourre on a static—marred FM classical station was an epiphany—inducing experience. So was discovering Ram—n Montoya’s fiery flamenco work; Scotty Moore’s fingerpicked accompaniment of Elvis; the lush, strummed chords backing up Harry Belafonte’s calypso ballads; Leadbelly’s twelve—string runs.\ Then there was Santo and Johnny’s haunting "Sleepwalk," produced on an instrument that sounded so different: the steel guitar. As a fiftieth birthday present, I taught myself steel.\ I love all of it.\ By junior high we had moved to the West Coast and I was earning spending dough teaching other kids to play guitar and gigging in a bar -mitzvah/wedding combo, doubling on bass–not with a real bass; I turned down the tone control on my amp and faked.\ My instrument of necessity was a cheapo Japanese electric solidbody that viewed staying in tune as a joke. The tone it produced ranged from tinny to really tinny. Finally, in 1965, I saved enough cash to buy a better tool. A hundred and twenty-one dollars barely got me a ’62 Gibson Melody Maker at Wallach’s Music City, on the northwest corner of Sunset and Vine in Hollywood. Thirty dollars more would’ve earned a Les Paul.\ I schlepped my new acquisition home on the bus and gigged with it for years. It produced cool sound and the whammy bar was fun, but someone must’ve hexed the wiring; the damn thing would shock me at inopportune intervals. For acoustic noise, my old Gibson archtop continued to suffice. (I’ve held on to that one, after foolishly having it gussied up and refinished to sunburst during the seventies.)\ Married at twenty-two, equipped with a Ph.D. in clinical psychology at twenty-four, I began working with pediatric cancer patients at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles. High—stress days on the wards endowed nighttime guitar playing with new meaning. I taught myself jazz chords, finger-picking, and bluegrass ditties. I began saving up for a tuneful instrument and lucked out in 1975, when my supervisor offered me a never—played five-year-old Martin D-28 for the $325 it had cost him.\ Over the next decade, I fathered children, treated patients, trained physicians and psychologists, conducted research on behavioral medicine, and wrote two books on psychology. Evenings were spent augmenting my med school professor’s salary with private practice. The quiet hours between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. were spent in an unfinished garage, writing fiction no one wanted to publish.\ My wife, eerily prescient, had convinced me to buy a house in 1974, just before the California real estate boom, so we were in better shape than most of our friends. I began setting aside cash for a really great guitar.\ In 1978, I bought a D’Angelico New Yorker for eighteen hundred dollars and learned about a whole new level of sound.\ The following year, I bought a Stromberg Deluxe for eight hundred dollars and a Brazilian rosewood Martin D—35 for not much more. The year after that, a truly spectacular Stromberg Master 400 came my way for two grand. A 1924 Lloyd Loar—-signed L—5 was offered for the staggering sum of four thousand dollars and I declined. But my wife bought it for me.\ Those prices, ludicrous by today’s standards, strained our budget. Faye, a skilled musician herself, was content to play one mandolin, but she never held me back. Quite the contrary; as guitars began soaring in value, it was my brilliant, beautiful spouse, eerily prescient, who encouraged me to trade up before all the good stuff was out of reach.\ I began buying, selling, trading, and poring over instrument lists mailed out by vintage guitar dealers–a relatively nascent profession at the time.\ I studied want -ads and used my lunch hour at the hospital to track down interesting-sounding items. Ignorance, confusion, and flat—out larceny prevailed, and most of those detective jaunts ended in futility. But once in a while I struck gold.\ A hippie living in a Hollywood crash pad sold me his ’34 Gibson L—5, housed in a battered leather case festooned with international travel stickers, because he was going to meditate full—time and no longer needed "help."\ A prosperous Mexican—American businessman brought his late father’s glorious dead—mint 1940 Epiphone Emperor to my private office waiting room after hours, accepted my check with tears in his eyes, and told me he was happy someone would be playing it again.\ A stooped, half—blind, ninety-year-old man yanked open the creaky door to the spare bedroom of his mid-city apartment and revealed a ceiling—high mountain of instrument cases–trumpets, tubas, xylophones, zithers, violins, double -basses. Mostly junk, but there was that pearloid—decorated Vega archtop.\ A junket to a dusty, chain—linked, pit—bull—guarded trailer in an ominous section of Sunland introduced me to a huge mustachioed man who styled himself "the Assyrian Elvis." He sold me his 1937 Gibson Super 400 because he needed something flashier for his Vegas debut. I played that one for a couple of years, found it lacking in volume, and traded it, plus cash, for another D’Angelico.\ Guitar prices began soaring to inconceivable levels. My New Yorker was exchanged for a better—sounding version of the same model, now worth five thousand dollars.\ Then ten.\ Then twenty. And rising...\ In 1985, I published my first novel, When the Bough Breaks. The advance payment amounted to three bucks an hour. My main gig was seeing patients, so this was found money, right?\ I spent it on a guitar.\ To everyone’s surprise–most of all my publisher–the book became a best-seller.\ Hmm...\ I won’t insult your intelligence by claiming I never intended to build a collection, because you don’t just happen to end up with 120 guitars. But amassing and hoarding were never my primary motivations. For the past thirty-five years, I’ve been chasing fabulous sound. And since the guitar produces a more varied sound than any other instrument, the quest has led me to lots of guitars.\ The collector’s disease may be a variant of obsessive—compulsive disorder. It may also be rooted in gender: When women collect, the object of desire is often rational and utilitarian–something worn, used for adornment, taken out in public. Jewelry. Designer purses. Vintage clothing. The stuff that sits on shelves or in cases or hides in albums and drawers–coins, stamps, matchbooks, toy soldiers, watches, FabergŽ eggs, beer cans, paperclips–tends to be acquired by males. And being a manly sort...\ Enough cheap rationalization. I can’t explain the reasoning behind what you’re going to view in this book with any sense of logic, though I’ve always acquired with forethought and clear intention. And a desire to learn.\ The process of acquiring has involved a huge amount of self—education, allowing me to indulge another passion: research. The same fascination for details–okay, minutiae–that I indulge each time I sit down to write a new novel comes to play when I enter new areas of guitar history. Collecting guitars has taught me volumes about music, psychology, ethnography, acoustical physics, culture. And the monumental impact of the guitar upon all that.\ Most important, my instruments sound great and I love playing them. I hope you enjoy viewing them.\ Jonathan Kellerman