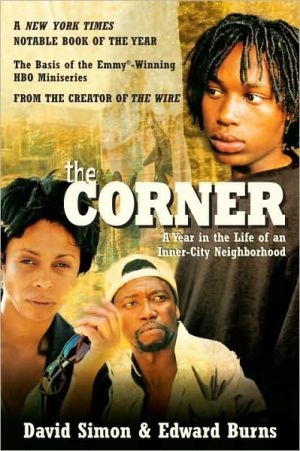

The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood

The crime-infested intersection of West Fayette and Monroe Streets is well-known—and cautiously avoided—by most of Baltimore. But this notorious corner's 24-hour open-air drug market provides the economic fuel for a dying neighborhood. David Simon, an award-winning author and crime reporter, and Edward Burns, a 20-year veteran of the urban drug war, tell the chilling story of this desolate crossroad.\ Through the eyes of one broken family—two drug-addicted adults and their smart, vulnerable...

Search in google:

Rare and unsparing, The Corner is a masterful account of a battle being waged—and lost—daily in neighborhoods across the nation. Here in tragic microcosm are the complexities and absurdities of the war on drugs. The human scale is devastating, as are the journalistic details. When horizons are truncated and hopelessness becomes institutionalized, society withers. On the corner, drugs offer the only response to unemployment and despair. Such clear-eyed truth is brutal. New York Times Book Review - Sara Mosle Brave, unblinkered and heartbreaking.

Gary McCullough nods, flustered, looking out at the Wabash Avenue courtroom for some better truth, or some better way of telling it. From the middle of the third bench, his mother covers her frown with both hands, terrified at the image of her son's life hanging in the balance. Gary catches her eye and tries to smile, then loses his train of thought.\ "It's like . . . judge, please, this is just crazy."\ Judge Bass, sensing the panic, tries to put the defendant at ease. "Take your time, Mr. McCullough, I'm listening to you. I just need you to speak louder."\ "Okay."\ "Go ahead."\ "All right."\ Where to begin? What to say? What to leave unsaid? So much to worry about now that all that foolishness with Ronnie is getting its day in court. Gary has taken a charge behind this nonsense; he's seen the bullpen on Eager Street because of it. And now, when he should be speaking up for himself and putting it all to rest, he's a stammering wreck. It's hell getting the God's honest truth out of your mouth when the damn thing is wrapped up in lies.\ "We had an argument . . . ," says Gary.\ True enough.\ ". . . about some money."\ Lie.\ "An' Ronnie, I mean, Veronica began yelling."\ True again.\ "So I asked her to leave . . ."\ Still true.\ ". . . but she kept cussin' me and telling me she wasn't going to go without the, ah, the, um . . . the money."\ The lie again.\ "Mr. McCullough, you'll have to speak up."\ "Um . . ."\ "You'll have to talk louder so I can hear you."\ Gary nods, agreeable. "She just wouldn't leave," he tells Judge Bass, "so I finally shoved her a little, toward the door, like. I didn't hit her, I just pushed her to get her out of the house."\ Truth, or close enough to it.\ "And she threw a brick at me . . ."\ Truth.\ "A brick?" asks Judge Bass.\ "And a knife," adds Gary.\ Lie. A home run swing from Gary McCullough.\ "She threw a knife at you?"\ "I was standing in the doorway."\ "What kind of knife?"\ "Kitchen kind. Had a big blade and all."\ The judge can't let that one go. He's looking up at the acoustic-tile ceiling, giving words to the thought running through the heads of everyone else in the courtroom.\ "Where did she get the knife?"\ Gary shrugs, wondering what that has to do with anything. He's sweating profusely, a prisoner inside his gray pinstripe church suit.\ "I mean," says the judge. "Did she have the knife on her or did she go and get the knife from somewhere? She didn't just find it lying in the street, did she?"\ Gary shrugs again, then scratches his ear, thinking about it. To look at him, to catch even a glimpse of the sincerity in his face, you'd think there might actually have been a knife involved. Who's to say? With Gary McCullough, a man far too honest about most things, the occasional lie always takes on a life of its own. Today, on a bright May morning, eight months after the fact, he truly believes Ronnie tossed a knife at him. If she had a knife, she surely would have.\ Judge Bass raises an eyebrow, then glances over at the assistant state's attorney, who lets the judge continue the redirect. "Do you know where the knife came from?" the judge asks Gary.\ "From Ronnie's hand. She threw it."\ Laughter breaks from the clustered humanity on the court benches. Even Judge Bass has to smile.\ "But you don't know where she got it."\ "Uh-uh."\ "Okay, go on."\ Go on, Mr. McCullough. Tell the tale as best you can. But leave out the part about the vials of heroin, the part where you wouldn't share a blast with Ronnie and she started to raise hell, calling you all kinds of names. By all means, mention the brick—the kitchen knife, even—but leave out the part where you ran out of the house afterward to confront her, grabbing her neck, and then shoving her down the sidewalk. Tell it in small pieces, as if it's a broken puzzle. Tell it the way you think they might want to hear it.