The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression

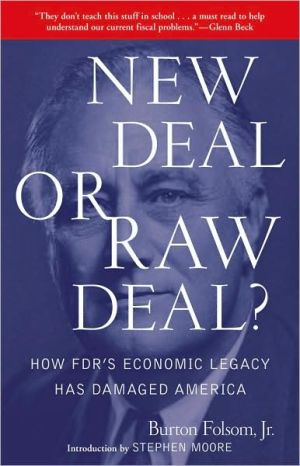

In The Forgotten Man, Amity Shlaes, one of the nation's most-respected economic commentators, offers a striking reinterpretation of the Great Depression. She traces the mounting agony of the New Dealers and the moving stories of individual citizens who through their brave perseverance helped establish the steadfast character we recognize as American today.

Search in google:

It's difficult today to imagine how America survived the Great Depression. Only through the stories of the common people who struggled during that era can we really understand how the nation endured. These are the people at the heart of Amity Shlaes's insightful and inspiring history of one of the most crucial events of the twentieth century. In The Forgotten Man, Amity Shlaes, one of the nation's most respected economic commentators, offers a striking reinterpretation of the Great Depression. Rejecting the old emphasis on the New Deal, she turns to the neglected and moving stories of individual Americans, and shows how through brave leadership they helped establish the steadfast character we developed as a nation. Some of those figures were well known, at least in their day Andrew Mellon, the Greenspan of the era; Sam Insull of Chicago, hounded as a scapegoat. But there were also unknowns: the Schechters, a family of butchers in Brooklyn who dealt a stunning blow to the New Deal; Bill W., who founded Alcoholics Anonymous in the name of showing that small communities could help themselves; and Father Divine, a black charismatic who steered his thousands of followers through the Depression by preaching a Gospel of Plenty. Shlaes also traces the mounting agony of the New Dealers themselves as they discovered their errors. She shows how both Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt failed to understand the prosperity of the 1920s and heaped massive burdens on the country that more than offset the benefit of New Deal programs. The real question about the Depression, she argues, is not whether Roosevelt ended it with World War II. It is why the Depression lasted so long. From 1929 to 1940, federal intervention helped to make the Depression great in part by forgetting the men and women who sought to help one another. Authoritative, original, and utterly engrossing, The Forgotten Man offers an entirely new look at one of the most important periods in our history. Only when we know this history can we understand the strength of American character today. Publishers Weekly This breezy narrative comes from the pen of a veteran journalist and economics reporter. Rather than telling a new story, she tells an old one (scarcely lacking for historians) in a fresh way. Shlaes brings to the tale an emphasis on economic realities and consequences, especially when seen from the perspective of monetarist theory, and a focus on particular individuals and events, both celebrated and forgotten (at least relatively so). Thus the spotlight plays not only on Andrew Mellon, Wendell Wilkie and Rexford Tugwell but also on Father Divine and the Schechter brothers—kosher butcher wholesalers prosecuted by the federal National Recovery Administration for selling "sick chickens." As befits a former writer for the Wall Street Journal, Shlaes is sensitive to the dangers of government intervention in the economy—but also to the danger of the government's not intervening. In her telling, policymakers of the 1920s weren't so incompetent as they're often made out to be—everyone in the 1930s was floundering and all made errors—and WWII, not the New Deal, ended the Depression. This is plausible history, if not authoritative, novel or deeply analytical. It's also a thoughtful, even-tempered corrective to too often unbalanced celebrations of FDR and his administration's pathbreaking policies. 16 pages of b&w photos. (June 12)Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information

