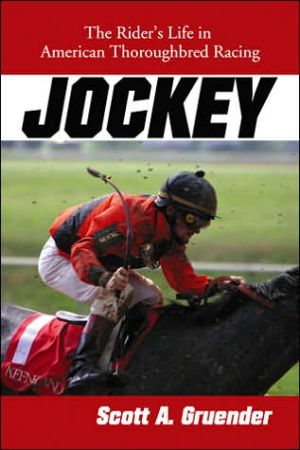

Yankee Doodle Dandy: The Life and Times of Tod Sloan

In the 1890s, feisty Tod Sloan (1874-1933) abandoned the centuries-old jockey tradition of riding in a straight sitting position and instead crouched low on the neck of his horse. The result was not only a string of victories for young Sloan but also a revolution in horse racing. In this entertaining book, award-winning author John Dizikes recounts the remarkable story of the Indiana boy who rose from obscurity to become the most famous jockey in the United States and Great Britain at the...

Search in google:

In the 1890s, when jockey Tod Sloan first assumed a low crouching position over the neck of his horse, he precipitated a revolution in horse racing. This entertaining book recounts the story of the feisty jockey, famed throughout the U.S. and Great Britain at the turn of the century. Award-winning author John Dizikes evokes the turbulent, colorful world of racing and gambling and in the process illuminates such topics as the lionizing (and demonizing) of celebrities and the democratization of sport. Washington Post - Jonathan Yardley Sloan's story is well worth telling and that John Dizikes tells it very well in Yankee Doodle Dandy....[H[is influence on his sport and on American culture was substantial and lasting. This first-rate book gives it, and him, all due credit.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ NAMES\ \ \ Names. Tod Sloan had a lot of names (and very little of anything else). His father, cruelly, called him "Toad" because he was so small. His real name, "that which I was christened by," was James Forman Sloan. There was a grander version, too, James Todhunter Sloan, which someone, "I forget who," hung on him. It turned out to be important because it was eventually shortened to Tod, the name everyone called him by. For a number of years he even had a different last name—Blauser—the name of the people who raised him as a boy.\ His upbringing was as random as his names, marked by the casual harshness of the lives of ordinary people of the time and place, Bunker Hill, Indiana, twelves miles from Kokomo, where he was born on August 10, 1874. Tod's father had moved there after serving in the northern army during the Civil War; and made his living as a barber and real estate agent, shaving his neighbors both ways. When Tod was five, his mother died. In his own book, Tod Sloan by Himself, written long after these events and far away from these places, he said nothing about it, other than to record it. And he said nothing about what happened to the rest of his family—he had two older brothers and a sister—after it occurred. He didn't even mention his mother's name or explain why he had been given to the Blausers. Maybe he didn't know. His history in these years, so obscure to us, may have been equally unknown to him.\ Tod Sloan by Himself is the source of most of what we know about his early years; its tone isnoncommittal about the stories put in, and the ones left out. It is matter-of-fact, offhand, poker-faced, "imperturbable as a gravestone," the style adopted by sportsmen of the time. In its pages the pains of childhood and youth are unrecalled, though very occasionally something deeper flashes out, as in the simple reference to being farmed out to the Blausers "when I was left alone by those I have never ceased to grieve for." A lament for the dead mother, surely, but also for the father who abandoned him? Anyway, that event fixed the pattern of how he perceived his relation to the world: a little guy, on his own, calculating the odds, taking his chances. Tod Sloan, alone, Tod Sloan, by himself.\ With the Blausers, however, Tod apparently lived a life that reflected one of the prevailing American cultural archetypes, that of a carefree childhood lived in harmony with nature. This idea, at least as old as the Greeks and Romans, had been given renewed vitality by the Romantic movement of the early nineteenth century, with its emphasis on the innocence of childhood as contrasted with the corruption of social institutions. It wasn't only Americans who invested nostalgic capital in this idea, but it flowered with special luxuriance in the United States because of the nation's recent experience of wilderness and frontier. In the 1870s and 1880s, when Tod was growing up, artists of all kinds illustrated this theme. Winslow Homer painted carefree children frolicking in the fields and meadows, released from captivity in the one-room schoolhouse. James Whitcomb Riley evoked this Hoosier idyll of blameless boys roaming the countryside and sharing innocent amusements. Thomas Bailey Aldrich's novel of 1888, The Story of a Bad Boy, was a bestseller. (He wasn't really bad, just mischievous.) This idyllic picture of childhood was only half the story, however. There was also a harshly antiromantic view. In a popular form it was to be found in George W. Pecks bestseller Peck's Bad Boy and His Pa. Hennery Peck, the boy, was mean-spirited and sometimes brutal in dealing with parents and peers. He was truly and naturally bad.\ Behind and well beyond the imaginative grasp of either James Whitcomb Riley or of George Peck was Mark Twain's vision, in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), which combined elements of both these views. Twain mordantly depicted the depravity of both young and old in the slaveholding civilization on the riverbanks. But he also captured the freedom, or at least the dream of freedom, to be found in a life in nature, on the Mississippi. Much of the novels' beguiling power rests on their rapturous evocation of life beyond the constraints of the culture.