\ "I didn't hit her," Gary says.\ That this case is now being played out in court is, in itself, an incredible thing. That it couldn't be stetted or nol-prossed or reduced to some unsupervised probation is testament only to the current political imperatives. Gary and Ronnie both had come to court today certain that they could make the thing go away; Ronnie would decline to testify and the prosecutors would shrug and toss the casefile into a tall stack of district court dismissals.\ But no. It wasn't just the usual Western District prosecutor in court today, but an assistant state's attorney from downtown somewhere. And this case could not be dismissed as everyone desired because of its status as a domestic violence complaint. In the eyes of the government, Ronnie Boice is no longer the quick-thinking, game-running, syringe-switching wonder of Fayette Street. Consciousness has been sufficiently raised so that now, by a policy new to the prosecutor's office, all domestic assault cases are fully pursued—even when a wife or girlfriend has attempted to back away from her original statement. For today at least, Ronnie Boice will be representing battered womanhood.\ It's a noble effort by the state's attorney's office, a worthy strategy in those cases in which abused women are too frightened or intimidated to testify against their assailants. In the present case, however, the new policy is a source of unintentional hilarity.\ Ronnie never had any intention of pursuing the case; she just wanted Gary to know that what was his—coke, dope, or both—was hers as well. But now she'll have to testify or risk being charged with obstructing justice. And if she tells the truth on the stand—tells them that it was a shoving match over a blast—well, that will mean a charge of false statement or perjury for her original complaint. When Gary declined a plea offer of six months in jail followed by spousal abuse counseling, the court trial was the only option left.\ "Why would Miss Boice make a complaint against you if you didn't hit her?" asks the prosecutor, picking up the redirect.\ "I don't know," says Gary, looking genuinely hurt.\ "But you're saying she made all this up?"\ "Yes."\ "Why would she do that?"\ Gary's mouth gapes open, then shuts. He wants to say it. He has to fight himself not to say it: Why do you think, fool? She wanted my blast. She wanted my blast and I said no and so she called the police. If Gary told them that, if he let it fall from his lips in the Western District court, everything would make sense. And neither the judge nor the prosecutor would bother to bring any charge from the admission of drug use, not in Baltimore, anyway. But Gary can't see that; he keeps his secret.\ Ronnie, too. Just before Gary took the witness stand in his own defense, Ronnie gave her own grudging testimony. Questioned by the prosecutor, she made no mention of the blast, choosing instead to pretend that the argument was about Gary giving his attentions to some other girl. In sharp contrast to Gary's later panic, his girl managed to thread the needle masterfully. Droll from the witness stand, her eyes bouncing between Gary at the defense table and his mother three rows back, she destroyed the case without directly contradicting her original complaint. No, she did not throw a brick. No, there was no knife. Yes, Gary did shove her, and later, on the sidewalk, he slapped her. But yeah, well, she did push him, too. In fact, she might have pushed him first, now that she thinks on it.\ "Mutual combat," said Judge Bass, looking at the state's attorney in bland resignation. Once Ronnie left the witness stand, it only remained for Gary to make some kind of denial and now, testifying in his own defense, he manages that much.\ "Your honor. I didn't hit her. I swear."\ Not guilty. The Western District prosecutor nods agreeably, then tosses the file into the discard pile. The domestic violence specialist from downtown looks crestfallen.\ Out in the courthouse hallway, the victory celebration is brief and ugly. Gary walks out with his mother on his arm; Ronnie, right behind him, with her own mother, who apparently didn't want to miss her daughter's big day in court.\ "Well," ventures Roberta McCullough, "at least that's over."\ "Over and done with," agrees Miss Sarah.\ "But I don't think our childrens should be together," Miss Roberta says, eyeing Ronnie fretfully. "They're just not good for each other. They don't do each other any good."\ Ronnie's mother bristles. "What the hell you mean by that?"\ Hands braced against her hips, she stares down at the smaller woman with contempt. Gary is behind his mother, looking at Ronnie in horror. Ronnie is smiling.\ "I just mean . . ."\ "They'se grown-up children," shouts Miss Sarah, performing for the entire building. "You can't tell them what to do, you ol' bitch cow."