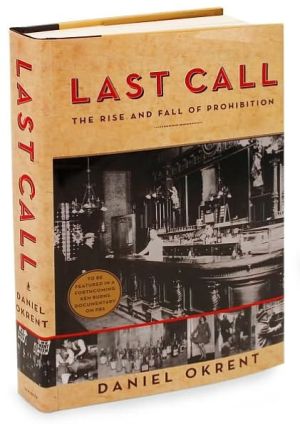

Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition

A brilliant, authoritative, and fascinating history of America’s most puzzling era, the years 1920 to 1933, when the U.S. Constitution was amended to restrict one of America’s favorite pastimes: drinking alcoholic beverages.\ From its start, America has been awash in drink. The sailing vessel that brought John Winthrop to the shores of the New World in 1630 carried more beer than water. By the 1820s, liquor flowed so plentifully it was cheaper than tea. That Americans would ever agree to...

Search in google:

A brilliant, authoritative, and fascinating history of America’s most puzzling era, the years 1920 to 1933, when the U.S. Constitution was amended to restrict one of America’s favorite pastimes: drinking alcoholic beverages. From its start, America has been awash in drink. The sailing vessel that brought John Winthrop to the shores of the New World in 1630 carried more beer than water. By the 1820s, liquor flowed so plentifully it was cheaper than tea. That Americans would ever agree to relinquish their booze was as improbable as it was astonishing. Yet we did, and Last Call is Daniel Okrent’s dazzling explanation of why we did it, what life under Prohibition was like, and how such an unprecedented degree of government interference in the private lives of Americans changed the country forever. Writing with both wit and historical acuity, Okrent reveals how Prohibition marked a confluence of diverse forces: the growing political power of the women’s suffrage movement, which allied itself with the antiliquor campaign; the fear of small-town, native-stock Protestants that they were losing control of their country to the immigrants of the large cities; the anti-German sentiment stoked by World War I; and a variety of other unlikely factors, ranging from the rise of the automobile to the advent of the income tax. Through it all, Americans kept drinking, going to remarkably creative lengths to smuggle, sell, conceal, and convivially (and sometimes fatally) imbibe their favorite intoxicants. Last Call is peopled with vivid characters of an astonishing variety: Susan B. Anthony and Billy Sunday, William Jennings Bryan and bootlegger Sam Bronfman, Pierre S. du Pont and H. L. Mencken, Meyer Lansky and the incredible—if long-forgotten—federal official Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who throughout the twenties was the most powerful woman in the country. (Perhaps most surprising of all is Okrent’s account of Joseph P. Kennedy’s legendary, and long-misunderstood, role in the liquor business.) It’s a book rich with stories from nearly all parts of the country. Okrent’s narrative runs through smoky Manhattan speakeasies, where relations between the sexes were changed forever; California vineyards busily producing “sacramental” wine; New England fishing communities that gave up fishing for the more lucrative rum-running business; and in Washington, the halls of Congress itself, where politicians who had voted for Prohibition drank openly and without apology. Last Call is capacious, meticulous, and thrillingly told. It stands as the most complete history of Prohibition ever written and confirms Daniel Okrent’s rank as a major American writer. The Barnes & Noble Review Okrent's meticulous research brings new dimension to the enduring cultural images of the era. Sure, there were the storied speakeasies like New York's 21 Club, which benefited from Prohibition's underfunded, understaffed, and frequently apathetic enforcement. But there were also bootlegging rabbis who took advantage of an exemption for sacramental drink by organizing fake congregations through which they distributed wine and enriched themselves. The author shows how bootlegging, which began as largely local and nonviolent activity, was taken over by organized criminal enterprises, and he marvels at the "romantic glow" that has come to surround murderous gangsters like Al Capone.

