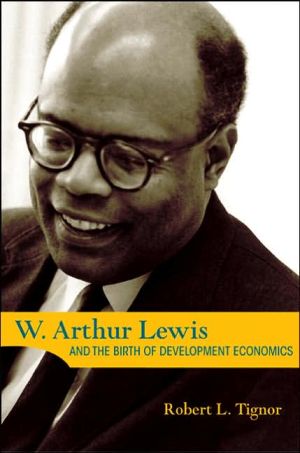

W. Arthur Lewis and the Birth of Development Economics

W. Arthur Lewis was one of the foremost intellectuals, economists, and political activists of the twentieth century. In this book, the first intellectual biography of Lewis, Robert Tignor traces Lewis's life from its beginnings on the small island of St. Lucia to Lewis's arrival at Princeton University in the early 1960s. A chronicle of Lewis's unfailing efforts to promote racial justice and decolonization, it provides a history of development economics as seen through the life of one of its...

Search in google:

"This is a splendid book about a great man. It is full of lessons for all of us as we continue to struggle worldwide with issues of race and of the role of intellectuals as policy advisors. Few human beings have ever had the intelligence, the courage, and the grace of Arthur Lewis; for that reason, Arthur's disappointments in trying to improve life in Ghana and the West Indies are sobering indeed."--William G. Bowen, President Emeritus, Princeton University, and President, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation"Robert Tignor's book tells the story of a fascinating man in fascinating times. It is a story that gets the reader into one of the most important dramas of the past half century: the attempt to build free and prosperous nations out of impoverished colonies."--Fred Cooper, New York University"More than a mere biography of this remarkable man, this book is an eminently readable study of several important matters. It lays out the origins of development theory as a significant branch of economic analysis. It helps us to understand why so many developing countries have failed to make economic progress. It offers insights into the structure of racial discrimination. And it tells the fascinating story of a very wise man and his role inside and outside the academy."--William Baumol, New York University"Bob Tignor's fine intellectual biography of his friend Sir Arthur Lewis, traces the development of one of the most important and enigmatic economists of the twentieth century. Tignor's book has much to tell us about the brutal conflict between development economics and politics in post-colonial Africa, a conflict that still casts its shadow over the least-developed continent of the world."--Angus Deaton, Princeton University"Tignor provides an exciting epic of economist-as-engaged-public-figure. His many gifts as a historian are especially evident in the multi-faceted and definitive accounts of Lewis's role as principled United Nations advisor and as a fighter for supranational Caribbean institutions."--Mark Gersovitz, The Johns Hopkins UniversityAlfred E. Eckes - International History ReviewIn this splendid intellectual biography, Robert L. Tignor examines Lewis's career and thought, giving particular emphasis to his experiences in Africa. . . . This is an important biography, and one that will benefit scholars seeking to understand the enormous gap between economic aspirations and achievements in much of the developing world, as well as the struggle for racial justice. For students of post-independence Africa the book has special relevance.

