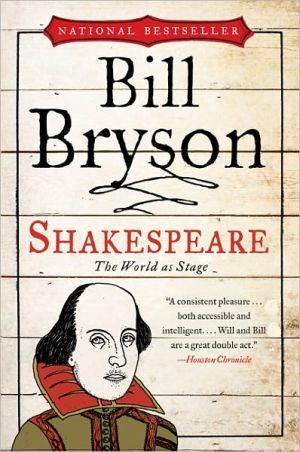

Year in the Life of William Shakespeare 1599

1599 was an epochal year for Shakespeare and England\ \ Shakespeare wrote four of his most famous plays: Henry the Fifth, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and, most remarkably, Hamlet; Elizabethans sent off an army to crush an Irish rebellion, weathered an Armada threat from Spain, gambled on a fledgling East India Company, and waited to see who would succeed their aging and childless queen.\ James Shapiro illuminates both Shakespeare’s staggering achievement and what Elizabethans experienced...

Search in google:

Unlike any other book on Shakespeare, this one takes a single year and from the events of twelve months illuminates the whole of William Shakespeare's life and writing career. During 1599, Shakespeare wrote four great plays: HENRY V, JULIUS CAESAR, AS YOU LIKE IT, and HAMLET. In each of those plays, he made a significant dramatic advance, staked out new territory even for a writer who was as inventive as he was. He also supervised the building of the new Globe Theater, settled into living in London (while his family stayed in Stratford) and shared with his countrymen the extraordinary events of this year: an English invasion of Ireland, the terrifying threat of a Spanish invasion, and the creation of the famed East India Company. It was a volatile period and the plays mirror England's role in global history, while Shakespeare's genius advances by leaps and bounds. on A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare - Financial Times "Still more are on the way, of which James Shapiro's...will be among the most original."

A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare\ 1599 \ \ By James Shapiro \ HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.\ Copyright © 2005 James Shapiro\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0060088737 \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ A Battle of Wills\ \ Late in the afternoon of Tuesday, December 26, 1598, two days before their fateful rendezvous at the Theatre, the Chamberlain's Men made their way through London's dark and chilly streets to Whitehall Palace to perform for the queen. Elizabeth had returned to Whitehall in mid-November in time for her Accession Day celebrations. Whitehall, her only London residence, was also her favorite palace, and she spent a quarter of her reign there, especially around Christmas. Elizabeth's entrance followed traditional protocol: a mile out of town she was received by Lord Mayor Stephen Soame and his brethren, who were dressed in "velvet coats and chains of gold." Elizabeth had come from Richmond Palace, where she had stayed but a month, having been at her palace at Nonsuch before that. Sanitation issues, the difficulties of feeding so many courtiers with limited local supplies, and perhaps restlessness, too, made the Elizabethan court resemble a large-scale touring company that annually wound its way through the royal palaces of Whitehall, Greenwich, Richmond, St. James, Hampton Court, Windsor, Oatlands, and Nonsuch. But in contrast with the single cart that transported an itinerant playing troupe with its props and costumes, a train of several hundred wagons would set off for the next royal residence, transporting all that was needed for the queen and seven hundred or so of her retainers to manage administrative and ceremonial affairs at a new locale.\ A century later Whitehall would burn to the ground, leaving "nothing but walls and ruins." Archaeological reconstruction would be pointless, for Whitehall was more than just a jumble of Gothic buildings already out of fashion by Shakespeare's day. It was the epicenter of English power, beginning with the queen and radiating out through her privy councillors and lesser courtiers. A cross between ancient Rome's Senate and Coliseum, Whitehall was where ambassadors were entertained, bears baited, domestic and foreign policy determined, lucrative monopolies dispensed, Accession Day tilts run, and Shrovetide sermons preached. Above all, it was a rumor mill, where each royal gesture was endlessly dissected. When the Chamberlain's Men performed at court, they added one more layer of spectacle.