Last Call\ \ By Daniel Okrent \ Scribner\ Copyright © 2010 Daniel Okrent\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-7432-7702-0 \ \ \ Prologue\ January 16, 1920 \ THE STREETS OF San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons, and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings, and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered on the last possible day before transporting their contents would become illegal. The next morning, the Chronicle reported that people whose beer, liquor, and wine had not arrived by midnight were left to stand in their doorways "with haggard faces and glittering eyes." Just two weeks earlier, on the last New Year's Eve before Prohibition, frantic celebrations had convulsed the city's hotels and private clubs, its neighborhood taverns and wharfside saloons. It was a spasm of desperate joy fueled, said the Chronicle, by great quantities of "bottled sunshine" liberated from "cellars, club lockers, bank vaults, safety deposit boxes and other hiding places." Now, on January 16, the sunshine was surrendering to darkness.\ San Franciscans could hardly have been surprised. Like the rest of the nation, they'd had a year's warning that the moment the calendar flipped to January 17, Americans would only be able to own whatever alcoholic beverages had been in their homes the day before. In fact, Americans had had several decades' warning, decades during which a popular movement like none the nation had ever seen-a mighty alliance of moralists and progressives, suffragists and xenophobes-had legally seized the Constitution, bending it to a new purpose.\ Up in the Napa Valley to the north of San Francisco, where grape growers had been ripping out their vines and planting fruit trees, an editor wrote, "What was a few years ago deemed the impossible has happened." To the south, Ken Lilly-president of the Stanford University student body, star of its baseball team, candidate for the U.S. Olympic track team-was driving with two classmates through the late-night streets of San Jose when his car crashed into a telephone pole. Lilly and one of his buddies were badly hurt, but they would recover. The forty-gallon barrel of wine they'd been transporting would not. Its disgorged contents turned the street red.\ Across the country on that last day before the taps ran dry, Gold's Liquor Store placed wicker baskets filled with its remaining inventory on a New York City sidewalk; a sign read "Every bottle, $1." Down the street, Bat Masterson, a sixty-six-year-old relic of the Wild West now playing out the string as a sportswriter in New York, observed the first night of constitutional Prohibition sitting alone in his favorite bar, glumly contemplating a cup of tea. Under the headline GOODBYE, OLD PAL!, the American Chicle Company ran newspaper ads featuring an illustration of a martini glass and suggesting the consolation of a Chiclet, with its "exhilarating flavor that tingles the taste."\ In Detroit that same night, federal officers shut down two illegal stills (an act that would become common in the years ahead) and reported that their operators had offered bribes (which would become even more common). In northern Maine, a paper in New Brunswick reported, "Canadian liquor in quantities from one gallon to a truckload is being hidden in the northern woods and distributed by automobile, sled and iceboat, on snowshoes and on skis." At the Metropolitan Club in Washington, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt spent the evening drinking champagne with other members of the Harvard class of 1904.\ There were of course those who welcomed the day. The crusaders who had struggled for decades to place Prohibition in the Constitution celebrated with rallies and prayer sessions and ritual interments of effigies representing John Barleycorn, the symbolic proxy for alcohol's evils. No one marked the day as fervently as evangelist Billy Sunday, who conducted a revival meeting in Norfolk, Virginia. Ten thousand grateful people jammed Sunday's enormous tabernacle to hear him announce the death of liquor and reveal the advent of an earthly paradise. "The reign of tears is over," Sunday proclaimed. "The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs. Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and the children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent."\ A similarly grandiose note was sounded by the Anti-Saloon League, the mightiest pressure group in the nation's history. No other organization had ever changed the Constitution through a sustained political campaign; now, on the day of its final triumph, the ASL declared that "at one minute past midnight ... a new nation will be born." In a way, editorialists at the militantly anti-Prohibition New York World perceived the advent of a new nation, too. "After 12 o'clock tonight," the World said, "the Government of the United States as established by the Constitution and maintained for nearly 131 years will cease to exist." Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane may have provided the most accurate view of the United States of America on the edge of this new epoch. "The whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse," Lane wrote in his diary on January 19. "... Einstein has declared the law of gravitation outgrown and decadent. Drink, consoling friend of a Perturbed World, is shut off; and all goes merry as a dance in hell!"\ HOW DID IT HAPPEN? How did a freedom-loving people decide to give up a private right that had been freely exercised by millions upon millions since the first European colonists arrived in the New World? How did they condemn to extinction what was, at the very moment of its death, the fifth-largest industry in the nation? How did they append to their most sacred document 112 words that knew only one precedent in American history? With that single previous exception, the original Constitution and its first seventeen amendments limited the activities of government, not of citizens. Now there were two exceptions: you couldn't own slaves, and you couldn't buy alcohol.\ Few realized that Prohibition's birth and development were much more complicated than that. In truth, January 16, 1920, signified a series of innovations and alterations revolutionary in their impact. The alcoholic miasma enveloping much of the nation in the nineteenth century had inspired a movement of men and women who created a template for political activism that was still being followed a century later. To accomplish their ends they had also abetted the creation of a radical new system of federal taxation, lashed their domestic goals to the conduct of a foreign war, and carried universal suffrage to the brink of passage. In the years ahead, their accomplishments would take the nation through a sequence of curves and switchbacks that would force the rewriting of the fundamental contract between citizen and government, accelerate a recalibration of the social relationship between men and women, and initiate a historic realignment of political parties.\ In 1920 could anyone have believed that the Eighteenth Amendment, ostensibly addressing the single subject of intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices, soft-drink marketing, and the English language itself? Or that it would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage, and the creation of Las Vegas? As interpreted by the Supreme Court and as understood by Congress, Prohibition would also lead indirectly to the eventual guarantee of the American woman's right to abortion and simultaneously dash that same woman's hope for an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.\ Prohibition changed the way we live, and it fundamentally redefined the role of the federal government. How the hell did it happen?\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Last Call by Daniel Okrent Copyright © 2010 by Daniel Okrent . Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Prologue January 16, 1920 1\ Part I The Struggle 5\ 1 Thunderous Drams and Protestant Nuns 7\ 2 The Rising of Liquid Bread 24\ 3 The Most Remarkable Movement 35\ 4 "Open Fire on the Enemy" 53\ 5 Triumphant Failure 67\ 6 Dry-Drys, Wet-Drys, and Hyphens 83\ 7 From Magna Carta to Volstead 96\ Part II The Flood 115\ 8 Starting Line 117\ 9 A Fabulous Sweepstakes 128\ 10 Leaks in the Dotted Line 146\ 11 The Great Whiskey Way 159\ 12 Blessed Be the Fruit of the Vine 174\ 13 The Alcohol That Got Away 193\ 14 The Way We Drank 205\ Part III The War of The Wet and the Dry 225\ 15 Open Wounds 227\ 16 "Escaped on Payment of Money" 247\ 17 Crime Pays 261\ 18 The Phony Referendum 289\ Part IV The Beginning of the End, the End, and After 311\ 19 Outrageous Excess 313\ 20 The Hummingbird That Went to Mars 329\ 21 Afterlives, and the Missing Man 355\ Epilogue 373\ Acknowledgments 377\ Appendix: The Constitution of the United States of America 381\ Notes 399\ Sources 435\ Index 454

\ David OshinskyThough much has been written about Prohibition…Okrent offers a remarkably original account, showing how its proponents combined the nativist fears of many Americans with legitimate concerns about the evils of alcohol to mold a movement powerful enough to amend the United States Constitution…Okrent's description of the Prohibition era is a narrative delight.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Gary Krist…witty and exhaustive…Okrent…certainly doesn't ignore…crowd-pleasing anecdotes…But he brings to his account a breadth of scholarship that allows us to put the shenanigans in proper perspective. And while the book at times barrages the reader with more detail than is truly necessary, Okrent is never tedious for long. He also takes pains to debunk some of the apocrypha that, thanks to the carelessness of less diligent historians, has become part of the accepted lore of the age.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyDaniel Okrent has proven to be one of our most interesting and eclectic writers of nonfiction over the past 25 years, producing books about the history of Rockefeller Center and New England, baseball, and his experience as the first public editor for the New York Times. Now he has taken on a more formidable subject: the origins, implementation, and failure of that great American delusion known as Prohibition. The result may not be as scintillating as the perfect gin gimlet, but it comes mighty close, an assiduously researched, well-written, and continually eye-opening work on what has actually been a neglected subject.