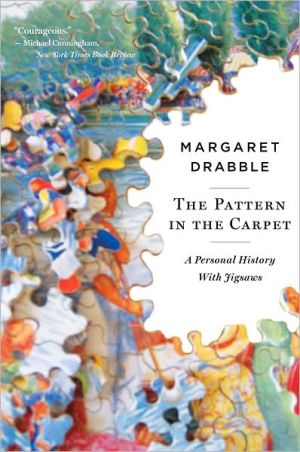

The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal History with Jigsaws

The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal History with Jigsaws is an original and brilliant work. Margaret Drabble weaves her own story into a history of games, in particular jigsaws, which have offered her and many others relief from melancholy and depression. Alongside curious facts and discoveries about jigsaw puzzles—did you know that the 1929 stock market crash was followed by a boom in puzzle sales?—Drabble introduces us to her beloved Auntie Phyl, and describes childhood visits to the...

Search in google:

The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal History with Jigsaws is an original and brilliant work. Margaret Drabble weaves her own story into a history of games, in particular jigsaws, which have offered her and many others relief from melancholy and depression. Alongside curious facts and discoveries about jigsaw puzzles—did you know that the 1929 stock market crash was followed by a boom in puzzle sales?—Drabble introduces us to her beloved Auntie Phyl, and describes childhood visits to the house in Long Bennington on the Great North Road, their first trip to London together, the books they read, and the jigsaws they completed. She offers penetrating sketches of her parents, siblings, and children, and shares her thoughts on the importance of childhood play, on art and writing, and on aging and memory. And she does so with her customary intelligence, energy, and wit. This is a memoir like no other. The Barnes & Noble Review Margaret Drabble readily admits that The Pattern in the Carpet is an eccentric hybrid of a book, a mix of personal memoir and a history of the jigsaw puzzle. When her husband, biographer Michael Holroyd, was fighting advanced cancer, she found she could stave off depression and panic by passing "a painless hour or two, assembling little pieces of cardboard into a preordained pattern, and thus regain an illusion of control."

