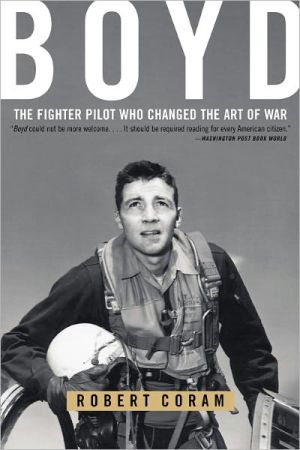

Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War

"John Boyd may be the most remarkable unsung hero in all of American military history. Some remember him as the greatest U.S. fighter pilot ever - the man who, in simulated air-to-air combat, defeated every challenger in less than forty seconds. Some recall him as the father of our country's most legendary fighter aircraft - the F-15 and F-16. Still others think of Boyd as the most influential military theorist since Sun Tzu. They know only half the story." Boyd, more than any other person,...

Search in google:

John Boyd was the greatest fighter pilot in American history. From the proving ground of the Korean War, he went on to win renown as the instructor who defeated every pilot who challenged him in less than 40 seconds. But what made Boyd a man for the ages was what happened after he left the cockpit. Charles Krulak ...an extremely accurate picture of a man whose contributions to the art of war rival those of the greatest military minds...

Boyd\ The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War \ \ By Robert Coram \ Back Bay Books\ Copyright © 2004 Robert Coram\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0316796883 \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ Haunted Beginnings \ ERIE, Pennsylvania, is a hard town, a blue-collar town, a grubby and decrepit town that has more in common with its fellow Great Lakes rust-belt towns of Buffalo and Cleveland than it has with Pennsylvania cities. Perched high in the northwestern corner of Pennsylvania, with its face toward the lake and its back toward the rest of the state, Erie is the only lake port town in Pennsylvania. Even people in other parts of the state often are surprised to learn that until the last year or so it was their third largest municipality, after the elegant and history-wrapped city of Philadelphia and the brawny sophistication of Pittsburgh. The town of about one hundred thousand just doesn't seem that big-not so much because it is remote, which it is, but because it is so narrow, so provincial.\ The one natural feature in Erie worthy of note is the glorious Presque Isle Peninsula, which juts seven miles into the lake and forms a bay that in the summer is ideal for boating and in the winter for ice sailing. "The Peninsula," as it is called, offers not only eleven beaches but an untrammeled spot of wilderness, a glorious combination of wetlands and walking trails that draws people by the thousands. It is a unique natural bounty.\ But Erie also is suited for being an industrial port, an opening onto the Great Lakes. And almost from its beginning the town has been caught between the polarities of wanting to be a tourist destination and wanting to be an industrial port. The desire to be an industrial city has prevailed to the degree that contamination from local industries may never be removed from the muck at the bottom of the lake. Erie long has searched for that which made it unique-for events or people in its history worth boasting about to the outside world. Such events and such people have been few and, when viewed from other parts of America, may seem curious. For example, it is a matter of considerable local pride that in the Battle of Lake Erie, an engagement during the War of 1812, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry sailed aboard a ship built in Erie. Then there was Erie's Colonel Strong Vincent, who stood in the midst of battle at Gettysburg and exhorted his troops with a riding crop-an act that resulted in his being killed by a Confederate sniper. While most historians agree that Colonel Joshua Chamberlain was the Union hero at Gettysburg, people in Erie say Strong Vincent saved the day. And there was the train that carried the body of President Abraham Lincoln from Washington back home to Illinois, a train that passed through Erie.\ In the 1920s, Hubert and Elsie Boyd, along with three children- two boys and a girl-lived in a brown, two-story, frame house at 514 Lincoln Avenue on the west side of Erie, only a block from the bay. This was one of the most prestigious parts of Erie, and Lincoln Avenue itself was the sort of street parents longed for: a street of well maintained homes, a safe street, a street famous for its umbrageous maples and spreading oaks. The homes, most with front porches, breasted against the sidewalk in a neat row. The street ended a long block away at a steep bluff overlooking the bay. Beyond the bay was the Peninsula and beyond the Peninsula was Lake Erie and beyond Lake Erie was the vast horizon and Canada.\ Hubert Boyd paid $16,500 for the house. Inside, Elsie had an eye for the fine details. She installed dark hardwood floors in the dining room-not just any hardwood, but narrow tight-fitting boards of dark oak, the best that money could buy. She bought a fine mahogany dining-room table and placed a runner of Irish linen atop it. For the living room, where her growing family would spend long winter evenings, she bought a cast-iron gas heater, and to brighten those winter evenings she covered the walls with pink paper. The living room's other feature was a black Steinway, a gift from Hubert. Elsie liked to play it, having taught piano before she was married.