\ \ \ Huckleberry came and went at his own free will. He slept on doorsteps in fine weather, and in empty hogsheads in wet; he did not have to go to school or to church, or call any being master, or obey anybody; he could go fishing or swimming when and where he chose, and stay as long as it suited him; nobody forbade him to fight; he could sit up as late as he pleased; he was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall; he never had to wash, nor put on clean clothes; he could swear wonderfully. In a word, everything that goes to make life precious, that boy had.\ \ \ Authority could be, must be, deceived and evaded. When the pressures of encroaching culture proved intolerable, Twain's young men survived by tricking people, Tom Sawyer's way, or by running away, Huck's. But no one could run away forever; it never crossed Hennery Peck's mind to try it. And Twain, sometimes reluctantly and always with difficulty, was realistic; whether in the territories of the West or on the mighty river, life was lived within society.\ All his life Tod Sloan combined Tom and Huck. In his early years he was Huck. Roaming the Indiana countryside with his dog Tony, he stayed away from school, took up smoking, became "crazy for firearms of all kinds," a passion he couldn't gratify until he was older because in those unenlightened days guns were not readily available to everyone. "I would go out in the fields with Tony and fish, fish, all day long." At other times he was Tom, tricking fellows older and bigger than he was, learning what he could get away with. "Sometimes I got near getting a licking, but I suppose I was too small for them to take very seriously, although I could sting them a bit with my tongue, which was bitter even then." (He always could talk, and one day he would dictate a book.) Later, there were stories that portray him as less a victim of size and circumstance, less innocent. It was said that by age nine he was already fond of man-sized cigars, that "his exploits and adventures knew no limit," that he preferred the company of grown men, that "nothing was too dangerous for him to attempt."\ The Blausers put an end to this freedom by threatening him with school. Todd sought refuge twenty miles away, "with my real mother's sister." His aunt let him stay with her for a day or two, but "she kept putting questions, asking me this, that and the other about my schooling and what I was going to do for a living." It was the Widow Douglas civilizing Huck. "She was a good church-woman and never could hold with my not being the same as all the other folk she knew." Tod wasn't the same, and never could be. So he trailed back to the Blausers' house only to find that he couldn't come home again. He had no home. Mrs. Blauser, "without letting me in the front door," asked "whether I had come for my trunk." Tod, who had no trunk and barely enough clothes to fill a small bag, got the point. "There was no question the situation spelt W-O-R-K." At age thirteen, Tod Sloan hit the road. He was on his own.\ \ \ After leaving Kokomo, Tod had to be Tom Sawyer, calculating the odds, cutting corners, scrambling to survive. James Whitcomb Riley didn't sing idylls about this Indiana. Gone was harmony with nature. Gone was childhood. (Adolescence hadn't been invented yet.) Soon to go was innocence. Their place was taken, abruptly, shockingly, by learning from the experience of ordinary daily life. Tod went to work in the nearby gas and oil fields, was injured in two explosions, treating his burns with linseed oil and lime water, which "seemed to shrivel me even smaller than I was before." He went back to Kokomo and did a "sort of general utility turn" in a livery stable but was fired because he was so puny. "Although I was willing enough they were always telling me about my helplessness." He looked up his real father, who was now living near Marion, Indiana, and had a new family, but his father did nothing for him. He was unwilling, or too poor, or both. Work turned up in a carriage factory for a while, then in a saloon—sweeping up, attending to the glasses, learning new swear words from the customers. "But it was the same old cry—`too small,'" so he had to beat it from there. "It was a bit of a knock-out for I used to put in a lot of elbow and wrist work for what my back couldn't do."\ Family (and nonfamily), local culture, class, poverty, all these institutions and social conditions were working on Tod Sloan in his wanderings. Nevertheless, the most important thing he had to learn to deal with in these years didn't come through experience or observation and was dictated by nature, not society: his size. Fully grown, he was under five feet in height. He weighed fifty or sixty pounds as he was growing up; in his twenties he weighed about ninety pounds. He wasn't a dwarf; he wasn't ill or disabled. But his small size was inescapable. There were some obvious roles for a very small man: he could work in a circus, become an entertainer, ride horses. In Tod's day there was the historical memory of Napoleon, diminutive but immensely powerful, and of Stephen A. Douglas, the "little giant," Abraham Lincoln's rival from nearby Illinois. Small consolation. What life made clear was that little people had always to look up, and had better look out, for themselves.