The Forgotten Man\ A New History of the Great Depression \ Chapter One\ The Beneficent Hand\ January 1927\ Average unemployment (year): 3.3 percent\ Dow Jones Industrial Average: 155\ Floods change the course of history, and the Flood of 1927 was no exception. When the waters of the Mississippi broke through banks and levees that spring, the disaster was enormous. A wall of water pushed down the river, covering the area where nearly a million lived. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover raced to Memphis and took command. Hoover talked railroads into transporting the displaced for free and carrying freight at a discount. He commandeered private outboard motors and built motorboats of plywood. He urged the people who were not yet flooded out, such as the population around the Bayou des Glaises levee, to evacuate early, then rescued with the trains those tens of thousands who had ignored his warning. He helped the Red Cross launch a fund drive; within a month the charity had already collected promises of more than $8 million, an enormous figure for the time.\ Several hundred thousand ended up in new refugee camps, many planned, right down to the latrines, by Hoover and his team. Hoover asked governors of each state to name a dictator of resources—he used the word "dictator"—and the governors complied. The dictators then managed the dysentery and the hunts for the missing along the floodwaters in their states hour by hour. He and the Red Cross sent the refugees to concentration camps—a phrase not so freighted then as it is today—at Vicksburg, Delta, and Natchez. One hundred thousand blankets from army warehouseswere shipped to warm the refugees.\ Things felt calmer on Hoover's watch. By mid-May, though the flooding was far from over, the anecdotes began to compete in the news with the reports of tragedy. Northerners read in Time magazine that a town called Waterproof, Louisiana, had not proven waterproof, and that its switchboard operators were still working—albeit from new posts, high up above the waters, on scaffolding. Not far from Memphis, Tennessee, bootleggers had also set up shop on high, in treetops. New babies were receiving flood names—Highwater Jones, Overflow Johnson. Now from Memphis, now from Little Rock, now from the Sugar Bowl, the itinerant flood manager, Hoover, wired or broadcast his analyses of the meaning of the disaster. Such flooding, he said, "is a national problem and must be solved nationally and vigorously." But the commerce secretary also spent a lot of time reassuring. The waters might hide the land, the crops might be lost, but the mood was now hopeful. More than any single figure, Hoover was succeeding in making Americans feel that the South would be all right again.\ Hoover was already so famous that his name was a verb—to Hooverize, after the efforts in food rationing that he had led from a post as Washington's food administrator at the end of World War I. Americans recalled that he had led the humanitarian drive to feed occupied Belgium during the war. Now Hoover had outdone himself—and on a home territory whose geographic area covered more than Belgium's. What the public liked about Hoover was their sense of him as guardian, that he would protect them and what they had. If Hoover could win the presidential election the following year, then he might hold back whatever waters of adversity threatened. He was a Republican, like the sitting president, Calvin Coolidge. He would pick up where Coolidge left off—though he might update things, for everyone knew that Hoover, a mining engineer, could do amazing things with technology. One of Hoover's neatest feats—and he pulled it off right around the time of the flood—was to acquaint the public with an early version of television. "Herbert Hoover made a speech in Washington yesterday afternoon. An audience in New York heard and saw him," the New York Times wrote in awe, adding that Hoover had "annihilated" geographic distance and commenting in a headline: "Like a Photo Come to Life." It was not yet modern television but wired images and the telephone combined. Still, the idea took hold in the minds of the reporters. Under Hoover, it was easy to believe that the 1920s were merely the American beginning.\ The idea of philosophical continuity from Coolidge to Hoover seemed ironic to one man: Calvin Coolidge himself. The two were party allies. Hoover had loyally campaigned for Coolidge in 1924—indeed, had helped to defeat a Coolidge opponent in 1924 in California to clear the Republican presidential nomination for Coolidge. But Coolidge did not especially like Hoover. In the very period when the Mississippi waters were rushing, in fact, Coolidge's press spokesman had taken an explicit shot at Hoover, telling reporters that the commerce secretary would not be considered for the job opening if the secretary of state happened to retire.\ The differences between the men had started with small things. Hoover was a fly fisherman. Coolidge fished with worms. Hoover liked the microphone. Coolidge shied away from it. After a landslide presidential victory in 1924 Coolidge had sent a clerk to read aloud his State of the Union address. Hoover ignored politics for the first thirty-five years of his life. Coolidge held his first office, that of city council member in Northampton, Massachusetts, at the age of twenty-eight, and had rarely been out of government since. Hoover was a mining engineer; Coolidge was a country lawyer. Hoover was a worldly American, a blend of regions and cities, the most successful in his field of his generation. He believed in the Anglo-American gold standard, not only because it had made him rich but because he had seen firsthand how it kept the world running, like a grandfather clock. Coolidge was a pure New Englander who seemed to re-create New England wherever he went. The very concept of "overseas" was a bit vague to Coolidge. The typical Republican of his day, he supported tariffs in the belief that they strengthened the United States. His failure to recognize the consequences of his policies, both abroad and for his country, was his greatest shortcoming.\ The Forgotten Man\ A New History of the Great Depression. Copyright © by Amity Shlaes. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold.