\ For Erie in the late 1920s it was a comfortable middle-class home. Hubert Boyd was a traveling salesman for HammerMill Paper Company, and a job at "the HammerMill" was both prestigious and wellpaying. Elsie Boyd was the daughter of Julia and Rudolph Beyer. Her father farmed a small piece of land just south of Erie. Elsie was a German Presbyterian, an ample woman with enormous pride and the self-confidence to freely express her beliefs, many of which were synthesized in pithy expressions such as "The world is not the way you want it to be. The world is the way it is." Or "You have to speak up in this world." Or "Never give up and never give in." Her voice was deep and authoritative, and when she spoke there rarely was any doubt about her meaning.\ For his part, Hubert Boyd was the son of Mary Golden and Thomas Boyd. Thomas worked on a boat, probably a fishing boat, that plied the Great Lakes, and his son was a tall, thin, happy-go-lucky fellow with brown eyes and a shock of wavy black hair. Although he was Catholic and had baptized his children as Catholics, he preferred the golf course to church.\ It was into this contented and fortunate family that John Richard Boyd was born on January 23, 1927.\ When Boyd was born, his mother and father shared the front bedroom. His sister Marion, age eleven, had her own room. The third bedroom was shared by the boys. Bill, who had just turned ten, and Hubert-called Gerry-who was four. John's crib stayed in the bedroom with his parents. On September 23, 1928, Ann was born- the fifth and last child in the Boyd family.\ After Ann's birth, the prospect of feeding and clothing five children began to loom large in the mind of Hubert Boyd. He had never gone to college. His quick smile and Irish ebullience had given him a good job at the HammerMill, but he knew that his natural gifts could take him only so far. He wanted his children to have advantages he never had. He preached to Marion the need for a college education. During the fall of 1926 he talked to a neighbor about buying an insurance policy that would pay for his children's education should anything happen to him. But he was young and decided to wait.\ In late November of 1929, Hubert spent several weeks "down south" on a sales trip. No one remembers exactly where, only, as Marion says, that it was "somewhere down there where it was warm." He came home to record cold and record snowfall, celebrated Christmas with his family, and in mid-January contracted lobar pneumonia. The family attributed the pneumonia to the drastic difference in temperature between the South and Erie, with the clear implication that the South was to blame. Doctors, however, generally attribute lobar pneumonia either to chronic smoking or to a systemic infection, and Hubert was a heavy smoker.\ During Hubert's illness all the children save Ann were farmed out to their father's sisters in south Erie; Mrs. Boyd would take care of her husband and she would do it on her own. The children rarely visited. Marion came home once and found her father had been moved from his cold bedroom into her room. The windows were open to allow the wind off the lake to blow through-the idea, current in the medical community of the time, was to "freeze out" the pneumonia. Marion sat in a chair at the top of the steps, shivered with the cold, and cried.\ Icy temperatures and bitter winds were insufficient to cure the pneumonia and Hubert Boyd died January 19, 1930. He was thirtyseven, and was buried on John's third birthday.\ When Marion was in her mideighties, she said her father's death was not as painful as it might appear. In most families the father is home every night. But her father was "gone all the time." She said that for months after the funeral she thought, "Oh, Dad's on a trip." But she was a teenager when her father died and her recollection was softened by the passage of seventy years. John was too young to understand the concept of travel and returning home. Even if he could, there had to have been a moment when the painful realization sank in that he would grow up without a father, that he was therefore different from other children.\ Hubert Boyd had only $10,000 in life insurance and most of that was used to pay off the mortgage. Elsie faced the insurmountable task of supporting and rearing five children. Ann and John were little more than infants, so whatever work she found would have to enable her to stay at home. But the Great Depression was spreading across America and even a bustling port city such as Erie was beginning to feel the effects.\ She had still another burden, a self-imposed burden. As the wife of a salesman for the HammerMill, Elsie had enjoyed a certain lifestyle and a certain community standing. She wanted to maintain both. This meant people in Erie must think she did not really need to work. She began baking cakes and selling them to neighbors. None of the children remembers the price, but in the early 30s she could have made only a few cents on each cake. She made various sorts but became famous around Erie for her devil's food cake and, at Christmas, her date-and-nut cake. One Christmas she had orders for eighty cakes, and for several weeks the house turned into a bakery. For so many cakes to come from such a small oven in such a short period of time necessitated split-second timing from dawn to dusk. Elsie Boyd did not allow the children to help. They were ordered to stay out of the kitchen.