\ In his meanderings Tod met "Professor" A. L. Talbot, a balloonist, a self-described aeronaut, who traveled about the countryside with various sideshows. He was a bit of a con man—the identification of the title professor with something bogus was a persistent aspect of nineteenth-century American culture. But Talbot saw more in Tod than anyone else ever had, so Tod joined up and went along with him. When balloon ascensions didn't draw, the two of them hustled to earn their keep by making toy balloons, which Tod sold. "I tell you I was some salesman, and often think I could have managed a department store if father had taken me by the back of the neck and forced me into business." Tod might indeed have made a good salesman. Words never failed him. Salesmen—"drummers" they were called—epitomized the aggressive, slyly knowing, corner-cutting, and dealmaking commercial culture of the time. An American journalist of the 1890s described these graduates of the Drummers' University, the school of hard knocks: "They know all stories, all jokes, all railroad routes, all hotels, all trades, all games. They are afraid of nothing. They take chances and jump at every opportunity."\ Tod Sloan learned his lessons about life from the harsh, shadowy culture of the fast-talking salesman, the carnival pitchman, and the racetrack tout, always on the make, always on the move, legal but essentially furtive. It was a culture of illusion, of sleight-of-hand, of trickery, of seeming more than being. It eluded neat categories of class. It was too occasional and improvised for the discipline of working-class industrial routine; it was entrepreneurial and wholly dependent on the market, but too disreputable, in its commonest forms, to be middle class. Those who were part of it were disdainful of the pieties of middle-class morality and in many ways hostile to the established order because their success depended on beating the system. But they resisted collaboration and were arch individualists, prizing anonymity.\ Get-rich-quick-and-easy, something-for-nothing, and taking-a-chance were the prevailing goals of the carnival, the racetrack, the dreams of the salesman. An American gambler believed that the average American was especially susceptible to the wiles of the con man and gambler because of his materialism and cupidity, his "insatiable greed for money, more money. The American eats with it, sleeps with it, dreams of it and lives with it. It is money, money all the time. Go to him with any proposition that has the least bit of plausibility and he will rush to it with the ardor of a boy coasting down hill on the snow." It was a culture essentially Calvinist. In a culture of original sinners, in which everyone was out to trick everyone, there was no sympathy for a victim, only contempt. Given its assumptions about human nature, there was a fitness in cheating the gullible. Joe Weil, a famous con man and swindler known as the Yellow Kid, insisted that "honest men do not exist." "I have never cheated any honest men," he said, "only rascals. They wanted something for nothing. I gave them nothing for something."\ Tod Sloan accepted this world. In his memoirs he admitted mistakes but didn't blame himself or others. But for all the matter-of-fact amorality of his narrative, there was in it, between the lines, a vulnerable yearning for a different way, for guidance. Tod Sloan was looking for someone older, wiser, bigger, who would take care of him, set him straight. Professor Talbot was the first of the men whom, in later years, he would identify with his needs. "We were quite a happy family with Talbot." The professor had done a lot of things. He had ridden as a jockey, performed as a clown in the circus, exhibited his equestrian skill by riding two horses, bareback, at the same time. The combative professor fought on the slightest provocation, scrapped for the love of it. Tod later concluded that he hadn't had a hot temper until he met Talbot, whose love of fighting sparked his own. Talbot brawled but never talked about his brawls. Anyone hustling for a living learned to keep his own counsel, to give nothing away. Talking was all right when it was just another way of disguising what was really going on. Talbot explained nothing—about himself, who he was, where he came from, where and how he grew up. A. L. Talbot had no history, only a past. In this he is like the innumerable others who left no records, dictated no books, belonged to nothing, cheated when they could, worked as they had to, and survived.\ Once, near Cullum, Indiana, they were heating up for an ascension. Talbot couldn't always get gas, and when he could it often cost too much. So he inflated his balloons in the original way, with hot air. Tod's job was to pile the pine logs and oil barrel staves that were burned to get enough hot vapor to fill the balloon for takeoff. On this occasion Tod saw flames burst out just as the other men on the ground were letting the balloon, and the professor, loose. "Don't go," Tod shouted, but it was too noisy for Talbot to hear him and "with the extra heat he went up all the quicker ... and I never thought I should see him alive again." At about fifteen hundred feet the balloon was fully on fire; it then collapsed, and the professor came down even quicker than he'd gone up, landing in a field. Somehow the scraps of the balloon's framework broke his fall; Talbot wasn't hurt, only knocked out. He was revived, taken round to a drugstore, and given a shot of brandy. "He got up about an hour after and went to a dance." The professor was tough.\ For the Boonesville, Indiana, fair, Talbot came up with a big new idea. He was paid an extra twenty-five dollars for promising a parachute act in connection with the conventional ascension. A boy would slip out of the balloon in a parachute. (Talbot had never seen a parachute, but he got a picture of one and copied it.) One morning he sprang his plan on Tod, who asked:\ \ \ "Who's the boy?"\ "You're the boy."\ "Oh, I am!"