W. Arthur Lewis and the Birth of Development Economics\ \ By Robert L. Tignor \ Princeton University Press\ Copyright © 2005 Princeton University Press\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-691-12141-3 \ \ \ Introduction\ WORLD WAR II SET IN MOTION radical changes around the globe, many of which W. Arthur Lewis, the subject of this study, favored and sought to accelerate. Radiating outwards from the bloody battlefields of the Soviet Union and Western Europe, the war spread its social disruption, its maiming of civilian and military populations, and its waves of death and destruction into East and Southeast Asia. Although the war began in Europe, it quickly drew Asia, Africa, and the Americas into its orbit. Large contingents of Indian, African, and West Indian soldiers were ferried across the seas and fought alongside European and North American forces. Moreover, winning this modern war entailed more than having larger, better-equipped, and better-led military forces. Victory required well-educated and loyal civilian populations, lending their intellect and their belief in the allied cause to the bravery of their military colleagues. Here, too, the contributions of civilian populations from around the globe were desperately needed. Africans, West Indians, and Indians rose to the challenge, mostly enthusiastically, to repulse the destructive ideologies and war ambitions of German Nazism and Italian and Japanese Fascism. \ By war's end,new configurations of power and new attitudes toward race and wealth had come to the fore. India was the first of the imperial territories to gain independence from Europe's mighty empires after the war. Race relations were being reexamined and altered. In South Africa a Nationalist Party, seeking to resist the wind of change blowing through the world's polities, erected a system of racial separation through apartheid. Elsewhere, partly because the peoples of the world had worked together to defeat the Axis powers, political leaders rewrote racial legislation and promoted racial mixing. President Harry Truman integrated the American armed services in this period. Concerns about wealth and poverty and the distribution of income within countries and between countries, which had not been addressed during the war years, now emerged as burning political issues in all of the world's countries.\ Three considerations that surfaced so forcefully in the aftermath of the war-decolonization, race relations, and economic growth-were preeminent issues in the life of W. Arthur Lewis. As a person of color who grew up in an impoverished and largely ignored corner of the British Empire, he devoted much of his academic career and public life to elucidating these matters and promoting a vision of a decolonized, color-blind, and prosperous community of independent nations. From the moment he arrived to take up his studies in Great Britain, he sought out Fabian socialists in order to share with them his understanding of the oppressive colonial forces that had led West Indian populations to riot against their colonial rulers in the 1930s. Despite many disagreements with the British Colonial Office, he joined with its officials to combat fascism and to draw up plans for a changed relationship between Britain and its colonies once the war had concluded. Physically unable to serve in the British armed forces, a graduate of the prestigious London School of Economics, and one of that institution's most accomplished young economists, Lewis soon became a fixture at the British Colonial Office. Even as it seemed that military victory was still far removed, officials in the Colonial Office set about preparing for a world that they recognized would be radically different from the colonial world over which the British had held sway before 1939. Lewis threw himself into the task of advising the Colonial Office with an enthusiasm surely intensified by the fact that he expected the postwar world to be more egalitarian, less racist, and less imperialist than the prewar had been.\ World War II brought W. Arthur Lewis to the attention of members of Britain's ruling class. Even before 1939, however, he had already impressed his teachers at the London School of Economics with the perspicacity of his economic reasoning and the elegance of his ideas, which he was able to express with uncommon clarity and irrefutable logic. Although the LSE had never had a faculty member who was of African descent, Lewis's performance in class and on his thesis persuaded them that he was just the person to break the color barrier at their institution. Such was to be the pattern throughout his life. The first person of African descent to hold a named chair at a British university (Manchester), he went on to become the chief economic adviser to Ghana, tropical Africa's first country to gain its independence from European rulers after World War II. He followed this stint in Ghana by becoming the first black principal of the University College of the West Indies, the first vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, and in 1963 the first black professor at Princeton University. Not surprisingly, he was also the first economist of African descent to win the Nobel Prize in economics, an award presented to him in 1979.\ Lewis, then, was an extraordinary man in his own right, well deserving of an intellectual biography. His contributions to the field of development economics were significant and pioneering and made him the founding figure of a wholly new branch of economics in the 1950s. His 1954 article on economic development using unlimited supplies of labor, published in Manchester School, was arguably the single most influential essay in this field. It was certainly one of the most frequently cited essays of the late 1950s and early 1960s. His activities with the British Colonial Office, the United Nations, the World Bank, the government of Ghana, and the University of the West Indies gave him a public presence attained by few scholars. This combination of scholarly and public factors, so movingly encapsulated in his personal papers, makes his life a prism for viewing some of the preeminent preoccupations of the mid-twentieth century. The narrative of Lewis's life provides an observer with a privileged place from which to view people of color entering the imperial center as students and pursuing careers in professions like economics where specialized training provided access to power. Lewis experienced race relations during an era when civil rights were coming to the fore; he wrote on the methods for promoting economic development when economic growth was on everyone's lips; and he held important public positions in Africa's first decolonized state, Ghana, and in the West Indies as those colonial islands seemed on the pathway to an independent political federation.