\ Paul Volcker"Amity Shlaes’s fast-paced review of the [Depression] helps enormously in putting it all in perspective."\ \ \ \ \ Peggy Noonan"The Forgotten Man is an epic and wholly original retelling of a dramatic and crucial era. There are many sides to the 1930’s story, and this is the one that has largely been lost to history. Thanks to Amity Shlaes, now it’s been re-found."\ \ \ Paul Johnson"Amity Shlaes is among the most brilliant of the young writers who are transforming American financial journalism."\ \ \ \ \ Harold Evans"The Forgotten Man is an incisive and controversial history of the Great Depression that challenges much of the received wisdom."\ \ \ \ \ William Kristol"Shlaes’s account of The Great Depression goes beyond the familiar arguments of liberals and conservatives."\ \ \ \ \ Clive Crook"Captivating. . . . Illuminating. . . . The Forgotten Man is an engaging read and a welcome corrective to the popular view of Roosevelt and his New Deal. . . . A refreshingly critical approach to Franklin Roosevelt’s policies."\ \ \ \ \ Grover G. Norquist"The Forgotten Man by Amity Shlaes will forever change how America understands the causes of the Depression and FDR’s policies that prolonged it for a decade."\ \ \ \ \ The American Spectator"Entertaining, illuminating, and exceedingly fair. . . . A rich, wonderfully original, and extremely textured history of an important time.\ \ \ \ \ The Wall Street Journal"A well-written and stimulating account of the 1930s and its often dubious orthodoxies. . . . Ms. Shlaes rightly reminds us of the harmful effect of Rooseveltian activism and class-warfare rhetoric."\ \ \ \ \ National Review"The finest history of the Great Depression ever written. . . . Shlaes’s achievement stands out for the devastating effect of its understated prose and for its wide sweep of characters and themes. It deserves to become the preeminent revisionist history for general readers. . . . Her narrative sparkles."\ \ \ \ \ The New York Review of Books"Amity Shlaes tells the story of the Depression in splendid detail, rich with events and personalities. . . . Many of Shlaes’s descriptions make genuinely delightful reading."\ \ \ \ \ Arthur Levitt"I could not put this book down. Ms. Shlaes timely chronicle of a fascinating era reads like a novel and brings a new perspective on political villains and heros—few of whom turn out to be as good or bad as history would have us believe."\ \ \ \ \ George F. Will"Americans need what Shlaes has brilliantly supplied, a fresh appraisal of what the New Deal did and did not accomplish."\ \ \ \ \ Mark Helprin"The Forgotten Man offers an understanding of the era’s politics and economics that may be unprecedented in its clarity."\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThis breezy narrative comes from the pen of a veteran journalist and economics reporter. Rather than telling a new story, she tells an old one (scarcely lacking for historians) in a fresh way. Shlaes brings to the tale an emphasis on economic realities and consequences, especially when seen from the perspective of monetarist theory, and a focus on particular individuals and events, both celebrated and forgotten (at least relatively so). Thus the spotlight plays not only on Andrew Mellon, Wendell Wilkie and Rexford Tugwell but also on Father Divine and the Schechter brothers—kosher butcher wholesalers prosecuted by the federal National Recovery Administration for selling "sick chickens." As befits a former writer for the Wall Street Journal, Shlaes is sensitive to the dangers of government intervention in the economy—but also to the danger of the government's not intervening. In her telling, policymakers of the 1920s weren't so incompetent as they're often made out to be—everyone in the 1930s was floundering and all made errors—and WWII, not the New Deal, ended the Depression. This is plausible history, if not authoritative, novel or deeply analytical. It's also a thoughtful, even-tempered corrective to too often unbalanced celebrations of FDR and his administration's pathbreaking policies. 16 pages of b&w photos. (June 12)\ Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information\ \ \ \ \ Forbes MagazineMany histories have been written about the Great Depression, the most searing economic cataclysm this country--and most of the world--has ever endured. Its most disastrous result, of course, was facilitating the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. But Amity Shlaes' new book stands head and shoulders above previous efforts in two profound, insightful ways. (23 Jul 2007)\ —Steve Forbes\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalRevisionist history from Bloomberg syndicated columnist Shlaes, who argues that federal intervention helped prolong the Great Depression. Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsShlaes (The Greedy Hand, 1999, etc.), a senior visiting fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a columnist at Bloomberg, brings to the Great Depression a flair for revealing anecdotes and a debater's moxie that slides into contrarianism. According to the author, from the Great Crash of 1929 until 1940, government intervention made the Depression an unprecedented national calamity. While liberal historians unfavorably contrast Herbert Hoover with Franklin Roosevelt, Shlaes takes the former engineer to task for a similarity to his successor: an overestimation of the value of government planning. The result: the end of sizable gains, courtesy of tax-cutting policies, under Presidents Harding and Coolidge. All of this requires revisionism so massive that Shlaes' powers of persuasion become as hit-or-miss as the liberal programs she criticizes. She is at her best in detailing the decade-long disillusionment of a group of academics, journalists, trade-union leaders and liberal activists who sailed to the U.S.S.R. in 1927 to observe communism in action, including future FDR adviser Rexford Guy Tugwell, economist and future senator Paul Douglas and ACLU founder Roger Baldwin. Her profile of the Schechters-a pro-Roosevelt family of butchers who successfully overturned the National Industrial Recovery Act before the Supreme Court-demonstrates her point that the "forgotten man" was really the small businessman trying to survive without government aid. But Shlaes' other examples suggest that it was the type-rather than the fact-of government intervention that was the real problem in the 1930s. The Smoot-Hawley tariff signed by Hoover, for instance, deprived businesses of foreign markets, butFDR's Securities and Exchange Commission stabilized the economy. Equally problematic, Shlaes' heroes come largely unblemished. While noting FDR's politically motivated tax prosecution of Andrew Mellon, Treasury Secretary during the 1920s boom, she underplays Mellon's culpability on conflict-of-interest charges. Plucky, intellectual combat, but Shlaes neglects to counter the most telling arguments about GOP responsibility for the Depression. Agent: Sarah Chalfant/Wylie Agency\ \