\ Mrs. Boyd also began selling Christmas cards and stationery, and found a third job conducting telephone solicitations for advertisements that went inside program booklets for banquets. She did this from the house on Lincoln Avenue and tended to the children between calls. Marion remembers that when her mother solicited ads from the home telephone, her voice was deep and commanding, "strong, persuasive, and in control." Mrs. Boyd wanted people in Erie to know that even though her husband was dead, nothing had changed. The Boyd family of Lincoln Avenue was doing quite well, thank you. But events were gathering, momentous events, beyond even the ability of the redoubtable Elsie Boyd to control.\ Elsie settled into a curious dichotomy in raising her children. On the one hand she allowed them almost free reign, especially around the house. The postman once reported to Mrs. Boyd that John was running naked through the backyard and playing in the sprinkler. At the dinner table, tempers often exploded and the children shouted at each other. Much about the household was loud and raucous, freewheeling and unrestrained.\ If Mrs. Boyd granted her children unusual freedoms within her house, she was more than diligent in imparting rules for outside the house. She inculcated her children with a protective mechanism they remembered all their lives. Over and over again she said if people knew too much about the Boyd family they would use the knowledge in a critical manner. Never tell people what you don't want repeated, she preached. People will seek out your weaknesses and faults, so tell them only of your strong points. No family matters must ever be mentioned beyond the front door. This resulted in the Boyd children being extraordinarily reticent about all but the most inconsequential of family matters, even when they reached old age.\ While Elsie had striven mightily to have people in Erie think she was as comfortable as before her husband died, inside the home she turned poverty into a cardinal virtue. She taught all her children, but especially John since he was at his most malleable age, that they had principles and integrity often lacking in those with money and social position. She hammered into John that as long as he held on to his sense of what was right, and as long as his integrity was inviolate, he was superior to those who had only rank or money. She also taught him that a man of principle frightened other people and that he would be attacked for his beliefs, but he must always keep the faith. "If you're right, you're right," she said.\ For several years after her husband died, Elsie maintained a semblance of religion in her household. Because her husband had been a Catholic and because all the children were baptized in the Catholic Church, she encouraged Marion and Gerry to attend church. But she was becoming increasingly annoyed by what she saw as church pressure for greater financial contributions.\ Then came the day when Marion, who was studying for her Con- firmation, could not remember her catechism. Marion reported to her mother that the priest ridiculed her in front of the class and made her kneel before him "like he was a tin god." Such authoritarian behavior on the part of priests then was the rule rather than the exception, but Elsie Boyd-a Presbyterian and a mother burdened with protecting her children against the world-was furious at the way the priest had humiliated Marion and, by extension, her family. She called the priest and said, "I have enough trouble trying to keep this family together without having a priest pick on my children." When the priest protested, Mrs. Boyd laced into him with even more animus. The priest insisted he was right, at which point Mrs. Boyd ended the conversation by serving notice she was removing her children from the Catholic Church.\ John was too young to be troubled by this. But Marion had heard what happened to children who left the church and she thought, "Oh, my. I'm going to hell." Two of Hubert Boyd's sisters, both of whom were devout Catholics, were more than a little disturbed by this theological shift and feared for the souls of the children. Bitter recriminations ensued.\ Elsie, as usual, was unbending. These were her children and she would raise them as she saw best. Her dead husband's sisters had no voice in the matter. She summarily tossed them from her house; it would be years before any of the Boyd children were allowed to visit the two aunts.\ This was not the last time Elsie was to demonstrate her willingness to sever a relationship with any person or any institution that offended her. She could do it without a second thought, without looking back, without any willingness to discuss the issue. Once she shut the door it was closed forever. John learned by her example, and it was a lesson he would remember.\ A few weeks later Elsie withdrew her children from the Catholic Church and decided that John would be raised as a Presbyterian. So one Sunday Marion drove John to the Church of the Covenant in downtown Erie and enrolled him in Sunday School. But it was not long before Elsie decided the Presbyterians were little better than the Catholics. "All they want is money," she complained. She had no money for the church. She severed her relationship with the Presbyterians and withdrew John from Sunday School. For years she inveighed against organized religion.