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalWhile the story of Prohibition (1919–33) is not suspenseful, since we know how this social experiment turned out, Okrent (former public editor, New York Times) helpfully fills in details, explanations, and lessons to be learned while supplementing the familiar story of how legislated temperance did not succeed. He mines archival and published sources and adds memories acquired through interviews and reference to previously unavailable private papers. Okrent emphasizes that the 18th Amendment was a long time coming, passed by the efforts of progressives, populists, nativists, and other morally motivated reformers. Temporarily ending the fifth-largest industry in America, Prohibition transformed the alcoholic beverage business as well as American culture generally. Okrent admits that, although Prohibition promoted criminality and hypocrisy, it did cut the rate of alcohol consumption. He book-ends his work with historical explications of Prohibition's enactment and its eventual demise owing to lack of both sufficient political will and enforcement funds. VERDICT While there are other Prohibition narratives, e.g., Michael Lerner's ably done Dry Manhattan, acknowledged by Okrent, this sprightly written and thoroughly annotated work is recommended for both the general reader, to whom it is directed, and the scholar.—Frederick J. Augustyn Jr., Library of Congress\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsBoth a rollicking recap of the Roaring '20s and a cautionary tale about how a government's attempts to legislate and monitor morality are nearly always doomed. Book- and magazine-publishing veteran Okrent (Public Editor #1: The Collected Columns (with Reflections, Reconsiderations, and Even a Few Retractions) of the First Ombudsman of The New York Times, 2006, etc.)-former editor-at-large of Time, Inc., and managing editor of Time and an editor at Knopf, Viking and Harcourt-joined forces early with filmmaker Ken Burns, and his new book will be prominently featured in a 2011 Ken Burns/Lynn Novick documentary about Prohibition. The author assembles a phenomenal cast of characters who emerged during Prohibition's conception, birth, swift life and death. Evangelist Billy Sunday, P.T. Barnum, Jack London, hatchet-wielding Carry Nation, Wayne Wheeler (of the Anti-Saloon League), Jane Addams, Warren G. Harding, Andrew Mellon, Eliot Ness, Al Capone, Andrew John Volstead and countless others strutted across the stage and then, frequently, disappeared. Okrent muses about the evanescent fame/notoriety of Wheeler, for example, who for a time made Senators tremble and was among the most powerful men in America-but who's heard of him now? The author skips around the country to examine the vast dimensions of the crime, corruption and plain disregard for the law that ensued when the 18th Amendment went into effect in January 1920. Liquor flowed in from Canada; entrepreneurs took drinkers on long Caribbean cruises; mom and pop got prescriptions for "medicinal" alcohol from physicians benefitting from kickbacks; racism and xenophobia reigned; Catholic churches and other religious institutions suddenlyneeded much more wine for rituals; and brewers and blenders tried near-beers and grape juices. In addition, the tax coffers emptied while gangsters bathed in liquidity. It took the Depression to help end it all-and the pervasive realization that only criminals were winning. Okrent's style is bracing and wry, his research is vast and impressive and his insight is penetrating. Intoxicating. Agent: Liz Darhansoff/Darhansoff, Verrill, Feldman Literary Agents\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn narrating his social and political chronicle of the 18th Amendment, Okrent competently brings a divergent host of characters--both “wet” and “dry”--to life including Mabel Walker Willebrandt, a trailblazing female attorney, law enforcement official, and earnest reformer who found herself surrounded by considerably less zealous colleagues in the Treasury Department, and Canadian distiller Sam Bronfman, who transformed his renegade operations into the Seagram’s beverage empire. Okrent takes pains not to fall into familiar Hollywood caricatures in portraying such well-known icons of the era as Al Capone and Joseph P. Kennedy. In his reading, Okrent turns down the familiar noise of the flappers and machine-gun fire--without stinting on color--for a more nuts and bolts perspective. A Simon & Schuster hardcover (Reviews, Jan. 11). (June)\ \ \ \ \ From the Publisher"This is history served the way one likes it, with scholarly authority and literary grace. Last Call is a fascinating portrait of an era and a very entertaining tale." \ —Tracy Kidder\ “Last Call is—I can't help it—a high, an upper, a delicious cocktail of a book, served with a twist or two and plenty of punch.”