\ Roberta McCullough's small frame seems to warp from the verbal assault, her eyes falling to the floor. Shaking, she holds one hand to her heart; Gary takes the other and tries to lead her to the stairs.\ "Who the hell you think you is?" shouts Ronnie's mother. "Tell my daughter what she can and can't do. You can go an' fuck yo'self, you ol' cow."\ From the top of the stairs, Gary helps his stricken mother to the rail, then looks back over his shoulder to see Ronnie and her mother following. Miss Sarah keeps bellowing insults; Ronnie is behind her, smiling so wickedly that Gary realizes that this is part of the price, that Ronnie—having known that his mother would be there for him—had contrived to bring her own mother to the show.\ "You think you so high and mighty," yells Miss Sarah. "Your son ain't no better than my daughter."\ The words echo down the stairs. Without turning, Miss Roberta falls back on the grace that she knows: "I'll pray for you," she tells her adversary. "That's all I can do."\ "Don't need your got-damn prayers, bitch."\ They leave the courthouse separately: Gary, consoling his mother, promising to have nothing more to do with Ronnie or her family; Ronnie, heading to Lafayette Market with the matriarch of the Boice clan, the two of them reliving the hallway battle in all its detail.\ The episode is enough to keep Gary from Ronnie all that night and the next day. He runs the streets telling himself that nothing—no caper, no blast, no game—will be enough to subject his mother to anything like that again. And it is true that Gary loathes nothing so much as the idea that his life is bringing grief to his mother.

\ From the PublisherPraise for The Corner:\ "The Corner is an intimate, intense dispatch from the broken heart of urban America. It is impossible to read these pages and not feel stunned at the high price, in human potential, in thwarted aspirations, that simple survival on the streets of West Baltimore demands of its citizens. An important document, as devastating as it is lucid."\ —Richard Price, author of Clockers\ "The Corner is a remarkable book—very tough, very demanding, very rewarding. Some of it is brutal and all of it is heartbreaking. As a reporter, I can only stand back and admire David Simon and Edward Burns for an amazing piece of reportage. To be there for an entire year, to make sense of random events and a list of characters long enough to make Charles Dickens envious, and to write coherently—it's a breathtaking achievement. And they manage to make West Baltimore as much a character as any of the flesh-and-blood people in the book."\ —Glenn Frankel, author of Beyond the Promised Land\ "If you want to understand street-corner life in the inner city, you should read The Corner, an amazingly intimate, detailed work of reporting that makes human and vivid a world that outsiders ordinarily are forced to learn about through statistics, sound bites, and stereotypes."\ —Nicholas Lemann, author of The Promised Land\ \ \ \ \ \ Sara MosleBrave, unblinkered and heartbreaking. \ — New York Times Book Review\ \ \ LynchThe Corner is set in West Baltimore, part of a city with the highest rate of drug-related arrests in the country. Metaphorically, though, the intersection of Fayette and Monroe Streets is replicated across America, in every urban neighborhood, and is encroaching on every Main Street.\ The cast is varied, but nearly all are consumed by the economic wasteland of their environs, and by the siren, escapist call of drugs. At the heartbreaking core of the story is 15-year-old DeAndre McCullough, a prototypical adolescent in the drug-drenched world of the corner, dealing, skipping school, fronting a tough image that's about to stick. DeAndre's life bends all the classic theories of a young male forced to raise himself in the fatherless world of the ghetto. In fact, DeAndre's parents are all too present, both of them addicted to the blast, scheming and stealing from the moment they awaken until they finally crash.\ Gary McCullough, DeAndre's father, once rose to success as a businessman, only to be lured back to the corner. The cravings counter his inherent decency, today's fix taking precedence over yesterday's conscience. So while Gary still sees the world's possibilities, he is even more a slave to the snake that wakens in his belly every morning, hungry for the blast and full of venom without it.\ Fran McCullough, DeAndre's mother, has no illusions. She is of the corner. But her awareness of self exceeds any pity for her ex-husband, Gary, whose gentle and moral spirit allows him to be victimized again and again by all, especially Fran.\ Other players infuse the narrative. Shuffling down the block, working to earn his cut, Fat Curt and his bloated limbs testify to years of substance abuse. Rita, the "nurse" at the local shooting gallery, is an expert at finding a vein in rotting arms, including her own; as payment, she shares her patients' stash.