\ According to the historian Daniel Halévy, war is a potent accelerator of historical trends. Nothing could be more true of World War II. In its wake, and far more quickly than any of the principals anticipated, white and black, colonizer and colonized, rich and poor were caught up in debates and disputes over racial justice, political independence, economic growth, and the redistribution of wealth. Under pressure from peoples of color, colonial populations, and the better-organized segments of the less fortunate part of the world's populations, ruling groups bent to these demands by altering civil codes, amending racial laws, and taking an interest in global economic development. W. Arthur Lewis was deeply involved in all of these changes. In the early part of his career, as a student and young lecturer at the London School of Economics, he came face to face with British racial discrimination. As a young man still in his twenties, he fought to open Britain's leading government institutions, notably the armed forces and the Colonial Office, to nonwhite British subjects like himself. He led British-based, West Indian delegations of the League of Coloured Peoples to the Colonial Office, demanding that the British government make its institutions accessible to all qualified candidates, not just those born of European parents. As part of this campaign, Lewis devoted a full issue of the League's publication, The Keys, to exposing the racism and hypocrisy of the British ruling classes who were calling on the empire to rally behind the war against Fascism and were pointing up the vulgar racism of the Fascist ideology, while at the same time refusing to enroll well-qualified persons of color in the officer corps of the armed forces or in high-level Colonial Office postings.\ As the war drew to a close, Lewis turned his attention to the nationalist movements that were bursting forth around the world, especially in Africa and the Caribbean, and that were destined to culminate in decolonization settlements. Lewis worked with nationalists in the Gold Coast before independence, celebrated their triumphal moment of political independence in March 1957, and then left the comfort of his prestigious academic position as a chaired professor of political economy at the University of Manchester to become Ghana's chief economic adviser and the individual charged with the responsibility for guiding the country's economic programs. Ghana seemed an ideal setting to implement formulas for economic growth. Not only did the country have a sound infrastructure and a relatively high standard of living, but its charismatic leader, Kwame Nkrumah, whom Lewis knew and admired and of whose leadership he expected great things, seemed to embody just the right mix of idealism, talent, and savvy to lead his people to political and economic successes.\ Ghana proved disappointing. Nkrumah frustrated Lewis by blocking the economic adviser's initiatives. Before long, Lewis found himself sidelined and believed that he had no alternative but to leave Ghana before being compelled to resign in a public dispute that he believed would endanger other decolonizing efforts in Africa.\ Departing Ghana, he went back to his homeland, the West Indies, to which he had always intended to return. Here, too, as principal of the University College of the West Indies and then vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies, he seemed to be ideally situated to blend academics and public involvement. In his writings on economic development, Lewis always underscored the importance of education for economic development. Human resource development was to his way of thinking the key to economic development. What better opportunity could he have to foster the economic growth of his home territory than to serve as the head of the area's leading institution of higher learning? In addition, the British West Indies seemed on the verge of becoming an independent political federation, a goal that Lewis had championed since his youthful days and that he knew would buttress the mission and strength of the University of the West Indies. Nonetheless, in the West Indies, as in Ghana, Lewis struggled mightily, but with disappointing results. He kept the university from disintegrating even while the West Indian political federation failed. The effort left him exhausted and ready to take up a more serene academic position in the United States.\ Racial justice and economic progress were Lewis's passions. Yet he was, at heart, an intellectual and a scholar. He spoke often of his distaste of politics. The compromises that politicians had to make to achieve their goals dismayed him. He thrived at Princeton, publishing prolifically and receiving countless invitations to offer advice to important government agencies. Yet here, too, he was drawn into swirling controversies over the place of race in higher education. His critical comments about the black power movement and its influence on young minds left some intellectuals deeply dismayed, though, in truth, they stemmed from long-held and well-thought-out perspectives on the way forward for people of color in predominantly white societies.\ Although Lewis was fond of saying that he became an economist by accident, because the occupations of engineering, colonial service, and business were closed to him, it is hard to imagine that he would not have gravitated to a field so well suited to his personality and way of thinking. His was a precise mind. He was truly a child of the Enlightenment, as he liked to say, for he believed that men and women through hard study could understand the universe in which they lived and divine the laws that would lead to human betterment. It was this energy that led him to the scholarly breakthroughs in the mid-1950s, notably the article on unlimited supplies of labor and the treatise on economic growth, and again in the 1980s when he wrote about the history of economic development. These were his most important scholarly achievements. They were foundational works in the emerging field of development economics and economic history, and they made their way into the curriculum of universities. And because they were written by a man of color from the colonial world, they catapulted Lewis to the top rank of consultants, in high demand from Western governments, like Britain and the United States, as well as decolonized territories, like Ghana.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from W. Arthur Lewis and the Birth of Development Economics by Robert L. Tignor Copyright © 2005 by Princeton University Press. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

