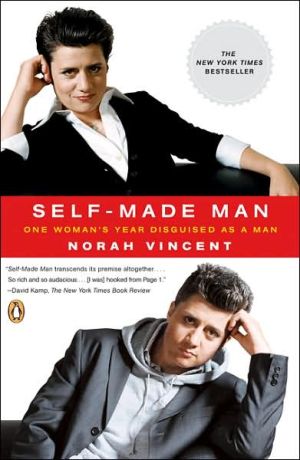

Self-Made Man: One Woman's Year Disguised as a Man

A journalist’s provocative and spellbinding account of her eighteen months spent disguised as a man\ Norah Vincent became an instant media sensation with the publication of Self-Made Man, her take on just how hard it is to be a man, even in a man’s world. Following in the tradition of John Howard Griffin (Black Like Me), Norah spent a year and a half disguised as her male alter ego, Ned, exploring what men are like when women aren’t around. As Ned, she joins a bowling team, takes a...

Search in google:

A journalist's provocative and spellbinding account of her eighteen months spent disguised as a man Norah Vincent became an instant media sensation with the publication of Self-Made Man, her take on just how hard it is to be a man, even in a man's world. Following in the tradition of John Howard Griffin (Black Like Me), Norah spent a year and a half disguised as her male alter ego, Ned, exploring what men are like when women aren't around. As Ned, she joins a bowling team, takes a high-octane sales job, goes on dates with women (and men), visits strip clubs, and even manages to infiltrate a monastery and a men's therapy group. At once thought- provoking and pure fun to read, Self-Made Man is a sympathetic and thrilling tour de force of immersion journalism. The Washington Post - Lily Burana While the side effects of Vincent's experiment are fascinating (including what happens when she reveals herself to be female and the negative impact on her psyche), it is her field reporting from Planet Guy that holds the most novelty. Self-Made Man will make many women think twice about coveting male "privilege" and make any man feel grateful that his gender burden is better understood.