\ At the other end of the spectrum is Ella, who believes that the recreation center she runs provides a haven for the neighborhood's children, all of whom are "at risk." Alas, one woman cannot save an entire community and fill the vacuum created by years of neglect. That someone ransacks the meager contents of the rec center is telling; that one or more of Ella's kids might have had a hand is debilitating. Saddest and most forgotten of all is DeRodd, seven years old and DeAndre's half brother, whose desire to watch "Barney" earns him a smack in the head.\ The corner has become its own ecosystem, "as complex as any natural world, as distinct and separate from the middle-class experience as can be imagined." And what invests The Corner as a document of truth is the journalistic devotion of the authors, David Simon and Edward Burns; their revelations spring from direct observation of these lives. Their motivation is a heightened understanding, not personal ideology. And just when despair threatens to consume the reader, too, the authors shift to a macroperspective, or add a note of compassion.\ "How do we bridge the chasm?" The authors ask. "How do we begin to reconnect with those now lost to the corner world? We've got to begin to think as Gary McCullough thinks when he's flat broke and sick with desire, crawling through some vacant row house in search of scrap metal. Or live, for a moment at least, as Fat Curt lives when he's staggering back and forth between corner and shooting gallery."\ Lord knows, there have been examinations of inner-city violence and studies of the drug culture, gangs, and teenagers having babies. All have a "tsk-tsk" quality or a "look at where society is headed" backdrop. The Corner is much more powerful and important than those because the authors accord respect to the reality of the lives they recount. After all, movies have been made, articles have been written, and even Bill Moyers's son has fallen victim to drug addiction resulting in a detailed report on "the hijacked brain." The authors refuse to join the cynical head-shaking about the drug world.\ However, in every drug documentary there comes the mention of "rock bottom," that place where every addict must find him self before he turns his life around. Well, Simon and Burns decided to visit the people who are born to and reside in rock bottom. For these people, rock bottom is death. But before they die, they live a life with purpose, meaning, and dedication -- to getting high.\ Through these harrowing yet highly readable 500-odd pages, the authors have achieved more than society could ask. While neither are novices to these experiences -- Simon is the author of the award-winning book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets , which inspired the NBC-TV series, and Burns spent 20 years with the Baltimore Police Department before embarking on a career as a teacher in the city's public schools -- their lingering naivete can be felt in every revelation, every break in the action where they put things into perspective for the reader and for themselves.\ And The Corner has many moments of brilliant abstract analysis, such as the phenomenon of the "paper bag." Who hasn't seen men in the parks drinking some alcoholic beverage out of a paper bag? Magically, the illegality of public drinking is transformed: "When the first wino dropped the first bottle of elderberry into the first paper bag -- and a moment of quiet genius it was -- the point was moot. The paper bag allowed the smoke hounds to keep their smoke, just as it allowed the beat cop a modicum of respect. In time, the bag was institutionalized as a symbol; to drink without it was to insult the patrolman and risk arrest, just as it was a violation of the tacit agreement for the cop to ignore the bag and humble anyone employing it."\ The subtlety of the paper bag gives way to the irony of the caper, the everyday burglaries, robberies, and stick-ups that pay for the drugs: "All that effort not to get caught, and then, when they did get caught, it hardly mattered. All that cloak and dagger and a half-hour later they're walking a refrigerator down Baltimore Street, in broad daylight."\ We who are African American, even if we have three degrees from Harvard, remain only two-degrees-of-separation from someone living on the corner. We know about much of what's revealed in these pages. But we will revel nonetheless that we are finally reading the truth. These two writers, despite their outsider status as whites, came to understand things that are very intricate to the ecosystem. They even manage to explain what keeps the ecosystem so complete, so fertile, something many of us know but will be glad they're telling everyone else: "On Fayette Street, the standing assumption is that any place in America without bricks and pavement and black people is, by definition, a playground for sheet-wearing, pickup-truck-wrecking, get-a-rope rednecks."\ Would you leave?