Foreword\ This book is not a memoir, although parts of it may look like a memoir. Nor is it a history of the jigsaw puzzle, although that is what it was once meant to be. It is a hybrid. I have always been more interested in content than in form, and I have never been a tidy writer. My short stories would sprawl into novels, and one of my novels spread into a trilogy. This book started off as a small history of the jigsaw, but it has spiralled off in other directions,\ and now I am not sure what it is.\ I first thought of writing about jigsaws in the autumn of ????,\ when my young friend Danny Hahn asked me to nominate an icon for a website. This government-sponsored project was collecting English icons to compose a ‘Portrait of England’, at a time when Englishness was the subject of much discussion. At random I chose the jigsaw, and if you click on ‘Drabble’ and ‘jigsaw’ and\ ‘icon’ you can find what I said. I knew little about jigsaws at this point, but soon discovered that they were indeed an English invention as well as a peculiarly English pastime. I then conceived the idea of writing a longer article on the subject, perhaps even a short book. This, I thought, would keep me busy for a while.\ I had recently finished a novel, which I intended to be my last,\ in which I believed myself to have achieved a state of calm and equilibrium. I was pleased with The Sea Lady and at peace with the world. It had been well understood by those whose judgement I most value, and I had said what I wanted to say. I liked the idea of writing something that would take me away from fiction into a primary world of facts and pictures, and I envisaged a brightly coloured illustrated book, glinting temptingly from the shelves of gallery and museum shops amongst the greetings cards, mugs and calendars portraying images from Van Gogh and Monet. It would make a pleasing Christmas present, packed with gems of esoteric information that I would gather, magpie-like, from libraries and toy museums and conversations with strangers. I would become a jigsaw expert. It would fill my time pleasantly, inoffensively. I didn’t think anyone had done it before. I would write a harmless little book that, unlike two of my later novels, would not upset or annoy anybody.\ It didn’t work out like that.\ Not long after I conceived of this project, my husband Michael Holroyd was diagnosed with an advanced form of cancer and we entered a regime of radiotherapy and chemotherapy all too familiarto many of our age. He endured two major operations of hitherto unimagined horror, and our way of life changed. He dealt with this with his usual appearance of detachment and stoicism,\ but as the months went by I felt myself sinking deep into the paranoia and depression from which I thought I had at last, with the help of the sea lady, emerged. I was at the mercy of ill thoughts.\ Some of my usual resources for outwitting them, such as taking long solitary walks in the country, were not easily available. I couldn’t concentrate much on reading, and television bored me,\ though DVDs, rented from a film club recommended by my sister Helen, were a help. We were more or less housebound, as we were told to avoid public places because Michael’s immune system was weak, and I was afraid of poisoning him, for he was restricted to an unlikely diet consisting largely of white fish, white bread and mashed potato. I have always been a nervous cook, unduly conscious of dietary prohibitions and the plain dislikes of others, and the responsibility of providing food for someone in such a delicate state was a torment.\ The jigsaw project came to my rescue. I bought myself a black lacquer table for my study, where I could pass a painless hour or two, assembling little pieces of cardboard into a preordained pattern, and thus regain an illusion of control. But as I sat there, in the large, dark, high-ceilinged London room, in the pool of lamplight,\ I found my thoughts returning to the evenings I used to spend with my aunt when I was a child. Then I started to think of her old age, and the jigsaws we did together when she was in her eighties. Conscious of my own ageing, I began to wonder whether I might weave these memories into a book, as I explored the nature of childhood.\ This was dangerous terrain, and I should have been more wary about entering it, but my resistance was low. I told myself that there was nothing dangerous in my relationship with my aunt, and that my thoughts about her could offend nobody, but this was stupid of me. Any small thing may cause offence. My sister Susan, more widely known as the writer A. S. Byatt, said in an interview somewhere that she was distressed when she found that I had written\ (many decades ago) about a particular teaset that our family possessed, because she had always wanted to use it herself. She felt I had appropriated something that was not mine. And if a teapot may offend, so may an aunt or a jigsaw. Writers are territorial, and they resent intruders.\ I fictionalized my family background in a novel titled The Peppered Moth, which is in part about genetic inheritance. I scrupulously excluded any mention of my two sisters and my brother, and I suspect that, wisely, none of them read it, but I was made conscious of having trespassed. This made me very unhappy. I vowed then that I would not write about family matters again (a constraint which, for a writer of my age, constitutes a considerable loss) but as I sat at my dark table I began to think I could legitimately embark on a more limited project that would include memories of my aunt’s house. These are on the whole happy memories, much happier than the material that became The Peppered Moth. I wanted to rescue them. Thinking about them cheered me up and recovered time past.\ But my new plan posed difficulties. I could not truthfully present myself as an only child (as some writers of memoirs have misleadingly done) and I have had to fall back on a communal childhood ‘we’, which in the following text usually refers to my older sister Susan and my younger sister Helen. My brother Richard is considerably younger than me, and his childhood memories of my aunt are of a later period, although he did spend many holidays with her.\ This book became my occupational therapy, and helped to pass the anxious months. I enjoyed reading about card games, board games and children’s books, and all the ways in which human beings have ingeniously staved off boredom and death and despised one another for doing so. I enjoyed thinking about the nature of childhood and the history of education and play. For an hour or two a day, making a small discovery or an unexpected connection,\ I could escape from myself into a better place.\ I don’t mean in these pages to claim a special relationship with my aunt. My father once said to me, teasingly, ‘Are you such a dutiful niece and daughter because you married into a Jewish family?’\ And I think that the Swifts may have played a part in my relationship with Auntie Phyl. I was captivated by the family of my first husband, Clive Swift. He was the first member of his generation to marry out, but despite this I was made welcome. I loved the Swifts’ strong sense of mutual support and their demonstrative,\ affectionate generosity. They were a powerful antidote to the predominantly dour and depressive Yorkshire Drabbles and Staffordshire Bloors. It was a happy day that introduced me to Clive and the Swifts.\ In The Peppered Moth I wrote brutally about my mother’s depression, and I never wish to enter that terrain again. It is too near, too ready to engulf me as it engulfed her. Some readers have written to me, taking me to task for being hard on my mother,\ but more have written to thank me for expressing their complex feelings about their own mothers. I had hoped that writing about her would make me feel better about her. But it didn’t. It made me feel worse.\ Both my parents were depressive, though they dealt with this in different ways. My father took to gardening and walking with his dog, my mother to Radio 4 and long laments. He was largely silent, though Helen reminds me that he used to hum a lot. My mother could not stop talking. Her telephone calls, during which she complained about him bitterly for hour after hour, seemed never-ending. The last decades of their marriage were not happy,\ but when they were on speaking terms they would do the Times crossword together.\ Doing jigsaws and writing about them has been one of my strategies to defeat melancholy and avoid laments. Boswell regretted that his friend Samuel Johnson did not play draughts after leaving college, ‘for it would have afforded him an innocent soothing relief from the melancholy which distressed him so often’.\ Jigsaws have offered me and many others an innocent soothing relief, and this is where this book began and where it ends.\ Margaret Drabble