Self-Made Man\ One Woman's Journey Into Manhood and Back Again \ \ By Norah Vincent \ Viking Adult\ ISBN: 0-670-03466-5 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Seven years ago, I had my first tutorial in becoming a man. \ The idea for this book came to me then, when I went out for the first time in drag. I was living in the East Village at the time, undergoing a significantly delayed adolescence, drinking and drugging a little too much, and indulging in all the sidewalk freak show opportunities that New York City has to offer.\ Back then I was hanging around a lot with a drag king whom I had met through friends. She used to like to dress up and have me take pictures of her in costume. One night she dared me to dress up with her and go out on the town. I'd always wanted to try passing as a man in public, just to see if I could do it, so I agreed enthusiastically.\ She had developed her own technique for creating a beard whereby you cut half inch chunks of hair from unobtrusive parts of your own head, cut them into smaller pieces, and then more or less glopped them onto your face with spirit gum. Using a small round freestanding mirror on her desk, she showed me how to do it in the dim, greenish light of her cramped studio apartment. It wasn't at all precise and it wouldn't have passed muster in the daylight, but it was good enough for the stage, and it would work well enough for our purposes in dark bars at night. I made myself a goatee and mustache, and a pair of baroque sideburns. I put on a baseball cap, loose-fitting jeans and a flannel shirt. In the full-length mirror I looked like a frat boy-sort of.\ She did her thing-which was more willowy and soft, more like a young hippie guy who couldn't really grow much of a beard-and we went out like that for a few hours.\ We passed, as far as I could tell, but I was too afraid to really interact with anyone, except to give one guy brief directions on the street. He thanked me as "dude" and walked on.\ Mostly though we just walked the streets of the Village scanning people's faces to see if anyone took a second or third look. But no one did. And that, oddly enough, was the thing that struck me the most about that evening. It was the only thing of real note that happened. But it was significant.\ I had lived in that neighborhood for years, walking its streets where men lurk outside of bodegas, on stoops and in doorways much of the day. As a woman, you couldn't walk down those streets invisibly. You were an object of desire or at least semiprurient interest to the men who waited there, even if you weren't pretty-that, or you were just another piece of pussy to be put in its place. Either way, their eyes followed you all the way up and down the street, never wavering, asserting their dominance as a matter of course. If you were female and you lived there, you got used to being stared down, because it happened every day and there wasn't anything you could do about it.\ But that night in drag, we walked by those same stoops and doorways and bodegas. We walked right by those same groups of men. Only this time they didn't stare. On the contrary, when they met my eyes they looked away immediately and concertedly and never looked back. It was astounding, the difference, the respect they showed me by not looking at me, by purposely not staring.\ That was it. That was what had annoyed me so much about meeting their gaze as a woman, not the desire, if that was ever there, but the disrespect, the entitlement. It was rude, and it was meant to be rude, and seeing those guys looking away deferentially when they thought I was male, I could validate in retrospect the true hostility of their former stares.\ But that wasn't quite all there was to it. There was something more than plain respect being communicated in their averted gaze, something subtler, less direct. It was more like a disinclination to show disrespect. For them, to look away was to decline a challenge, to adhere to a code of behavior that kept the peace among human males in certain spheres just as surely as it kept the peace and the pecking order among male animals. To look another male in the eye and hold his gaze is to invite conflict, either that or a homosexual encounter. To look away is to accept the status quo, to leave each man to his tiny sphere of influence, the small buffer of pride and poise that surrounds and keeps him.\ I surmised all of this the night it happened, but in the weeks and months that followed I asked most of the men I knew whether I was right, and they agreed, adding usually that it wasn't something they thought about anymore, if they ever had. It was just something you learned or absorbed as a boy, and by the time you were a man, you did it without thinking.\ After the whole incident had blown over, I started thinking that if in such a short time in drag I had learned such an important secret about the way males and females communicate with each other, and about the unspoken codes of male experience, then couldn't I potentially observe much more about the social differences between the sexes if I passed as a man for a much longer period of time? It seemed true, but I wasn't intrepid enough yet to do something that extreme. Besides it seemed impossible, both psychologically and practically, to pull it off. So I filed the information away in my mind for a few more years and got on with other things.\ Then, in the winter of 2003, while watching a reality television show on the A& E network, the idea came back to me. In the show, two male and two female contestants set out to transform themselves into the opposite sex-not with hormones or surgeries, but purely by costume and design. The women cut their hair. The men had theirs extended. Both took voice and movement lessons to try to learn how to speak and behave more like the sex they were trying to become. All chose new wardrobes, personas and names for their alter egos. The bulk of the program focused on the outward transformations, though the point at the end was to see who could pass in the real world most effectively. Neither of the men really passed, and only one of the women stayed the course. She did manage to pass fairly well, though only for a short time and in carefully controlled circumstances.\ But, as in most reality television programs, especially the American ones, nobody involved was particularly introspective about the effect their experiences had had on them or the people around them. It was clear that the producers didn't have much interest in the deeper sociologic implications of passing as the opposite sex. It was all just another version of an extreme make-over. Once the stunt was accomplished-or not-the show was over.\ But for me, watching the show brought my former experience in drag to the forefront of my mind again and made me realize that passing in costume in the daylight could be possible with the right help. I knew that writing a book about passing in the world as a man would give me the chance to explore some of the unexplored territory that the show had left out, and that I had barely broached in my brief foray in drag years before.\ I was determined to give the idea a try.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Self-Made Man by Norah Vincent Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Self-Made Man 1. Getting Started\ 2. Friendship\ 3. Sex\ 4. Love\ 5. Life\ 6. Work\ 7. Self\ 8. Journey's End Acknowledgments Author Interview