\ Whitehall figured strongly enough in Shakespeare's imagination to make a cameo appearance in his late play Henry the Eighth. When a minor courtier describes how after her coronation at Westminster Anne Bullen returned to "York Place," he is sharply corrected: "You must no more call it York Place; that's past, / For since the Cardinal fell, that title's lost." Henry VIII coveted the fine building, evicted Cardinal Wolsey, and rechristened it: " 'Tis now the King's, and called Whitehall." The courtier who so carelessly spoke of "York Place" apologetically explains that "I know it, / But 'tis so lately altered that the old name / Is fresh about me" (4.1.95-99). Whitehall's identity was subject to royal whim, its history easily rewritten. That this exchange follows a hushed discussion of "falling stars" at court makes its political edge that much sharper.\ For a writer like Shakespeare, whose plays exhibit a greater fascination with courts than those of any other Elizabethan playwright, visits to Whitehall were inspiring. The palace was a far cry from anything he had ever experienced in his native Stratford-upon-Avon, which extant wills and town records portray as a drab backwater, devoid of high culture. There was little touring theater, few books, hardly any musical instruments, no paintings to speak of, the aesthetic monotony broken only by painted cloths that adorned interiors (like the eight that had hung in Shakespeare's mother's home in Wilmcote). It had not always been this way. Vivid medieval paintings of the Passion and the Last Judgment had once decorated the walls of Stratford's church, but they had been whitewashed by Protestant reformers shortly before Shakespeare was born.\ Whitehall had everything Stratford lacked. It housed the greatest collection of international art in the realm, its "spacious rooms" hung "with Persian looms," its treasures "fetched from the richest cities of proud Spain" and beyond. For an Englishman who (like his queen) had never left England's shores, it offered a rare opportunity to see work produced by foreign artisans. A short detour up a staircase into the privy gallery overlooking the tiltyard led Shakespeare into a breathtaking gallery. Its ceiling was covered in gold, and its walls were lined with extraordinary paintings, including a portrait of Moses said to be "a striking likeness." Near it hung a "most beautifully painted picture on glass showing thirty-six incidents of Christ's Passion." But the most eye-catching painting in the passageway was the portrait of young Edward VI. Those approaching it for the first time found that "the head, face and nose appear so long and misformed that they do not seem to represent a human being." Installed on the right side of the painting was an iron bar with a plate attached to it. Visitors were encouraged to extend the bar and view the portrait hrough a small hole or "O" cut in the plate: to their surprise, "the ugly face changed into a well-formed one."\ A few years earlier this famous picture had inspired Shakespeare's lines about point of view in Richard the Second: "Like perspectives, which rightly gazed upon / Show nothing but confusion, eyed awry / Distinguish form" (2.2.18-20). It may also have inspired a similar reflection in Henry the Fifth about seeing "perspectively" (5.2.321). What the Chorus in this play calls the "Wooden O," the theater itself, operates much like this Whitehall portrait: its lens is capable of giving shape and meaning to the world, but only if playgoers make the necessary imaginative effort.\ Leaving this picture gallery, Shakespeare would next have entered the long privy gallery range that led past the Privy Council chamber, where Elizabeth's will was translated into government policy. The Christmas holiday had not disrupted the councillors' labors; seven of them had met there that day, ordering, among other things, that warm clothing be secured for miserably equipped English troops facing a bitter Irish winter. The councillors adjourned in time for that evening's entertainment and resumed their deliberations the following morning.\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare by James Shapiro Copyright © 2005 by James Shapiro.\ Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ From Barnes & NobleInstead of a full-scale Shakespeare biography, Columbia University professor James Shapiro offers us a brilliant micro-history, a slice of the Stratford Bard's life. He centers his narrative on 1599, a year crucial not only to the dramatist's artistic evolution but also to England's national destiny. He places Henry VI, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and Hamlet within the context of their times, most especially to upheavals in Elizabeth's court and the threatened second assault by the Spanish Armada. He doesn't neglect events closer to the London stage; including the construction of the Globe and the retirement of comic actor Will Kemp. A stimulating study.