\ \ Continues...\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from Boyd by Robert Coram Copyright © 2004 by Robert Coram.\ Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ Charles Krulak...an extremely accurate picture of a man whose contributions to the art of war rival those of the greatest military minds...\ \ \ \ \ James SchlesingerThe military services should welcome more people like Colonel John Boyd.\ \ \ Los Angeles TimesWhether or not Secretary Rumsfeld has truly absorbed Sun Tzu's subtle maxims may be open to question, but Robert Coram's engrossing biography, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, should definitely be on the bedside tables of all our current military leadership. Boyd was an Air Force fighter pilot who was never promoted beyond colonel, who wrote next to nothing, imparting his ideas by means of oral briefings, but who is nevertheless considered by many to be the greatest strategic thinker this country has ever produced, "the American Sun Tzu." — Andrew Cockburn\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyJohn Boyd (1927-1997) was a brilliant and blazingly eccentric person. He was a crackerjack jet fighter pilot, a visionary scholar and an innovative military strategist. Among other things, Boyd wrote the first manual on jet aerial combat, was primarily responsible for designing the F-15 and the F-16 jet fighters, was a leading voice in the post-Vietnam War military reform movement and shaped the smashingly successful U.S. military strategy in the Persian Gulf War. His writings and theories on military strategy remain influential today, particularly his concept of the "OODA (Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action) Loop," which all the military services-and many business strategists-use to this day. Boyd also was a brash, combative, iconoclastic man, not above insulting his superiors at the Pentagon (both military and civilian); he made enemies (and fiercely loyal acolytes) everywhere he went. His strange, mercurial personality did not mesh with a military career, making his 24 years in the Air Force (1951-1975) difficult professionally and causing serious emotional problems for Boyd's wife and children. Coram's worthy biography is deeply researched and detailed, down to describing the fine technical points of some of Boyd's theories. A Boyd advocate (he "contributed as much to fighter aviation as any man in the history of the Air Force," Coram notes), Coram does not shy away from Boyd's often self-defeating abrasiveness and the neglect and mistreatment of his long-suffering wife and children, and keeps the story of a unique life moving smoothly and engagingly. (Oct. 30) Forecast: Last year's The Mind of War: John Boyd and American Security (Smithsonian) was based on interviews with Boyd, but was more concerned with his ideas and their development than with a full telling of the life. Look for more interest in Boyd should his techniques be on display on CNN. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsProfanity-laden, action-filled biography of legendary Air Force pilot, instructor, and aircraft design theorist John Richard "Forty-Second" Boyd. Veteran journalist, novelist, and nonfiction author Coram (Caribbean Time Bomb, 1993, etc.) portrays Boyd as a visionary whose no-quarter-taken pursuit of weapons improvement so infuriated the bureaucrats that he was denied a generalship despite being recognized as a near genius. After two years as an Air Force mechanic, Boyd made his mark as a pilot in Korea and became a legend teaching others to fly, using his unique acrobatics to get on the tail and "hose" a mock enemy fighter in less than 40 seconds, a feat that taxed both pilot and aircraft. The highly inquisitive Boyd persuaded the Air Force to finance his engineering studies at Georgia Tech, where he learned thermodynamics and formulated his revolutionary theory on design factors that would quicken a fighter pilot's ability to get the better of an enemy. Real information (potential and kinetic energy from engine thrust, aircraft lift and drag, g-forces endurable, etc.) replaced conventional reliance on the often-inflated aircraft speed and range claims of bureaucrats who believed that the more complex a weapon, the more gizmos it carried, and the greater its cost, the better. Higher costs meant added layers of command and accelerated promotions for the spear-carriers, who cared far less about actual performance vis-à-vis that of prospective enemies' weapons. But Boyd's graphs of the swept-wing F-111 fighter and the acclaimed B-1 bomber showed that neither could withstand an onslaught from an ordinary MIG fighter. Soon his theories swept the government, the defense industry, and Congress;the crafts he designated "lemons" never saw combat. Nonetheless, Boyd died in poverty as a retired colonel, best remembered by a handful of supporters he called "Acolytes." Required reading for frustrated innovators, aviation buffs, and Horatio Algers intent on improving the world against the best efforts of ever-prevailing deal-busters and naysayers.\ \