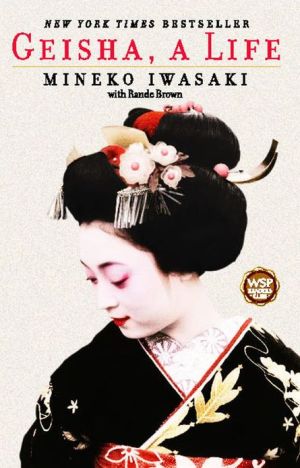

Geisha, a Life

No woman in the three-hundred-year history of the karyukai has ever come forward in public to tell her story — until now.\ "Many say I was the best geisha of my generation," writes Mineko Iwasaki. "And yet, it was a life that I found too constricting to continue. And one that I ultimately had to leave." Trained to become a geisha from the age of five, Iwasaki would live among the other "women of art" in Kyoto's Gion Kobu district and practice the ancient customs of Japanese entertainment. She...

Search in google:

Celebrated as the most successful geisha of her generation, Mineko Iwasaki was only five years old when she left her parents' home for the world of the geisha. Publishers Weekly From age five, Iwasaki trained to be a geisha (or, as it was called in her Kyoto district, a geiko), learning the intricacies of a world that is nearly gone. As the first geisha to truly lift the veil of secrecy about the women who do such work (at least according to the publisher), Iwasaki writes of leaving home so young, undergoing rigorous training in dance and other arts and rising to stardom in her profession. She also carefully describes the origins of Kyoto's Gion Kobu district and the geiko system's political and social nuances in the 1960s and '70s. Although it's an autobiography, Iwasaki's account will undoubtedly be compared to the stunning fictional description of the same life in Arthur Golden's Memoirs of a Geisha. Lovers of Golden's work-and there are many-will undoubtedly pick this book up, hoping to get the true story of nights spent in kimono. Unfortunately, Iwasaki's work suffers from the comparison. Her writing style, refreshingly straightforward at the beginning, is far too dispassionate to sustain the entire story. Her lack of reflection and tendency toward mechanical description make the work more of a manual than a memoir. In describing the need to be nice to people whom she found repulsive, she writes, "Sublimating one's personal likes and dislikes under a veneer of gentility is one of the fundamental challenges of the profession." Iwasaki shrouds her prose in this mask of objectivity, and the result makes the reader feel like a teahouse patron: looking at a beautiful, elegant woman who speaks fluidly and well, but with never a vulnerable moment. (Oct. 1) Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.