\ \ \ \ \ Booklist (starred review)“This book is a masterpiece, simply a masterpiece.”\ \ \ The Economist"James Shapiro throws an unusually searching light across Shakespeare’s creative genius and makes him come truly alive."\ \ \ \ \ Booklist"This book is a masterpiece, simply a masterpiece."\ \ \ \ \ William E. Cain"Very distinguished...captivating...Shapiro succeeds where others have fallen short."\ \ \ \ \ Alexandra Alter"Only an extraordinary scholar could illuminate Shakespeare’s singular genius by demonstrating how much his work owes to Elizabethan cultureandsociety."\ \ \ \ \ Peter Kemp"Superb—the product of marathon scholarship, inspired insight, narrative flair, astute surmise and searching intelligence."\ \ \ \ \ Robert McCrum"an unforgettable illumination of a crucial moment in the life of our greatest writer."\ \ \ \ \ Jonathan Bate"[This] is one of the few genuinely original biographies of Shakespeare."\ \ \ \ \ Nicholas Hytner"a brilliantly readable and revealing narrative."\ \ \ \ \ Fintan O'Toole"For Irish readers...by far the best account yet written of the relationship between this island and Shakespeare’s work."\ \ \ \ \ Jeremy Treglown"If Will in the World is essentially an extremely good historical novel, [YLOWS] is history itself"\ \ \ \ \ Sam Leith"Excellent book....superbly illuminating....Shapiro deserves whoops of applause."\ \ \ \ \ Francis Wilson"Shapiro gives us a Shakespeare who chronicles his age, in a biographical form that speaks clearly to our own."\ \ \ \ \ Andrew Motion"Quite brilliant….It gives a whole large picture of his life, times, and achievement. Wonderful."\ \ \ \ \ Sir"As a yarn, this is up there with The Da Vinci Code but in 1599 it’s all true!"\ \ \ \ \ Jacques Barzun"Mr. Shapiro has given us by his encyclopedic scholarship and lucid narrative a hitherto unknown Shakespeare."\ \ \ \ \ Stanley Wells"[P]assionately written study, the product of deep scholarship and acute critical thought... fascinating."\ \ \ \ \ Christopher Rush"a stunning exhibition of scholarly intelligence by an academic deeply committed to arriving at the truth."\ \ \ \ \ David Lister"deliciously vivid....Shapiro weaves a tantalising narrative."\ \ \ \ \ David Scott Kastan"Shapiro’s scrupulous scholarship has given us a Shakespeare both for his time and our own."\ \ \ \ \ The Economist“James Shapiro throws an unusually searching light across Shakespeare’s creative genius and makes him come truly alive.”\ \ \ \ \ John SimonShapiro does a fine job showing how this historic change gave birth to "Hamlet," with its inwardness and psychologizing, and to the row of great tragedies that followed.\ — The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Financial Times"Still more are on the way, of which James Shapiro's...will be among the most original."\ —on A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare\ \ \ \ \ The Spectator"Excellent book....superbly illuminating....Shapiro deserves whoops of applause."\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe year 1599 was crucial in the Bard's artistic evolution as well as in the historical upheavals he lived through. That year's output-Henry V, Julius Caesar, As You Like It and (debatably) Hamlet-not only spans a shift in artistic direction and theatrical taste, but also echoes the intrigues of Queen Elizabeth's court and the downfall of her favorite, the Earl of Essex. Like other Shakespeare biographers, Columbia professor Shapiro notes the importance of mundane events in Shakespeare's art, starting here with the construction of the Globe Theatre and the departure of Will Kemp, the company's popular comic actor. Having a stable venue and repertory gave Shakespeare the space to write and experiment during the turmoil created by Essex's unsuccessful military ventures in Ireland, a threatened invasion by a second Spanish Armada and, finally, Essex's disastrous return to court. Shapiro is in a minority in arguing for Shakespeare initially composing Hamlet at the same time Essex was plotting a coup; there's little textual or documentary evidence for that dating. Still, Shapiro's shrewd discussion of what is arguably Shakespeare's greatest play, particularly its multiple versions, rounds out this accessible yet erudite work. 8 pages of color illus., 22 b&w illus. not seen by PW. Agent, Anne Edelstein. (Oct. 18) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Children's LiteratureWhile William Shakespeare is perhaps one of the most famous writers ever to have lived, little is known about his