\ "You don't seem to like it, Tod."\ "It's all right. But what sort of thing is the parachute, the umbrella thing I am to come down in? Shall I be heavy enough to make it open out?"\ "Oh, you'll be all right," said the Professor, just as if he were saying "Pass the butter," but I began thinking it over and the more I looked up at the sky and began to think of having to slip down from the clouds the less I liked it.\ \ \ Tod began to think how he could get out of it. Sometime before this he had learned that his brother Cassius, "Cash," was in the neighborhood. So he told the professor that he wanted to leave. Talbot was sporting about it. "Perhaps you're right; go and join your brother." That was the last they saw of each other.\ \ \ Tod set out to look for Cash and eventually found him. "I saw a little fellow ahead of me, hiking a mile down a railroad track as hot as a furnace, carrying a pail of water in each hand. He had a long, peaked trotting driver's cap on, and looked the funniest guy I'd ever seen. I walked up behind him to see who he was, and I heard him whistling—and then, of course, I knew it was Cash. We embraced like brothers should. I was glad to see him and he me. We sat down by the track and talked things out."\ Cash was a jockey for a stable of horses near St. Louis, and he put Tod to work doing odd jobs. He learned how to rub down horses, to feed and care for them. Work around stables was often dirty, but it wasn't hard. The next step was to become an exercise boy, riding horses to warm them up, then to become a jockey, like Cash. The problem for stable boys who wanted to become jockeys was in getting a chance to ride and gain experience. There was no formal schooling, no apprenticeship; boys learned if they were quick-witted and observant, watching, watching what the others did. Tod's size made him a natural candidate as a featherweight jockey. But there was a special problem. Horses terrified Tod Sloan. He said that his fear of them was connected with a childhood incident; at a funeral he had climbed up on a horse that ran away, out of control. Death and horses got mixed up in his mind. He tried to shake off this fear when working with Cash, but every time he mounted a horse he got thrown, which only made things worse. He hated the whole thing. Still, he reminded himself that trying to ride horses was better than jumping from a balloon; he still had balloon nightmares, "dropping down from the sky with a parachute just out of clutching distance."\ Then Cash lost his job with the stable. The two brothers knocked around for a while, moving from place to place, ending up in Denver, where Tod tried riding again, only to be thrown once more. He kept trying because there wasn't anything else. When he was fourteen he and Cash went to Chicago, staying with their sister. Cash supported them by working as a carpenter and, on weekends, as a barber. "Of course little Tod couldn't be out of it," and he helped his brother by standing on a stool and putting in "some fine fancy work," lathering the faces of Cash's customers. In Kansas City he worked for a trainer named Jimmy Campbell, a kindly soul who insisted that Tod could become a success as a rider. Campbell took him east, to New Jersey, where he had his first glimpse of eastern racing. With Campbell's help he began to do what was necessary to overcome his fear—to understand horses. Tod's (or Campbell's) guiding insight was that horses "didn't want to be bullied." It was no good kicking and pulling at them. A rider had to find out each horse's peculiarities and then play up to them. This worked especially well with horses that had a reputation for being bad tempered and sulky. Tod's way with such a horse was Tom Sawyer's way with people; in the struggle between horse and rider for control it was necessary to fool the horse. "I would tug at his bridle a bit then I would relax. That made him think I had given it up—the struggle I mean—and he would strike out for all he was worth under the impression that he'd conquered me." Such a horse then did his best— "an his own account."\ So Tod started riding professionally. There are differing accounts about when this occurred. In one, "enamored of the turf and the sight of billowing silks," he haunted the barns and stables of a track in St. Louis and got his first mount in 1890. The editor of his memories, who ought to have known, wrote that Sloan "made the acquaintance of race horses in 1886," whatever that might mean. Sam Hildreth, later a notable trainer, encountered Tod in 1886, at the Latonia, Kentucky, racetrack; he was twelve and weighed sixty pounds. "He reminded you of a midget as he squatted on a horse's back." Hildreth gave him a mount, and though Tod's horse "finished nowhere," he handled himself well. Tod remembered his first race as in New Orleans, on Lovelace; he finished third, rode in four other races, and was out of the money in all of them. "If a man didn't want his horse to win, all he had to do was to send for Sloan." No doubt he exaggerated, consciously or not; it made his rise to fame more dramatic. But other people's accounts do suggest that he was not exaggerating when he wrote that "I hated myself for I didn't seem to improve at all." Tod was certainly not precocious. His vagrant rovings in these years—St. Louis, Chicago, New Orleans, a brief eastern visit—are the fitful gropings of someone trying to find his way. He insisted that he had decided to give up riding but was dissuaded by words that kept ringing mysteriously in his ears: "You may be able to ride some day."\ And then, in 1892 or 1893, he went to northern California for the winter racing, and that day came.