\ —Evan Thomas, Newsweek\ “A triumph. Okrent brilliantly captures the one glaring 'whoops!' in our Constitutional history. This entertaining portrait should stimulate fresh thought on the capacity and purpose of free government.”\ —Taylor Branch\ “This is a marvelous and lively social history, one that manages to be both scholarly and exciting. Okrent takes us through a period of American history unlike any other. Fair-minded, insightful, and amused, he has a command of the material that makes the journey rewarding at every sober step of the way. I loved this book.”\ —Lawrence Wright, author, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11\ “Daniel Okrent's Last Call is filled with delightful details, colorful characters, and fascinating social insights. And what a great tale! Prohibition may not have been a lot of fun, but this book sure is.”\ —Walter Isaacson\ “Daniel Okrent's Last Call fills a gaping void in American popular history that has been waiting for years to be filled, by providing a clear, sweeping, detailed and immensely readable account of Prohibition. His book is full of lively stories, incredible characters and fascinating research. It is, at once, great fun to read and solid history, a rare combination." –[trimmed quote still needsapproval]\ —Michael Korda, author of Ulysses S. Grant, Ike, and With Wings Like Eagles\ \ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewWhen Daniel Okrent kicks off Last Call, his sweeping history of Prohibition, by asking of the United States' 14-year alcohol ban, "How the hell did it happen?," you get the feeling you're in for a rollicking ride. And Okrent doesn't disappoint. The book, fast-paced and witty, includes enough fascinating details of this strange experiment to make you the star of your next cocktail party. There are some genuine laugh-out-loud moments, too, particularly in the ways people got around the ban, which lasted from 1920 to 1933. Take the Vino Sano Grape Brick, a dehydrated block of grape juice concentrate whose flavors included port, sherry, and burgundy and whose label warned consumers "to be sure not to add yeast or sugar, or leave it in a dark place, or let it sit too long before drinking it" because it just might ferment and become wine.\ But don't be fooled by how fun the book is: Last Call is a significant work of scholarship. Okrent, who was the first public editor of the New York Times, begins by establishing the context for the dry movement, describing the excessive drinking typical of the 19th century -- "in modern terms... the equivalent of 1.7 bottles of a standard 80-proof liquor per person, per week." He traces the early alliance between the temperance and suffrage movements -- many women agitating for the vote wanted to use it to shut down the saloons -- also weaving in the force of racist and nativist sentiment. One southern dry fretted about "drunken Negroes [pushing] white ladies off the sidewalks"; meanwhile, the immigrant composition of the political machines that controlled cities like New York and Chicago and that used saloons as their social and organizing centers was, Okrent writes, "an affront to the native Protestant's sense of his own prerogatives." While this big-tent coalition made passage of the Eighteenth Amendment politically feasible, it was made financially feasible by the passage of the income tax, which helped "break the federal addiction" to taxes on alcohol.\ Okrent's meticulous research brings new dimension to the enduring cultural images of the era. Sure, there were the storied speakeasies like New York's 21 Club, which benefited from Prohibition's underfunded, understaffed, and frequently apathetic enforcement. But there were also bootlegging rabbis who took advantage of an exemption for sacramental drink by organizing fake congregations through which they distributed wine and enriched themselves. The author shows how bootlegging, which began as largely local and nonviolent activity, was taken over by organized criminal enterprises, and he marvels at the "romantic glow" that has come to surround murderous gangsters like Al Capone.\ The onset of the Depression worked in favor of Prohibition's repeal -- all that alcohol tax money began to look pretty appealing again, as did the jobs that functioning breweries and distilleries would provide. While experts were certain that repeal would never happen (in 1930 the Eighteenth Amendment's author, Senator Morris Sheppard, declared, "There is as much chance of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment as there is for a hummingbird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail"), it actually happened very quickly. Okrent, who will appear in Ken Burns's upcoming PBS documentary on Prohibition, concludes that "in almost every respect imaginable, Prohibition was a failure." The one exception? Americans did drink less, and for decades afterward continued to do so. The fact that post-Prohibition alcohol consumption was slow to rise hints at a "central irony": repeal, bringing regulations that introduced closing hours, age limits, and Sunday blue laws, in fact "made it harder, not easier, to get a drink."\ --Barbara Spindel\ \ \