life. Even less known is the fact that Shakespeare wrote four of his most famous plays--Henry the Fifth, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and Hamlet--all in one remarkable year. James Shapiro takes a detailed look at what was going on in England as well as with Shakespeare's own life, and how those events shaped not only the plays, but their popularity with audiences at the time. The book is divided into four sections, one for each season of 1599. Each section explains the English political climate and how it affected audience reaction to the plays (for example, Julius Caesar was written during a time when numerous attempts upon Queen Elizabeth's life were made). Also, major events that would have affected Shakespeare as an artist (such as the raising of Globe Theater in London and the death of the famous poet Edmund Spenser) are chronicled. Personal details in Shakespeare's life (the few that have not been lost to time, that is) are also explained and speculated about, such as what Shakespeare's homecoming after a long absence may have been like. While the book is a bit weighty for the young adult reader, it does help relate Shakespeare's plays to the real world. 2005, HarperCollins, Ages 14 up. \ —Amie Rose Rotruck\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis book is not your typical biography. Shapiro (English & comparative literature, Columbia Univ.; Shakespeare and the Jews) offers a critical examination of four plays Shakespeare wrote in the seminal year of 1599-Henry V, Julius Caesar, As You Like It, and Hamlet-and of the events that influenced the Bard at the time of their writing. As Shapiro critically evaluates the plays, he indicates how Shakespeare developed as a writer and how he used the events of the year, such as the English invasion of Ireland and increased government censorship, to shape and influence his plays. Unlike recent biographies of the Bard, this work gives the reader a realistic sense of the multilayered and complex political, social, and literary pressures that influenced Shakespeare as a citizen of England, as a business partner in the Globe Theatre, and as a writer. Also included are bibliographic essays for each chapter. Recommended for public libraries with an interest in Shakespeare and for academic libraries. [See Prepub Alert, LJ 7/05.]-Shana C. Fair, Ohio Univ. Lib., Zanesville Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAn intriguing addition to Shakespeare studies, stressing his immersion in the issues of his time. Shapiro (English/Columbia Univ.) identifies 1599, when Shakespeare and his fellow shareholders built the Globe Theatre, as the pivotal year during which the 35-year-old playwright's style changed and his ambitions grew as he wrote four new plays. He had already established a strong reputation with successful comedies and histories like A Midsummer Night's Dream and Henry IV, but Shapiro contends that Shakespeare "was restless, unsatisfied with the profitably formulaic." The departure from the Chamberlain's Men of Will Kemp, the great comic who played Falstaff, signaled the playwright's break with an older form of theater rooted in folk traditions. Falstaff was gone from Henry V, a drama poised on the knife's edge between patriotism and cynicism that reflected contemporary spectators' mixed feelings about an unpopular Irish war; fears of a Catholic plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth fueled the Roman characters' debates in Julius Caesar. With As You Like It, the Bard moved toward a mature view of love quite unlike his earlier "honey-tongued" romantic poetry. This productive year closed with Shakespeare drafting Hamlet, which transformed the monologue by using it to convey the interior workings of a character's mind. Shapiro's best chapters cogently analyze Shakespeare's extensive revisions of Hamlet, which backed away from the first draft's radical break with theatrical tradition and softened its dark, existential tone just enough to avoid alienating his audience. The book's early sections, heavy on specific incidents in Elizabethan history, will not be to everyone's taste, but they'renecessary to the author's detailed and ultimately convincing argument that to appreciate Shakespeare as a genius for all ages, we must understand how his art addressed the concerns of his own. Sure to be hated by Harold Bloom and others who view any attempt to locate the Bard in history as blasphemy against the religion of Pure Art, but open-minded readers will be stimulated and enriched by Shapiro's contextual approach.\ \