Introduction\ In the country of Japan, an island nation in East Asia, there are special districts, known as karyukai, that are dedicated to the enjoyment of aesthetic pleasure. These are the communities where the professionally trained female artists known as geisha live and work.\ Karyukai means "the flower and willow world." Each geisha is like a flower, beautiful in her own way, and like a willow tree, gracious, flexible, and strong.\ No woman in the three hundred-year history of the karyukai has ever come forward in public to tell her story. We have been constrained by unwritten rules not to do so, by the robes of tradition, and by the sanctity of our exclusive calling.\ But I feel it is time to speak out. I want you to know what it is really like to live the life of a geisha, a life filled with extraordinary professional demands and richly glorious rewards. Many say I was the best geisha of my generation; I was certainly the most successful. And yet, it was a life that I found too constricting to continue. And one that I ultimately had to leave.\ It is a story that I have long wanted to tell.\ My name is Mineko.\ This is not the name my father gave me when I was born. It is my professional name. I got it when I was five years old. It was given to me by the head of the family of women who raised me in the geisha tradition. The surname of the family is Iwasaki. I was legally adopted as the heir to the name and successor to ownership of the business and its holdings when I was ten years old.\ I started my career very early. Events that happened when I was only three years old convinced me that it was what I was meant to do.\ I moved into the Iwasaki geisha house when I was five and began my artistic training when I was six. I adored the dance. It became my passion and object of greatest devotion. I was determined to become the best and I did.\ The dance is what kept me going when the other requirements of the profession felt too heavy to bear. Literally. I weigh 90 pounds. A full kimono with hair ornaments can easily weigh 40 pounds. It was a lot to carry. I would have been happy just to dance, but the exigencies of the system forced me to debut as an adolescent geisha, a maiko, when I was fifteen.\ The Iwasaki geisha house was located in the Gion Kobu district of Kyoto, the most famous and traditional karyukai of them all. This is the community in which I spent the entirety of my professional career.\ In Gion Kobu we don't refer to ourselves as geisha (meaning "artist") but use the more specific term geiko, "woman of art." One type of geiko, famed throughout the world as the symbol of Kyoto, is the young dancer known as a maiko, or "woman of dance." Accordingly, I will use the terms geiko and maiko throughout the rest of this book.\ When I was twenty I "turned my collar," the rite of passage that signals the transformation from maiko to adult geiko. As I matured in the profession, I became increasingly disillusioned with the intransigence of the archaic system and tried to initiate reforms that would increase the educational opportunities, financial independence, and professional rights of the women who worked there. I was so discouraged by my inability to effect change that I finally decided to abdicate my position and retire, which, to the horror of the establishment, I did at the height of my success, when I was twenty-nine years old. I closed down the Iwasaki geisha house, then under my control, packed up the priceless kimono and jeweled ornaments contained within, and left Gion Kobu. I married and am now raising a family.\ I lived in the karyukai during the 1960s and 1970s, a time when Japan was undergoing the radical transformation from a post-feudal to a modern society. But I existed in a world apart, a special realm whose mission and identity depended on preserving the time-honored traditions of the past. And I was a fully committed to doing so.\ Maiko and geiko start off their careers living and training in an establishment called an okiya (lodging house), usually translated as geisha house. They follow an extremely rigorous regimen of constant classes and rehearsal, similar in intensity to that of a prima ballerina, concert pianist, or opera singer in the West. The proprietress of the okiya supports the geiko fully in her efforts to become a professional and then helps manage her career once she makes her debut. The young geiko lives in the okiya for a contracted period of time, usually five to seven years, during which time she repays the okiya for its investment. She then becomes independent and moves out on her own, though she continues to maintain an agency relationship with her sponsoring okiya.\ The exception to this is a geiko who has been designated as an atotori, an heir to the house, its successor. She carries the last name of the okiya, either through birth or adoption, and lives in the okiya throughout her career.\ Maiko and geiko perform at very exclusive banquet facilities known as ochaya, often translated literally as "teahouses." Here we entertain regularly at private parties for select groups of invited patrons. We also appear publicly in a series of annual performance events. The most famous of these is the Miyako Odori ("cherry dances"). The dance programs are quite spectacular and draw enthusiastic audiences from all over the world. The Miyako Odori takes place for the month of April in our own theater, the Kaburenjo.\ There is much mystery and misunderstanding about what it means to be a geisha or, in my case, a geiko. I hope my story will help explain what it is really like and also serve as a record of this unique component of Japan's cultural history.\ Please, journey with me now into the extraordinary world of Gion Kobu.\ Copyright © 2002 by Mineko Iwasaki