List of Illustrations vii Preface ix INTORDUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Getting Started: Education and Race 6 CHAPTER 2: The Colonial Office 42 CHAPTER 3: Unlimited Supplies of Labor 79 CHAPTER 4: The Gold Coast 109 CHAPTER 5: Ghana's Chief Economic Adviser, 1957-58 144 CHAPTER 6: Ghana: Part 2 179 CHAPTER 7: The West Indies, 1959-63 212 CHAPTER 8: The Princeton Years, 1963--91 240 CONCLUSION 268 Bibliography 279 Index 303

\ Times Higher Education Supplement - Lawrence Haddad\ Tignor's book is one for enthusiasts of development, of social science research and of African history. It is long, closely written, tightly researched and scrupulously comprehensive.\ \ \ \ \ Business History Review - Ranald Michie\ This book can be read on two levels. On the human level, it is the story of triumph against adversity. . . . [A]t the level of the contribution made by a professional economist to economic development, this book reads as a story of intellectual failure in the face of political reality. . . . Each of these chapters is thoroughly researched, judiciously blending discussions of Lewis's personal life and of the changes taking place in the world.\ \ \ International History ReviewIn this splendid intellectual biography, Robert L. Tignor examines Lewis's career and thought, giving particular emphasis to his experiences in Africa. . . . This is an important biography, and one that will benefit scholars seeking to understand the enormous gap between economic aspirations and achievements in much of the developing world, as well as the struggle for racial justice. For students of post-independence Africa the book has special relevance.\ \ \ \ \ Journal of African American HistoryRobert Tignor has produced an impressive intellectual biography of the remarkable economist, policy advisor, and educator, Sir W. Arthur Lewis.\ \ \ \ \ Times Higher Education SupplementTignor's book is one for enthusiasts of development, of social science research and of African history. It is long, closely written, tightly researched and scrupulously comprehensive.\ — Lawrence Haddad\ \ \ \ \ Business History ReviewThis book can be read on two levels. On the human level, it is the story of triumph against adversity. . . . [A]t the level of the contribution made by a professional economist to economic development, this book reads as a story of intellectual failure in the face of political reality. . . . Each of these chapters is thoroughly researched, judiciously blending discussions of Lewis's personal life and of the changes taking place in the world.\ — Ranald Michie\ \ \ \ \ International History ReviewIn this splendid intellectual biography, Robert L. Tignor examines Lewis's career and thought, giving particular emphasis to his experiences in Africa. . . . This is an important biography, and one that will benefit scholars seeking to understand the enormous gap between economic aspirations and achievements in much of the developing world, as well as the struggle for racial justice. For students of post-independence Africa the book has special relevance.\ — Alfred E. Eckes\ \ \ \ \ Journal of African American HistoryRobert Tignor has produced an impressive intellectual biography of the remarkable economist, policy advisor, and educator, Sir W. Arthur Lewis.\ — James B. Stewart\ \