\ Jonathan YardleySloan's story is well worth telling and that John Dizikes tells it very well in Yankee Doodle Dandy....[H[is influence on his sport and on American culture was substantial and lasting. This first-rate book gives it, and him, all due credit.\ — Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ Tod Sloan (1874-1933) was the Yankee Doodle in George M. Cohan's musical--the phenomenon who became the winningest jockey in the U.S., then crossed the Atlantic to conquer the turf in England. He was, as Dizikes makes clear, the first sports mega-celebrity: "Where Tod Sloan led, Babe Ruth and Pel and Michael Jordan have followed." Alas for Sloan, after he had amassed fame and fortune, his popularity faded quickly, and he died, as he was born, in obscure poverty. In tracing the arc of Sloan's career, Dizikes (who won the National Book Critics' Circle award for Opera in America) paints a vivid canvas of the Gay '90s and what Dizikes calls its "flash culture," featuring Diamond Jim Brady, Lillian Russell and "plungers" (big gamblers) like Pittsburgh Phil Smith. Part of Sloan's success--and notoriety-- as a jockey was his origination of the "forward seat," with the jockey sitting up on the horse's withers and crouched forward over its neck, the position now standard for all jockeys but still crude and controversial in the 1890s. But did Sloan originate it, Dizikes asks, or only popularize it? Part of the fascinating social history that Dizikes reconstructs surrounding horse racing in that era concerns the lower-class origins of the forward seat. He also portrays the shady world of the sport of kings in the U.S. at the time, when cheating was rampant--races were commonly fixed, and horses were doped (one actually dropped dead in the winner's circle); it was a suspicion of cheating that led to Sloan's downfall. Dizikes's well-written and engaging history deserves a wide readership and Yale is planning a national media campaign (based on Dizikes's NBCC-winning reputation), with special outreach to sports media, so word will get out widely to fans of horse racing, sports enthusiasts in general, and especially readers interested in the role of sports within the wider culture. 30 illus. (Oct.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ Library JournalYankee Doodle was a horse ridden by the world's greatest jockey in a George M. Cohan play. Tod Sloan was perhaps the greatest American jockey, with a high winning percentage of mounts in the United States and England. He was also commemorated in Hemingway's short story, "My Old Man." The key to his success was an innovative style of riding that is now the norm in horse racing. Sportswriters of the time labeled his style the "Monkey Seat": Sloan rode motionless, seated high up and lying forward on the horse's neck, as all jockeys do today. This work is fun to read for Sloan's engaging world of hedonistic characters--lawyers, land barons, pugilists, Wall Streeters, captains of industry, even English royalty--all gambling, spending, eating, and constantly drinking. Sloan's story is of a physically small person becoming a giant among his peers. Although he made a fortune, the hard-living gambler did not hold on to much of it. Optimistic to the end, he ordered cigars on his deathbed in 1933. A charming, well-researched life and times of a little revolutionary; highly recommended. Marty Soven, Woodside, NY Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\\ \ \ \ \ Wall Street JournalThe Tod Sloan story has finally received the comprehensive treatment and analysis it deserves. . . . a beautifully crafted work--Ray Kerrison, Wall Street Journal\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA thoroughbred biography of the brash American jockey whose unconventional style of riding "overturned two hundred years of tradition."\ \ \ \ \ Wall Street Journal“A beautifully crafted work, even-handed in its evaluation of a controversial figure, artfully set against the colorful Gay Nineties and richly spiced with tidbits of racing lore.”—Wall Street Journal\ \ \ \ \ Thoroughbred Times“Historical investigative reporting at its finest, . . . A story of gambling, sport, and scandal from the Wild West to Victorian England.”—Thoroughbred Times\ \ \ \ \ New York Times Book Review“You will not forget Tod Sloan.”—New York Times Book Review\ \