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ The geisha has long been a mystery to those in the West. In her compelling memoir, Mineko, often called the best geisha of her generation, reveals the secretive world that inspired a bestselling fictional counterpart, Arthur Golden's bestselling Memoirs of a Geisha. \ Mineko's remarkable story dispels Western myths about the geisha as prostitute and describes a demanding life as a highly trained artist. With an even and objective voice, she tells of leaving home at the age of four to enter a geisha house. Here, Mineko made her fame and fortune as a dancer. Appearing and entertaining at as many as ten parties an evening, she would dance for ten minutes at each and earn tens of thousands of dollars for the night's work. Mineko also covers the importance of appearance, describing the elements of beauty, including the kimono. These garments were a special -- and costly -- part of a geisha's appearance, and could only be worn a few times.\ In Geisha, Mineko Iwasaki leads us through a fascinating profession. While a glossary of Japanese terms would have been helpful, nothing detracts from this powerful and intimate glimpse into a mysterious world.\ This is a fantastic book that will enthrall its readers. Glenn Speer\ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyFrom age five, Iwasaki trained to be a geisha (or, as it was called in her Kyoto district, a geiko), learning the intricacies of a world that is nearly gone. As the first geisha to truly lift the veil of secrecy about the women who do such work (at least according to the publisher), Iwasaki writes of leaving home so young, undergoing rigorous training in dance and other arts and rising to stardom in her profession. She also carefully describes the origins of Kyoto's Gion Kobu district and the geiko system's political and social nuances in the 1960s and '70s. Although it's an autobiography, Iwasaki's account will undoubtedly be compared to the stunning fictional description of the same life in Arthur Golden's Memoirs of a Geisha. Lovers of Golden's work-and there are many-will undoubtedly pick this book up, hoping to get the true story of nights spent in kimono. Unfortunately, Iwasaki's work suffers from the comparison. Her writing style, refreshingly straightforward at the beginning, is far too dispassionate to sustain the entire story. Her lack of reflection and tendency toward mechanical description make the work more of a manual than a memoir. In describing the need to be nice to people whom she found repulsive, she writes, "Sublimating one's personal likes and dislikes under a veneer of gentility is one of the fundamental challenges of the profession." Iwasaki shrouds her prose in this mask of objectivity, and the result makes the reader feel like a teahouse patron: looking at a beautiful, elegant woman who speaks fluidly and well, but with never a vulnerable moment. (Oct. 1) Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ KLIATTNow in her fifties, Mineko Iwasaki was once the best geisha of her generation, retiring at 29 because of disillusionment with the archaic system of her profession. Her intimate autobiography takes readers into the secret world of the karyukai, where geisha are trained in the arts. She dispels the myth that geisha are prostitutes. In fact, they are professional entertainers who perform at exclusive banquet facilities known as ochaya. Iwasaki left her home when she was five to live in the karyukai and seldom saw her parents. She was surprised to find two elder sisters working there, sisters she had known nothing about. Initially she lived a pampered life. She excelled at the dance, but also played musical instruments. After she made her debut, she was much in demand, but her popularity did not come without a cost. She writes, "It's hard to imagine living in a world where everyone—your friends, your sisters, even your mother—is your rival. Inevitably, all of this took a psychological toll...I suffered periodic anxiety, insomnia, and difficulty speaking." She used comedy to ease the stress. She met a famous actor, fell in love, and became his lover even though he was married. He promised to divorce but never did. Finally, she met an artist. They married 23 days later and now have a daughter. Behind the smiling faces and perfect grooming of geishas is a life of pain, stress, disappointment, limited opportunities, a narrow education, and hard work. Iwaski's book is a vivid picture of a hidden part of Japanese culture. Sixteen pages of photos accompany the text. KLIATT Codes: SA—Recommended for senior high school students, advanced students, and adults. 2002,Simon & Schuster, Washington Square Press, 297p. illus., Ages 15 to adult. \ —Janet Julian\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIwasaki, who started training for her demanding profession at age four, here takes readers into the rarely glimpsed world of the geisha. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAn exponent of the highly ritualized—and highly misunderstood—Japanese art form tells all. Or at least some. \ In her homeland, Iwasaki’s account begins, ". . . there are special districts, known as karyukai, that are dedicated to the enjoyment of aesthetic pleasure." This "flower and willow world" has been a very specialized field for Japanese women for the last 300 years, she adds, and it endures even today. During the 1960s and early ’70s, "when Japan was undergoing the radical transformation from a post-feudal to a modern society," the now-52-year-old Iwasaki trained to become "certainly the most successful" geisha of her generation; had she not taken up this line of work, she writes, she would instead have become a Buddhist nun or a policewoman. Attaining the top spot, as in any other show-business venue, meant waging crafty campaigns against jealous rivals; training endlessly in the arts of singing, dancing, conversation, and walking in a mincing gait; putting in 20-hour days; and cultivating the friendship of the otokosh (dressers), who assure that all is well in the kimono and obi department while acting as "the standard brokers of various relationships within the karyukai." This account, the first of its kind from a contemporary Japanese woman, does a good job of spelling out the "aesthetic pleasure" component of the geisha’s world, although the author is quite reticent about other kinds of pleasure that the geisha is alleged to provide; on this point, Liza Dalby’s Geisha (1983), set at about the same time as Iwasaki’s memoir and offering another firsthand view, is more forthcoming. Iwasaki’s narrative can sometimes be a little dense; as a not untypical passage puts it, "Idecided to try to orchestrate the company myself by asking the okasan of the ochaya to invite certain geiko to attend the ozashiki for which I was booked"—quite a mouthful for the uninitiated.\ Still, a valuable look at a little-known world, and an intimate glimpse into Japanese culture.\ \ \