\ While the authors are aware that the pervasiveness of drug addiction among the women of the inner city is a new phenomenon, they fail to realize the absolutely devastating impact of that fact. That great R&B group, the Intruders, told us back in the '70s that they'll always love their mama. Remember? They couldn't understand "how she made it through the week because she never got a good night's sleep." She was working all the time. And Pop was always gone; out drinking somewhere. Addicted to liquor. Well, the corners have lost mama. She's addicted. She's way too young. She's no longer strong.\ Where are we in all this? Regardless of color, and from the perspective of the corner, we're the taxpayers; conspicuously missing from the corner community. Voting without truth. Well, the truth is finally on paper. And it shall set us all free. But we've got work to do.\ --Marlene Connor Lynch\ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ In the authors' note, Simon (Homicide) and Burns, a retired patrolman and detective with the Baltimore Police Department, encapsulate their year-long (1992-1993) experience on a west Baltimore street corner interviewing drug addicts and watching children grow up too fast. They masterfully present a theater of the drug war as they follow four generations of the McCullough family, concentrating on 15-year-old DeAndre, who attempts to rise above the mistakes of his heroin- and cocaine-addicted parents but fails to escape the pressures of the street. Yet his story allows exploration of other issues, such as the history of the corner's drug activities and the attitudes of the police, the social workers and the high-school teachers who have all but lost hope for the area's children. Part family neighborhood portrait, part political-social analysis, the book conveys the feeling of helplessness of those who awake every morning thinking only of their "next blast" and the arrogance of those who condemn them for it. The loss of innocence chronicled here is summed up by a line from one of DeAndre's poems: "Hungry for knowledge, but afraid to eat."\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis portrayal of a year in drug-crazed west Baltimore will satisfy neither readers looking for a perceptive witness to the urban crisis nor those in search of social analysis. Simon (Homicide), a crime reporter, and Burns, a Baltimore police veteran and public school teacher, mask their presence in the scene with an omniscient style that strains credibility, and the chronological framework blunts the impact of their most compelling themes. The authors salute the courageous but futile efforts of individual parents, educators, and police officers but deny the possibility of a social solution to the devastation they acknowledge is rooted in social policy. A more compelling account is Our America: Life and Death on the South Side of Chicago, based on interviews conducted by 13-year-old public housing residents LeAlan Jones and Lloyd Newman in 1993. For larger public libraries. \ —Paula Dempsey, Loyola University, Chicago\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsIn an accomplished and vivid piece of reporting, Edgar Award winner Simon ("Homicide", 1991) and retired detective Burns team up to document the struggles of a cross-section of the Baltimore drug subculture.\ By the mid-1990s, Baltimore had the highest rate of intravenous drug use in the country. Simon and Burns follow their West Baltimore subjects throughout the year 1993. Alternating bits of social history and commentary with intimate details of the corner inhabitants' lives, Simon and Burns focus primarily on three members of a single family, the McCulloughs: Gary, a junkie who had it all and lost it; his ex-wife, Fran, a user who nonetheless does her best to raise her boys; and DeAndre, a 15-year-old hustler for whom flash and brand name—whether Timberland, Nike, or Hilfiger—are all. The main players move forward, then backward, in fits and starts. For most of the others the reader meets, a steady downward trajectory describes their existence. The authors liken the corner heroin and crack market to a fast-food emporium, a place of "sustenance," no less elemental to the inner cities of America than the watering hole is to the natural world. Against the fact of relentless addiction and the commerce of the drug marketplace, Simon and Burns argue, the drug war stands as a "useless and unnecessary brutalization." The authors don't claim to have the answers to eradicating the corner drug culture that thrives throughout America's cities. But their portrait suggests that any solution must be grounded in compassion for, and understanding of, a group of individuals who are wrongly seen by much of America as somehow less than human.\ Having gained the trust of their subjects, and with almost novelistic skill in bringing them (especially DeAndre) to life, Simon and Burns offer us a first step to achieving that understanding.\ \ \