\ Lily BuranaWhile the side effects of Vincent's experiment are fascinating (including what happens when she reveals herself to be female and the negative impact on her psyche), it is her field reporting from Planet Guy that holds the most novelty. Self-Made Man will make many women think twice about coveting male "privilege" and make any man feel grateful that his gender burden is better understood.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe disguise that former Los Angeles Times op-ed columnist Vincent employed to trick dozens of people into believing her a man was carefully thought out: a new, shorter haircut; a pair of rectangular eyeglasses; a fake five o'clock shadow; a prosthetic penis; some preppy clothes. It was more than she needed. "[A]s I became more confident in my disguise... the props I had used... became less and less important, until sometimes I didn't need them at all," Vincent writes. Gender marking, she found, is more about attitude than appearance. Vincent's account of the year and a half she spent posing as a man is peppered with such predictable observations. To readers of gender studies literature, none of them will be especially illuminating, but Vincent's descriptions of how she learned, and tested, such chestnuts firsthand make them awfully fun to read. As "Ned," Vincent joined an all-male bowling league, dated women, worked for a door-to-door sales force, spent three weeks in a monastery, hung out in strip clubs and, most dangerous of all, went on a Robert Bly-style men's retreat. She creates rich portraits of the men she met in these places and the ways they behaved-as a lesbian, she's particularly good at separating the issues of sexuality from those of gender. But the most fascinating part of the story lies within Vincent herself-and the way that censoring her emotions to pass as a man provoked a psychological breakdown. For fans of Nickel and Dimed-style immersion reporting, this book is a sure bet. (Jan. 23) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ Library JournalVincent, formerly a Los Angeles Times syndicated columnist, has written a spellbinding, eyeopening personal narrative of 18 months spent "passing" as a man. She assumed the identity of "Ned," hiding her body within male clothing. Ned joined a men's bowling league, accompanied male acquaintances to strip joints, dated women, worked in a high-pressure male-dominated sales job, and participated in a ritual-laden men's sensitivity group. Late in the experiment, Ned moved to a monastery to experience a male environment without women. With intelligence and sensitivity, Vincent relates her experiences and surprising discoveries about the secrets and rites of male society and the daily fears and desires of individual men. She analyzes the dating scene from the male perspective, emphasizing the need for males to be able to deal with rejection 90 percent of the time and describing the toll this takes on the male ego. She highlights over and over again the communication disconnect between men and women and how their preconceived notions affect how they act toward one another. One of the big surprises of Vincent's account is that, after she revealed her identity to the men she had fraternized with and the women she had "dated," the people readily accepted her. An often humorous, incisive, and fascinating account that validates the conclusions of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus; for most public and academic libraries. [See Prepub Alert, LJ 9/15/05.]-Jack Forman, San Diego Mesa Coll. Lib. Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA fascinating, truly weird account of a female journalist who dresses in drag for 18 months in order to feel men's pain. What prompted Vincent, who notes that she is not a transsexual or a transvestite, to undertake a cross-dressing experiment as the 35-year-old nerdy Ned, who stinks at sports, is attractive to women, frequents strip clubs with new blue-collar buddies, brings a refreshing "emotional awareness" to a Catholic monastery and excels as a high-testosterone door-to-door salesman? Fascinated by the "unspoken codes of male experience," Vincent bets that becoming a man will allow her to "observe much more about the social differences between the sexes." With great seriousness she undertakes the creation of Ned's persona: Consulting a makeup artist, she fashions a credible five o'clock shadow (it gets a little nasty when she sweats); cuts her hair into a fade to emphasize a squarer jaw and dons rectangular glasses; wears a binding sports bra and pumps weights to bulk up her shoulders; and learns to modulate her already deep voice (men, she learns, don't talk in torrential prattle, but "lean back and pronounce with terse authority"). As Ned, she joins a working-class bowling team, who offer touching fatherly tips, and while she genuinely likes the men, revealing her identity to them after months of friendship seems a violent and traitorous blow. In chapters entitled "Friendship," "Sex," "Love," "Life," "Work" and "Self," Ned undergoes the rigors of male conditioning, though it is finally while participating in a men's-movement group that Vincent recognizes that most men in fact live in disguise-hiding rage, pain and shame. One of the curiouser books to appear of late-sure to attractattention.\ \