The Pattern in the Carpet 1Notes on Quotations 339Acknowledgements 344Bibliography 347

\ Sara SklaroffPart history, part memoir, it is at times frustrating, confounding and even, indeed, puzzling, but I won't make the obvious comparison. She doesn't give us the completionist satisfaction of a jigsaw, for one thing, nor do all the pieces quite fit together in the end. But the book offers readers the pleasing intimacy of following the meanderings of a gifted mind.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyStarred Review. \ Part memoir, part rigorously researched historical perspective, Drabble's book is a multi-layered look at jigsaw puzzles and their role through the ages for society, individuals, and herself; it's also a charming homage to Drabble's beloved Auntie Phyl, who passed her lifelong love of jigsaws on to Drabble. Alongside memories that appear "in bright colours and clear blocks, like the large pieces of a child's wooden jigsaw," Drabble takes a survey of games in literature and art, including Brueghel's 1560 "Children's Games," a complex illustration featuring more than 90 games; and spends much time considering their psychological importance. Readers will probably be surprised, as Drabble was, to learn that jigsaws were originally connected to education rather than amusement; since then, the idea has become one of the "quasi-educational apologia for the doing of jigsaws," the idea that "you learn about the brush strokes of Van Gogh, the clouds of Constable," etc., from puzzling them together. (Indeed, "Doing jigsaws stimulates bizarre theories of art history.") While fascinating, Drabble's highly intellectual, highly British study will pose a special challenge for American audiences. Readers unafraid of doing some extra work will be richly rewarded.\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAn accomplished voice of the British literary world recalls the puzzles that intrigued her in her youth and continue to do so in her maturity. Novelist Drabble (The Sea Lady, 2006, etc.)-who has also edited two editions of The Oxford Companion to English Literature-notes that the best way to attack a jigsaw puzzle is to start at the frame. So she begins with the memory of beloved Auntie Phyl and the village life enjoyed by the author and her family-a pastoral prewar world of tea cozies, morris dancing and biscuit-tin art. Never kitsch, it's pop culture that will be especially attractive to anglophiles. Drabble's rambling discourse in time-"This book started off as a small history of the jigsaw, but it has spiralled off in other directions, and now I'm not sure what it is"-becomes gently illuminating. Starting with a history of jigsaws (notably, didactic "dissected maps") and the story of board games, beginning with the Candyland-like "Royal Game of Goose," the author creates an evocative study in memory and the techniques used to reconstruct it. She eventually ranges through Roman architecture, juvenile literature, mosaics, needlework and the curiosities and crafts of the 18th century. Drabble considers some of her favorite things and curious activities used to ward off melancholy. What starts as a garrulous elder's memoir evolves into an astute miscellany that occasionally wanders but is never lost. A dab hand at fiction and editorship comes through once more, this time with a chockablock memoir fitted under the rubric of pastimes. Agent: Michael Sissons/PFD\ \ \ \ \ Booklist"Drabble's nuanced and revealing jigsaw of vivid memories, little-known facts, and astute observations is both mind-expanding and mood-elevating."\ \ \ \ \ Milwaukee Journal Sentinel"...a fascinating journey...Drabble charms...One of the true pleasures of the book is following Drabble's insatiable curiosity, her scholarly zeal for research and love of knowledge for the sake of knowledge to see where she ends up."\ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewMargaret Drabble readily admits that The Pattern in the Carpet is an eccentric hybrid of a book, a mix of personal memoir and a history of the jigsaw puzzle. When her husband, biographer Michael Holroyd, was fighting advanced cancer, she found she could stave off depression and panic by passing "a painless hour or two, assembling little pieces of cardboard into a preordained pattern, and thus regain an illusion of control." \ So taken was she with the "innocent soothing relief" to be found in jigsaw puzzles that she decided to write a brief history. But, unlike the puzzles themselves, with their tidy borders and preset patterns and the "safety, of knowing that all the pieces will fit together in the end," her book sprawled, growing to address childhood memories and issues of "authenticity and family and folk memory." She writes, "[O]f course I have made things difficult for myself by straying out of my frame and finding new pieces as I go along. This is not the book I meant to write." It may not be the book she meant to write, but it is certain to attract a wider audience than a straightforward history of an activity that many associate with nurseries or nursing homes. A gifted writer can make almost any subject compelling -- think of John McPhee on geology. But puzzles are a real challenge. What kept me reading The Pattern in the Carpet was not Drabble's somewhat rambling, freeform discussion of the interplay between tapestries, mosaics, jigsaws, and board games. Far more interesting are the glimpses of Drabble's early years in East Hardwick and Sheffield, England, in the 1940s, her vivid portrait of her Auntie Phyl, with whom she associates jigsaw puzzles and much that was pleasurable in a childhood marred by depressive parents and her own tendency toward melancholy, and such offbeat personal tidbits as her admission to having "spent as much on dentistry as Martin Amis."\ Part of the allure of puzzles for Drabble is the relief afforded by "hours of freedom from words." Now that she's sworn off fiction because she's afraid of repeating herself, Drabble admits with surprising vehemence to feeling oppressed by writing, which she calls "an illness. A chronic, incurable illness. I caught it by default when I was 21, and I often wish I hadn't. It seemed to start off as therapy, but it became the illness that it set out to cure."\ This, from the author of 17 novels, many centering on women seeking a meaningful balance between family and career, beginning with A Summer Birdcage (1963) and including The Needle's Eye (1972), The Ice Age (1977), The Middle Ground (1980), and The Peppered Moth (2001), her most autobiographical work before this book. Drabble also spent years editing The Oxford Companion to English Literature, a labor that no doubt contributed to her being named a Dame of the British Empire in 2008.\ Drabble emphasizes the contrast between the daunting open-endedness of fiction versus the comforting finiteness of puzzles, which "can't be done badly. Slowly, but not badly. All one needs is patience." In distinction, "The novel is formless and frameless. It has no blueprint, no pattern, no edges. At the end of a day's work on a novel, you may feel that you have achieved something worse than a lack of progress. You may have ruined what went before. You may have sunk into banality or incoherence."\ The Pattern in the Carpet doesn't sink into banality or incoherence, but it does wander where some readers may choose not to follow -- including discussions of changing concepts of childhood, games, and the pastoral, and digressions on three British writers -- John Clare, Alison Uttley, and Robert Southey -- whose names are unlikely to resonate with American readers.\ More interesting are some of the philosophical issues raised by puzzles. Drabble notes that Georges Perec's classic jigsaw novel, La Vie: Mode d'Emploi, "uses the jigsaw as a central metaphor for the tragic futility of human endeavour and the tedium of existence...." She herself wonders intriguingly, "Do I believe in the jigsaw model of the universe, or do I believe in the open ending, the ever evolving and ever undetermined future, the future with pieces that even the physicists cannot number?"\ Jigsaw puzzles were originally educational rather than recreational, first commercialized in the late 18th century by a British bookseller named John Spilsbury, who marketed "dissected maps," which were a learning tool especially popular with royalty. The word jigsaw is a relatively recent coinage, from the late 19th century, derived from the cutting tool also known as the fretsaw -- a word which in my opinion more aptly captures the mounting anxiety that hits as you near completion of a large puzzle and fret that some pieces may be missing.\ Drabble does not mention the disproportionate sense of accomplishment and psychological satisfaction that comes from snapping in the last piece of a puzzle -- the sense of Gestalt -- although puzzles have most definitely been a positive throughout her life.\ This is in large part because of her Auntie Phyl. Phyllis Bloor was her mother's maiden younger sister, a schoolteacher who ran a bread-and-breakfast in Drabble's grandparents' Georgian farmhouse on the Great North Road in Yorkshire. "With my mother, it was nearly impossible to do anything right; with my aunt, it was quite hard to do anything wrong," Drabble writes, revealing -- like Doris Lessing in her memoir Alfred and Emily -- that time doesn't necessarily heal childhood wounds. But jigsaws, Drabble notes, "are a useful antidote to anger."\ After reading The Pattern in the Carpet, I was not struck by an urge to tackle what was touted on a BBC 4 radio program as the World's Most Difficult Puzzle -- the 1964 Springbok edition of Jackson Pollock's Convergence. But I did check out the puzzle offerings in my local stationery store: lots of lighthouses and Impressionist paintings. As Drabble asserts, reassembling a painting that's been fragmented into hundreds of pieces is a great way to become intimate with an artist's strokes. Maybe on my next rainy vacation. --Heller McAlpin\ Heller McAlpin is a New York-based book critic whose reviews appear regularly in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Boston Globe, and Christian Science Monitor, among other publications.\ \ \